Celebrating Black History Month: 10 Women You Should Know

Happy Black History Month!

In the course of Season 1 on 19th-century America, we met some truly incredible women. In a time when women of color had few rights and very little encouragement to try and claim any, these women defied all odds to do some pretty impressive things.

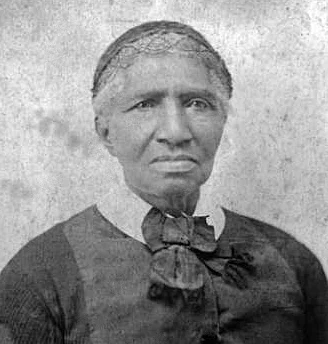

1. the eloquent speaker:

Sojourner Truth

Courtesy of the Library of Congress

Sojourner Truth was born into slavery in New York, but escaped in 1826. Her terrible owner had promised her freedom if she was well behaved, but when he didn’t follow through on the date they’d agreed on, she walked off. He was not happy. “I did not run off,” she said later, “for I thought that wicked, but I walked off, believing that to be all right.” She later sued her old owner to try and get legal custody of her children…remember this is LONG before emancipation came around. She devoted her life to helping others: fighting for abolition, helping to recruit black troops for the Union Army, advocating for prison reform, and for women’s suffrage to boot (in a time when most suffragettes were most certainly both white and very privileged). This was not an easy age to be a female public speaker, let alone a black woman. In May 1851, she delivered an improvised speech at the Ohio Women's Rights Convention in Akron that would become her famous "Ain't I A Woman?" even though she was very well spoken and NEVER spoke like that (to see the two versions side by side, check this out).

“I have heard much about the sexes being equal; I can carry as much as any man, and can eat as much too, if I can get it. I am as strong as any man that is now. As for intellect, all I can say is, if women have a pint and man a quart - why can’t she have her little pint full?”

There are many ways to learn more on Sojourner, but for a full and delightful picture, listen to the History Chicks’s episode on her.

2. the rebel with a mighty cause:

Harriet Tubman

Courtesy of the Library of Congress

Harriet is one of the most consummate badasses history has ever seen. After escaping - on foot, by herself - from enslavement in Maryland in 1849, Harriet turned right around and started smuggling people out of bondage as a conductor on the Underground Railroad. She was one of the only, if not THE only, African American female conductors. Over the course of a decade, she rescued most of her family members and many others, managing to do the almost unthinkable: she never got caught.

“I was the conductor of the Underground Railroad for eight years, and I can say what most conductors can’t say — I never ran my train off the track and I never lost a passenger.”

She went on to become a Civil War nurse, and then a spy, helping to plan and execute one of the Union’s most successful raids in enemy territory. She spent the rest of her life fighting for African American rights and women’s suffrage, and she opened a home for the poor and indigent.

To find out more about Harriet, and about the lives of women in slavery, listen to/read episodes 9 and 10.

3. the tenacious dressmaker:

Elizabeth Keckley

Wikicommons

We should all know this woman’s name. Born into slavery in Virginia, Lizzie had a predictably difficult childhood and first 30 years of life. Though she was the daughter of her white owner, she wasn’t given any special treatment. She was subjected to backbreaking work, beatings, and humiliation. She was assaulted for years by a white neighbor, who was never punished. But she held onto her sense of worth and never gave up the fight for a better life.

“I told him that I was ready to die, but that he could not conquer me. ”

Her mom taught her a crucial skill: sewing. She turned that skill into a thriving dressmaking business, eventually buying her own freedom because of how very good at it she was. This is the ultimate rags to riches story: she moved to Washington D.C., where she became one of the most successful dressmakers around, catering to the rich and famous with her poise and her incredible style. She became First Lady Mary Lincoln’s #1 dressmaker and friend, getting a behind-the-scenes seat in the White House for the entirety of the Civil War. During that time, she started and became president of an organization that raised money for the African Americans she saw pouring into the city, without a job or a penny to their name.

To find out more about Lizzie, and about the lives of women in slavery, listen to/read episodes 9 and 10.

4. the philanthropist angel of colorado:

Clara Brown

Wikicommons

We often think of white guys in big hats when we think about the Wild West, but Clara Brown is the ultimate embodiment of frontier grit and spirit. Born into slavery in Virginia, Clara Brown talked her way onto a wagon train headed West by promising to be the prospector’s cook and laundress. She walked most of the 700 miles. In Denver, she made a boatload of money as a professional laundress to the city’s many dirty and domestically hopeless gentlemen, then wisely invested it in local businesses and real estate. This woman lovingly called “Aunt Clara” became one of the richest people in town, turning her house into a hospital and home for the lost and impoverished. After the Civil War, she used some of her money to search for her husband and kids, who had all been sold away from her. She didn’t find them, but still managed to bring 26 formerly enslaved people back to Colorado and helped them find jobs and places to live. Clara was in her 70s when she was finally reunited with one of her daughters. She was one of the first and most beloved black philanthropists of the West.

To find out more about pioneering women of the West, check out episode 11.

5. the trailblazer:

Elizabeth Key Grinstead

Wikicommons

In 1630, Elizabeth Key was born to an African woman and a white man named Thomas Key. He was married already, but eventually he was forced to take responsibility for her, and she was considered an indentured servant until she got old enough to support herself. But here’s the rub: her father died, and her indenture was passed on to other dudes who conveniently forgot that she was supposed to be freed by 1645. In 1650, she met a white indenture named William Grinstead and had a child with him. They couldn’t marry, as Grinstead hadn’t served his indenture yet, and suddenly those slippery suckers were saying that she AND her child were considered slaves. But Elizabeth was having none of it. In 1656 in Virginia, not much more than a decade or so after the first African slaves arrived, she fought her way up the legal chain and sued for her freedom based on who her father was – a white Englishman. And guess what? She won, becoming one of the first women in the colonies to do so.

To find out more about Elizabeth, check out the Global Women’s History Blog.

6. the teacher, nurse, and author:

Susie King Taylor

Wikicommons

In 1850s Savannah, Georgia, a young woman named Susie Baker openly defied harsh laws that said she wasn’t allowed to learn to read by attending secret schools run by black women and seeking out help from two white teens. Just so you know, those defying such laws were punished a la The Handmaid’s Tale. Seriously: think about that next time you pick up a book in your leisure time. When the war broke out, she fled to St. Simon’s Island, where she was asked to put her education to work by organizing a school, becoming the first black teacher at a freed person’s school in Georgia.

“My people are striving to attain the full standard of all other races born free in the sight of God, and in a number of instances have succeeded. Justice we ask, to be citizens of these United States, where so many of our people have shed their blood with their white comrades, that the stars and stripes should never be polluted.”

She later married Edward King and followed him and the 33rd United States Colored Troops as nurse, teacher and laundress. For several years, this formerly enslaved woman took care of these soldiers, teaching many how to read and write in their down time. She was never paid for her work. She went on to write a memoir called My Life in Camp with the 33d United States Colored Troops, Late 1st S.C. Volunteers, becoming the only black woman to write about her wartime experiences.

To find out more about what Civil War nurses had to put up with, tune in to/read episode 2.

7. the undercover soldier:

Cathay Williams

Wikicommons

Women were soldiers in the Civil War, too - and Cathay had to be one of the toughest. After fighting and being injured several times under the name William Cathey, Cathay Williams became the only documented female Buffalo Soldier: that's the first African American peacetime army regiment, known for their stinky buffalo coats and their utter hardcoredness. She felt a bit hard done by, though. “The men all wanted to get rid of me after they found out I was a woman,” she said. “Some of them acted real bad to me.” Like many lady soldiers, her pension request is later denied.

To find out more about secret lady Civil War soldiers (including several black women, one of whom GAVE BIRTH IN THE FIELD) check out episode 5. For more on women in the west, listen to/read episode 11.

8. the hardcore spy:

Mary Bowser

Wikicommons

During the Civil War - in Richmond, the heart of the Confederacy - a Union sympathizer named Elizabeth Van Lew offers Confederate First Lady Varina Davis her slave as a house servant. Except, of course, that this woman, Mary Bowser, isn’t a slave at all. Originally Mary Jane Richards, she grew up under Elizabeth’s care – as a young girl, she was sent North to get an education and spent time abroad as a missionary in Liberia. But she was unhappy there, so Mary decided to come home to Richmond, where she was arrested in 1860 because the law didn’t recognize her freedom. All freed black persons had to leave the state of Virginia within a year, and couldn’t return, or they risked being re-enslaved. To get her out, Elizabeth paid bail and had to say that, just kidding, she was Mary’s owner. Yikes.

Mary agrees to move into the Confederate White House, acting the part of dim-witted house servant so she can gather information. Because of course this woman can’t read; I mean, the law says so! And so she uses their prejudice against them, reading papers when the Confederate President’s away from his desk and eavesdropping on his conversations, committing them to memory. She transcribes letters and maps and then, it’s said, she smuggles them out in the first lady’s dresses. She supposedly ripped open part of Varina’s waistband, sewed messages into them, and left them with the seamstress, who let Elizabeth come and have a read. Elizabeth wrote of the arrangement, “When I open my eyes in the morning, I say to the servant, ‘What news, Mary?’ and my caterer never fails!” This woman bravely risked her life to spy for the Union in a war that would decide her fate, as did so many African Americans.

To find out more about Mary and how African American spies helped win the war, listen to/read episode 7.

9. the mail carrier:

“Stagecoach” Mary Fields

Wikicommons

How did this hardcore badass become the first African American woman to carry mail? When the Civil War ended, Mary Fields worked her way up the Mississippi River and ended up in a convent in Ohio, where she helped care for the property. Her temper was legendary. As one nun said, “God help anyone who walked on the lawn after Mary had cut it.” From there, she headed out to wild Montana, where she became tan express mail carrier: a very dangerous job indeed. “Stagecoach Mary” lived a very Wild West life: drinking, smoking, toting guns, wearing pants, fighting off wolves, and living life on the edge – and on her terms. As one Montana native said, “she was one of the freest souls to ever draw a breath or a .38."

To find out more about Mary, read this bio and listen to/read episode 11 on women in the Wild West.

10. The women who fought back, in so many ways.

Courtesy of the Library of Congress

OK, so this isn’t one woman, exactly, but I want to celebrate all the 19th-century ladies, both known and lost to history, who did what they could to survive; who fought to keep their sense of worth and who fought back against those who would oppress them.

For example, all the women of color who were abused by soldiers - North and South - during the Civil War. In the Carolinas, a doctor complained: “No colored woman or girl was safe from the brutal lusts of the soldiers--and by soldiers I mean both officers and men....” In 1864, teenaged Jenny Green, who escaped slavery, went to the Union army in City Point, Virginia. There she was raped by a Lt. Andrew J. Smith. Instead of being forced into silence, she was able to bring charges against him: she was even allowed to testify - can you imagine how much bravery that would take in this era? Her story was corroborated by William Hunter, the black chaplain of the 4th U.S. Colored Troops, and Nellie Wyatt, who also lived in the contraband camp. I’m happy to report that Smith was discharged from the Army and sentenced to 10 years hard labor.

And then there are these legends. In 1864 a group of black laundresses - Keziah and Laura Davis, Emma Smith, Elizabeth Dallas, Rose Plummer, and (yes, this is real) - Elizabeth Taylor - were accosted in their laundry hut by four white officers. They exposed themselves, made rude suggestions, and proffered a bucket of oysters as payment. One of them tried to force Elizabeth into bed with him; when she said no thanks, he called her a bitch, to which she replied that she “was no more a bitch than he was a son-of-a-bitch.” Keziah scorched the oyster man with a candle, and he later had the gall to ask her not to tell anyone about it because it would be embarrassing. But guess what? She did. And now we’re embarrassing him more than 200 years later.