Wild Western Women: Ladies on the American Frontier

In 19th-century America, the Wild West was a dream: of striking it rich, of finding fame, a fresh start, or freedom. It was a place of extremes and contradictions: full of epic landscapes and terrible hardships, independence and lawlessness and swing-door saloons.

Americans were obsessed with the West then, and they still are. But when we think of frontier legends, we tend to picture grizzled cowboys pointing shiny guns. If we see a woman at all, it’s a pretty, helpless schoolteacher or that fast-talking dancer at the local brothel.

But what was life REALLY like for women on the rugged frontier?

What prompted Victorian-era ladies to journey into such wild, unknown lands? And what kind of lives did they find once they got there? What about the women who were ALREADY there—say, Native American women, or Mexican ones?

And the ultimate question: did these women find freedom and equality in the West, or did their era’s strict rules about a woman’s place still bind them?

Grab your sunbonnet, some snake venom antidote, and your most reliable pistol. Let’s go traveling.

my resources

books

America's Women: 400 Years of Dolls, Drudges, Helpmates, and Heroines by Gail Collins, HarperCollins, 2009.

Frontier Grit: The Unlikely True Stories of Daring Pioneer Women by Marianne Monson, Shadow Mountain, 2016.

podcasts

The History Chicks, episode 115: “Belle Starr and Calamity Jane.” I didn’t use much of this information in my episode, but it helped set the scene in my brain, and I love these ladies.

DIG History Podcast, “Black Cowboys: People of Color in the West.” Written and researched by Elizabeth Garner Masarik and produced by Marissa Rhodes and Elizabeth Garner Masarik. Thanks to the amazing ladies at DIG for introducing me to Josana!

Complicated Women of History, “The Girl with the Blue Tattoo.” Thanks for introducing me to Olive Oatman! If you want more on her fascinating story than I give in the episode, clink on the link and have a listen.

online media

“Women of the Wild West.” History Detectives, PBS.org.

“Women and the Myth of the American West” by Zocalo Public Square, TIME.com.

“How the West Was Settled” by Greg Bradsher, National Archives and Records Administration.

“How the Louisiana Purchase Changed the World” by Joseph A. Harriss, Smithsonian.com, 2013.

“Western Frontier Life in America” by Richard W. Slatta, Ph.D., Professor of History, North Carolina State University.

“How Prostitutes Settled the Wild West.” Adam Ruins Everything. TruTV, 2016.

“Wild Women of the West” by Chris Enss and “Soiled Doves” by Jan MacKell. True West Magazine.

“Second To One: Mamie Majors, Colorado City’s (Almost) Reigning Madam.” Jan MacKell Collins’s author blog, 2019.

“Heroines of the Wild West You Wouldn't Want To Mess With” by Jacoby Bancroft, Ranker.com. (A nice little listicle.)

“Sarah Winnemucca.” The Nevada Women’s History Project.

“Olive Oatman, the Pioneer Girl Abducted by Native Americans Who Returned a Marked Woman” (2015) by Meg Van Huygen and “Laura de Force Gordon, Pioneering Newspaper Publisher, Lawyer, and Suffragist” (2018) by Kyla Cathey, Retrobituaries, Mentalfloss.com.

“Rise of Industrial America, 1865-1890.” American Memory Timeline, Library of Congress.

“Wyoming Women Get Right to Vote, Hold Office” by Louise Bernikow, Women’s E-news, 2003.

“Overlooked No More: Charley Parkhurst, Gold Rush Legend With a Hidden Identity” by Tim Arango, The New York Times, 2018.

“Meet Stagecoach Mary, the Daring Black Pioneer Who Protected Wild West Stagecoaches” by Erin Blakemore, History.com.

“Clara Brown.” History of American Women.

“The First (Documented) Black Woman to Serve in the U.S. Army” by Christina Ayele Djossa, Atlas Obscura, 2018.

cross country by wagon? Sign me up.

Wikicommons

episode transcript

(this won’t be exactly the same as the audio, as i add and change a bit as I record. please forgive the occasional typo..or catch them all and send me an email telling me where they are!)

HOW THE WEST WAS WON

So let’s start somewhere in the 1840s—in, oh, let’s say Ohio. You’re gazing out your farmhouse window and seriously thinking about heading out into the wild frontier. But what IS it, exactly? In the colonial era, it was anywhere west of the Blue Ridge Mountains. Anything beyond the Mississippi River is a mystery. There are rumors about woolly mammoths, volcanoes, and mountains of salt, but what life’s really like out there, pretty much nobody knows.

Things changed in 1803 when president Thomas Jefferson bought a bunch of land from the French at a rock-bottom price: $15 million, or four cents an acre. The Louisiana Purchase was one of American history’s biggest and most influential bargain purchases, winning America all the land from the Mississippi River west to the Rockies, and from Canada down to New Orleans. That’s about 827,000 square miles, or 2,142,920 square kilometers. So, about the size of modern-day France, Spain, Portugal, Italy, Germany, Holland, Switzerland and the British Isles...combined. It nearly doubled the size of the United States.

The Louisiana Purchase doubled the size of the United States. Thomas Jefferson must have been pretty pleased with himself about that one.

Courtesy of the Natural Earth and Portland State University.

It isn’t long after that, probably while celebrating his awesomeness over some apple brandy, that Thomas Jefferson sends a group of guys called the Corps of Discovery out to explore and map this newly acquired area: to chart the land, discover its flora and fauna, and make nice (or perhaps just subdue?) Native American tribes. It’s led by the wonderfully named Meriwether Lewis and William Clark, but it’s an American Indian woman who is the secret to their success. And by success I mostly mean...not dying.

Sacajawea was born to the Shoshone tribe in Idaho, but was kidnapped at age 12 by the Hidatsa, then taken to North Dakota, where she was sold and forced to marry a much older fur trapper, Toussaint Charbonneau. Every woman's dream, I’m sure. Lewis and Clarke enlisted Charbonneau’s help as a wilderness guide for their journey over the Rocky Mountains, and he brought a pregnant Sacajawea in tow. But she’s the one who proved the bravest and most valuable team member, using her knowledge of the land to help them survive the winter, and her ability to speak several indigenous languages to help them purchase horses. All with a baby strapped to her back. Hard. Core!

Sakawajea being all like, “Hey, guys, want to be a little less helpless?” I must say, Lewis and Clarke don’t look very excited about asking a woman for directions…and also they look like twins a little.

Detail of "Lewis & Clark at Three Forks", a mural in lobby of Montana House of Representatives.

Not that she got paid for her work or anything. But William Clark seems to have been quite fond of her. When she dies at the tender age of 25, he adopts her children. So there’s that.

The Corps of Discovery show the folks back home on the East Coast many things, one of them being that a trip to the other side of the continent could indeed be done. But it isn’t until the 1840s that people started heading all the way to the West Coast in large numbers. And so here we are, back at our farmhouse window, dreaming of the life we might have.

By now, several overland routes have been established across the middle west and to the West Coast. About 7 million Americans—40 percent of the populace—are living beyond the Appalachian Mountains. But why leave the safety of the known Eastern states for the wild and dangerous unknown? Most of them go in search of fortune. Or, at the very least, cheap land to buy and farm. The population is rising, especially in terms of immigrant numbers, and opportunities don’t feel as plentiful as they did. Plus, Depressions in 1819 and 1839 pull the economic rug out from under many a pair of feet.

Plus, the 1840s will see a series of American victories in terms of dominating that scary land beyond the Mississippi: the United States rises victorious from the Mexican War in 1848, gaining vast new areas of land....and, it must be said, royally screwing over Mexico.

And then there is the western gold rush. After James Marshall discovered gold at Sutter's Mill in California, a rush of gold seekers head West to try and strike it rich. These "Forty-Niners," as they’re called, include Chinese, European, and South American immigrants who all want in on the fortune-hunting game. By 1850, some 100,000 people flock to California, but they’re heading to other territories, too, chasing rumors of the next big gold strike.

The government is helping things along, as they’re eager to see people heading out to populate the West. A much bigger country full of farmers means more valuable grains that the country can export. Laws like the Pre-emption Act of 1841 and, later, the Homestead Act of 1862, mean that families can stake claims on good land for much cheaper than before. Whether or not that land’s theirs to claim is another thing, but we’ll get to that a little later.

But there is also the American obsession with “manifest destiny”. Coined around 1845, the term is meant to express an American philosophy that’s captured the culture’s imagination: that it is our birthright, granted by God, to spread the American way of life through the rest of the continent. Even if we have to push through indigenous tribes who have lived and thrived there for thousands of years. Oh dear.

Often, it’s the men folk who want to head for the hills, keen to pan for gold, or go down into the mines, or log the lush forests of the Pacific Northwest. They mostly want to leave their ladies behind in the East and send money back, but many a wife isn’t keen to be left behind. Take awe-inpsiring pioneer wife Luzena Wilson. She wrote:

“I thought where he could go I could go, and where I went I could take my two little toddling babies...I little realized then the task I had undertaken.”

GOING WEST

So we’re going: saddle up, ladies! We’ll leave in spring, so we can be sure the weather won’t be have turned too bad when we hit those craggy mountains. That’s the theory, anyway. Steam trains exist, but at this point none of them cut through the country to the other coast...the First Transcontinental Railroad won’t be up and running until the 1860s. So travel means it’s a horse-pulled wagon or nothing.

Dust, snakes, and coyotes. What’s not to love?

Courtesy of the National Archives and Records Administration.

If you’re feeling unprepared for your journey, don’t fret: there are several handy manuals to guide you. Publications like The National Wagon Road Guide and the Daily Missouri Republican are the era’s Lonely Planet guides, giving you useful tips like how long the journey west might take—three months, they say, when in reality it’s more like six. They’ll also help you figure out what kinds of things you should pack, how to cook dinner over an open flame, and how to keep your kids busy for ten hours a day in a dusty wagon. Don’t worry, these guides say: it’ll be fun, we promise! Of course, the reality of these journeys is shockingly hard.

Did you ever play that 1980s computer game, Oregon Trail? It’s essentially a Choose Your Own Adventure situation in which you try to get your covered wagon from Missouri to Washington: cross this river, or go around it? Y/N? Go through this valley, or try and find a less dangerous route? There are a lot of ways to die: measles, snakebite, cholera, drowning, pure exhaustion. But in real life, we lady pioneers won’t have the option to click Start Over.

You know when a snake features this prominently in the Menu, you’re probably in for a wild ride.

A screenshot from the computer game Oregon Trail.

First, there is the weather to deal with: there are often massive thunderstorms on the plains, with winds so bad that everything you own will be wet no matter how deep you bury it in your wagon. But there are hot, dry windstorms, too. “You in the states know nothing about dust,” one woman wrote back East. “It will fly so that you can hardly see the horns of your oxen. It often seems the cattle must die for want of breath, and then in our wagon such a spectacle—beds, clothes, victuals and children all completely covered.” And after that, in higher elevations, there is always the risk of snow. “I carry my babe and lead or rather carry another through snow and mud and water almost to my knees,” wrote that same poor woman from the crazy dust storms. “I froze or chilled my feet so that I cannot wear a shoe so I have to go round in the cold water barefooted.”

In 1841, at 17, Nancy Kelsey became the first gal to travel by wagon train all the way to California. Though she wasn’t the first person to head into the great unknown completely unprepared for what they were going to meet. Nancy, her husband, and baby daughter headed out with about 30 people, none of whom had a guide to help them – they didn’t even have a reliable map to chart their way to the coast. Still, they managed to make it from Missouri to Wyoming before getting hopelessly lost. At one point they had to ditch their wagons, leaving them to brave the elements and the wolves. Her trip was something of a comedy of errors, though I doubt Nancy was doing much laughing. Some mules fell off a cliff, and when they ran out of cows, they continued on without food in a landscape that was completely foreign to them. “My husband came very near to dying with the cramps,” she said later, “and it was suggested to leave him, but I said I would never do that.”

Imagine how it much have felt for Nancy to ring in her big 18th birthday on top of the Sierra Nevada mountains, wondering what would kill her first: natives, hunger, or frostbite. But somehow, she made it, went on to have 11 children and many adventures that make my stomach hurt to even contemplate.

A sand storm in Texas. Just another day on the farm.

Courtesy of the National Archives and Records Administration.

It costs some money to go West: buying and outfitting a wagon costs from $600 to $1000, the kind of money that’s almost impossible to save on a factory worker’s wage. That means most women who head west come from middle class farming families, but that doesn’t mean they are all ready for the harsh reality of frontier living. As a rule, these aren’t the chap-wearing rebel girls from Wild West movies. Let’s remember: Victorian-era rules of etiquette run deep.

Most ladies ride sidesaddle into the wilderness, wearing the same heavy skirts they wore at home. Many wear bonnets, not wanting to see their skin grow tan. Horrors! But desperate times often call for desperate, unladylike measures. It isn’t long before most women are getting out of their wagons and pushing them out of mud pits, not to mention learning how to fire a gun. Some even adopt the racy bloomer costume, seeing that pants are much more practical for adventuring. Those who cling on to their skirts learn quickly how easy it is to have them burst into flame around a campfire.

We lady pioneers will need strong arms, flexible ideas about personal hygiene and comfort, and a strong constitution to make it through these long days on the road. The wagons only stop rolling from dusk to dawn, and you’ll be in charge of most of what happens during those hours.

Think of the worst camping you've ever done—terrible weather, bad roads, no electricity, no porta potties, no matches, no headlamps—and times that by perhaps a million. And at the end of the day, when the wagons are circled and the animals are howling out in the darkness, who do you think is in charge of domestic duties like cooking and cleaning and starting a fire? Us ladies, naturally. Just like back at home, ours is the domestic sphere—never mind that this sphere now involves bears and rattlesnakes.

having fun yet?

Courtesy of the National Archives and Records Administration

Our new hearth also involves a lot of dirt and heavy lifting the likes of which we’ve never seen before:

“Some women have very little help about the camp, being obliged to get the wood and water (As far as possible) make camp fires, unpack at night and pack up in the morning and...have the milking to do, if they are fortunate enough to have cows.”

This isn’t a situation where you can retreat into an air-conditioned campervan and watch some Netflix over a glass of box wine. The conditions are hard and always changing, and so we ladies need to be think on our feet.

Especially on the Great Plains, where there are very few trees for fuel or cover. Often, the only thing to gather for a fire are buffalo chips—no, they are not at all like kale chips. They are dried-out buffalo poop, which must smell particularly delightful while one tries to cook over it. Some women have never cooked out in the open before. And yet, of course, they manage.

On a rainy night in 1844, one James Clyman watched a woman go about her duties with some fascination at her ability to multitask: “After having kneaded her dough she watched and nursed the fire and held an umbrella over the fire and her skillet with the greatest composure for near two hours and baked bread enough to give us a very plentiful supper.”

And, of course, these duties don't stop while you’re moving—you will not be listening to any podcasts on your road trip through the plains. You’ll be rolling out that piecrust and trying to mend clothing while jolting back and forth behind a bunch of mules. And because there isn’t much time for things like laundry, your family is probably going to spend a lot of time smelling like unwashed armpit. You’ll be lucky if you can find a river to dunk those dirty drawers in. Good luck figuring out how to hang them over the fire!

And sometimes, you’ll find something much worse: a stranded family, left helpless by the death of a patriarch. One pioneer remembered coming across: “an open bleak prairie, the cold wind howling overhead...a new-made grave, a woman and three children sitting nearby, a girl of 14 summers walking round and round in a circle, wringing her hands and calling upon her dead parent.” Kids out on the trail have to grow an emotional callous with the quickness. Sometimes they write little poems on the skulls they find along the way, leaving room for the next kid to add a few lines of their own. Kind of like a game of telephone. How fun!

Dirty diapers are a particular headache: often, all you’ll be able to do is scrape them out and reuse them. Leave something in the sun long enough and it’ll dry out! Same goes for whatever you’re using to deal with your feminine hygiene. How are we even going to the bathroom, in the middle of an open plain with many men around, you wonder? Sometimes we ladies have to band together. They often stand in tight circles, shielding a urinating lady from view of the men in their wagon train. Others just have to trot farther afield to find a private place.

Don’t be too long, though. Wagon trains have been known to leave their womenfolk behind. Take Frances Grummond. She was peeing in Sioux Indian territory when she discovered that her companions had forgotten all about her and headed on their way. Understandably, she panicked:

“In my haste to reach the road or trail I had the dreadful misfortune to run into a cactus clump. My cloth slippers were instantly punctured with innumerable needles. There was no time to stop even for an initial attempt to extricate then, as fear of some unseen enemy possessed my mind as cactus needles possessed my feet.”

She ran, her feet full of needles, for almost a mile before she found them. Yikes.

Even if things go well, you’re bound to hit trouble when the going gets rough and your cart animals start to tire. That’s when you’ll have to start making tough decisions about what to throw out the back of the wagon. You’ve brought everything you own with you, and it’s precious keepsakes and pieces of furniture that are likely the first things to go.

But don’t worry: just because your husband WANTS you to throw things out, doesn’t mean you have to. When Luzena Wilson’s husband declared they had to lose some weight, Luzena looked through supplies and said that all they could afford to get rid of was three slabs of bacon and a calico apron. But while his back was turned, she managed to wash the apron, render the fat out of the bacon, chop it and hide it all back in the wagon. Days later, her husband remarked how much better the miles were doing. Luzena just nodded her head and smiled a Mona Lisa smile.

Women going West aren’t always welcome amongst the rough and tumble. A fear of American Indians pushed our friend Luzena to beg her husband to join up with a group of prospectors, but they didn’t want her. They thought a woman and a kid would slow them down. So how glorious that, many days, later, they came upon this same group of men starving to death. She gave them food and water out of her family’s store, and they fell to their knees and begged for her forgiveness. Now that’s what I’m talking about!

Things get especially tricky for women traveling alone to meet a husband who’s already out in the goldfields. Poor Julia Lovejoy suffered it all as she traveled with her two kids to meet her hubby in Kansas: one time, while on a riverboat, a male passenger offered to give her his room, seeing as her child had measles. She moved in only to find it horrifically dirty – only a man would have a dead cat in one of his drawers. Gross. She cleaned the room, upon which point he changed his mind and evicted her. Classy. Some of the other fine sights her little family encountered on their journey: dead bodies in hallways, drunken outbursts, and dirty floors instead of beds, with little protection. I think I’ll take that covered wagon, please.

Some girls seem able to rise to such hardships. Take Janette Riker, who found herself alone in Montana wilderness in 1849 when her dad and brothers went out hunting and never came back. She built a shelter, killed an ox and salted the meat, and settled in to wait for them. (An ox weighs in around 2,000 pounds, by the way.)

Turns out she had to wait all winter, fending off the wolves, before a Native American group found her and took her to a nearby fort. Surviving here takes seriously perseverance and an iron will. Our friend Luzena said later:

“Nothing but actual experience, will give one an idea of the plodding, unvarying monotony, the vexations, the exhaustive energy, the throbs of hope, the depths of despair, through which we lived.”

THE ORIGINAL WESTern WOMEN

Of course, you’re not the first lady in the West: far from it. Spanish, Mexican, and Native American women have been here for quite a while. What happens to them are some of America’s deepest and most shameful tragedies.

Before 1846, a decent chunk of the southwest belonged to Mexico. Those who settled there before that were most certainly not doing it legally. But when the Mexican-American War came in 1846, Mexico ended up losing a huge chuck of their territory. And with so many settlers heading West, what does that mean for the many Mexicans who have lived there for generations? Nothing good.

Take Maria Amparo Ruiz, who was born to an influential family of Spanish descent in lovely Baja. She goes on to do many fabulous and racy things: marries a white Protestant military man (horrors), and goes on to write some influential plays and novels filled with biting political satire about what the United States thinks it's doing by pushing people like her around and off of their land. And like many Mexican Americans, she spends many precious years of her life fighting the people who try to take her land away from her. The rules around land titles are hazy—in some places, if land is left untended for a certain period, all you have to do is squat on the land for a while and it’s yours. All the better if they’re not white, as the law is much less likely to back their claim at all. “There is no phrase more detestable for me [than Manifest Destiny],” she wrote. “...When hear it, and I see as if in a photographic instance all that the Yankee have done to make Mexicans suffer...”

A handy map illustrating the different Native American tribes around America and their traditional lands. I can’t seem to find a consensus about which term is most respectful to use: Native American, or Indigenous American, or American Indian, so I’ve used them all and kept my fingers crossed. Map from Historyonthenet.com. There’s another cool map that shows tribes before colonization, which you can find here.

It’s hard to capture what an indigenous woman’s life is like before pioneers come along. There are many different Native American tribes operating in the 1800s, and they all live with different languages, religions, and ways of life. Those who live on the Great Plains are mostly nomadic hunter gatherers, moving wherever the buffalo roam.

In many of these groups, women run the home. They are in charge of skinning and butchering the buffalo, curing their hides for teepees and clothing, and preparing the meat to last through winter. It takes some 22 hides to make one teepee, which women sew themselves, by hand.

So they’re pretty horrified to see how fast white settlers are killing them. “My heart fell down when I began to see dead buffalo all over our beautiful country,” said Pretty Shield, a Crow woman. “Killed and skinned and left to rot by white men...” These women watch as their way of life changes before their eyes.

One of the saddest fates that native people have to suffer is what we now call the Trail of Tears. Some 125,000 American Indians living in the southeast were unceremoniously forced to march West, well past the Mississippi River. The Supreme Court objected to the worst of these crimes in the 1830s, affirming that native nations are sovereign nations, that doesn’t stop people covetous of native land from removing them by any means necessary. In 1836, the federal government drove the Creek tribe from their land along this brutal Trail: 3,500 of the 15,000 of them don't survive it. Some stay and fight, and are forced out at gunpoint.

Of course, some indigenous people and white pioneers make friends and allies. But a potent mix of ignorance, greed, and fear drive many settlers to commit horrible atrocities against the people who were there before them. In 1864, one Colonel John Chivington will order his troops in Colorado to attack an Arapaho and Cheyenne village—150 people are killed. So it’s no surprise that some native women are so terrified of white people that they bury their children in shallow holes when soldiers ride into their settlements. That is one of Sarah Winnemucca’s earliest memories of her childhood. She said:

“ They came like a lion, yes, like a roaring lion, and have continued so ever since.”

This Paiute woman was born in western Nevada in 1844, given the name Thocmetony, or “shell flower.” Her grandfather was chief of the Paiute nation. When he was told about settlers encroaching on his territory, he wasn’t scared. He clapped his hands and said, “My white brothers–my long-looked for white brothers have come at last!” He even helped General John Fremont in the Bear War, fighting against Mexican control of California. But her father was suspicious, and with good reason.

She grew up with a foot in both worlds, learning several languages, and became a bridge between the cultures. Later, she went to Washington to lecture and speak out against the abuses being laid on her people. “If women could go into your Congress,” she wrote, “I think justice would soon be done to the Indians.”

The fab Sarah Winnemucca, who thought that if white women would just step up to the plate on indigenous rights perhaps they could get some shit done.

Wikicommons

Some white settlers feel bad about the way indigenous people are being treated. But others...well. Not so much. “I used to be sorry that there was so much prospect of their annihilation,” wrote one Oregon woman. “Now I do not think it is to be much regretted. If they all die, their place will be occupied by a superior race.” Yikes, lady.

One of the biggest fears for Eastern migrants is of what happens if they encounter Native Americans. And though in the grand scheme of things, the number of unprovoked attacks on migrant families isn’t huge—and perhaps they’re even understandable—there are some terrifying cautionary tales. In this era, you don’t have to look far to pick up a novel about white women violently taken by savage natives–if you’ve seen Godless on Netflix, you’ll know what I mean. And it is true that some indigenous men rape and kill women they capture. Some are even taken away as slaves.

This is a thorny issue. As with every ‘good girl, bad guy’ story, these captured women’s lives and experiences are varied and not always bad. Take young Olive Oatman. In 1851 a band of Indians murders her entire family while they’re traveling through Arizona, taking Olive, age 14, and her younger sister Mary Anne off to become their slaves. They live that way for a year, forced to do chores and beaten when they don’t do them properly, until they were swapped for supplies with a group of Mohave. The family of a tribal leader adopted and raised them, treating them as one of their own. The girls spent years with this community, becoming one of them; so much so that when a band of white traders stayed with them for weeks, neither or the girls sought to make themselves known. They even got blue tattoos on their faces, which Mohave Indian women got to make sure they’d meet ancestors in the afterlife.

Mary Ann died of starvation during a particularly bad harvest. Eventually, Olive’s true identity was discovered, and she was reunited with the brother: turns out he hadn’t actually been killed in the mass murder of her family. Who knows how she was feeling: sadness, elation, terror, confusion? Her adopted mother cried when Olive left, and when she got to the fort, Olive cried into her hands.

America wanted to know: what had it been like, living amongst the natives? Had they made her get a tattoo, or had she wanted it? Had she been forced to marry one of the local boys, or done it of her own free will? But always, the reality of her complicated growing up stayed murky.

In her public lectures about her time with the tribe, she sometimes calls them “savages.” Perhaps because that’s what white audiences want to believe Native Americans are. It's much easier to justify robbing people of fertile land when you believe them to be devils. But privately, she seemed to mourn the family she’d lost. She paced the floors at night in her brother’s house, always restless. She never was quite able to embrace the more “civilized” world.

Olive Oatman, the girl with the blue tattoo and perhaps a touch of Stockholm syndrome?

Wikicommons

BEING WEST

So now we’re here, in the West. What are we to expect upon arrival in Nebraska or Montana or Oregon? You might thank God you made it. Or you might indulge in a good bout of crying. That’s what one girl recalled her mother doing when their wagon pulled up in front of a tiny house made of sod. Honey, we’re home! “I remember how her face looked as she gazed about that barren farm, then threw her arms around his neck and gave way to the only fit of weeping I even remember seeing her indulge in.”

The landscape is foreign, unforgiving, and scary to many Eastern ladies. Especially those dusty, wind-swept plains that stretch as far as the eye can see. One pioneer bride begs to go with her husband on a trip to purchase wood, and when she sees trees – something she hasn’t seen in two years – she throws her arms around a trunk and clings on like it’s a long-lost sister.

In these early days of westward migration, women are scarce out here. Out of the 50,000 people who head for the plains in 1849, only about 5,000 are of the female persuasion. Towns tend to be little more than a collection of shacks and men—and they are, in fact, often quite wild. If a mine does well, the population around it swells, creating a demand that the supply can’t keep up with. There’s nothing like a half-formed infrastructure and the looming prospect of starvation to put the “Wild” into West.

Houses are scarce, too. So, ladies, if you’re hoping for a nice little three-bedroom cottage, don’t get your hopes up. Your first home is likely to be a dugout, which is essentially a fancy cave dug into the side of a hill. Keeping house in a cave is, to put it mildly, challenging. One cave-dwelling girl reports that when it rained:

“ ...we carried the water out with buckets, then waded around in the mud until it dried up. Then to keep us nerved up, sometimes the bull snakes would get in the roof and now and then one would lose his hold and fall down on the bed, and then off on the floor.”

And what does one do when it’s raining bull snakes? Chuck them out the front door, of course! “Mother would grab the hoe and there was something doing and after the fight was over Mr. Bull Snake was dragged outside.” You’ll need to get over your fear of snakes quite quickly. One woman in Texas said she killed some 186 of them in one year – they are particularly famous for appearing in people’s beds. *Shiver.*

Or you might be living in what’s called a “soddy:” a structure made of sod bricks that weigh upwards of 50 pounds each. Sure, some day you might make enough money to build a proper log cabin, but most of your earnings will need to go toward livestock and equipment. So you’d better get comfy in your dirt hut, with its gravel floors. Have YOU raked your living room floor today?

Everything you own will have to be multi-purpose. If it can’t be used as a dress, a tablecloth, and a picnic sack, then it’s not going to make the cut. On the day of their wedding, one couple stood behind a wax sheet in a corner of their soddy to get ready while guests milled about on the other side. Once they were married, that same sheet was used as a handy tablecloth for the wedding supper.

For those keen to nest, there are things you can do to make it feel homey. “The wind whistled through the walls in winter and the dust blew in summer, but we papered the walls with newspapers and made rag carpets for the floor and thought we were living well,” wrote pioneer enthusiast Lydia Lyons. "...very enthusiastic over the new country we intended to conquer.” Reading the spines on a bookshelf at a friend’s house is a popular 21st-century past time, but have you tried ‘reading the walls’? Now that’s a fun way to pass the pioneer lady’s time. You can also spend the long winters making rag rugs. They’re pretty, and they also mean that your children are less likely to get gravel or splinters just from crawling across the floor of a morning.

But conquering this wild landscape is no small feat, my desert flowers. Your home is dark and the windows are small: most of them won’t have any glass panes in them. Rain and mud is going to soak into those rugs and through your newspaper walls no matter what you do. You’ll also be fighting 50-mile-an-hour winds, which shred the clothes you leave out on the wash line and make sure that furniture is always covered in a layer of dust. You'll also enjoy flash floods and ravenous prairie fires while huddled in your house made almost entirely of wood. Snowstorms might cut you off from the world for weeks, and there are no emergency services to come and get you.

Then there is perhaps the worst plague of all: grasshoppers. These ravenous devils sweep through in huge clouds and eat absolutely EVERYTHING: crops, furniture, clothes, fences. They'll eat all the fruit off of yours peaches, leaving nothing but the shriveled pits dangling from the branches. “They commenced on a 40 acre field of corn about ten o’clock and before night there was not an ear of corn or green leaf to be seen,” one girl lamented. Another lady tried to cover her garden with burlap sacks, but those suckers just ate through them. They could decimate your livelihood and your food stores in just one afternoon.

If you’re a lady in the southwest, you’ll need to make sure your bed is at least two feet from the walls, unless you want to wake up cuddling a scorpion. Fleas are bad, too. Native American women build temporary structures that are easy to burn down when the infestations grow to be too much, but pioneer women want to create a kind of permanent sanctuary. And that is going to be an uphill battle. And don’t forget about the mosquitos. To keep them at bay, you might burn buffalo chips inside your house—yes, dried poop again, we will never escape it. Young children are often sent out to collect them before winter sets in. Sounds like a fantastic scavenger hunt!

Food out here isn’t bountiful, either, in these very up-and-coming towns. Much of what you’ll be eating is dried and salted. We’re talking hard tack, buffalo berry jelly, chokeberry pie, and every form of corn you can possibly think of. Food stores get so low at Louise Clapp’s mining settlement that she has nothing left to feed her family but dried mackerel and “hard, dark hams...[that] nothing but the sharpest knife and stoutest heart can penetrate.” The same is true for clothing. Unless you’re a lady of the evening in a bawdy house, the farming lady has little need for all that corseted finery they wear out East. Given how far they often are from a town center, homesteads and cattle ranches need to be self-sufficient, and that includes your daily apparel. Your typical outfit will be a dress made of calico or gingham, an apron, and a bonnet to try and keep the sun from turning your face into an alligator suitcase. You’ll also card wool or flax and spin it with one of those huge spinning wheels, then make it into everything from mittens to stockings. If you don’t know how to knit, time travelers, now’s the time to start getting crafty. If those wear out, you might go through that trunk of bed linens you brought West with you and sew something out of those. If you get desperate, you might even make undies out of grain sacks. Burlap undies, anyone? Ouch.

What to do to keep busy out here, you wonder? Join a book club and make some lady friends to share your trials? Maybe not. Most Western towns are loose and mostly man-filled places, particularly early on, which means it’s going to be hard to make good female friends. There is the occasional dance or picnic to commune over, but farm gals often spend long stretches of time with only family for company.

Some women get so lonely they start talking to their horses and livestock. If we did not have a lot of house work to do,” wrote young Margaret Armstrong, “we would be at a loss how to kill time.”

Outside a dance hall in Arizona. Have fun: you probably won’t see any of these people until after the winter thaw.

Courtesy of the National Archives and Records Association.

WOMEN IN A MAN’S WORLD

The fact that most western settlements are filled almost entirely with very smelly dudes presents both an annoyance and a problem. Many western belles find themselves the object of ardent and aggressive courting from dozens of suitors, whether they’re interested or not. Men are so desperate for all things sexy lady that they’ll pay just to see a pair of women’s undergarments: she doesn’t even have to be wearing them. Married men who don’t bring their wives to social functions so that other men can dance with them are considered extremely rude.

So it’s hard to know if a man is courting you because he likes you, or just because you’re a real live lady living within a certain radius. “Even I have had men come forty miles over the mountains just to look at me,” wrote Luzena Wilson. “And I never was called a handsome woman, in my best days, even by my most ardent admirers.” The sister of one Mrs. Reed had some 40 men paying her court—so many they had to work out a system. Only six callers could visit the house at a time, and each had only four minutes of sofa time with the lovely lady: a Bachelorette-type situation, to be sure, minus the mixed drinks and hothouse roses.

Sometimes these matches are about love or lust, but sometimes they’re about convenience. Once woman in Oregon recalled a man galloping up to her father to ask if he could marry one of his daughters, seeing as married men were entitled to a certain amount of land. He wasn’t fussed about which one: any would do. Sexy!

But enterprising ladies look at these drooling fools and see an opportunity. As we talked about in episode four on sex in this era, Wild West towns provide a very…pressing need. Enter prostitutes, or the ladies we’ll delicately call the “fair but frail.” Though most of these ladies aren’t frail in the least. In a country where lucrative employment opportunities are few and far between, particularly for a single girl, a soiled dove in a town full of men can make an absolute killing. At just 19, a lady of the evening named Mattie Silks opened a brothel in Illinois. She went on to own several across the West, making mad money, taking many lovers, and—this is just a tall tale, but it’s too good not to mention—supposedly participating in a topless duel.

Get it, girl.

“I went into the sporting life for business reasons and for no other. It was a way in those days for a woman to make money and I made it.”

- Mattie Silks. Wikicommons

While a domestic servant on the East Coast makes some $8 a month, there are towns in the West where a Cyprian woman can make $16 bucks in just one evening simply by being a man’s dinner table escort. “Nearly all these women at home were streetwalkers of the cheapest sort,” said a Frenchman traveling through the West. “But out here for only a few minutes, they ask a hundred times as much as they were used to getting in Paris.”

These women aren’t free and easy—like their sisters on the East coast, many have to hand over much of their wages to madames for their room and board, and the same worries apply. Feather boas and fringed pantaloons aside, it’s far from glamorous for many. With such high demand, payday at the mines can see some girls servicing up to 80 men in an evening. They suffer from untreatable diseases, a high suicide rate, and ill-done abortions.

Hello, boys. Or girls, whatever. Just so long as you’ve got cash in hand.

Wikicommons.

Sometimes, prostitution offers us ladies an opportunity to get ahead and live an independent life. But for immigrants, that often isn’t the story. Particularly Chinese girls, who are stolen off of the streets of Canton and sold into unspeakably horrible sex slave situations in cities like San Fransisco. Later in the century, a 25-year-old dynamo named Donaldina Cameron will lead a crusade to save these women and stop the Chinese slave trade to the West. She leads police raids on brothels and gambling dens, hacking through doors with her own two hands, and then helps these women find jobs and stable husbands. One of these, Yoke Keen, will become the first Chinese woman to graduate from Stanford.

But some Western soiled doves turn their profession into a prosperous business that influences entire regions. They bring in mad business, and thus red light districts are the social center of town. Every boom town has a strip of brothels that provide more than just a good time: they are a place where men can talk freely and do discreet business, and brothel girls prove good secret keepers. Thus Cyprian ladies have more respect, and more power, in the West than almost anywhere else. Wealthy madames become pillars of their community. They use their wealth to open schools, support injured miners, fund relief aid after mine and natural disasters, and help women less fortunate than they. They are astute businessladies, too – their investments win them freedom, but also a foothold in politics. Maybe that’s why the West gives women the right to vote WAY before the East does.

In the late 1860s, by a vote of 13-6, Wyoming passes a bill giving women the right to vote and hold office. On September 6, 1870, a posse of ladies led by 70-year-old housewife Louisa Ann Swain will march to the polls in Laramie, making them the first to vote in the United States. Well, legally vote, anyway. And this territory aren’t giving up that right to join the Union as a state, either, even though Congress objects:

“We will remain out of the Union a 100 years, rather than come without our women.”

Suffragist Susan B. Anthony is telling every gal who will listen to head on over to the earthly paradise that is Wyoming.

One of the women who gets suffrage passed is six-foot-tall, 57-year-old Esther Morris, who becomes America’s first female justice of the peace. During 8 1/2 months in office, she adjudicates more than 40 cases. Wyoming sees women serve on juries; they push for saloons to be closed on Sundays; female teachers get equal pay and parents have equal rights over their children. Damn, Esther!

Though of course, in her time as judge she has to deal with as many annoying hurdles as political women in our century. There’s the press, for one, which makes sure to write more about what she’s wearing than any of her actual rulings. And there are guys like her predecessor, who refuses to hand over any of his papers on her first day. Women of the West feel compelled to write home to Eastern newspapers, assuring everyone that voting isn’t stripping ladies of their femininity, and Esther has to defend being a working mother. “in performing all these duties,” she said, “I do not know as I have neglected my family any more than in ordinary shopping.”

The first 12 states to give women the vote are ALL in the West. Surprising this suffrage situation may seem, but it makes sense if you think about it. With so few women, it's not like letting them vote is going to topple the patriarchy. As much as I'd like to think that these men are just more enlightened—and given how tough life in the West is for all, I’m sure some are--these men just have different priorities. Giving women the vote is a way to entice more of the fairer sex to move on out to the territories. It’s like a huge roadside billboard: “Come for the vote, stay for the studly miners!”

WORKING GIRLS

What are we doing if we’re not inclined to take up sex work or be a suffragist? It depends on where you are. Very few women take up mining or panning for gold, though there are a few. Most of us ladies in mining towns are working as laundresses, seamstresses, cooks, teachers, or boardinghouse operators. Or you can become an entertainer. The money tends to be good, and the audiences here are so forgiving that you don’t have to be able to sing or dance at all!

Lola Montez makes bags of gold with her version of the classic Spanish Spider Dance, in which she gets up on stage and dances around as if she’s trying to shake off a horde of tarantulas. She even uses fake spiders to complete the effect.

dance, lola, dance!!

Courtesy of the Library of Congress

Given the shortage of skilled workers in the West, the normal rules about what sorts of jobs are appropriate for us ladies do not apply. Here, too, enterprising ladies have an opportunity.

It’s often said that the real gold is to be found in selling supplies to the miners, and that certainly proves true for our friend Luzena Wilson. As a rule, men of this era know how to cook precisely nothing for themselves. So it’s no surprise to Luzena when a guy comes up to her campfire one day and offers her $10 if she’ll serve him some food. In the West, her domestic goddess-hood isn’t about being the Ideal Woman: it's a business opportunity. Later, she buys two boards to form a table and, she said, “when my husband came back at night he found, mid the weird light of the pine torches, 20 miners eating at my table. Each man as he rose put a dollar in my hand and said I might count on him as a permanent customer.”

Another woman amidst the California gold rush wrote that she made $11,000 making bread and cakes with just one cast-iron skillet. Whaaaat?! But Luzena made $20,000 in 19th-century money in just six months. That’s the same amount I made in 2010 money with my first job in publishing. Luzena, teach me your ways!

But we ladies aren’t just earning a crust by baking some. Women of the West are becoming doctors, dentists, lawyers, real estate agents. The appropriately named Laura de Force Gordan becomes many of these things. This prominent Spiritualist medium goes on to give the first recorded speech on women and suffrage in San Fransisco, the first woman in the country to publish a daily newspaper, and–just to keep us guessing–one of the very first lady lawyers in the state of California.

One woman wrote to a friend back East:

“A smart woman can do very well in this country. It is the only country I was ever in where women received anything like a just compensation for work.”

Not that the work is easy, and it doesn’t always pay well. Teaching is a difficult gig everywhere in America, but particularly so out on the rough frontier. Like the soddy you live in, your schoolroom’s cramped, you have too many students, and perhaps no firewood to keep you warm. Our doctor friend Elizabeth Blackwell gets her start as a teacher in the West, where she said the schoolroom was so cold she had to wear gloves at all times. Many of them don’t even have an outhouse.

We ladies are also getting into rougher work, too. Some of them do it openly as women, and because the West has looser rules in the realm of place and propriety, they often get away with it. But just like our secret lady soldier friends back East, many of them are donning the breeches and living as men.

Mail delivery and stage coach driving are both seriously dangerous professions. You’re riding over rough roads over desert plains and over mountain passes, trying to keep your wheels from slipping into gorges. You’re always at risk of running into outlaws or overturning in a pile of snakes. So you’d better have a gun and know how to use it. California’s “One-Eyed Charley” Parkhurst sure does—he is one of the toughest and most famous of them all.

It wasn't until Charley died that anyone knew she was actually Charlotte, an orphan from New Hampshire who sought to reinvent herself out West in the 1850s. She was a dependable stage coach driver, getting huge amounts of gold across dangerous terrain. Her nickname wasn’t hyperbole, either: she lost her eye when a horse kicked it. As the New York Times said of her some 100 years later, "The state lines of California in the post-Gold Rush period were certainly no place for a lady, and nobody ever accused Charley of being one.”

One-eyed Charley Parkhurst. It’s more intimidating if you don’t use an eyepatch!

Wikicommons

THE HEIGHT OF THE WILD WILD WEST

It isn’t until after the Civil War wraps up in 1865 that we see the true height of what we think of as the Wild West period. People pour into the frontier between 1860 and 1890, partly because the railroad makes it much more accessible, and partly because of government incentives that promise families 160 acres if they vow to farm it for at least five years.

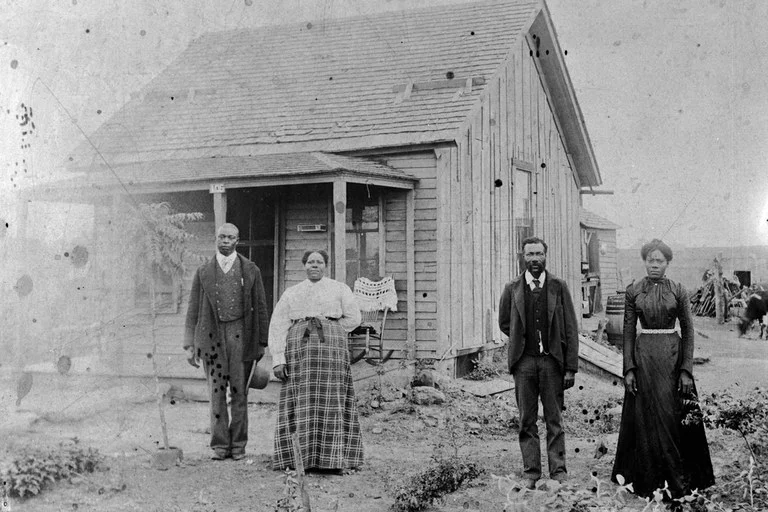

But many African American women head West in search of equality, and to escape the terrible persecution they’re experiencing in the South. It’s a hard journey for them in even more ways than their white sisters, as they have to deal with angry white Southerners who aren’t keen to lose their cheap labor force. In the 1870s, thousands of black people—called the Exodusters—flee to Nicodemus, Kansas, hoping to find community and a freer life than what they left behind.

Settlers in Nicodemus, Kansas. Many African Americans, called “Exodusters,” fled the horrible Reconstruction South with the hope for better opportunities there.

Wikicommons

For those who venture farther, they suffer the same hardships and privations as white settlers, but they also suffer a particularly double-edged sword: fewer people and harsh conditions mean less discrimination, but it also means a deeper isolation. “I ain’t got nobody,” said an African American pioneer woman named Eliza. “...and there ain’t no picnics nor church sociables nor buying out here.”

And then there are black women who go West alone. They tend to be real firebrands, and there’s work and opportunity for those looking to find it.

Born into slavery in Virginia, Clara Brown later talks her way onto a wagon train by promising to be the prospector’s cook and laundress. She walks most of the 700 miles. In Denver, she makes a boatload of money as a professional laundress to the city’s many dirty and domestically hopeless gentlemen, then wisely invests it in local businesses and real estate. This woman lovingly called “Aunt Clara” turns her house into a hospital and home for the lost and impoverished. After the Civil War, she also uses her money to search for her husband and kids, who had all been sold away. She doesn’t find them, but still manages to bring 26 formerly enslaved people back to Colorado and helps them find jobs and places to live. Clara is in her seventies when she’s finally reunited with one of her daughters. She is one of the first and most beloved black philanthropists in the West.

And then there’s Mary Fields, who works her way up the Mississippi River and ends up in a convent in Ohio, where she helps care for the property. Her temper is legendary. As one nun said, “God help anyone who walked on the lawn after Mary had cut it.” From there, she heads out to wild Montana, where she becomes the first African American express mail carrier. “Stagecoach Mary” lives a very Wild West life: drinking, smoking, toting guns, wearing pants, fighting off wolves, and living life on the edge – and on her terms. As one Montana native said, “she was one of the freest souls to ever draw a breath or a .38.”

TRULY WILD WOMEN

Ladies of the West get in on the Civil War as soldiers, too, and often don’t have to pretend to be men while doing it. Their regiments are more likely to just accept their offer to serve.

After fighting and being injured several times under the name William Cathey, Cathay Williams becomes the only documented female Buffalo Soldier: that's the first African American peacetime army regiment. She is a bit hard done by, though, our Cathay. “The men all wanted to get rid of me after they found out I was a woman,” she said. “Some of them acted real bad to me.” Like many lady soldiers, her pension request is later denied.

And, of course, you can also get involved in serious Wild West lawlessness: gambling, stickups, and highway robbery. The stories of the women who do are the stuff of legends, where fact and fiction are often hopelessly intertwined.

Eleanor Dumont becomes one of the first and most successful female gambling operators in the West. Operating under the outrageously wonderful name Madame Mustache, she arrived in San Fransisco in her twenties and proceeded to outgame everybody else at the table, buying champagne for the losers so they wouldn’t feel TOO bad. She even opened her own luxury gambling parlor. She used her winnings to purchase a cattle farm, and when her manager Jack McKnight ran off with her money, legend has it she hunted him down and kill him with a shotgun. Sorry ‘bout it.

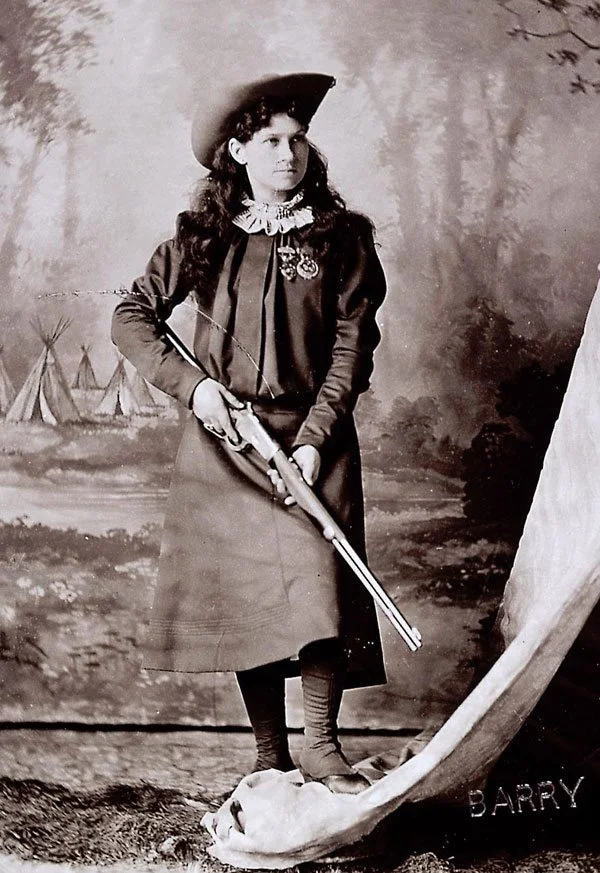

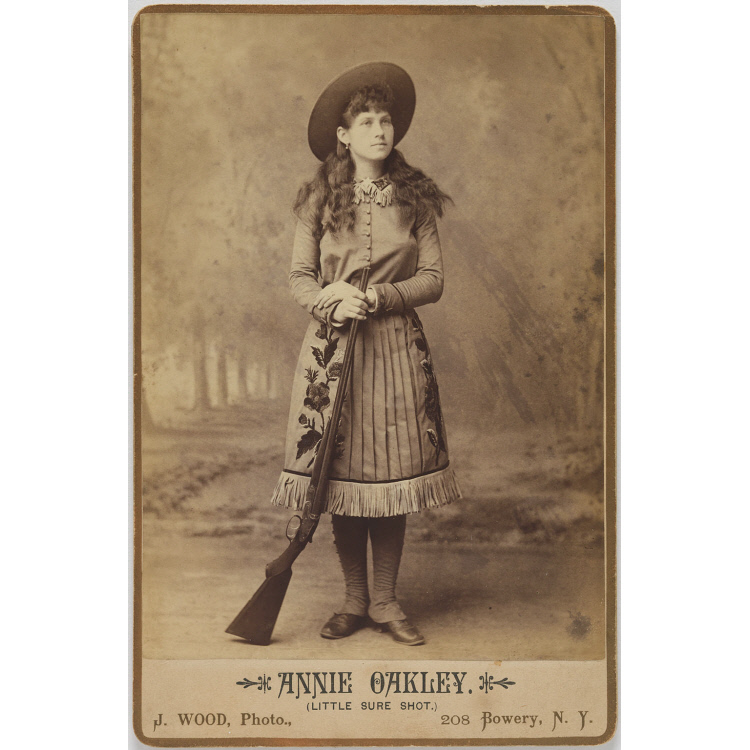

Later in the century, two women with guns will become national sensations. Annie Oakley makes quite a splash with her fancy shooting, which she learns after her father dies and she has to hunt in order to support her family. She becomes famous while shooting for Buffalo Bill’s Wild West Show, where she wows crowds by hitting very tiny targets like cards and the tips of cigarettes from the back of her moving horse. But she refuses to ever ride anything but sidesaddle, or to wear pants during her act, however practical. In doing so, she proves that one can be a lady and also shoot at things.

Martha "Calamity Jane" Canany is a different story. She turns herself into a legend mostly through shameless self-promotion, drinking hard and taking lovers, all while wearing male attire. But while everyone loved Annie Oakley, in reality Jane had fewer fans. The West is a place of opportunity and of greater equality for women, yes. But just like back East, society isn’t always kind to women who want to live a life outside the lines.

Then there are the gunslingers who actually commit crimes. Pearl Hart holds up stagecoaches in Arizona with her hair cut in a bob and a proper cowboy outfit, then escapes from jail. The "Bandit Queen” may be an outlaw, but I think what she has to say during her trial is pretty fair: “I shall not consent to be tried under a law in which my sex had no voice in making.”

For women, the frontier was both a terrible unknown and a tantalizing promise. Enterprising souls with a fondness for wide-open spaces could find freedom, and opportunities that once eluded them. Those who lived there before the pioneers found fought back as they watched their way of life change forever. The West is full of stories of heartbreak and triumph. But none would be the same without Wild West women, who showed incredible grit, resourcefulness, and bravery in an unforgiving land.

And it’s with an image of a lady pioneer riding off with her guns into the sunset that Season 1 of The Exploress comes to an end. As sad as I am to leave mid-19th century American behind, we have new countries and time periods to explore—new horizons to adventure to.

Until next time.

voices

Nancy Wassner

John Armstrong

Edie Chevalier

Kaitlin Seifert

Kayla Knight from the Get Grimm podcast

Heidi Bennet from the Vibrant Visionaries podcast

Jenirae Reynolds from The Womansplaining Podcast

Amanda Iman from Amanda’s Picture Show a Go Go

music

All music is royalty free and licensed from Audioblocks.