Walk Like An Egyptian: A Lady’s Life in Ancient Egypt

WHAT WAS LIFE LIKE FOR WOMEN OF THE ANCIENT WORLD?

I work as an editor – that’s my day job – shaping books about adventure, travel, science, and, of course, history. But when I get handed a book about ancient history, I can’t help but want to hand it back. It’s a researcher’s nightmare: dates are never certain, names, places, times, all up for debate.

And trying to understand a woman’s life in the ancient world? It’s a little like squinting through very smoky glass. That glass was mostly made by men: they wrote down the stories of ancient women, defining them through their own lenses and prejudice, turning them into what suited their narrative: saints, seductresses, jokes, cautionary tales. We have so few direct quotes from these women. But they’re there, if you only look hard enough. And because I love a challenge, I want to try and hear their voices through the smoke.

Just remember, as we go on this journey into the faraway past, to take everything with a grain or two of salt. To go so far back means relying on primary sources that weren’t always concerned about accuracy. It also means being imaginative: taking what we think we know and filling in the gaps with our own conjecture.

Let’s start with the civilization I’ve been obsessed with since elementary school, full of incense, gold leaf, and kohl eyeliner. Let’s travel back to ancient Egypt.

Of all the civilizations in the ancient world, Egypt was perhaps the most prone to the miraculous. “There is no country that possesses so many wonders,” wrote Greek historian Herodotus,“nor any that has such a number of works that defy description.” They invented many wonders: the 365-day calendar, breath mints, paper, the ramp and lever. They refined geometry, perfected irrigation and ship building, and built pyramids so tall that no architect would match them for thousands of years to come.

And then there’s this particular wonder: ancient Egyptian women had more freedom and power than anywhere else in the ancient world. They could own property, get divorced, hold down jobs, demand alimony. They ruled as pharaohs and were revered as goddesses. Why was Egypt such an exception to the ancient rule? What did these freedoms actually look like in practice, for commoners and queens? What did their lives really look like?

Grab a linen sheath, your dangliest gilded earrings, and a whole lotta sunscreen. Let’s go traveling.

MY RESOURCES

Books

Ancient Egypt: Everyday Life in the Land of the Nile. Bob Brier & Hoyt Hobbs. Sterling Publishing, 2009. (This was mega helpful as a reference when it came to all the different aspects of Egyptian life: such a great overview of the nitty gritty!)

Cleopatra: A Life. Stacy Schiff, Virgin Books, 2010.

Contraception and Abortion from the Ancient World to the Renaissance. John M. Riddle, Harvard University Press, 1994.

Dancing for Hathor: Women in Ancient Egypt. Carolyn Gaves-Brown, Continuum, May 2010.

Histories. Herodutus.

When Women Ruled the World: Six Queens of Egypt. Kara Cooney, National Geographic, 2018.

Women in Ancient Egypt. Barbara Watterson, Amberley Publishing, Feb. 2013.

Wonders of the Ancient World. National Geographic Special Editions, 2015.

podcasts

The History of Egypt Podcast by Dominic Perry. (If you’re into Ancient Egypt, this podcast is amazing: very thorough, scholarly, and with tons of details that help bring ancient Egypt to life.)

online

“10 Amazing Egyptian Inventions.” Jonathan Atteberry & Patrick Kiger, HowStuffWorks.com.

“A Brief History Of The Menstrual Period: How Women Dealt With Their Cycles Throughout The Ages” by Lecia Bushak, MedicalDaily.com, May 2016.

“A Day in the Life of An Ancient Egyptian Doctor.” Elizabeth Cox, TED Ed, July 2018.

“Ancient Egyptian Love Poems Reveal a Lust for Life.” Cameron Walker, National Geographic, April 20, 2004.

“Egyptian Customs.” Livius.org.

“For Ancient Egyptian Pharaohs, Life Was a Banquet, But the Afterlife Was the Greatest Feast of All.” by Salima Ikram. Atlas of Eating: Smithsonian Journeys Travel Quarterly. Feb. 2017.

“Ground Up Mummies Were Once an Ingredient in Paint.” Rose Eveleth, Smart News, Smithsonian.com, April 2014.

“Nine Forms of Birth Control Used in the Ancient World.” Suzanne Raga, Mental Floss, Jul. 2016.

“400 BCE-1965: Vintage Contraceptives.” Chris Wild, Mashable.com.

“Contraception in Ancient Egypt: Hormonal Birth Control, Pregnancy Tests, and Crocodile Dung.” Jessica Cale, Dirty Sexy History blog, Dec. 2016.

“Menstruation, Menstrual Hygiene and Woman's Health in Ancient Egypt” by Petra Habiger, Mum.org, 1998.

“Seshat,” “Beer in Ancient Egypt.” Joshua J. Mark, Ancient History Encyclopedia. (I used many of their articles as reference materials).

“The underworld and the afterlife in ancient Egypt.” Australian Museum, Nov. 2018.

“A History of Western Eating Utensils, From the Scandalous Fork to the Incredible Spork.” Lisa Bramen, Smithsonian.com, 2009.

“Women in Ancient Egypt.” James C. Thompson.

“Great Pyramids of Giza.” Simple History, YouTube.

Let’s Dive In!

A fresco of lady dancers and musicians from the tomb of Nebamun, Wikicommons.

episode transcript

keep in mind that i chop and change things a bit as i record. I try my best to avoid spelling mistakes, but sometimes they slip in: forgive me.

First, let’s define what we actually mean by the “ancient world.” We’ll pick up our explorations around the time when we humans start making things out of bronze and developing written languages - so, during the Bronze Age, which starts around 3200 BCE. From there, we’ll travel on through the age of classical antiquity all the way up to the fall of the Roman Empire in 476 CE. That’s over 3,000 years of time-traveling possibilities! So, a lot of eras to splash around in.

But first, let’s define what we mean by Ancient Egypt, because we’re talking about a HUGE swathe of time. We tend to think of it as one colorful, sand-blown sweep of grand pyramids, huge statues, and guys wearing eyeliner. But this isn’t like Season 1: we’re not looking at a specific slice of a century. We’re examining a civilization that rocked out for some 4,000 years. You could fit United States history, starting from the Declaration of Independence, into Egypt’s timeline some 16 times; Australian history, starting with its independent nationhood, would fit in 34 times.

Historians split ancient Egypt’s timeline into several different periods: picture it like one of those old-school wooden roller coasters. As we chug up the first hill, we’re in the pre- and early dynastic periods, which covers the beginnings of ancient Egypt from around 4000 BCE to 2686.

After that, we’ll hit three high points: times when everything was going well, the political center held strong, and the economy was stable. These are called the Old, Middle, and New Kingdoms. Between them are the dips: two low points when things were in chaos, Egypt was divided, and/or it was dealing with foreign invaders, called the Intermediate periods. From 1069 to about 30 BCE, we have the Late and Ptolemaic periods, when Greece slithered its tentacles into Egypt. Egypt’s last lady pharaoh, Cleopatra, was actually Greek, and by the time she ruled, the great pyramids were already ancient history. That was right before the age of pharaohs come to an end and Egypt became a Roman province.

Historians break it all up into numbered Dynasties, each one representing a different ruling family, from Dynasty 1 all the way to 33.

Has this roller coaster made you feel like spewing? I feel you. But never fear: I’ve created a nifty lady-centric timeline for you, as I think it always helps to have a visual…

This ladycentric timeline should give you a general sense of what happened when and what order the dynasties went in. We’re talking about a huge swathe of time! But really, this timeline only comes into its true majesty when you see it blown up to poster size: you can get it at A2 size in my Etsy merchandise shop.

While we’re talking time spans, consider this: less than 200 years ago, many of us were wearing corsets and still working on flushing toilets. Now we have iPhones and ships that go into space. Given how quickly things can change, it’s pretty amazing how little Egyptian society did over those thousands of years. If it ain’t broke, don’t fix it.

Let’s slip into life in 1460 BCE, during the 18th Dynasty, right in the middle of the New Kingdom that many consider ancient Egypt’s “golden age.” We’re living in the capitol city of Thebes.

Let’s hover over the city for a minute, looking down on the land—if you’d like to see it on paper, go back to the show notes and check out the handy map I made you, labeled with all of the places and names you need to know…

This ladycentric map of ancient Egypt should give you a feel for where all of our ladies were operating from. If you like what you see, order a printed copy of this poster in my Etsy merchandise shop! I have it framed above my mantel right now and it looks fabulous.

Right now, in this time period, Egypt’s richer and more prosperous than pretty much anywhere else. How did it become such a force to be reckoned with? Well, there’s a reason Herodotus said that “Egypt is the gift of the Nile.” The Nile is the longest river in the world, even in our century: some 4,132 miles (or 6,650 km) of life-bringing goodness. It flows, rather strangely, from south to north, winding through Egypt like a powerful snake and spitting out in the Mediterranean. That’s why, even though we Theban ladies are in the southern part of the empire, it’s called Upper Egypt, while the northern part is called Lower Egypt. The Nile dictates every aspect of our lives, and how we see the world we live in.

The river floods every spring, called the inundation. When it recedes, it leaves a verdant strip of land that is the literal lifeblood of Egypt. The silt is so rich that farmers don’t have to do a whole lot more than toss some seeds out the window to end up with a rocking harvest. That harvest feeds a huge portion of the ancient world.

Much like they say that everything in Australia is big, has teeth, and can kill you, everything along the Nile River is larger than life: think giant palm fronds, date and banana trees, swaying papyrus, and giant hippos, which I just found out have webbed toes: who knew? You’ll also find 18-foot crocodiles. *Shiver.* This river’s powerful enough to conjure miracles: they say it has just half the boiling point of other waters. It’s seen as a giver and nurturer of life: which is why Hapi, though he is the male god of the Nile, is often pictured with breasts. He and his river are seen as fertile, too. As such, its waters are sometimes given as a wedding present to ensure the bride is quick to conceive.

That’s why Egypt is called Red Land and Black Land: Kemet (black) after the fertile silt and Deshret (Red) after the desert surrounding it: the Nile is what makes this whole world go round.

And in this world, we have three social classes: the small sliver that is the royals and the noble families surrounding them; the large wedge of free working people, and a smaller chunk claimed by slaves and serfs. As with everywhere we’re likely to travel, your day to day life is going to depend entirely on what class you find yourself in. As such, we’re going to weave the paths of two different women together: a wealthy noblewoman and a working-class farm gal.

Stretch your limbs, ladies: it’s time to start our day.

GETTING READY FOR GREATNESS

We’ll awake in a bedroom: both of our ladies live in houses that are basically the same in terms of structure. Though your bed is not quite what you’re used to, time traveler: it’s got a wooden frame and springs of woven cord or leather strips, kind of like that poolside lounger at the public pool – the one with the crisscrossing straps. There’s no headboard, but there is a footboard to keep you from sliding off as you slumber. You’ll get snuggly with some linen sheets, but no pillow: instead, you’ll use a wooden headrest. It’s in the shape of a sideways H, with a solid base and a gently sloping piece to rest your head and neck on. Which, to me, looks like a torture device, but apparently it protects us from evil spirits while we sleep, so...let’s roll with it. Grab that oil lamp from the alcove by your bed – our windows are small to keep out the heat from that scorching desert sun, and it’s dark up in here – let’s head off for a morning pee.

This is what ancient Egyptians used instead of a pillow. Does this look like a comfortable place to rest your head? Yeah, well…at least it wards off evil spirits. And it’s probably good for your posture.

Courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum of Art

The house we’re standing in is a marvel. It’s not one of Egypt’s temples, palaces and pyramids, made of stone and still standing in our century. These houses have mostly been lost to time. But still, long, LONG before air conditioning and indoor heating, our ingenious architects have come up with something that suits the desert’s wild swings in temperature and works for every situation and budget: a rectangular structure made out of adobe, which comes from an Egyptian word that sounds a lot like it, made of Nile mud and straw or sand. It’ll have a door at one of its narrow ends, preferably facing north to catch the breeze, and be separated into three sections: a garden area out front with a central pool to keep the garden from dying, then a kind of open-air front porch surrounded by columns to provide shade for family get togethers. Behind that are the rooms we wash up and sleep in. How fancy this structure is depends entirely on how much money we have. Since we’re in Thebes, our house might be upward of three stories tall, connected to the ones beside it like modern-day row houses. Palaces and temples are another ball of wax, but we’ll talk about those later. We still haven’t peed.

As wealthy women, we’ll have a latrine wall built into our house featuring a toilet seat, sometimes made of limestone, with some kind of reservoir underneath, but no real plumbing system. Our farm gal will probably have a wooden stool with a hole in it, and beneath that, a bowl filled with sand. So, we’ve got a fancy litterbox situation. FYI: we will be pooping this way until someone invents the flushing toilet many, many centuries from now. I don’t know what we’re using to wipe, but it’s not likely to be toilet paper. So I hope you brought some Wet Wipes with you.

Now it’s time to scrub down. Because if there’s one thing we Egyptians are serious about, no matter what class we’re in, it’s cleanliness. While our 19th-century Victorian friends from Season 1 are concerned that bathing too much is going to make you sick, we Egyptian ladies are concerned that bathing too little is going to be the death of us. Plus, being clean brings us closer to the gods. Even when you’re dead, cleanliness matters: Spell 125 in the Book of the Dead says that you can’t speak to anyone of import in the afterlife if you aren't “clean, dressed in fresh clothes, shod in white sandals, painted with eye-paint, anointed with the finest oil of myrrh.”

This is convenient, as living in a sticky-hot desert tends to make one want to bathe multiple times a day. The Egyptians do it upwards of four times, when they can. Often this isn’t a full-body dunk occasion: especially for us farm girls, we’ll be rinsing our hands, faces, and feet in basins specially made for this purpose. Full baths tend to be a public affair had in bathhouses, not at-home soak fests. If we’re really rolling in dollars, we might even have ourselves a “shower”: aka, a servant artfully pouring jugs of water over us. Hey: don’t knock it ’til you’ve tried it! The water will go down a drain to be collected in a jar somewhere, then used to water the garden.

We often mix natron into our bathing water, a natural salt not unlike bicarb soda, which is also used to preserve dead bodies in the mummification process. So, multi-purpose! If we can’t afford that, we’ll scrub ourselves with an ash- and clay-based soap, or oils mixed with salt to treat skin issues. After that, we’ll slap on some deodorant that includes, say, turpentine and incense, and get to plucking.

A hairy Egyptian body is not a happy body. That includes most facial hair, and if tomb paintings are anything to go by, we’re not big fans of bushy eyebrows either. Our outfits are not going to leave a whole lot to the imagination, it’s hella hot out, and lice are a fairly common complaint. So thank the gods for razors and tweezers! If you're confused about which implement is which on your dressing table, here’s a tip: the razor is the thing that looks like a scalpel, and the tweezers look the same as the ones sitting in your bathroom drawer back home. They were made of copper back in the Old Kingdom, but now bronze is the metal of choice.

Small bronze tweezers with rounded head from tomb E'05 7 at Esna. They look pretty familiar, no? Courtesy of the National Museums in Liverpool.

Now it’s time to brush our teeth. Yes, for realsies! Though their brushes are probably more like sticks with rags on the end, and their toothpaste probably leaves something to be desired in modern eyes. We don’t know exactly what they used, but one recipe and how-to-brush guide dating back to the 4th century CE involves mixing precise amounts of rock salt, mint, dried iris flower and pepper grains for a “powder for white and perfect teeth.” Sounds like a recipe for bleeding gums, but I mean, better than nothing!

For those wanting to keep fresh throughout the day, there are perfumes: a lot of them. During the Ptolemaic period, when Cleopatra’s having her decades in the spotlight, some quarter of her city of Alexandria is dedicated to making perfume, and pots to keep it in. Since we haven’t yet mastered alcohol distillation, these aren’t like the perfumes in our century: to make them, we’re soaking fragrant things in oil or fat, kind of like you’d make a chili-infused olive oil, then straining it through a cloth into a cute little jar.

Its contents depend on what we can afford. Cedar oil is a popular favorite – it’s still a favorite in our century. Have you ever walked through a cedar pine forest? Sweet gods, it is the best smell in the world. Syrian balsam and oil of Libya are also luxe options. Other ingredients include iris root, cinnamon, cardamom, myrrh, honey, even wine and flowers from the henna bush. The Egyptians sure know how to create a diverse and potent smellscape.

And now, gentleman time travelers, this is where you buck up, because we’re about to talk about periods. Though truth be told, things are hazy regarding exactly how we’ll be dealing with our time of the month. We suspect a couple of supplies are used: papyrus wrapped in cloth may have made a handy tampon, or a cloth tied to some kind of belt. There’s a passage in one historical text about how unfortunate a laundry man was because of how many menstrual pads he had to deal with. Though our blood is not always considered a bad thing. It’s considered to have magical properties, and is used for several kinds of medicine. Suffering from saggy breasts? Smear some on and things should perk up a bit! Mmmm…maybe later.

Now let’s put on a little cream to protect us from the sun, then sit down to apply our makeup. Don’t tune out for this part, male time travelers: Egyptian dudes are more into this stuff than anyone. I can’t imagine that, as farm girls, we’re piling it on, as we’re probably just going to sweat it off as we go about our business, but as wealthy women, this is an absolute must-do. So let’s gather our cute collections of little glazed jars, gaze into our mirror—a highly polished metal one, the word for which translates to “see-face”—and get to glamming.

Men and women alike are big fans of makeup, most particularly that dramatic cat-eye look this civilization is famous for. Take one look at the famous bust of Nefertiti and you’ll know why we're so keen to get the look. It isn’t just about beauty: your eyeliner reduces the glare of the sun, repels flies, AND looks damn good. A win all around! Originally our eyeliner was green, a color thought to enhance health, and made of ground malachite, which is also prescribed for medical problems related to the pubic area. And guess what? Modern science tells us that malachite does indeed kill several kinds of infectious bacteria. The ancient Egyptians know their stuff.

In the New Kingdom, it’s a black eyeliner called kohl that’s all the rage. It’s made of ground galena, mixed with some fat into a paste. We’ll apply it with a wood, bone, or ivory applicator stick, drawing it carefully around our eyes and all the way up to our temples. “Subtlety” is not a thing. This is not a look for the beginner makeup artist, so luckily us well-to-do women will employ manicurists and makeup artists, whose title translates literally as “painter of her mouth.”

We’ll put on some lipstick and rouge, probably a mix of red ochre mixed with fat, and use henna to dye our nails all fancy. If you’ve been paying attention, you’re probably wondering how you’re going to get all that fat off your face later: our makeup remover is powdered limestone mixed with vegetable oils. Scratchy, but effective. We’ll have many pots and applicator brushes on our table: we might even keep them in a little carrying case. We’ll have combs and special spoons, too, for mixing and sprinkling.

Queens and commoners both seek the help of hairdressers, when they can afford one. We Egyptian ladies aren’t just settling for our natural mop of what is likely to be jet-black hair, though we are quite vain about it. For those going bald or with greying hair, we have many remedies, which usually involve some mixture of blood, fat, and oil. We like our hair long, with a sharp, blunt cut. But we might also cut it in horizontal rows, or weave in some curls and braids just for funsies. It will be greased into submission with beeswax. So, your lover might not want to run their fingers through your hair.

Wigmakers also enjoy a brisk trade. Why? Because wigs are in, friends, particularly in the New Kingdom. A lot of people, particularly men and priests, shave their heads altogether because it’s cleaner: can’t get lice when you have no hair! And where we are, lice is a no-joke problem. But we’re not going to walk around like that. So after taking all that body hair off, let’s add some back on, shall we?

you seriously thought this was my natural hair?

This image comes from queen Hetephreses’s fabulous tomb. Courtesy of kairoinfo4u on Flickr.

As a wealthier woman, we’ll wear wigs to most social functions, whether we have a full and glorious head of natural hair or not. Hair on hair, baby! Unlike our century’s “it’ll look just like yours” hair extensions, we’re not in the business of making our wigs look natural: we WANT people to know we’re wearing them, as they’re expensive and make us seem more fabulous. We might even layer on a few: one short, one long. Move over, Queen Elizabeth the First: we’re about to outwig you.

We’ll adorn them with ribbons, sometimes made of leather or gold, tied around our heads. These can get quite fancy: golden flower crowns and diadems thick with jewels of the kind we picture Cleopatra wearing. Although you’d better not wear the SAME one Cleopatra is wearing...she will cut you.

Before we get dressed, let’s put on some jewelry. Men and women alike are piling them on, from rings and bracelets to broaches and necklaces. These adornments are made with gold, shell, bone, jasper, turquoise, lapis lazuli. Subtlety is NOT our style.

If we’re very fancy, we might even wear a kind of jeweled collar, which can get so heavy that we need a counterweight to dangle down our backs to keep from falling over. Though we’re not fans of the Hyksos, who invaded and ruled here in the 17th Dynasty, we’re pretty glad they introduced us to earrings. We’re even enjoying a form of ancient plugs.

But no matter who you are and how much bling you can afford, you’re very likely to have at least one piece of jewelry: an amulet dangling around your neck.

They can be made of stone, metals like silver or gold, or wood and bone if you don’t have a lot of cash on hand. The most popular are made of a ceramic called faience: a paste of ground quartz and water shaped into whatever figurine your heart desires, fired in a kiln, and covered with a colorful glaze. Many are made using a mold, making them one of the world’s first mass-produced items: amulet makers can turn out thousands from just one mold, and they’re crazy popular. Why? Because they call out to the gods.

The Egyptian name for them is meket, or “protector,” and they take the form of different gods whose intervention you might want in your affairs. A cat eye invokes the goddess Bastet, the slinky cat in charge of the home, fertility, and women’s secrets. If you’re pregnant, you might wear Tauret, a pregnant hippo goddess who protects expectant mothers.

Let’s sit in the nude with just our jewels on for a minute and ponder Egyptian religion, because it lives at the very heart of life here. This polytheistic system explains and controls everything around us: how well crops grow, the flow of the Nile, the rising of the sun and the moon. Nothing happens unless the gods will it. There is no separation of church and state here. The gods are everywhere, in everything, always watching, and Egypt’s prosperity and wellbeing depend on them above all else.

Bastet, or Bast, the cat goddess of domesticity, women’s secrets, fertility, childbirth and (of course) cats. She protects the home from evil spirits and disease. So, not a lady you want to make angry.

Courtesy of the British Museum.

PLEASING THE GODS: A FULL-TIME JOB

We’ve got 2,000 or so deities to worship. A large number of those are female. This is key to understanding a woman’s place in ancient Egypt, and why we’re better off here in terms of rights than almost anywhere else.

Here’s how we see it. The gods represent a complete duality of male and female: both sexes are represented in the Egyptian pantheon, and both are crucial for keeping everything in balance. Maat, the deity in charge of balance and order, is a woman. And maat is key to Egypt’s continued success.

In the beginning, the world was just infinite dark and directionless waters. Shortly after the creation of the world, the stories say, the god Geb (the earth) and the goddess Nut (the sky) got sexy together – note that the male god is the fertile ground here, while the lady is the one carrying the thunderbolts. Together they created four important children: two gods – Seth, the lord of disorder, and Osiris, his opposite; and two goddess’ – Nephthys and Isis. These brothers and sisters go on to marry each other, setting a precedent for a whole lot of royal Egyptian incest. But they also showcase how true balance can only be achieved when man and woman work together, and that women have an equally important role to play.

And we understand that role can be violent. Take this little story about Egypt’s first pharaoh, the god Ra. He was so good at his job that the people grew lazy. So to punish them, Ra sent a bloodthirsty lion-headed goddess named Sekhmet to terrorize them all. That she did, eating thousands of people, earning cute nicknames like “Lady of Slaughter” and “She Who Mauls.”

And in the end, Ra couldn’t reign her in. Whoops! So he and the other gods came up with a plan: they spilled some red-dyed beer on the floor and she drank it, thinking it was blood, got drunk, and passed out. When she awoke, she snapped out of her crazed bloodlusty mood and Ra changed her into Hathor, the goddess of love and sexuality. A woman transformed from a power-hungry lioness to a loving, joyful cow. Yes, a cow. But this dual goddess shows us that women can be powerful warriors AND maternal figures; destroyers and nurturers. As the Insinger Papyrus has it: “It is [because of] women that both good and bad fortune are on Earth.” And that gives us power.

But more on that later. First, let’s get dressed.

TURN TO THE LEFT: FASHION!

We'll be dressing, above all, to keep cool. We won’t have breathable cotton until the Romans show up, so the thing to wear is linen, most often spun by women weavers. The whiter it is, the better: for most of Egypt’s history, white is the #1 color of choice. Which impresses me, because I’m notoriously bad at keeping my whites looking nice. White t-shirts are my enemy. When our white linen starts getting dingy, we might lay it out in the sun to bleach: we have no actual bleach in this era, a fact for which the Nile is probably grateful. But as 18th Dynasty ladies, we might throw some colorful linen into the mix as well. Particularly if we can’t afford fine fabrics: nothing hides a cheap weave like dying it blue, amiright?

The most common outfit is a sheath held up by shoulder straps: we’re talking a long, narrow dress that begins at the ankles and rises up to just under the breasts. You’ll top it off with a contrasting strip of material, wide straps or a sash to cover your lady orbs. You might wear two long rectangles that form a skirt-and-shawl ensemble, or a long sack you can just slide right into and belt at the waist for some flair. Our gentleman friends are wearing kilts: very breathable. But really, men and women’s outfits aren’t all that different. When the nights get cool, there is wool to layer over.

But are we wearing undies under there? Probably not. King Tut, he of the famous blue-and-gold sarcophagus, will be buried with many sets of loincloths, so it’s possible that men are wearing mankinis under their outfits. But we’re probably wearing nothing at all.

If tomb paintings are anything to go by, our clothes are fairly form fitting and semitransparent. We Egyptians are not concerned about walking around semi-nude. And bodies are often portrayed as thin and waifish; try finding a tomb painting where everyone isn’t as svelte as a Calvin Klein model. You’ll have to look hard. Does this mean everyone was trim and slim in ancient Egypt, as some people claim? To me, that seems pretty suspect. Tomb paintings represent how people want their afterlife to go: it’s their aspirational Pinterest board, not necessarily their stark reality. Put it this way: if some alien race came down and judged our physiques on the last 50 years of magazines and adverts, do you think they’d get an accurate picture? You’re lovely, Kate Moss, but you aren't exactly repping my body type.

no clothes? no problem.

From Tomb of Nakht, Wikicommons

Our outfits were pretty form fitting in the Old Kingdom, but in the New Kingdom we’re doing a lot more folding to create a layered, drapey look. The wealthy wear a fine sort of dress for banquets, almost like a sari: it’s basically a rectangle four times as long as it is wide, which can be wrapped around you in all sorts of arrangements. Men and women are both fond of this outfit, as it’s comfortable and looks banging on many different body types. Hopefully you’ll have some attendants to help you, because the possibility of a nip slip is ever present if you wrap it wrong.

Unlike commoners, queens often wear colorful, embroidered linen, particularly from the New Kingdom period on. Beads are a common feature. “Nets” of them are often worn over the queen’s head and neck, a la that fancy Cleopatra Halloween costume. We might even make a whole dress out of faiance beads, strung together into a long, columnar gown that any 1920s flapper would kill for. I’ve posted one in the show notes for you, which I think Nicole Kidman should wear to the Oscars.

Seriously: could this beaddress get any better? I’m not exactly sure what you’d wear underneath it…maybe nothing? That’s bold.

This Old Kingdom beauty is the earliest surviving example

of the style, painstakingly reassembled from approximately 7,000 beads found in an undisturbed burial of a lady. The strings had disintegrated, but the few beads remaining stay lay in their original pattern. The beads were originally blue and blue green in imitation of lapis lazuli and turquoise.

Courtesy of Harvard University, Boston Museum of Fine Arts Expedition.

Hair décor aside, hats aren’t popular. Which is funny, considering how punishing the sun here is. Perhaps it’s because the pharaoh and his royal wife wear tall hats as a sign of their status, and wearing one would be like wearing a white dress to someone else’s wedding.

Egyptians dye leather to wear as belts and make into thong-style sandals: that’s how far back in time that pair of plastic sandals you last wore to the beach goes. They’re often made of leather and rushes, which’ll need padding, held in place with an ankle strap. I don't know about you, but I’m feeling pretty sexy!

As you head to your living quarters, grab your saluki, a greyhound-like dog. We Egyptians are the first people on record to domesticate them. Check up on your cats, too: we’ve domesticated them for hunting, but they’re regal and strong, and have taken up a special place in our hearts. Monkeys are also popular pets, so if you have one, make sure to feed him. Nobody likes a hangry monkey.

let’s slip into our golden shoes and go about our business.

Gold sandles ca. 1479–1425 B.C., which probably weren’t meant for everyday wear. Courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

OUT AND ABOUT

While women’s work isn’t confined to the home in ancient Egypt, the most common title we’re likely to hold is “Lady of the House.” This job involves running the household and bearing children; most of us will be defined, first and foremost, as wives and mothers. There’s a love poem that speaks to the ideal Egyptian female:

Of surpassing radiance and luminous skin,

With lovely, clear-gazing eyes,

Her lips speak sweetly

With not a word too much.

That’s not to say that Egyptian women are expected to be quiet and stay at home. Some women choose alternative career paths, and they have more freedom to pursue them here than anywhere else in the ancient world. Many visitors are shocked by it.

Take Herodotus, our Greek historian friend, who shows up in Egypt, walks around, and is like, wait... whaaaaaaaat? “The Egyptians themselves in their manners and customs seem to have reversed the ordinary practices of mankind,” he wrote. “For instance, women attend market and are employed in trade, while men stay at home and do the weaving....Men in Egypt carry loads on their heads, women on their shoulders; women pass water standing up, men sitting down.” He’s probably exaggerating a bit on that last one...and what are you doing watching women pee anyway, ya creeper? – but his shock makes sense. As we’ll find out when we travel to ancient Greece, this is a VERY different world than he’s used to.

For example, let’s talk a little bit about love and dating in ancient Egypt. Unlike in many other ancient societies, women are very visible in the public sphere, and that gives them freedom to mix and mingle with potential partners. Let’s say at the market we spy Tom Hiddleston, who has obviously come back in time with us. Damn, he looks amazing in eyeliner. Sorry: focus. Our eyes meet: of course it’s instant connection. And unlike in, say, Greece or Rome, love is actually valued in a marriage, so this is considered a very good thing. He probably won’t come at us directly, but will go and talk to not our father, but our mother or sister, asking them to plead his case. He might even write us some love poetry, like this one:

To hear your voice is pomegranate wine to me:

I draw life from hearing it.

Could I see you with every glance,

It would be better for me

Than to eat or to drink.

You had me at pomegranate wine, Tom! But let’s say I’m a shy and uncertain recipient of Tom’s affection. There is plenty of magic floating around in ancient Egypt, and some of it is handy when it comes to getting a woman into bed. One such spell says that Tom should make a scented oil mix, then add in a black mesh fish to marinate. As it does, he’ll need to say a specific incantation every time I have contact with another man. Eventually, he’ll take his fish-infused oil and rub it on his manly member, rendering him irresistible. Sounds…pungent.

Let’s reverse the situation. What if there are other girls vying for his attention? I could always purchase a love potion to aid in my cause. Or I could just curse my rival, if I’m feeling particularly mean about it. We happen to have a recipe that promises “to make the hair of a rival fall out, anoint her head with burnt lotus leaves boiled in ben-oil.” Damn.

Most Egyptians are getting married when boys are around the age of 15 and girls are about 12. I mean, when your average life span only goes up to 40, you’re keen to get such things underway ASAP. Side note: Premarital sex doesn’t seem to be SO big a worry, and virginity doesn’t seem to have been required of a wife. But cheating on your husband - no no, girl. That'll get you fed to the crocs.

Interestingly, there's no word in Egyptian for wedding: it isn’t a religious ceremony, but a legal one, which is agreed upon either by written contract or an oral agreement. Shout your love for each other over the fence, and we’re golden! Move in and make house together: that’s enough to show the world that you’re wed.

A lot of these weddings are arranged to be financially advantageous, but not always. Regardless, the bride and groom sign something that’s almost like a prenup. Whatever we bring into a marriage as our dowry is ours, no matter what: and if Tom dies, and let's hope he doesn't, we're entitled to at least a third of his property—sometimes even more. We’ll exchange wedding gifts and agree on a subsidy to be paid to Tom’s parents to help cover the cost of our upkeep, and our parents will make stipulations about how Tom must treat us in return.

And what are the rules with such treatment? Let’s ask Ptahotep, an Old Kingdom advice columnist:

“If you are a man of standing, you should establish your household and love your wife at home, as is proper. Fill her belly and clothe her back; ointment is the prescription for her body. Make her heart glad as long as you live—she is a profitable field for her lord. You should not judge her, or let her gain control…Let her heart be soothed through what may accrue to you; it means keeping her long in your house.”

So: keep your wife happy, and it’ll pay off for you; don’t be too harsh, but don’t let her boss you. And then there’s this other advice giver’s gem, which I think us modern ladies will jive with: “Do not supervise your wife in her house if you know that she is capable; don’t say to her, ‘where is it? Get it for us!’ when she has already put it in the most useful place. Watch and be silent, so that you may recognize her talents.” Yeah: stop moving the crock pot, TOM! And how’s this: we can divorce and marry again without much issue. All we have to do is move out, and it’s done. Whaaaat?

As free ladies, regardless of our status, we have two fundamental rights: the right to travel where we want and the right to enter into contracts. Our place in the grand scheme of things is defined way more by our social status than by sex. We have full equality under the law: we can own property and sell it, borrow money, serve as witnesses in court, and be punished for our crimes in the same way as a man is.We have evidence that women often receive equal pay rations for doing the same job as men, and women’s wills deciding which child will inherit. One woman named Tay-hetem even loaned her husband some money in one written contract: 3 deben in silver, at a steep 30% interest. Damn, Tay. That’s worse than my student loans!

Keep in mind that this is not a lady utopia. Our society is definitely still patriarchal, but descent and kinship runs through women: royal Egyptian princesses aren’t sent abroad to marry foreign kings, because it would give them a right to the throne. The seed of divine kingship runs through women.

How did this happen, when none of the empires around us gave women nearly so much favor? A lot of it goes back to the gods. Remember that balance and order, or ma’at, is everything: it keeps our world turning, and we Egyptians love nothing quite so much as an efficiently turning wheel. We also love the gods, and they clearly value their women. But more than that, women are mothers: they give rise to life, to prosperity, and to little men. And that gives her a real kind of power.

To illustrate this thinking in action, let’s dive into the violent love story of two gods: Osiris and his sister Isis. With the help of his smart wife, Osiris became king of all Egypt. But the royal couple weren’t psyched about our wild and heathen ways, so they gave us agriculture, wheat and barley, poetry and art. Things were looking rosy.

But Set, their brother, wasn’t having it. So he chopped his brother Osiris into 14 pieces and threw him into the Nile for the crocs. He didn’t count on the intrepid Isis going on a hunt to find him, gathering up all of his man meat pieces so she could magic him back together again. But there was a problem. She couldn’t find his magic man stick: apparently it was eaten by a fish. No matter: she waved her hands, said, “I’m about to do some sexy sorcery,” and made her hubby a new one out of gold. She then magically resurrects Osiris for one last roll in the hay. GET IT, ISIS!

Statuette of Isis and Horus, 332–30 BCE. Being the mother of kings makes you a very powerful woman. It’s from you that the divine seed flows!

Courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

The product of that union, Horus, went on to become a ruler of men. His symbol, the hawk, is synonymous with kingship. And Isis? She’s famous not only for her sexy sorcery, but for being the mother of kings: all kings. It’s from her that kingly divinity flows.

She’s one of the most popular and beloved of all the goddesses: mother, devoted wife, and sexy witch lady. She’ll even make her way outside of Egypt’s borders, becoming a cult figure in ancient Rome. No divine woman will trump her popularity until we get to the Virgin Mary. Which all goes to show – not just the trials of having a golden penis, but that divine power is woman born. And for us ladies, that makes all the difference.

PART 2

YOU BETTER WORK

Last time, we left off talking about where Egyptian women got so much legal power from.

So what are we doing with our days, work wise? As a farm gal, we’re likely very busy preparing meals, brewing beer, looking after the kids, and cleaning. But we won’t be doing laundry: apparently that’s a man’s job. YAS, honey! A few hot tips from ye old Egyptian papyrus scrolls: natron, which we bathed with, is very good for cleaning; the fat of an oriole is good for getting rid of flies, and cat fat helps clear the house of mice. I’d have thought a living cat might be better, but you do you. We’ll be working out in the fields during harvest time, so keep your eye out for crocodiles.

Some women step in to manage their husband's affairs when he’s away, making sure the farm keeps running and working the account book. Regardless, it ain’t an easy life. No one’s going to fan you with palm fronds and hand you lemonade when you get tired.

For the huge Egyptian work force, there is no eight-hour work day, and much like Dame Maggie Smith in Downton Abbey, we are not familiar with the term “weekend.” Some credit the Egyptians with giving us the 365-day calendar: 360 of those days are for work, with 5 left over for religious festivals. A brutal schedule that America is still more or less clinging to.

The higher class we are, the more likely we are to venture into other occupations. And unlike women in 19th century America, women are well accounted for in the public sphere. The top five jobs for women are: priestess, midwife, professional mourner, dancer, and musician.

The pharaoh – which actually doesn’t translate as “king,” but “a great house” – is at the very tippy top of the power pyramid. He – or sometimes She – is a direct descendent of the gods: the living link between the gods and man. He protects the people, makes sure the Nile floods, brings the sun up in the morning and the moon at night. He is our chief priest, always, but there are a LOT of gods to honor, temples to maintain, and rituals to stage, and he has a country to see to. That’s where the priestly class comes in.

We regular people are very involved with the gods, but we’re not going to church to pray to them. Such places are reserved for priests. These positions are often privileged, lucrative, and powerful. But we’ll find women here, too, serving as priestesses. And unlike in other places, you need not be a virgin to apply.

Temples are considered the gods’ actual houses, and their statues are treated like the living deity: he or she is invited into their statue every morning. When they wake up, they’ve given breakfast, fed regular meals and prayers throughout the day. All of their needs are taken care of: even sexual ones. Take the god Amun. Every day, his High Priestess has the task of exciting her lord with dance and song and…who knows what else, to be honest. These statues, by the way, are often carved with an erection. How does one satisfy a giant statue? Your guess is as good as mine.

Here we see Nun, god of the waters of chaos, lifting the barque (or boat) of the sun god Ra, represented by the scarab and the sun disk, into the sky at the beginning of time. During high holidays, ancient priests have to put their god’s giant statue in a boat and row it across the Nile, which sounds…tiring.

Wikicommons.

But the gods don’t always stay in their temples, hidden away from prying eyes. On festival days, they are put onto barques, or long barges, and taken across the Nile to special locations for celebration and worship. I dread having to move my bed when I move houses: imagine trying to move a huge marble Isis. Girl, get up and walk yourself!

Priestesses are close to the gods, which gives them proximity to the pharaoh. They can also read and write. Egyptians have a beautiful written language in the form of hieroglyphs. They basically invent paper, made by smashing layers of papyrus flat and stitching them together into long scrolls. Papyrus is where we get the word “paper” from, so, you know: kind of a major invention. Writing is considered a sacred art: if you write something down, it’s more likely to happen. Young men are pushed to learn to write, as that will give them a chance to become official scribes.

Most people can’t write: some estimates have it at 2% of the population. It doesn’t seem as if many of those are women. We know that the wives of artisans and men of learning write letters back and forth with their husbands, but other than some royal women, not many become official scribes. But there are exceptions: probably more than we’re aware of.

After all, there is a goddess of scribes: her name is Seshet. She’s usually to be found wearing leopard skin and a seven-pointed star headdress, winning her Best Dressed Goddess of Egypt. She’s in charge of record keeping and the chief librarian at the Per-Ankh, or House of Life: a kind of library/university/publishing center where doctors and scribes go when they need to do some learning. And while they may not do it in huge numbers, we know that women roam its halls.

The Egyptians basically invented paper, like this ancient papyrus scroll, but not that many people could write in their beautiful hieroglyphics. From the Book of the Dead of the Priest of Horus, Imhotep (Imuthes), ca. 332–200 BCE. Courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Most doctors come from the priestly class and are men – but not all. The first Egyptian female physician of record is Merit-Ptah, who lived around 2700 BCE, toward the end of the Early Dynastic Period. An inscription on a tomb at Saqqara named her Chief Physician: so, she would have been supervising male underlings and attending to the king. Another early doctor named Peseshet lived around 2500 BCE, when the Great Pyramids were being built. Her title was 'Lady Overseer of Female Physicians' and may have taught future doctors at the temple-school at Sais. This is super progressive for the ancient world. When a 4th century Greek woman named Agnodice wants to study medicine, she has to smuggle herself into Alexandria to do it, then goes back home to tend to lady patients illegally. What a stone cold bad ass!

When it comes to delivering babies, it’s mostly women who serve as midwives and wet nurses. In the New Kingdom, where we’re currently residing, royal wet nurses have a lot of power: not surprising, given that they’re the ones nurturing tiny pharaohs. So much power that diplomatic men want to marry them just to get ahead in politics.

In several centuries, in Cleopatra’s sparkling city of Alexandria, we’ll see female lecturers take up residence among their male counterparts. We even see them take up high public offices, like treasurers, judges, and vizier (a kind of prime minister), which is one of the highest positions you can get after the pharaoh. And then, of course, there are our queens and female pharaohs. The Dynasty currently running the show will give us two of them. But we’ll hang with them a little later.

A little further down the working lady’s totem pole, we have weaving. Weaving textiles is a female-dominated profession, and often fully women-run. In our current time period, several ladies are overseeing a team of weavers at the Temple of Amun at Karnak. The royal harem has a stake in the industry too, training and supervising textile workers – and sometimes even joining in to do weaving of their own.

Another super fun and potentially lucrative job for women is being a professional mourner. The Egyptians make an epic deal out of funerals, the idea being that the more people you have wailing and moaning over the deceased, the more important they’re going to seem. Apparently overt and public grieving is primarily a woman’s business, so families of means pay women to make a show of grieving for the 70 days it takes to mummify a body. This will involve tearing your clothes, ripping at your cheeks, much wailing, and throwing dust over yourself: the more drama, the better. Somehow it sounds both painful and tiring.

Let’s get our wail on.

Lamenting Women from the tomb (TT55) of Ramose, Wikicommons

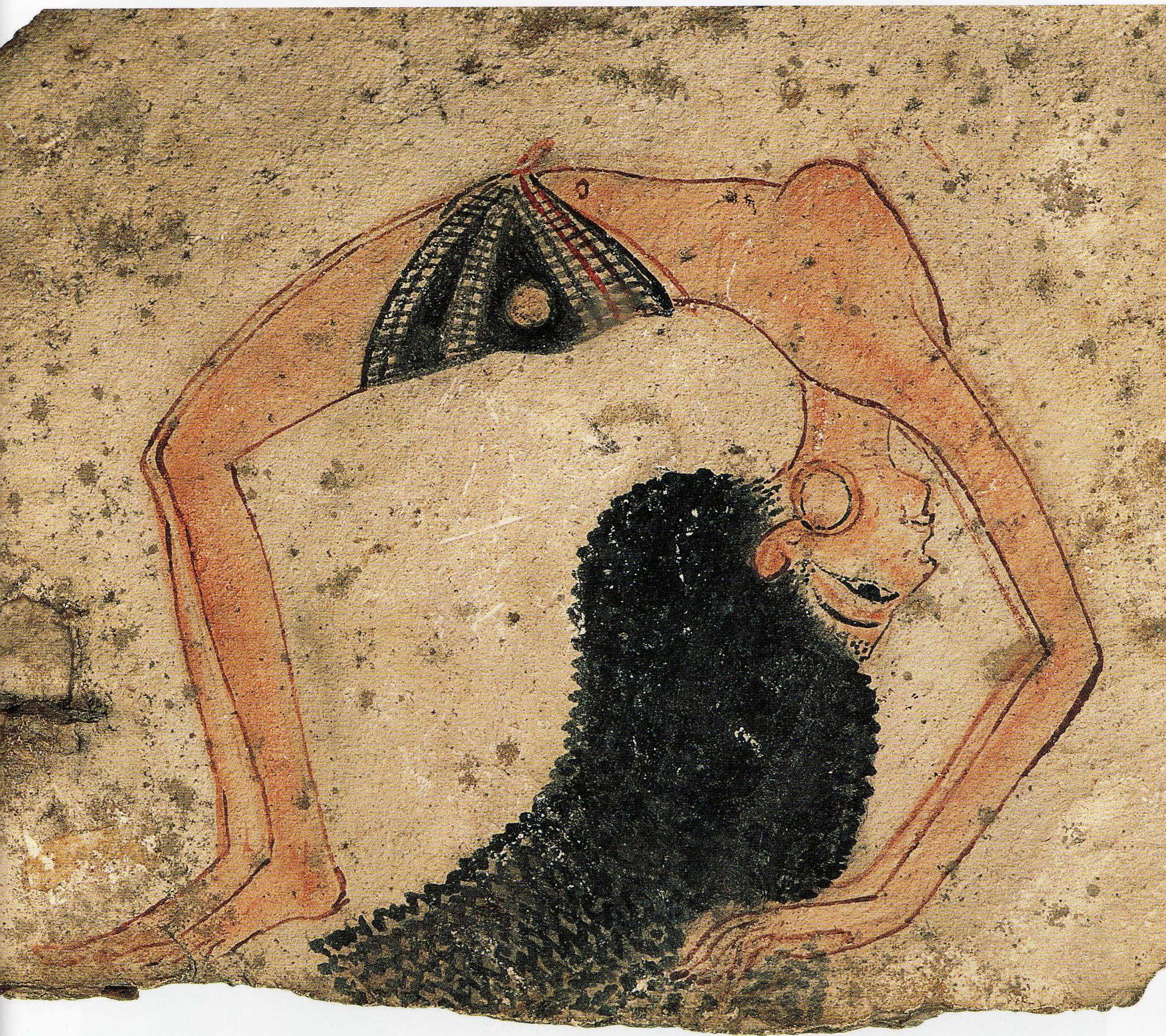

Women also serve as professional dancers and musicians. Some are employed at temples, doing special dances for the gods. Others are good enough at both singing and dancing to earn the title “ornament of the king.” Only women dance at banquets, which they do wearing the ancient Egyptian version of a thong, bending themselves into all sorts of twisty positions. This sounds a bit…concubiney, to be sure, but these women often have influence and take an active part in royal functions, state events, and religious ceremonies. Musicians are an important part of religious rituals and celebrations, playing everything from the lyre to the sistrum – a kind of ancient rattle – to welcome a god into his temple or a king into his hall.

Women are also doing manual labor outside of farming: One tomb painting shows a woman steering a cargo ship. When the man who brings her meals gets in her way, she shouts, rather gloriously, “Don't obstruct my face while I am putting to shore.” You tell him, lady!

For our work, we’ll be paid not in coins – we’ll have no monetary system until the Romans come calling – but rather in barter. Value is calculated in deben, or about 90 grams of copper, and everything is given and taken in trade. Oil, wheat, and barley are all popular things to trade for. A few bushels of wheat for that pair of golden earrings? Don’t mind if I DO.

WHAT WE DO FOR FUN

Of course, it’s not all work and no play in ancient Egypt. While their elaborate tombs and pyramids give the impression they’re obsessed with death, what they show us is a real zest for life. They fish, hunt, and sail: ancient Egyptians are keen water sports enthusiasts, fond of doing something that sounds a little like Olympic kayaking. As Seneca wrote, “The people embark on small boats, two to a boat, and one rows while the other bails out water. Then they are violently tossed about in the raging rapids. At length, they reach the narrowest channels…and, swept along by the whole force of the river, they control the rushing boat by hand and plunge head downward to the great terror of the onlookers.”

We play music for fun, using harps, reed pipes, drums: you name it. And we play some of the same games as in our century: for instance, that old Color Day favorite, tug of war. One tomb painting displays a bunch of guys mid tug, with the words “Your arm is stronger than his! Don’t give into him!” beside it. There’s also wrestling, juggling, and bowling, which Egypt invented...though it’s hard to say how many women are getting into it. Board games are particularly popular with everyone. Take senet, which features in many illustrations of royal women. We don’t know how it’s played, so I can’t advise you, but it looks a lot like GO, so just start moving pieces around until someone yells at you.

If we are an upper-class lady, we might pass the time with a stroll in carefully tended gardens. We might even go on a river cruise up the Nile. Though, as a rule, Egyptians don’t travel outside of their country’s borders just for funsies. You might die in a foreign land, and really, why leave when home’s got everything you need?

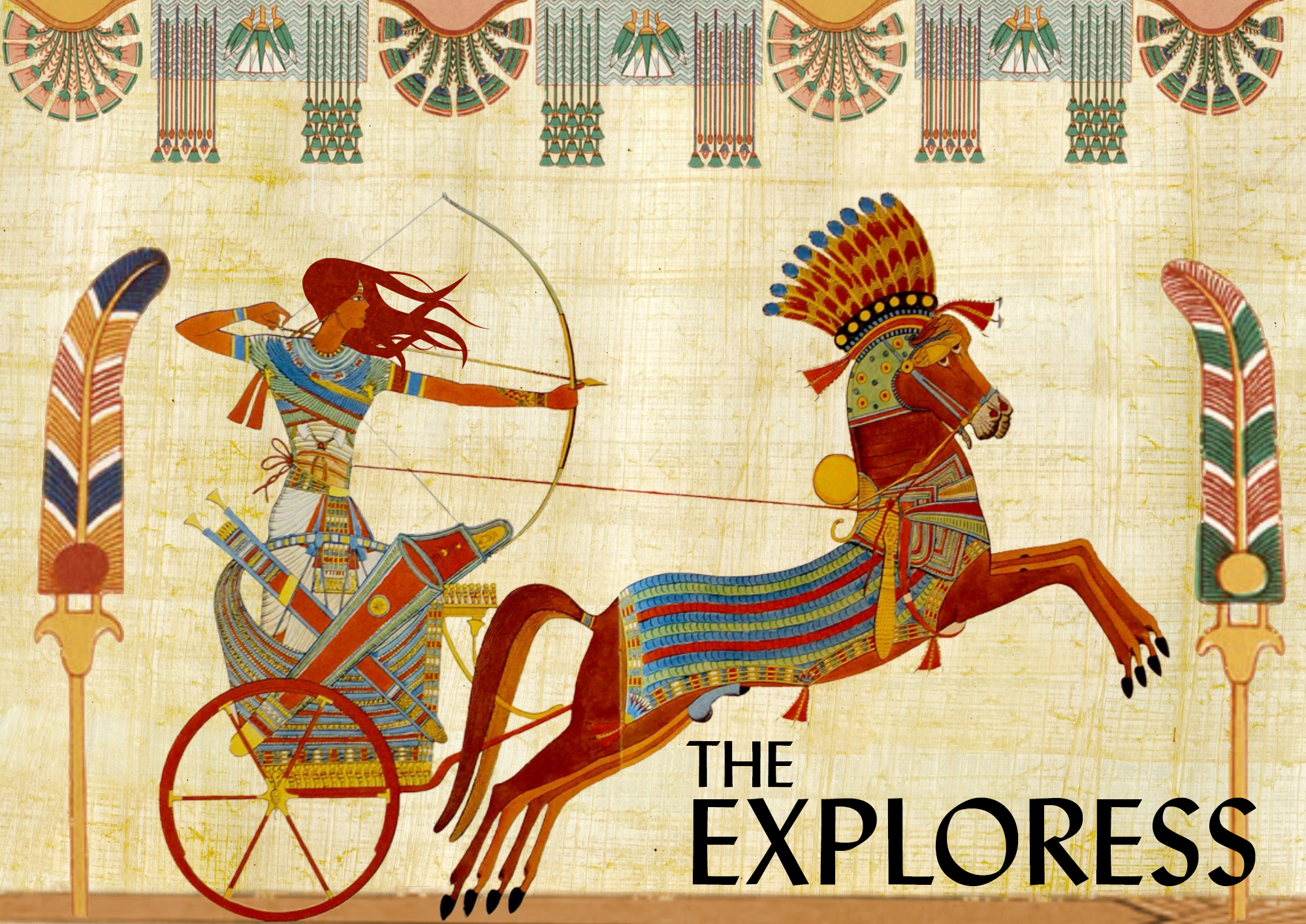

And then, of course, there are feasts. Ah, feasts. Let’s go to one! Lock your door behind you – we invented the door lock, so we might as well use it – and let’s head over to our friend’s place for dinner. As farm girls, we might walk or travel by river boat. As fancy ladies, we might get our servants to take us via carrying-chair. Or – my favorite – we might drive our own chariots, introduced to Egypt by the Hyksos not long ago. Mush, greyhounds!

FEASTING

So here we are, at a fancy feast in someone’s palace, wearing much gold and a see-through mesh bead dress. Owning it! Let’s soak in the majesty, shall we? We’re sitting on the floor around a long table, or we might be on low chairs or stools. There’s likely to be a little bowl to wash your hands in. And since we want to make sure we’re smelling our best, we might hold a lotus flower in one of our hands. You might even mix a little into your wine, though it’s mildly hallucinogenic, so I don’t recommend it. But we’ll also take things a step further in the perfume department by putting a cone of incense-infused fat on our heads. There it will warm and drip, releasing its scent throughout the evening. How we keep said fat out of our cat eye makeup, I’m not sure. The most popular incense for such occasions is frankincense, a resin from trees that grow only in Arabia and Somalia. There’s a reason a king will one day gift some to Jesus: it’s very valuable stuff. Pharaohs make special expeditions to a land called Punt, somewhere near present-day Ethiopia, to get it: myrrh, too. Dancers will probably come in, mostly naked; musicians might play, lightening the mood.

In Cleopatra’s day during the Ptolemaic era, things will get extra fancy. Floors covered in flowers, looking like an indoor meadow. Because, QUEEN. Rose flower crowns are made for every guest, sprinkled with cinnamon and balsam and cardamom. They keep us smelling fresh, and apparently their scent also keeps us from getting too drunk. Which is good, because we have a lot of alcoholic beverages to choose from.

The staples of our diet, no matter our class, are beer and bread, so you’d best not have a gluten allergy. They spring from the same process: once dough has been mixed and shaped into loaves, it‘s left to rise. If we want bread, we pop the pans into the oven, and if we want beer, we’ll crumble them into water, make a mash, and let it sit for a bit until it’s fermented. This is all wild yeast we’re using, so the final product is likely to be variable. Then we’ll strain the stuff into jars, and hello, beer! The Greeks and Romans look down on this tasty beverage, but we’re huge fans. Some claim the Egyptians invented it, but it’s more accurate to say that we invented the first beer we time travelers would recognize. And it’s irrevocably tied to the ladies, because brewing is considered a domestic activity: and that means brewing is a woman’s domain. In fact, the Egyptian god of beer is a woman: Tenenet. Take that, flannel-wearing modern-day male brewers!

It’s a staple of the working class: the guys who built the pyramids were paid for their labor in beer. Doctors dole it out as medicine, for its ability to confuse evil spirits and because of how it “gladdens the heart.” As farm gals, we’ll drink it every day, because something’s got to make our lives more bearable! Just kidding: it’s because the brewing process purifies our water, making it safe for us to drink, though we ancient ladies probably don’t understand it as such. Plus, it’s nutritious: we use lots of whole grains in the brewing process, and unlike today’s beer, it’s thick and cloudy. So we'll often drink it through long straws, sharing vessels with friends like you might with one of those giant fish bowl cocktails you’ll find on the glittery streets of New Orleans.

It’s drunk everywhere: farmhouses and palaces, during rituals and at great feasts. Well-to-do Egyptians think it’s a peasant drink, so they tend to reach for their sweet wines, which they make with the tried-and-true barefoot stomping method. And we LOVE it. According to one account, one female party-goer asked for “eighteen cups of wine, for my insides are as dry as straw.” King Tut’s tomb contained 26 jugs to see him through his afterlife.

We might add some date juice to sweeten it, or red dye if it’s a holiday. It’s usually around 3 or 4 percent alcohol, which is fairly sessionable. For festivals and rituals it’s more like 7%, so...take care. There’s a reason that Sekhmet, our lion-headed man eater goddess, is called The Lady of Drunkenness. As the scribe Ani wrote, “boast not that you can drink a jug of beer. You speak, and an unintelligible utterance issues from your mouth…you are found lying on the ground and you are like a child.” Too true, Ani. Happens to the best of us.

So what are we soaking up all this beer with? Bread, and bread: so much bread. It’s at every meal, stuffed into meat, served with sweet honey. In terms of protein, as wealthier ladies, we’re most likely to consume red meat fairly often: plus pork and lamb, which we’ve domesticated, along with things like oryx and gazelle. Mm: gamey! There are geese and ducks, too, and if we’re fancy, maybe peacock. The Nile provides plenty of fish for our feast, as well. You’ll have access to a range of lovely spices: coriander, rosemary, parsley and fenugreek, and salt of course, but no pepper: not until the Romans come a’calling.

This stela of the Steward Mentuwoser (ca. 1944 BCE) shows him at his funeral banquet. If the ancients were anxious about one thing, it was that they have enough to eat in their afterlife.

Courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum of Art

For the farm girl at home, a mainstay are legumes, and luckily we’re all eating plenty of veggies: onions, garlic, leeks, squash, cucumbers, celery, radishes. Lettuce is considered the go-to food if you want an aphrodisiac. In terms of dairy, there’ll be a bit of cheese thrown in, for good measure, and milk. So far, it’s sounding better than the Victorian-era diet! Grab a spoon, by all means, but if you’re looking for a fork, don’t bother. There are two-tined ones to spear meat with and cook with, but we won’t be using them for eating. Your fingers are plenty good enough, don’t you think?

If you’re in the mood for something sweet, there’s fruit – dates, grapes, melons, pomegranates – and honey. No sugar, I’m afraid, but that’s probably for the best. A tomb in Luxor offers up a recipe for a cake made with tiger nuts. We don’t have chocolate, but we DO have carob: that chocolate-like seed pod that, back in our century, you’ll find in your closest expensive health food shop. Egyptian carob pudding, anyone?

While intoxication may not be encouraged, the Egyptians REALLY know how to have a good time. It’s painted all over their tomb walls in bright, lively colors: the most common scene involves a mighty feast. And why not? When the average life span is 25 to 30, with 50 considered practically decrepit, we’d better may hay while the sun still shines.

Feeling a bit raw the morning after? Maybe it’s time to take one of your three-times-monthly purgatives, using castor oil to clean out our intestines. While we’re at it, let’s talk about what medicine might be available to you. And let’s talk about childbirth...and how we might be trying to keep pregnancy at bay.

ANCIENT MALADIES

Though the Egyptians know an awful lot about our bodies and how they work, for an ancient civilization, this life isn’t easy. Particularly on our teeth. Part of the problem are the stones we’re using to grind grains for bread, which has us eating more sand and grit than is good for us. It wears down tooth enamel, exposing the pulp of the tooth and making it vulnerable to infection. Eau de mouth decay is a major problem, so we’ve invented the world’s first breath mints, made from frankincense, myrrh, and cinnamon boiled with honey and shaped into pellets.

A couple of common diseases are schistosomiasis, which involves teeny tiny water-borne worms that get into your feet, crawl on up to your bladder and on to your rectum, and start laying eggs there. Don’t be alarmed if you start peeing blood: or be alarmed, I guess, and hurry back to the future for treatment. Tuberculosis and lung conditions are also fairly prevalent, given how much sand we’re breathing in.

You’d think we would have learned a lot from the practice of embalming, but apparently the guys getting us ready for the afterlife aren’t doctors, and don’t treat their work as a means of studying the body. Doctors have learned what they know from studying animals, which means that they still know very little about how internal organs work. Generally, we’ll be treated at home, but since many doctors are priests, we may have to venture to a temple. These doctors will do you a solid by attending to you with clean hands, and they’re likely to be a specialist in something. There are even proctologists, whose name translates to “shepherd of the anus.” Though to be fair, they’re dealing with more than your posterior: pretty much anything happening below your belly button.

We have two means of approaching medical concerns: clinical and magical. If you’ve got a crocodile bite, say, we’ll just sew the wound closed and then put raw meat over it. Clinical. But if we have a fever and don’t know the cause, we might assume the problem is demons and treat it with a magic spell. Crushed forehead? Let’s make a poultice of grease and ostrich egg and say a quick spell. We’ll see how that goes.

There are several specifically medical papyri floating around, and many of their suggested remedies are woman-specific. If Tom Hiddleston is keen to know if you’re going to be good at childbearing, we’ll sit over a bowl full of beer and dates and wait to see how many times we throw up from the fumes. Each time we puke equals a future child: of course. Or you could go ahead and stick an onion into your cervix area: if your breath smells like onions the next day, you’re good to go! For those of us already mothers, the Papyrus Ebers prescribes a potion with opium in it to stop a baby’s crying, which is likely to do the trick. For the woman in labor, let’s rub peppermint oil on your posterior! I’m not sure how exactly that’s going to help you, but you’re sure to smell great while you work on your breathing.

Most medicines involve some combination of milk, beer, oil, honey, fruit and spices. The Egyptians practice an early form of homeopathy: the idea that the loss of one thing can be fixed by adding in something like it. We know of several instances where small children ate skinned mice not long before death because of this principle – sounds scrumptious – because the Nile gives life, and these mice appear miraculously out of its mud every year when the water recedes. They’re full of life, so maybe they’ll be able to grant it. This applies in less depressing cases, too: for instance, a mandrake root looks pretty phallic, so it’s given to men with erectile disfunction. Never mind that eating too much of it might make you go insane.

The Edwin Smith Surgical Papyrus goes into quite a lot of detail about how to treat ailments ranging from a wound on the top of the eyebrow to things like tumors of the breast (hint: there is no cure for that one. It’s mostly there to keep doctors from being sued). There’s even a remedy called “How to Transform an Old Man Into a Youth”, which details how to make a wrinkle cream out of a fruit called hemayet. In an early form of promissory advertising, it assures us that “it has been shown effective millions of times.”

If you listened to last season’s bonus episode on female hysteria, which I recommend highly, you’ll remember that the Egyptians know all about it. This ladies-only disease that turns us into crazy balls of emotion comes from our womb’s tendency to go wondering. To fix it, you’ll coax it back into place by putting good-smelling things near your mouth or vagina, depending on which way the womb has wandered. The theory is that it’ll corral your lady palace back into its proper place and ease your crazy. We’ll give women smelling salts in the 19th century, working on this very same theory.

BIRTH CONTROL & OTHER LADY ISSUES

Let’s say things got a little wilder at last night’s banquet than you’d hoped. What are we doing about contraception? The Kahun Medical Papyrus has a few ideas, and none of them are going to fill you with joy.

You might pray to a particular deity for help in this arena. The crocodile is associated with abortion, the hippo with pregnancy, and wearing their amulets might help you along your chosen path. But for those not wanting to take any chances, there are treatments both magical and botanical. You might attach a cat’s liver to your left foot or enjoy a potion of mule kidney and eunuch’s urine. Good luck choking that one down. A spider’s egg attached with a deer hide before sunrise is like a 12-month subscription to the pill. Early diaphragms involve wool moistened with honey and oil. But a traditional mixture of salt, mouse poop, honey, and resin? I’m not so sure about that one.

For a morning-after pill, try white poplar, juniper berries, or silphium: this fennel-like plant’s dark seeds have the power to ease your bloated tummy, spice up a meal, perfume your body, AND prevent pregnancy if you drink its juice once a month. You can also soak a rag with it and...well, you know where that's gotta go.

Other things you might stick into your lady palace: a mixture of unripe acacia fruit, honey, colocynth (or bitter apple), and ground dates. Acacia ferments into lactic acid, which can actually act as a spermicide. We might even use crocodile poop to prevent pregnancy. A medical papyrus from 1850 BCE assures us that: “Crocodile dung mixed with honey and placed in the vagina of a woman prevents conception…” After mixing the faeces with fermented dough, we're supposed to sprinkle it on or inside to stop sperm in their tracks. How delightful! Some researchers think the alkaline nature of this ingredient could achieve that aim, while others think not. Me, I think it sounds like a recipe for a yeast infection.

croc dung: a wonderful contraceptive!

A page from the Book of the Dead of the Priest of Horus, Imhotep (Imuthes), ca. 332–200 BCE. Courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Regardless of whether you’re excited to get pregnant or trying not to, you’re in luck: the Egyptians have come up with the first urine-based pregnancy test. We’ll pee on two patches of emmer wheat and barley seeds over the course of several days, and: “If the barley grows, it means a male child. If the wheat grows, it means a female child. If both do not grow, she will not bear at all.” Modern tests suggest the results are fairly accurate: say, 70% accurate. Well alright, ancient Egypt.

We won’t be going to the temple to have our babies. Instead we’ll do it at home, relying on other women and midwives, and we’ll do it squatting, sitting in our own little birthing stool. It’ll be made of bricks, which is why Egyptians sometimes call giving birth “sitting on the bricks.” We’re likely to do a whole lot of praying during this time, as childbirth is dangerous, for us and our babies. Child mortality is high: maybe as high as 50%. This is the price of living in the ancient world.

DEATH AND THE AFTERLIFE

Of course, we can’t spend time in Ancient Egypt without talking about death. Or rather, our quest to keep the party going after we pass out of the mortal realm, which requires quite a bit of ritual doing. When we die, our family will ferry our body over the Nile. We might even hire female mourners to travel with us, weeping and wailing to show how much we’ll be missed.

Long before sarcophagi, we buried our dead in the sand, which dried out our bodies to create a natural mummy. But no one likes their loved ones eaten by jackals, so in 2700 BCE, a pharaoh named Zoser took a bunch of mastabas– adobe rectangles – and stacked them on top of each other to make a step pyramid: one of the first. After that, the push was on to create ever-higher pyramids to encase the dead in. They are the tallest structures in the ancient world, and won’t be bested in height until the Eiffel Tower. How they built the great pyramids at Giza is a bit of a mystery: Khufu’s 480-foot pyramid has two million blocks, all weighing some 60 tons, which workers had to lift and move into place. Woof. Regardless, they’re a perfect symbol for how seriously Egyptians take their afterlife. It isn’t heaven: it is essentially a different plane, just like Earth, except that it goes on forever. We Egyptians don’t need a heaven when our home is already so great.

In the beginning, only kings could reach it, but now everyone has a chance: if you can afford mummification, a funeral, and a set of funerary texts. We have three spirits: the akh (the immortality of the deceased) tends to start out trapped in the body, so text and paintings on tomb walls will help remind it where it needs to go. Your other two spirits, the ba (personality) and ka (life-force), will make camp closer to the corpse, so they’ll need supplies to keep them going. That’s why tombs are filled with the kinds of things you’ll need for a long-term glamping trip: food, drink, clothes, jewels, furniture, wives, servants, your favorite dogs. But they’re also filled with spells and stories, tales of your greatness and what you hope your afterlife will look like.

But to make it on the journey, we need to preserve our vessel: the body. It’s pretty ingenious, this way we’ve figured out of removing the organs from the body, all put in Coptic jars with some natron to dry out much like you’d use salt to shrivel a slug.

All wrapped up: a reconstructed body of ancient linen created in the 1940s, which gives you a picture of how Egyptian bodies stayed preserved for so long.

Gilded wax on a reconstructed body of ancient linen, 400–250 BCE. Courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

The heart stays in, as it’s considered important, but the embalmer doesn’t think much of your brain: that he’ll pull out your nose with a little hook. *shiver*.. We’ll be washed with palm wine and packed with sawdust and resin-soaked balls of linen, anointed with oils, and wrapped with strips of our own bedding. The wrapping alone takes upwards of 20 days. You’ll be given a shroud and a death mask and put in a sarcophagus. This attention to detail means some future British archeologist will have the opportunity to stare into our preserved, not-quite-as-beautiful faces thousands of years from now. Though not all mummified bodies will be so lucky. Some will be uncovered and moved by tomb robbers. Others will be ground up to make a popular Pre-Raphealite paint color called “Mummy Brown.” ‘Hey, Giuseppe? Could you pass me the ground human remains? It does AMAZZZZING things for my portraits of Jesus.’ When an artist named Edward Burne-Jones learns that one of his favorite mixers is actually made up of long-dead body, he grabs his final tube of the stuff, digs a little hole in his yard, and gives it a proper burial. But the paint won’t fade out of the artistic scene until the 1960s, when paint makers will run out of the stuff, and their access to mummies. Ah, for the good old days!

The soul goes on a perilous journey; you’re gonna have to work for that sweet place beside the gods. Once you reach the Hall of Judgement, you’ll stand before the 42 divine judges and explain away any mistakes you made. Then you’ll have your heart weighed against the feather of the goddess Ma’at, as that’ll tell us if you’ve been virtuous. Worried about the weight of your heart? The Book of the Dead left in your tomb is like a handy afterlife cheat sheet, filled with 400 spells you can recite in moments like these. But if you’ve been TOO naughty, Ammit the “Devourer” – a woman, of course – might eat it, condemning you to eternal darkness. She is terrifying: part croc, part lion, part hippo. Get it, Ammit: I’m into it.

If you prove worthy, you'll go before Osiris and be welcomed into the afterlife. This’ll involve a lake, some boating, and then finally settling in to your new plot of land in the Field of Reeds. Whew: that was more epic than Lord of the Rings, but with fewer hobbits!

The ancient Egyptians were obsessed with life, not death: with the ability to feast, love, and be merry. They glimmered with jewels, held larger-than-life festivals, loved a drink and a hearty laugh. So as we walk across those eternal midnight fields, let’s linger over that poem written back on our tomb wall:

So seize the day! Hold holiday!

Be unwearied, unceasing, alive

you and your own true love;

Let not the heart be troubled during your

sojourn on Earth,

but seize the day as it passes!

Next week, we’re going to explore the lives and times of some of the most powerful women in the ancient world: Egypt’s queens and lady pharaohs. We’ll walk with them through the gilded halls of their palaces and into the shaded dens of royal harems, exploring what life was like at the top: and how, amidst a patriarchal system, they found a way to rule their world.

Until next time.

Music

“Hathor,” “Nefertiti,” and “Lost Tombs.” From the album Ancient Egypt, Derek and Brandon Fiechter.

“Journey of the Nile, “Festival Dance,” and “Jewel of the Desert.” From the album Children of the Nile, Keith Zizza.

All other music licensed from Audioblocks.com.

logo, theme music and artwork

Paul Gablonksi

Voiceovers

Avery Downing

Phil Chevalier

John Armstrong

Rae Reynolds from The Womansplaining Podcast