Who Runs the World: Ancient Egypt's Female Pharaohs

In ancient Egyptian, the word pharaoh doesn’t mean king; it means “great house”. They had no word for queen at all.

All royal women were defined by their relationship to that house: with titles like Great Royal Wife, Great Royal Daughter, Great Royal Mother. They were there to support, not to rule. And yet, in an ancient world where men ruled the day, Egypt saw a slew of influential females stalking the gilded royal halls. Some were royal wives and mothers, whispering in their pharaoh brother-husband’s ear, and some stepped in to rule for him when he was too young to do it himself. But then, others were pharaohs in their own right, beating the odds to rule alone.

Who were these women? How and why did they get to be pharaohs, when so many of the ancient world’s major empires never suffered a woman to rule? What was life for a woman on top? And what did they have to do to stay there?

Grab your eyeliner, a vulture headdress, and your crook and flail. Let’s go traveling. Before we do, though, make sure you listen to the first two episodes of the season on everyday life for the ladies of ancient Egypt. It’ll help you appreciate the world we’re about to travel through.

lead me to greatness.

Image from queen Nefertari’s tomb, courtesy of kairoinfo4u on Flickr

my resources

BOOKS & mags

Ancient Egypt: Everyday Life in the Land of the Nile. Bob Brier & Hoyt Hobbs. Sterling Publishing, 2009. This was mega helpful as a reference when it came to all the different aspects of Egyptian life: such a great overview of the nitty gritty!

When Women Ruled the World: Six Queens of Egypt. Kara Cooney, National Geographic, 2018. This book served as the backbone for my episodes on these Egyptian ladies and was really helpful in helping put their lives and world into modern-day context.

The Woman Who Would Be King: Hatshepsut's Rise to Power in Ancient Egypt. Kara Cooney, Penguin RandomHouse, 2015.

Cleopatra: A Life. Stacy Schiff, Virgin Books, 2010.

Daughters of Isis: Women of Ancient Egypt. Joyce Tyldesley, Penguin, 1995.

Nefertiti’s Face: The Creation of an Icon. Joyce Tyldesley, Harvard University Press, 2018.

Dancing for Hathor: Women in Ancient Egypt. Carolyn Gaves-Brown, Continuum, 2010.

Women in Ancient Egypt. Barbara Watterson, Amberley Publishing, 2013.

Amazing Women in History. History Revealed Collector’s Editions, 2018. This is such a great little gift title, full of women from across time periods and cultures, taking readers on a very visual journey of what made them great.

PODCASTS

The History of Egypt Podcast by Dominic Perry. If you’re into Ancient Egypt, this podcast is amazing: very thorough, scholarly, and with tons of details that help bring ancient Egypt to life. His individual episodes on Hatshepsut (Episodes 61-66) and Nefertiti were particularly helpful, along with his interview with Joyce Tyldesley.

“Episode 45: Hatshepsut.” The History Chicks.

ONLINE

“Egypt’s Lost Queens.” Timeline documentary, on YouTube. I enjoyed this doco hugely: it takes you to many of the places I talk about in these episodes and looks at them all through a ladycentric lens. Well worth sitting down with!

“Hatshepsut.” Ancient Encyclopedia.

“How three rebel queens of Egypt overthrew an empire and gave birth to a new kingdom.” National Geographic History Magazine, 2019.

“The King Herself.” By Chip Brown, National Geographic Magazine. Such great pictures of Hatshepsut’s architecture and her MUMMY! Nat Geo has a LOT of great ancient Egypt content: just search their website for the queen/lady pharaoh you’re interested in.

“King Tut, Queen Nefertiti, and One Tangled Family Tree.” National Geographic.com.

The Birth of Hatshepsut, translated by James Henry Breasted.

images I couldn’t get the rights to use, but that are well worth checking out

To see some really amazing images of Nefertari’s tomb, check out this account on Flickr.

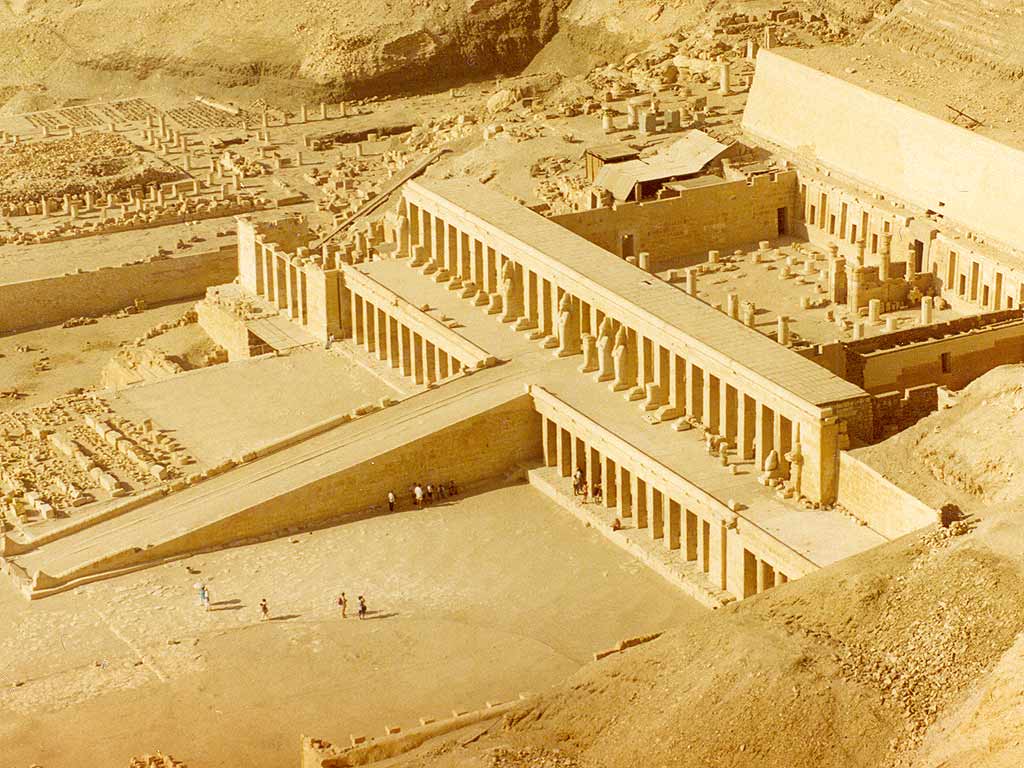

“This Temple Honors the Egyptian Queen Who Ruled as King.” Travel, By Gulnaz Khan. Some great pics of Djeser Djeseru.

“King Tut: The Teen Whose Death Rocked Egypt.” National Geographic. This one has a good visual collection of King Tut’s fabulous tomb offerings.

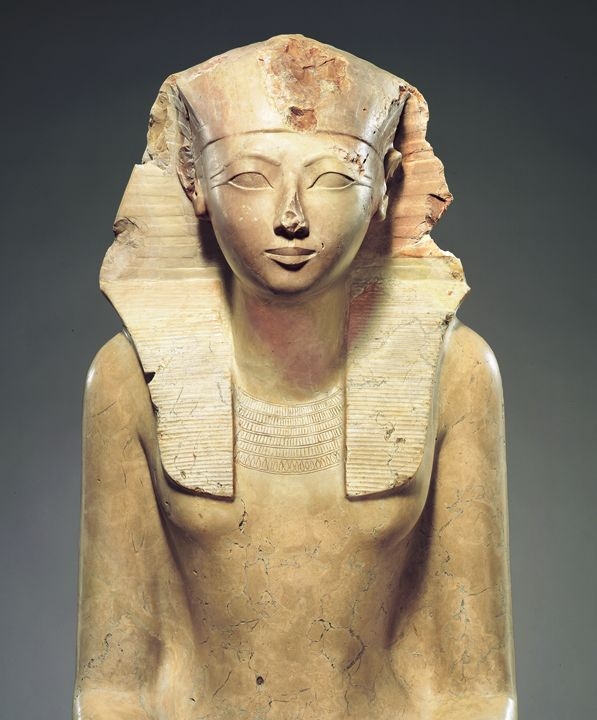

who says a lady can’t be a sphinx and a pharaoh?

Statue of Hatshepsut, courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

transcript

keep in mind that I ad lib a bit as I record, and I add and delete bits in editing, so this won’t be exactly what you hear on the airwaves. Also, there are likely to be a few spelling or formatting errors: forgive me. And if it isn’t obvious already, a lot of these ‘direct quotes’ are things i made up. i’ve left all of the fictitious quotes in bold, just to be clear about it.

WHAT MAKES THEM BOW DOWN

Let’s hover over Egypt for a minute and contemplate what social and political conditions are creating room for these enterprising women to rule.

As we talked about in our last two episodes, Egypt is an incredibly rich nation, isolated for much of its history and cushioned by the bountiful riches of the Nile. All that wealth has made them something of a risk-averse people. If it ain’t broke, don’t fix it, know what I’m saying? And so they want nothing more than stability: for things to stay the same at all costs. And that means pleasing the gods above all else. And the pharaoh IS a god: or, at least he’s the son of one. The first father/son pharaoh duo was Osiris – remember him of the golden phallus? – and his son Horus; the pharaohs ever after are descended from those gods by blood. That’s what gives them kingly authority.

But who’s the one who got them onto the throne? Isis: no, not the group you’re thinking of (the goddess Isis must be pretty pissed about what those guys have gotten up to). She’s the goddess who located all of her husband’s pieces after the god Seth chopped him up, and then used sexy magic to literally excite him back to life. She was the key to his resurrection and his kingship: without her, they would never have had a royal son.

Which all goes to prove a crucial point for ancient Egyptians: you can’t have a Horus without an Isis. Royal women are divine too, connected to the gods in their own right, and they’re crucial to keeping our world in perfect balance. It’s from them that the royal seed flows, keeping the family line strong. If Egyptians believe in anything, it’s that that line should NEVER be broken. Sometimes, when there are no men to do it, that requires a woman to rule.

If you like this ladycentric map of ancient Egypt, go ahead and buy yourself a copy over in my Etsy Exploress merchandise shop.

And guess what? Egyptians don’t see them as a threat, in general, because these women are related to the king. As his mother or wife, she’s there to HELP the pharaoh, not depose him. Why would she try to do away with her source of her power? Having a lady beside him makes the pharaoh safer and more powerful.

There’s another reason the ladies make good rulers, and it’s rooted in the idea that women aren’t violent. When a king dies and there’s no obvious successor, or one who isn’t old enough yet to take the reins, who would you rather have step into the power vacuum: a military warlord who’s bound to start stabbing people and start expensive wars? Or a woman, who is less likely to rape and pillage and more likely to keep things on an even keel? Women are bridge builders, not bridge burners. That makes them perfect for filling in a power gap.

A little sexist, ya think? Sure. But does this attitude give women room to bust through that pyramid-shaped glass ceiling? You know it.

We see women stepping up from Egypt’s very first Dynasty, when Merneith steps in to rule for a son who’s too young to do the job. Like pretty much all of our ancient lady pharaohs, she’s a shadowy figure. The Egyptians didn’t write down a whole lot of the juicy stuff: coups, spicy rumors. They didn’t leave us tell-all memoirs. So we know frustratingly little about her, other than she ruled around 3000 BCE. If I were you, I’d go to my website and break out both the pretty timeline of ancient Egypt AND the handy map I made you, as it’ll help set these stories straight.

That was when the Dynasty system was still pretty new, and being a royal was a very bloody business. Her name is extra violent: it comes from Neith, a vicious huntress, one of Egypt’s oldest goddesses – and one of the fiercest.

To understand Merneith, we’re going to have to slide into her slippers and make some suppositions about what her life might have been like. She grows up in luxury in a mud brick palace: picture cedar wood, fine imported wine, fat cuts of beef. As she gets older, she’s no doubt slapping that dark green malachite eyeliner we talked about. Or, more likely, a makeup artist is applying it for her. But there’s a dark side to being an early Dynasty royal. Later on in our timeline, we’ll see royal siblings just blending into the woodwork when a new pharaoh is chosen from amongst their ranks. Most of their names aren’t recorded in official chronicles, because it’s unlikely they’ll ever be king. Why give them ideas? Instead, they’ll go off to do other things, and maybe that’s why it doesn’t seem as if they ever come roaring back to try and stage a coup.

But in the beginning, when they’re still sorting out the Egyptian Empire, the transition from a recently deceased pharaoh to a new one is a stressful time. So all potential threats to the kingship are sacrificed to the dead king and buried with him. Not slaves or prisoners, but brothers, lovers, wives, sisters. And they’re not to go kicking and screaming, either: step right on up to the knife smiling, shall we? Yikes. These sacrifices are meant to tell all those left behind who’s in charge, and that they’d better not question it. And it seems as if it works a royal treat.

We don’t know how these lucky souls are chosen: straws? A cutthroat version of musical chairs? But hundreds of people were buried with a guy named Djer, the first king of Dynasty 1, promising them a place in the afterlife. Merneith, his daughter, could easily have been one of them.

Who’s the biggest threat to the next king? That all depends on who’s made pharaoh. Though many scholars think the transfer of power in ancient Egypt is generally straightforward – passed to the eldest royal son – we don’t know for sure, and sometimes it definitely isn’t. We think that a priest sometimes chooses the new pharaoh from the king’s many sons in some kind of mysterious ritual. Merneith has to be wondering: was she destined to die with her father, or to become more powerful than ever?

She’s there at Saqqara to watch the chosen be killed. Her family members, friends: some 600 people, all taken from her. Who are they? We don’t know. But archeologists tell us that some 85% of the people sacrificed at Djer’s site were women. This is Merneith’s bloody world.

After that lovely little desert-side picnic, she’s marched off to be a member of her new king’s harem. The new king, Djet, is her brother. But no one’s batting even one eyelash over that.

Step right up and marry your brother!

This image from queen Nefertari’s tomb comes courtesy of kairoinfo4u on Flickr.

TALKIN ‘BOUT INCEST

Make some popcorn and let’s talk about royal incest, shall we? There’s a conception that it’s common practice amongst Egyptians at large, but that’s not true. Confusingly, Egyptian literature often uses the words ‘brother’ and ‘sister’ in love poetry as terms of endearment, kind of like saying ‘my dearest one’. In truth, brother-sister-father-aunt-style loving isn’t common, except within the royal family. And they sure do marry their brothers a LOT.

But whyyyyyyyyy?! Because here’s the thing: they must KNOW this practice produces weaker babies. They can see the results with their own eyes: there are pharaohs with club feet, and more than one that proves sterile. So why do it? Well, for one, the gods do it: there are all sorts of brother-sister pairings in our pantheon, and Egyptians are pious to a fault. But really, that’s just a convenient justification. They do it because it keeps the royal seed and its power contained. You don’t have to deal with meddling in-laws when you marry into your own family. You don’t have to arrange any dowry for your daughters. And you don’t have to worry about some distant relation or in laws trying to move in on your throne...theoretically. Remember the English War of the Roses, which involved such a tangled web of dubiously connected family members that it ended with some son of a king’s half-brother riding through all those rivers of blood to be like, “it’s my time, bitches!” Egypt’s closed-loop system means we’re not worrying about any of that hot mess.

And ok, yes, it’s fairly icky. I’m sure Merneith also finds it icky. “Oh, I do. I really do.” But on the bright side, all this incest creates a special space for royal women: a closed system gives them multiple titles, a new kind of importance, and a whole lot of power.

So there Merneith is, getting it on with her brother-husband, trying to have royal babies that might one day be king. Because as far as titles go, Mother of the King is one of the most potent you can win.

But she isn’t the only one. Most pharaohs have a royal harem, and lady favorites outside of it. Some are given the title “ornament of the king,” chosen to entertain him with singing and often scantily clad dancing. These women often become important members of court and take an active part in royal functions. So it’s not like Merneith doesn’t have competition.

But then her brother-husband dies without ceremony, as they’re wont to do, leaving no sons old enough to rule. “RIP, brother-husband.” Luckily Merneith’s son is the chosen one, which means she gets to step in and keep the seat warm as regent until he’s old enough to claim it. As much as I’d love to tell you that Egyptians are over the moon about female rulers, they aren’t overly keen unless it’s to help out a son, as here. In such situations, she isn’t a threat: she’s there to help protect her son’s power, after all, and thus keep her lineage unbroken. Merneith milks that little loophole for some 6 to 8 years.

Her first job as regent is to bury her husband, and that means choosing people to sacrifice and bury with him. So she gets out that pointer finger and starts going, “eeny, meeny, miny, mo!” The burial site suggests she chooses fewer people, and fewer women, than her forebears, but more people of import. She’s a quality-over-quantity kind of gal. She probably used the opportunity to eliminate people she saw as threats: young women and children were buried together, maybe because they were too close in the line of succession. That’s cold, Merneith. “What can I say? A lady’s gotta rule.”

She and her son Den make sure that papa Djet has everything he’ll need in the afterlife: tools, furniture, goods, and a magic wand: naturally. Even some of his dogs are sacrificed. She also uses the opportunity to leave her name all over the tomb in a brilliant ancient PR move: one stone vessel calls her “She Who Is United With the Two Lords,” highlighting her role as connection between the past king and the present one. If it’s carved into a fine building, then it must be true. This is something Egyptian lady pharaohs will use over and over again.

The question is this: when we know so little about her, how do we even know she ruled? Because her name makes it onto some of the king lists discovered in her son’s tomb: official records of kings past and present. Yes, her name does appear with a tab that says “King’s Mother,” but she’s there: and why would she be, if she didn’t matter?

Her tomb will be discovered in 1900 in a royal necropolis at Abydos, and the British guy who finds her will assume she’s a king. It is, after all, the place where all the First and Second Dynasty kings are buried. She won’t have the customary hawk hieroglyph meant to symbolize Horus, which is puzzling. But once they realize, they’ll know that she must have been powerful indeed for her son to have buried her in his necropolis.

hetepheres’smobile throne chair. yas queen!

Courtesy of the Museum of Fine Art Boston

Merneith isn’t the only woman to be given pride of place in the afterlife by a pharaoh. Mothers, wives, and sisters are seen as crucial to a ruler in life, but also in his afterlife. When a pharaoh is buried, his most important women are often buried close by. Khufu, that guy who built one of the great pyramids of Giza, made sure to add a sumptuous pyramid next door for his mom, Hetepheres. She was even interred with a mobile throne chair, the back of which he painted with all her titles, one of which was “she whose every command is carried out.” Every wish her command as she’s carried around in a traveling lounge chair? Hetepheres was really living her best life.

We know so little about Merneith’s achievements and her struggles, but we know she mattered. Safe travels in the afterlife, you trailblazing queen.

Acting as regent for a baby pharaoh isn’t the only way into power. There are the women who come at the end of their family’s line – their very last gasp before a new Dynasty rises out of the sand. These women are often allowed to rule, perhaps revered as the last divine vestiges of their families, or perhaps because they don’t seem to pose any threat: again, better to deal with a lady pharaoh than the uncertainty of no ruler at all. And they allow the Egyptian elite time to sort out who will rise after her. Not glamorous, maybe, but that doesn’t mean she can’t make some power moves while she’s there.

Because unlike Merneith, this next woman gets to rule without a baby monarch beside her: circa 1777 near the end of the Middle Kingdom period, she rules alone. Her name is Neferusobek, or Sobekneferu. Egyptian elites change their fancy names more than Prince.

Though, when you think about it, it’s kind of bizarre that any Dynasty could run out of male heirs: for most of Egypt’s history, the pharaoh has himself a harem whose sole job is to pop out tiny kinglets. While most Egyptians are monogamous, the pharaoh isn’t: he can’t afford to be. In some ways, he has the most publicly owned sex life in the ancient world. He’s the royal bull of Egypt: when he engages in a horizontal tennis match, he’s actually helping to father the ongoing cosmos. His sexy time keeps the world turning round.

Dozens, and later even hundreds of women live together in these royal harems, making sure he has an heir and about a thousand spares on the go. Lethal Lothario Ramses II will have some 50 sons during his lifetime...and that’s not even counting the girls. Neferusobek is born into the Middle Kingdom and Dynasty XII, more than 1,000 years after Merneith was cutting people. She is one among many King’s Daughters, and she spends much of her life in the harem’s halls.

LIVING THAT HAREM LIFE

Let's step into the harem for a minute, shall we? Like ancient incest, this is another place we modern gals have trouble understanding. While you might be picturing gold chaises, silk curtains, red lights, and many orgies, you’re mistaken. Mostly. In ancient Egypt, the word “harem” is synonymous with “women’s quarters”: in any household, royal or not, this is the place where women live and play together. In non-royal houses, it’s often a bachelorette pad where unmarried gals drink Cosmos and have pillow fights in their underwear. Because that is definitely what women do in their free time! Though it must be said that, in the royal harem, there is certainly sex being had. But these women aren’t considered the king’s spicy side pieces: they’re his wives, and with that position comes a whole lot of splendor and the chance to one day be Mother of the King.

The harem has its own power structure, and Neferusobek would have been mixing and melding with girls from all over, bought in diplomatic marriages meant to smooth over hurts and build bonds with other empires. Future 18th Dynasty pharaoh Amenhotep III has at least six foreign brides in his harem, as well as a gaggle of Egyptian ones. He is also a bit of a dog, apparently, because when his Syrian bride arrives with 317 female attendants, he writes the following note to his vassals: “I am sending you my official to fetch beautiful women, to which I the king will say good. So send very beautiful women, but none with shrill voices.” Bite me, Amenhotep. But even this lady-hungry pharaoh still has a main squeeze, who even conducts some of her own diplomatic correspondence. Her name is Tiye, a commoner who rises up to become his #1 Great Royal Wife. The Great Royal Wife runs things in the harem: she is the highest woman on the totem pole. She and any Sisters of the King have a definite advantage in this environment. If you’re a country gal brought in to liven things up in the harem, you’d better mix your own drinks and birth nothing but girls.

The royal women's quarters are confined in its own compound, usually attached to the royal palace for ease of access, complete with a courtyard featuring pools, fish, fig trees, and probably a few monkeys, a popular pet amongst harem girls. All children are housed in a nursery in a separate wing, tended to by wet nurses and nannies. A staff manages the land and property around it, as ideally it’s supposed to make some money. Harem women might even run their own business, supervising female weavers. It costs a lot to feed a harem: one pharaoh apparently requires 2,000 loaves of bread and 300 jugs of beer for his dining table every evening, and he wasn’t even a very rich one.

The harem is run by the Overseer of the Secluded, who manages the scribes, attendants, and the door keeper, who works out the pharaoh’s sex schedule. I mean, when you have dozens of ladies whose job it is to have your tiny kinglets, it’s easy for your nights to get double booked. To try and speed along conception, the harem girls are eating poppy and pomegranate seeds, burning incense soaked in fat, probably praying, and keeping their fingers crossed.

And there’s a reason they’re called the Secluded: this is a fine, but very sheltered life. Many harem girls wile away the time between sex sessions at the loom, weaving linen, or learning how to play instruments like the sistrum, a sacred rattle. We can only imagine what they get up to on a Saturday. Ancient harem dance partyyyyyyy!

shake it, fellow wives!

Female musicians and dancers, Wikicommons

Without a whole lot to do, the competition here is like The Bachelor on steroids, but with the possibility of poison. I’m sure some of these women form lasting friendships. But it is NOT all hair braiding and sweet secrets up in here. And listen: as a harem girl, you are NOT allowed to sleep with anyone besides the pharaoh. If he’s too young, or too old and infirm, then you’ll be having very little sexy time with anybody. One suspects there MUST have been some same-sex romance happening. Or some side action with the guards, who curiously don’t seem to be eunuchs, as in other places. Maybe because they know that if they’re caught, their balls are gone.

But harem women aren’t always keen to sit back and let the gods decide their fate. They may not always have much power, but they have access: and that means they’re in a better position to either influence the pharaoh - or off him - than anyone else. Members of Ramses III’s harem plotted to kill him as part of a palace coup—and they did it. It seems to have been led by Tiy, though not the same one from before, who wanted her son Pentawere on the throne. In the ensuing trial, several women are accused of having made wax figures and used black magic as part of the assassination. Wait: have I heard this one before? Oh, right, those many European witch trials. History is gross sometimes…In the end, 38 people were put to death, condemned either to kill themselves or be impaled by a spike. Choices, choices.

Given the limitations of ancient medicine, the harem sees a lot of tragedy at the birthing block. Sadly, some half of royal children will die before their first year is up. Baby boys are cause for celebration, but when girls appear, the party is a little more subdued. The pregnant woman isn’t blamed if she bears a girl. In fact, she isn’t blamed if she can’t conceive, either. That’s refreshing.

*RING*RING* hello, Henry XIII? Yeah, it’s ancient Egypt. So about you saying you want that divorce from your wife Catherine because she hasn’t borne you sons? It isn’t Catherine, man, it’s you. No, listen. It’s your man seed. It’s weak. Get stronger man seeds!!

And so Neferusobek appears. Her name means “The Beauty of Sobek”, named after a fierce crocodile god who is the patron of the army, a protector of pharaohs, and apparently virile as all get out.

The Egyptians left us so little juicy harem gossip, so we can only really imagine what kind of drama she’s dealing with on the daily. She probably grows up with her ears wide open, learning from some of Egypt’s great schemers. They teach her how to be patient, how to be fake, how to be flexible. All skills that will serve her very well.

Sad to say, sex would be on her mind from an early age. With a king who lives as long as her dad Amenemhat III, Neferusobek will grow up expecting that she might just have to become his Daughter-Wife. Her sister does. Woof…now that’ll give you daddy issues.

When Neferusobek’s dad dies, he is 50 or 60: super old by ancient Egyptian standards. And somehow, he has no son – maybe he outlived a lot of them, or maybe he just wasn’t good at having them...we don’t know for sure what the deal was with that. We do know that a guy named Amenemhat IV proceeds to come out of the woodwork; scholars debate whether he is actually the son of the king at all. At any rate, he marries Neferusobek, who he’s in all likelihood related to somehow, and they rule together for nine years. But then he dies, once again leaving no male heirs. And so Neferusobek steps in, not to rule for a baby king, but as the last royal family member standing. She is it, so everybody leans into it. But because she’s a woman, she has to work twice as hard to prove her right to be there.

So she gets busy feminizing the language of kingship. Pharaohs take on official king names, which always have a very extra five-name titulary, each piece of which defines the ruler’s legacy.

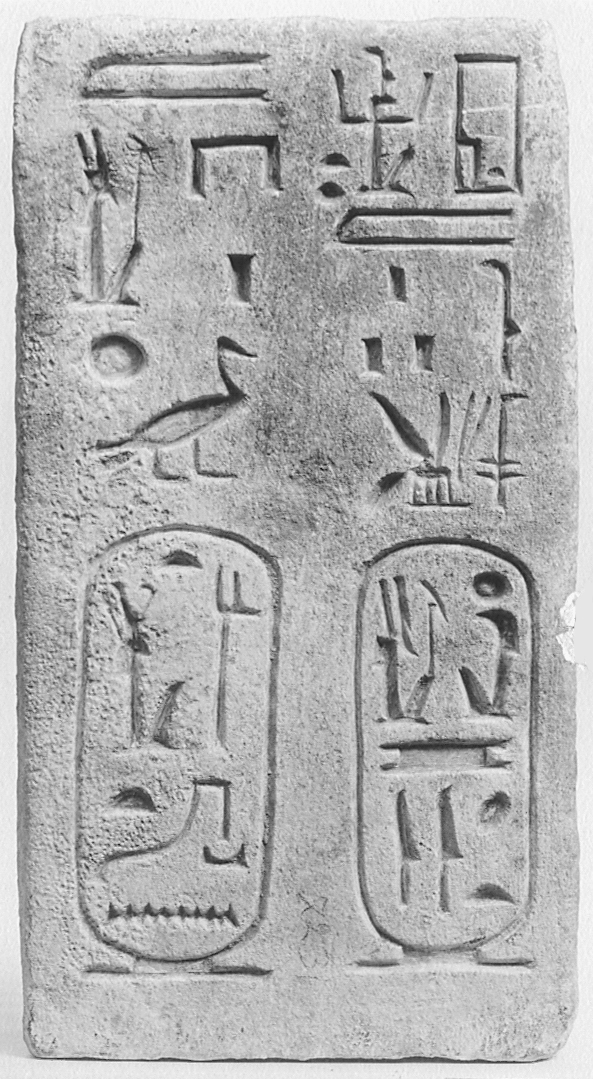

The oldest part is the Horus name, asserting that the king is godly; the Nebti or Two Ladies name shows they have claim to both halves of Egypt; there’s a Golden Horus name, a prenomen, or throne name, and a nomen, or birth name. As the first official lady king of Egypt, she basically breaks the mold when it comes to her title, femininizing the language in ways it has never been before. Her Horus name, “Beloved of Re,” is written as Heret, not Her, which takes the falcon bird that is the symbol of kingship and makes it into a lady bird. Her Two Ladies name is “The Daughter of the Powerful One is (Now) Mistress of the Two Lands.” So, she’s the daughter of the king and has the right to rule, AND she’s a lady boss.

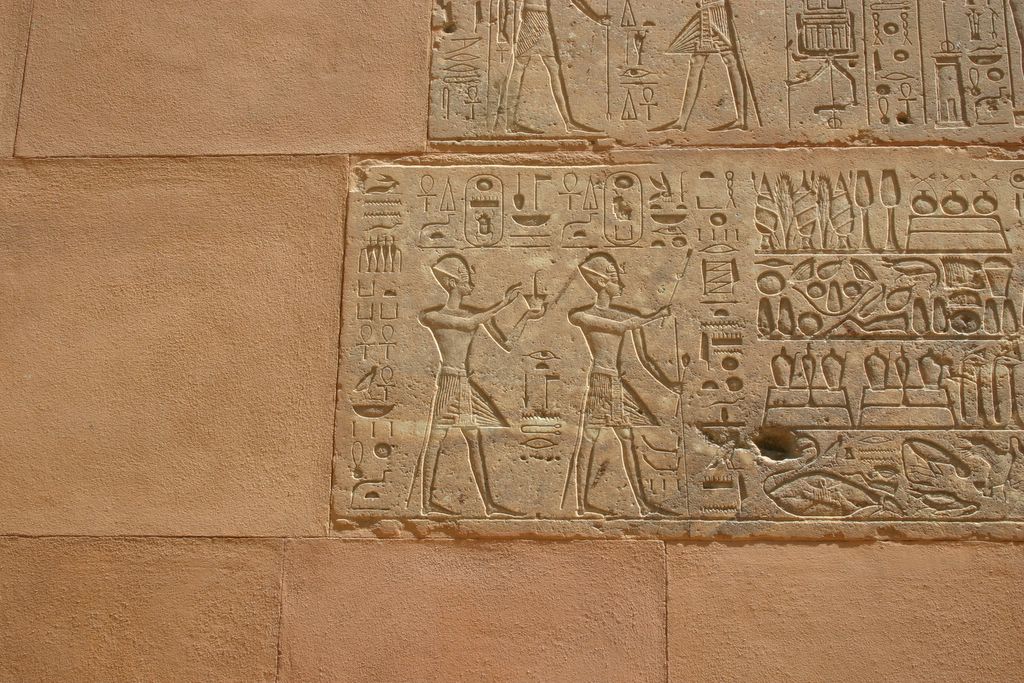

She also does what all great pharaohs do and has her image installed all over Egypt. These stelae and giant images are walking billboards, shouting to all who she is and that she matters. In these, she uses powerful symbols to cement her authority: much like lady politicians do today, she knows that she needs to dress for the job she wants. She makes little attempt to mask the fact that she’s a woman, but her statues show her wearing pants and the traditional Nemes head dress: the era’s power suit. She might as well say,“hey everybody, yes, you heard right. I’m a lady. But dammit, I’m rocking these royal pants! So deal with it.” She also prioritizes finishing her father’s tomb at Hawara, strategically putting her name all over it to visually align herself with her father. She gets to look pious, filial, AND legit. Smart, Neferusobek!

But soon she’s facing a year when the Nile fails to perform its usual magic, leading to famine and general upset. To top that off, given that she’s the end of her Dynasty, the nobles around her are probably forever talking about who will be next in line. Tough to finish your performance when you can see the audience members eyeballing their watches. All we can hope is that she has her own harem to take the edge off, but she probably doesn’t. Hopefully a well-sculpted side piece or two, at the least.

So does she marry someone and have some royal children? We don’t know, but it doesn’t look like it. Which is too bad, because it seems like the Egyptians considered the woman to be the keeper of the royal divine seed. Maybe the nobles around her make it clear that they won’t be letting that happen.

Again, we know only enough about Neferusobek to be tantalized by her: and then she dies after almost four years as lady king. From what evidence there is, it seems likely that she wasn’t killed by foul play, and that she was buried respectfully – she even has a cult of people who look after her temple and her afterlife. And her name can be found in many king lists, marking her forever as a woman who ruled.

Fast forward some 300 years to the New Kingdom and the 18th Dynasty, and we arrive at the feet of the most impressive lady pharaoh of them all: Hatshepsut. She seizes power when Egypt is soaring high and finds a way not only to hang on, but kick ass.

GRABBING THAT FLAIL AND RUNNING WITH IT

But let’s back up in time for a sec. In the 2nd Intermediate Period, the period of time between Neferusobek and Hatshepsut, Egypt becomes a divided country - one at war with the Hyksos, a Greek word for “foreign invaders,” from the area we’d now call Palestine. They swoop in and rule from Dynasties 15 and 16, bring chariots and horses and a whole lot of sass. But native Dynasty 17 isn’t about to lie down and take it, and it rides in on the back of some powerful women.

When the 17th Dynasty men march off to war, they leave a Royal Wife named Tetisheri in charge of Upper Egypt. This woman not born to a noble family holds down the fort, proving such an asset that her husband makes her the first queen to wear the vulture headdress of Nekhbet, which future power-hungry queens will want to rock. Some call her the mother of the New Kingdom. She also strongly influences her son Seqenenre Tao and grandson Ahmose I. Although when Ahmose is young, he’s got another lady in his corner: his mom Ahotep, who probably steps in and rules for him when he’s too young to do it himself. This fierce regent is key to continuing to fend off the Hyksos: so much so that she was buried with military goods. “She governs vast numbers of people and cares for Egypt wisely,” reads a stela about her at Karnak. “She has attended to its army; she has looked after it; she has forced its enemies to leave and united dissenters; she has pacified Upper and Lower Egypt and made the rebels submit.” Yeah she did!

Ahmose I kicks off the 18th Dynasty by marrying his sister Ahmes-Nefertari. When he dies and their son is still young, Ahmes-Nefertari rules in his stead, helping to build a reunified Egypt in the wake of years of war. She’s also one of the first royal women to hold the religious office of God’s Wife of Amun. Amun is one of the most powerful gods in Egypt, and his ritual wife is a high position indeed. In sum, the New Kingdom is rife from the get-go with smart ladies more than capable of running the show, and they’re not afraid to go ahead and do it.

But Egypt has a problem: Ahmose I produces no heirs. And thus somehow, a guy named Thutmose I is named pharaoh, probably with help from Ahmes-Nefertari. Is his mother royal? We don’t think so. Is his father royal? No idea, but he never calls himself King’s Son, so…probably not. Vague pedigree aside, he turns out to be an outstanding pharaoh. This warrior pushes Egypt’s borders out further than they’ve ever gone, crushing Nubia under his boot heels. He shocks the aristocracy by doing something new: instead of building grand pyramids, he decides to trick would-be looters and build his mausoleum underground. He’s the first person to have a tomb in the famous Valley of the Kings, tucked away from prying eyes. And he has him a lot of royal children via his harem in Thebes. His eldest is a daughter named Hatshepsut. Her mother is Ahmes, the king’s royal wife.

After only a few months, Hatshepsut is taken away from her mother and given over to a royal wet nurse, who holds one of the most coveted and powerful positions a non-royal woman can have. This woman, Satre, remains close to Hatshepsut and important to her throughout her life, and is probably more of a mother to her than Ahmes. She grows up running around naked with other royal children in a rich and sheltered world. She probably has to shave her head to keep the lice at bay, which is probably extremely low maintenance. Though as she gets older, she isn’t running around with the boys as they learn to hunt and have chariot races. She’s stuck in the harem, chatting textiles and sex positions. She’s a smart girl who wants to learn about the world, which probably makes her stick out from the crowd. We don’t know much about her education, except that she is likely to have one: the best an Egyptian can buy, and one that most women of her time aren’t getting.

We don’t know how old she is when she gets her first job, but it’s a doozy. As #1 Royal Daughter, Hatshepsut wins herself the coveted title of God’s Wife of Amun. Amun is incredibly powerful, and his system of temples and the people who serve him is extensive: almost like the ancient Egyptian version of the Vatican. This position provides her with her own coin money, independence, and power. In a land that feels strongly about the gods, she has one of the highest religious posts of them all.

Let’s talk about religious ritual for a minute. Remember that most everyday people aren’t just walking into a holy place and patting a god’s statue for luck, or whatever. Each god has their own temples in different cities, run by priests that are mostly men. But women are also involved in servicing the gods they worship, which really is a full-time job. These temples are considered the gods’ houses, and every day these priests and priestesses need to call the god into their statue, which they treat like it’s an actual person with feelings and many, many needs. Hatshepsut wakes the god up in the morning with incense and rituals, then lays out a full breakfast for him to enjoy. Her duties ALSO include exciting Amun: yes, sexually exciting him. Because Amun’s daily sexual completion helps keep the royal family going and the world continually turning. As god’s wife, she’s likely to spend some time shaking a sistrum for his giant statue, singing along to her favorite Beyoncé song. She might then take the statue’s erect and…shake it? What ya doing, Hatshepsut? “Oh, you know. Amun and I are just having a little alone time.”

This new life is full of luxuries, but also a lot of responsibilities, requiring her attention before the sun rises and after it sets. But it’s a rare privilege to see and participate in rituals with this powerful god, especially for a woman. These are sacred mysteries known only to a few. And it’s a great place to network: a way to make connections with some of Thebes’ most powerful priests.

And then, around age 12, something terrible happens: her two oldest brothers, Wadjmose and Amenose, die. Given that her dad has already written Amenose’s name on one of his temples, which most kings don’t do until a kid is chosen as the next pharaoh, he’s got to be pretty cut up about it. Everything is in chaos: who’s going to be the next to rule? Hatshepsut is definitely the most eligible and well connected of the harem children…but she’s a girl, so a young, sickly son is plucked out of the harem and dubbed Thutmose II. If his mummy is anything to go by, this guy was not his warrior father’s son in terms of physical prowess. No one is pleased about this new king, and I can’t imagine Hatshepsut’s thrilled about him either.

He’s still very young, and it’s clear he needs a female regent to step in and help him. So in steps Ahmes, Hatshepsut’s mother, even though she is most definitely NOT this kid’s mom. This is unusual: the mother of the king is supposed to, you know, be the regent. But maybe Ahmes is just too powerful to be denied.

She pushes to have Hatshepsut marry this half-brother and become the King’s Great Wife. Given that Hatshepsut is descended from royalty on both sides, she actually makes HIM look more kingly. So these two female powerhouses high-five in the throne room and get to ruling the country as best as they can.

What is her relationship with her young husband like? We don’t know. But we know she and mom make themselves very visible and exercise a decent amount of influence over Thutmose II. I think they steamroll him from an early age. Early in his reign there’s a rebellion in Kush, down in Nubia, and Ahmes organizes a force to go against them. All in Thutmose’s name, of course. They also include their own names alongside Thutmose II’s at Karnak: a bold move. Hatshepsut’s show her doing things that usually only a king should be doing: standing before Amun and holding out an offering without the king standing between them. Scandal. Though maybe these don’t ruffle many feathers: she is Amun’s wife, after all.

In sum, she and mom are totally overpowering Thutmose. And he’s like: “Fine, whatever. I’d rather ride around on my chariot and shoot things anyway.”

Eventually, Hatshepsut bears him a child: a daughter called Nefrure, whom she seems to keep closer than most queens keep their kids. When she gets old enough, Hatty invites a man to be her daughter’s tutor: his name is Senenmut. Though this guy previously had no palace connections, he finds his way into the ladies’ service and suddenly he is very influential. He’s handling the money and advising Hatshepsut in her doings. Some say that he is doing HER, though we have no evidence that they are ever a thing. Don’t we just love accusing queens of sleeping with people?

But she still hasn’t produced a male heir. Lucky for her, there are other harem girls to do this for her. Or unlucky, because these tiny kings and their mothers are a threat to her position if she can’t have a male heir. And then, after just three years at the top, the king dies. And so at the tender age of 16, Hatshepsut has to fend off any wannabe pharaohs – or, more accurately, the team of people rallying around them – and try to make sure the next pharaoh is one she can control. Because if she can’t, her star is not going to keep rising.

How the next pharaoh is chosen isn’t clear: we think the statue of the god Amun selects him in some kind of ritual. As God’s Wife, Hatshepsut is probably there: she may even have pulled some strings with old Amun behind the scenes about this whole selection process. Regardless, a new tiny kinglet is chosen, who will soon be known as…of course…Thutmose III. I mean, we can’t exactly name him John.

He’s the son of a lesser wife named Isis, but bizarrely, Isis doesn’t step in to become the King’s Mother. Nope: just like her mom before her, Hatshepsut steps right in, more than ready to serve as regent. And the country seems happy to have her, even though she’s not King’s Mother OR King’s Wife.

Why? Perhaps because war is over, trade is starting to pick up, and they really need a captain with a steady hand on the wheel. Hatshepsut has a very royal pedigree, and has already proven herself as God’s Wife of Amun. The priests love her. And amazingly, no one seems to openly question it. Ancient biographer Ineni tells us:

“His sister, the God’s Wife, Hatshepsut, was doing the affairs of the Two Lands with her plans. One worked for her; Egypt was with bowed head.”

Bow down, boys.

Next week, we’ll find out all about Hatshepsut’s kingship and meet two more Egyptian lady bosses: a beauty queen with a fanatical boyfriend and a woman who isn’t afraid to get blood on her hands.

Have fun at that sistrum-shaking dance party in the harem! Until next time.

When we last walked with Hatshepsut, she’d just elbowed a harem girl out of the way to become the official royal stepmother for the new boy king. And this time, she isn’t going to pretend that she isn’t the person making all the big decisions. She’s a little older, a little wiser, and a lot more confident than ever before.

She’s striding around the palace in a sheath dress and vulture hat, coating herself in myrrh resin to make her, in her words, “gleam like the stars before the whole land.” And people take her power seriously. She engages in religious rituals, meets with court officials, and hopefully has some steamy affairs here and there. But as the current pharaoh’s sort-of stepmother, her claim to power is only going to get more tenuous. She knows the elite families are happy to have her as long as they can push her around, and so she has to tread carefully. But to stay on top, she’s going to have to make some bold moves.

She starts an ambitious building program, erecting grand temples to honor her father and the new pharaoh, but also to serve as walking adverts for herself and her power. She gets her main man Senenmut to go and get her two giant ten-story granite obelisks – both done in quite a fetching pink – and makes sure to have her image carved in. She gets huge scenes etched into temples – in Egyptian art, the bigger you are, the more powerful – and doing things that usually only a king should be doing. In other words, she’s paving her own way into the pharaohship without actually saying she’s planning to make that move. This is a very public way to dress for the part and convince other people that you are meant to be in it.

And so it is that as early as Year 2 of Thutmose’s reign – and as late as Year 7 – she hands over the position of God’s Wife of Amun to her daughter and is crowned as pharaoh. Even though there’s an almost teenaged Thutmose in place to take it, she manages to take control. This. Is. HUGE.

Her throne name, carved into stone before she even takes over, is “The Soul of Re is Truth.” But it might as well have been “Our Lady of the Full Court Press,” because when she takes over, she’s all about building Egypt’s fortune as fast and as hard as she can.

But just in case anyone out there is still doubting her, she decides to rewrite her own history. How’s this for a big religious-political reveal: she’s not actually the daughter of former pharaoh Thutmose I, but of the god Amun. Whaaaaat?! At her mortuary temple, she crafts an ingenious story about her conception and her rise to power that leaves little room to question. First, it says, the god Amun comes to her mother Ahmes in the form of her husband Thutmose I, and “imposed his desire upon her.” And then he reveals himself in all his godly glory, which, apparently, she was totally cool with, and then, “his love passed into her limbs.” That’s a classy way to put it.

Afterward, he tells her: “Ma-at Kare Hatshepsut shall be the name of thy daughter, which I have placed in your body. ‘Go, to make Hatshepsut, from these limbs. Go to fashion her better than all the gods…I have given to her all life and satisfaction, all stability, all joy of heart from me, all offerings, and all bread, like Re, forever.” The story goes on to show her gilded childhood, surrounded by protection and the favor of the gods, saying “Her majesty grew beyond everything; to look upon her was more beautiful than anything; her [...] was like a god, her form was like a god, she did everything as a god.” I mean, bold claim, but I’m into it. She also says that her father on paper, Thutmose I, introduced her to the elites around him as his chosen successor before he died. “He who shall do her homage shall live,” he tells the court around him,“he who shall speak evil in blasphemy of her majesty shall die.” Alrighty then.

This whole thing is something later lady rulers and politicians will do to grab onto power without stirring up any overt man rage. She essentially points to herself and says, “what, me? Rule? Oh no, I couldn’t. Well…if Amun SAYS I must…”

Here’s a translation: “For my majesty knows he is divine, and I have done it by his command. He is the one who guides me. I could not have imagined the work without his acting: he is the one who gives the directions.” In other words, she doesn’t WANT to rule; she’s just doing what she’s been asked, and who can argue with that? She silences any haters, doing the written equivalent of walking out of a fire completely naked and holding dragons like she’s Daenerys Targaryen: “He who hears it will not say, ‘It is a lie,’ rather say, ‘How like her it is; she is devoted to her father! The god knew it in me. Amun, Lord of the Thrones of the Two Lands, he caused that I rule the Black and Red Lands as reward. No one rebels against me.” Damn, Hatshepsut!

And guess what? No one DOES rebel against her, despite the fact that she has no clear right to be there. There are no coups…none that have been passed down to us, anyway. Egypt accepts this lady king, even though they have a young man waiting in the wings. She has the priesthood in her pocket, and she’s obviously good at her job. But that doesn’t mean she won’t have to fight to stay there.

At first, she follows the example of female pharaohs before her in the realm of her PR department. Her etchings and statues look fairly feminine, with a few kingly touches mixed in. But as she gets a bit older, and as Thutmose III gets stronger and sexist jerks probably start whispering, she changes tack. “You know what? Screw it. Let’s put on that Hilary Clinton pant suit.” Her statues start representing her as full-on gentleman pharaoh: all signs of femininity are erased. She straps on a uraeus – a sacred serpent usually tacked onto the king’s headdress, an emblem of supreme power – and the long, pointy beard that’s synonymous with kingship. She rocks that crook and flail HARD. This move has nothing to do with identity politics or her fondness for facial hair, and everything to do with the Egyptian language of power. This is her chance to solidify her power. To say to the world, “This pharaohship is mine, and I deserve it. I’m more than man enough for this job.”

As pharaoh, she initiates an ambitious building campaign, creating jobs and making her cohort of priests very happy, constructing on a truly grand scale. She builds a great obelisk at Karnak: the tallest phallic symbol ever to be found there. She’s also the first pharaoh to build mostly in sandstone, a strong material that lets her create things that are wider and taller than limestone allows for . She builds her god-dad Amun something special at Karnak: a chapel, whose reddish-pink quartzite is the reason we call it the Red Chapel today. It’s there we find the deets about her coronation, and how Amun wanted to her rule, and so she DID. Several reliefs show her walking behind a god, with sort-of stepson Thutmose III walking behind her. That’s right: you stay behind me, Sir.

And then there’s her mortuary temple: one of the most beautiful, ambitious buildings in all of ancient Egypt. Since kings stopped building pyramids and started burying themselves in the Valley of the Kings, they’ve also been building mortuary temples. These are called Temples of Millions of Years – places where people can go and celebrate the pharaoh, and where a gal can create and curate her own personal museum, shaping how she wants her legacy to be remembered. Hatshepsut wants hers on the West side of the Nile, against some tall cliffs sacred to the goddess Hathor, extremely visible and right across from the Temple of Amun at a place called Deir El Bahri. This lady oasis is called Djeser Djeseru, or “holy of holies,” and it is EXTRA: even in our time, thousands of years on, it’s still one of the most wow-worthy monuments in Egypt. Designed by our man Senenmut, no doubt with much input from Hatshepsut, they create a place that’s incredibly visionary, with a grand symmetry that puts the Parthenon to shame. It has three levels and a giant ramp leading you up them: very wheelchair accessible, and not so steep as to make you regret how many times you’ve skipped the gym. This path is probably lined by sphinx statues, its first level is filled with exotic shrubbery. This is Hatshepsut’s Palace of Versailles, dedicated to her image. And she fills it with giant statues of herself. Because, obviously.

All this construction creates jobs, but it’s also really expensive. Hatshepsut’s solution? Go out and do a little warring! She takes her army south to strike some fear into the hearts of the Kushites, as they’re rich in gold and stone quarries and are always a little mad about Egypt telling them what to do. She dominates, bringing back tons of gold. Her wars are so successful that foreign kings to the north send her tributes, which are basically “we’re friends, right, please don’t invade me?” presents. But these adventures aren’t enough for Hatshepsut: in 1493 B.C.E, she organizes a rare and dangerous expedition to the mystical land of Punt. We don’t know exactly where Punt is – modern-day Somalia, probably? – but we do know that the place is famous for its riches. And it’s far away, by ancient standards: this trip will require a bunch of guys to drag ships in pieces 120 miles across the desert, then put them back together and sail across the Red Sea. This trip is a big deal – like, guys sailing across the Atlantic to test out whether the world is flat kind of A big deal. And it’s a real make-or-break moment for Hatshepsut, because if the trip doesn’t go off, it’s going to look like the gods don’t want her to be successful. And that might be all that needs to happen to see her kicked out of her pharaohship.

But it is a success: her band of explorers return with ships loaded down with ivory, ebony, giant balls of incense, precious frankincense and myrrh. They even bring back live incense trees and other exotic plants: this is the ancient world’s first known successful attempt at transplanting foreign fauna. She would have planted many of them at Djeser Djeseru. I sure hope she spent some quiet time frolicking amidst all that glorious myrrh.

But the good times can’t last. Hatshepsut dies after some 15 years serving as pharaoh. She’s buried not in the Valley of the Queens, but of Kings. But when archeologists first find her in 1903 in what they call KV20, her body isn’t in a sarcophagus (to see her mummy, go up to my list of sources and check out the Nat Geo article about her). Her body isn’t found until some 100 years later, left to the elements in some minor tomb…rude. Her name was almost erased from history. How did this happen?

While she lived, it seems like Thutmose III was happy – or at least, wasn’t game to challenge her - for what he must have considered his rightful place. But he enjoys a long reign once she passes, and he isn’t very far into it before he starts systematically removing her legacy, one building at a time. He smashes her statues, chips away at her etchings, and sometimes even clears her name off of carvings and replaces it with his or his father’s. Given that the ancient Egyptians believe that erasing someone’s name from the historical record messes with their afterlife, this is pretty cold. He even back dates his rulership to the year his father died, completely removing Hatshepsut from the chronology. Hey Thutmose III, your tiny man complex is showing!

We’re not sure what happens to Hatshepsut’s daughter, Nefrure: does she marry the new pharaoh? It would make sense, but there’s no sure record of it. Do they have any children together? No idea. Maybe he found a way to push her into obscurity, not wanting ever to be overshadowed by a powerful woman again. If only the rules had been different and Hatshepsut could have passed the torch to her own daughter. But in the ancient world, that was asking too much.

In her many years in power, Hatshepsut didn’t just hang on to her position by her fingernails: she owned it in a time when women weren’t meant to rule as she did. But don’t take my word for it: let’s let her define her own legacy in this quote from her temple:

“Every [god] says to himself: ‘One who will achieve eternal continuity has come, whom Amun has caused to appear as king of eternity on Horus’s throne.’ So listen all your elite and multitude of commoners. I have done this by the plan of my mind. I do not sleep forgetting, [but] have made firm what is ruined….I am come as Horus, the sole uraeus spitting fire at my enemies.”

Tragically, her name dropped away, lost in the sand until the 19th century. But now you know her – we should all know her. I’ve never been more ready to bend the knee.

You may know our next lady ruler from the famous bust of her very attractive head. It was discovered in 1912 by a German guy named Ludwig Borchardt. “Suddenly we had in our hands the most alive Egyptian artwork,” he said. “You cannot describe it with words. You must see it.” Even Hitler was obsessed with her: during WWII, the bust had to be hidden in bunkers and a salt mine to keep it out of his meaty hands. That guy was the worst, but he knew a good-looking head when he saw it.

When I first saw Nefertiti’s bust in Berlin – swan neck, killer cat-eyes, and her incredibly regal headdress – I thought she looked like a fashion model straight out of our century. She looks like someone you’d slyly ogle in a grocery store, not like an ancient queen of Egypt. But she was so much more than a pretty face, and lived a life more jam-packed with drama than a season’s worth of Neighbors.

We’re still hanging out in the 18th Dynasty, roughly 100 years after Hatshepsut. When you think of Egypt at its richest and glitziest, this is it. She is born into a country at the height of its powers, rich with gold and other goodies, full of grand buildings and huge construction projects. Amenhotep III has been ruling for many years – roughly 40, which is massive for ancient Egypt. This is the guy who married a foreign princess and still had enough energy to check out all of her 317 ladies-in-waiting, sending a note to her servant asking him to collect some.

But still, he has a main squeeze, Tiye (pronounced TEE), who is a major influencer. She’ll maintain her own correspondence with foreign dignitaries, and eventually her son will make her into a goddess. Speaking of: this couple has at least two royal sons together, but given the size of his harem, Amenhotep III has upwards of 100 kids floating around the place. Imagine trying to remember 100 kids’ names… “Hey, you! Product of my loins! Wait, don’t tell me…John. Anton? Number 12? Ugh, I give up. I’ll just call you son.” This pharaoh styles himself as a god, setting himself even more apart from everyone else in Egypt than many of the guys who came before him. Near the end of his reign, he also elevates Aten, a minor sun god. He makes this abstract sun disk his own personal deity, dedicating the hugest temple ever to him. He also gives himself a new, nifty title: “Egypt’s Dazzling Sun.” Remember Aten: we’ll come back to him later.

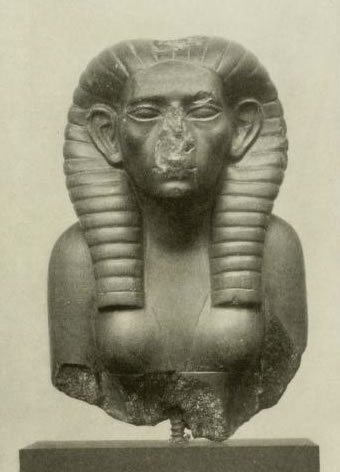

Boss lady Queen Tiye. This bust doesn’t represent her skin tone accurately: it’s this color because of age and the wood used in its carving. For more on her, go and check out the History of Ancient Egypt podcast.

Courtesy of Berlin Egyptian Museum.

Meanwhile, Nefertiti is off somewhere living a luxe life of wealth and excess, but not in the royal household. Maybe her dad was a court advisor named Ay. Or maybe, some say, she isn’t even Egyptian, but some princess from Syria. Horrors! We don’t know who her parents were, but we do know that they must have been important, as she’s given both a wet nurse and a tutor. It’s extremely likely that she grows up living like a Kardashian. If she does grow up in Egypt, she’s watching the royals line their swimming pools with gold bars, throwing money up into the air like they just don’t care, because they don’t. They’re as rich as Croesus. My grandma always used to say that, and I thought she meant “creases” – like, the kind you get in your pants. But Croesus is a real guy– a king of Lydia in Asia Minor who will use his mega piles of gold to build impressive temples. And even he would balk at this level of wealth. Amenhotep builds a pleasure palace at Thebes with a mile-long lake, along with a pleasure barge to cruise around on it. As the royal family’s carried through the streets during jubilee celebrations, they’re handing out hand-sized stone scarabs like party favors. This is a time of gold and glitter. Nefertiti must enjoy some real ragers

Things are going well until Amenhotep III gets fat and old and his chosen successor, Thutmose, dies suddenly. He quickly names his second son, Amenhotep IV, his co-ruler, and he steps in around 1353 B.C.E after his father’s death. His reign is pretty typical at first: he builds buildings, he paddles around on his dad’s pleasure lake. But then, some four years into his reign, he decides it’s time to wife up.

We don’t know how and why he chooses Nefertiti – perhaps she’s a foreign bride brought over to cement alliances. Maybe he’s known her all his life. Maybe he sees her across the room one day, draped elegantly next to a palm frond and is like, “Dammmmmn, girl! You fine.” Her name, which she might receive upon her marriage, DOES mean “The Beautiful One Has Come,” so…it’s definitely possible.

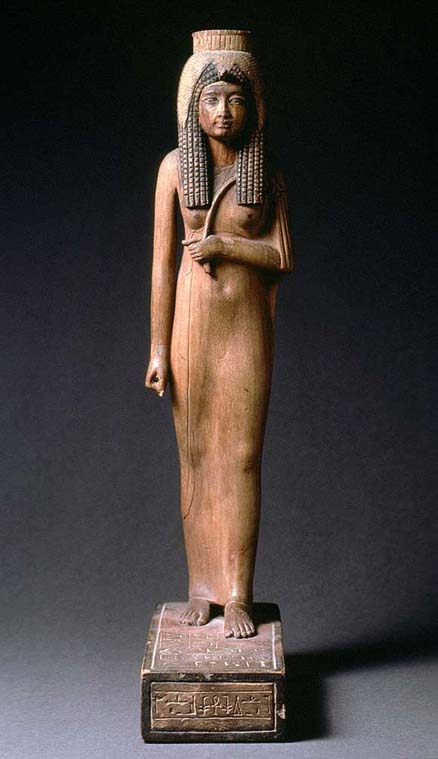

well hey, nefertiti.

Courtesy of Berlin’s Neues Museum of Egyptian History

So as young as 10 and as not-very-old as 16, Nefertiti finds herself endowed with titles like “Lady of All Women,” “Great of Praises,” and “Mistress of Upper and Lower Egypt,” the chief wife of the land’s richest, most powerful man. And that man has got some shocking ideas about where he wants his country to go. Surrounded by wealth, a country running smoothly, and no one willing to tell him no because he’s basically a god, damn it, he starts making some extremely bold choices. Some might even call them heretical.

He throws a massive Sed festival, or jubilee – way too soon, given that you’re not supposed to throw one for yourself until you’ve ruled for 30 years and he’s been around for, like, two minutes. This is just the first of many red flags. Because he’s undergone some kind of religious conversion that’s going to dominate the rest of his reign.

He orders builders to quickly construct new temples at Karnak for the festival: the deadline’s so tight they’re forced to invent a new building technique, using much smaller stone blocks than they’re used to. Does that sound like a recipe for a large-scale disaster? But then comes the big reveal: this festival isn’t actually for Amenhotep IV, but for Aten, that minor sun god we mentioned earlier. Because Aten is Amenhotep’s new BFF.

Imagine the priest’s horror on the day of the festival: their dread as they take in their pharaoh’s new-fangled symbols and outfit, and the artwork etched into the walls, which he says his god communicated directly to his brain. And this art is seriously avant-garde. The royal family’s features are elongated, stretched in an almost surrealist style, with extended bellies, exaggerated angles, and beams of light shooting over and through them. The look is…unique, and it isn’t doing Nefertiti any favors in the looks department. She’s probably checking them out on the festival day like, “Ugh…Did you have to post that one?”

But in it, her husband gives Nefertiti pride of place like no queen before her. She’s often represented at the same size as her husband: since size equals importance in ancient Egyptian artwork, it’s a big deal for her to be on par with her pharaoh. It also shows a scandalous amount of PDA: Nefertiti sitting on her husband’s lap, cuddling, even kissing. Woo: is it getting hot in this temple? Because these things are just not done.

While it’s clear that Nefertiti isn’t his only lady lover, she’s certainly important to him. He even writes his wife some racy love poetry: “And the Heiress, Great in the Palace, Fair of Face, Adorned with the Double Plumes, Mistress of Happiness, Endowed with Favors, at hearing whose voice the King rejoices, the Chief Wife of the King, his beloved, the Lady of the Two Lands, Neferneferuaten-Nefertiti, May she live for Ever and Always…” Notice how the poem puts her in the driver’s seat: he’s worshipping her. As is proper.

And as nice as that is, this whole thing rocks Egypt’s boat really hard. Because he’s not just obsessed with this minor sun god Aten: he wants to completely change his country’s mode of worship. He changes his name to Akhenaten (meaning “It is Beneficial to the Aten”) and more or less gets up and says the following: “Hey everyone! So, big announcement: the gods are dead. There’s only ONE god now. His name is Aten, and he’s the actual sun, and we only worship him. That’s cool, right? I thought so.” It’s hard to overstate how big a deal this is in ancient Egypt, where the sun quite literally rises and sets only if the pharaoh and his priests worship the gods correctly. This is the structure the whole country hangs its hat on: spiritually, economically, politically. Which makes this – perhaps the world’s first stab at monotheism - completely insane.

Amidst all this crazy, people have to be looking at Nefertiti with some serious “is this for real?” eyes. If you’re a Game of Thrones fan, think of the witch Melisandre telling everyone who will listen that there’s only the god of fire, and nothing else. Some people see it as visionary. But many see it as their leader going bonkers and deciding to join some crazy cult. Akhenaten’s changing his symbols, his temples…he’s even messing with the afterlife. And he’s making it illegal to worship anyone but Aten. Yikes.

Akhenaten makes sure to emphasize his solar fusion with Aten in any way he can. How does one worship a god who is literally the sun? Hello, sweaty ceremonies in open roofless courtyards! Priests have to stand out under the scorching desert sun and let the god’s light beat down on them, getting very sunburned and probably whispering mad smack about this whole business. The night may be dark and full of terrors, but the day is really hot and I’m starting to peel.

This isn’t just theologically troubling: it puts many, MANY people out of a job. Think of all those priests of Amun, the artisans who sell religious amulets, everyone involved in the religious structure: it’s a lot of people, often powerful people. They must be sputtering with rage.

But given that Egyptians don’t overthrow their kings often and there is no ancient Complaints Box, who knows how they really feel. We don’t know how Nefertiti feels about it, either. Is she totally down for this born-again ideology: does she even help inspire it? Or is she simply going along for the ride, trying to make sure her husband doesn’t steer their country’s boat into any whirlpools? Regardless, this new monotheistic system puts her in a unique position, given a kind of power that few queens have known before. She’s even given her own temple, which is filled with pictures not of her husband, but of her and her daughters. A place of ladies-only worship. Speaking of daughters: in their marriage’s first decade, Nefertiti manages to have six of them. Official artists are often making a big deal of her prolific fertility. And she’s like, “Dang, y’all. I’m fertile as hell.”

Things get weirder from here. After having a prophetic dream, Akhenaten decides to move the capitol out of Thebes to a remote desert site called Amarna. He builds his dream city there with the quickness, far away from all of those old pesky gods and their power-hungry priests. This is a revolution.

This move is a two-sided, culty coin situation. On one side, you have a religion defined by light and love and a new city full of new ideas; on the other, you have elitism and terrible labor practices, where the people building the city are malnourished and treated poorly. Of course, he makes sure there are plenty of airy courtyards and temples without roofs so we can all get sunburnt by the god together. He dubs it Akhetaten, or “Horizon of the Aten,” and tells the courtiers they’d better settle in. He has to give them lots of land and high positions to get them there, but whatever.

In this new world, we see a TON of artwork dedicated to the royal family. It’s like Akhenaten wanted the world, present and future, to know how crucial his queen and children are to his power and his belief system. They show her not just as her husband’s arm candy, but as a leader in her own right: driving her own chariot and smiting her enemies. Get it, Nefertiti! Ahkenaten and Nefertiti make sure to ride through the streets in their golden chariot as often as possible, no longer servants of the gods, but gods themselves. Maybe even co-rulers, at that.

But things aren’t all golden chariots in Nefertiti’s life. Her husband has a harem that she has to manage, and one woman – Kiya, also called Monkey – is given an unprecedented title by her husband: that of Greatly Beloved Wife. And Nefertiti’s like, “excuse me what now?” Monkey’s quick to pass out of the records, and we don’t know what happens to her. Who knows…maybe Nefertiti fed her to the crocs. And then, two of their much beloved daughters together actually marry dear old dad. So, yes: she’s now sharing a marriage bed with her husband and their TWO YOUNG DAUGHTERS. Blehhhhhh. But what’s a girl to do, as she starts to get older and her husband gets cozy with their offspring? Pull a Madonna and reinvent herself.

Around Year 12 of Akhenaten’s crazy rein, Nefertiti disappears from the records. Maybe she dies of some ancient world plague. Or MAYBE, when a new co-ruler suddenly appears, it’s actually our girl Nefertiti. This co-rulers name is incredibly hard to pronounce – Ankhkheperure Neferneferuaten? Oh my. If it is Nefertiti – and, let’s be honest, that second half of her new same sounds a whole lot like her last one - then she has done what no queen has done before her: rules equally beside her pharaoh husband, and with the same kind of power.

It’s hard to know how and why this whole thing transpires: maybe Akhenaten feels he needs her to keep the nobles on his side, and she’s the better politician. Maybe she’s the only one he can trust. Or maybe she’s just really good at ruling, and Aten only knows that her husband needs some help keeping things going.

Then tragedy strikes; two of their daughters die. In Year 14 of his reign, Akhenaten’s great mother Tiye dies also. And that’s when Akhenaten really starts losing his marbles. He not only doubles down on his worship of Aten, but orders workers to go around chipping the images of other gods like the beloved Amun off temples, tearing away the plural word ‘gods’ wherever they see it written. If you’re a polytheistic believer, as most of the populace probably is, imagine walking around with amulets tucked under your collar, terrified someone will rat on you? Things are getting Handmaid’s Tale level dark.

But then they get darker, quite literally, when a total eclipse appears in the Nile Valley in 1338 BCE. It takes the sun out of view for more than five whole minutes. Imagine Nefertiti looking out the window, wondering if her world is ending – if maybe this whole crazy gamble on a sun god wasn’t the visionary move she may have thought. Imagine how you’d worry that the people would take it as a sign and revolt against you.

When Akhenaten finally dies at around age 50 – not of poison, apparently, which is sorta shocking – Nefertiti and her remaining kids are left to pick up the pieces of the broken empire he’s left behind.

But first, a new pharaoh is chosen: one Ankhkheperure Smenkhkare. Does that first name sound familiar? It’s the same one we think Nefertiti was just using as part of her co-regency name. So, of course, some historians wonder…is this guy actually Nefertiti, reinventing herself again? Does she transform herself so completely after her husband’s death that she’s able to hold onto her power? Some argue that because this pharaoh has wives on record, he must be a man. But what if those wives – Nefertiti’s remaining daughters – are actually just her working partners? While she rules as pharaoh, her daughter Meritaten rules as queen beside her, keeping proper balance in place. It’s kind of wild to think about, this queen rising out of her husband’s crazy ashes with her lady posse and being like, “Move over, boys. Let me show you how it’s done.” But Egypt is in real turmoil, and someone needs to put it right. Why not her?

This image is commonly taken to be Smenkhkare and Meritaten, though it may be Tutankhamun and Ankhesenamun. Ancient history gets very confusing.

Courtesy of the Neues Museum, Berlin

She sets to work, promptly moving the capital back to a major city, rehiring priests, and basically saying, “MK, everybody, polytheism’s back on. You can thank me later.” She’s also trying to make sure her remaining children don’t grow up to be complete nut jobs. That includes Tutankhamun: maybe you’ve heard of him? We don’t know for sure that he’s Nefertiti’s son: he could be her grandson, or the son of another one of his wives. But he must look up to Nefertiti as he grows, trying to grapple with what it means to be a ruler.

This potential Nefertiti is only pharaoh for a few short years, and then she disappears from the records again in a puff of golden, glittery smoke. There’s so much we just don’t know about how her dramatic story goes down.

Even her legacy is steeped in drama. When her bust is discovered in 1912, everyone is obsessed with this Queen of the Desert. But we don’t actually know where she’s buried. In the Valley of the Kings, perhaps, but where? Some think that a mummy called the Younger Lady, discovered in 1898, might be her. Though we hope not, given that she’s missing an arm and someone seems to have done mean things to the body, messing with her afterlife. Not even her incredible bust is sacred. Some recent CT scans of Nefertiti’s head show another, less flattering layer of stucco underneath, with a bump in her nose and wrinkles around her eyes. She may have been one of the earliest celebs to undergo serious photoshopping. What might Nefertiti think of all this hot gossip? “What’re you so obsessed with my face for? Wrinkles or not, we both know I’m fine.”

Most people think we still haven’t found her body. But in 2015, a British Egyptologist will make an exciting claim: that maybe when King Tut died suddenly and was buried in his now-famous tomb, it was really just the front portion of a larger tomb meant for Nefertiti. Maybe she’s been hiding behind the walls! It was a tantalizing idea, but in 2018, ground-penetrating radar suggested there was nothing lurking behind King Tut’s walls. Which is sad, because until we find Nefertiti, we’ll only ever be able to guess at how much she accomplished.

Here’s another tantalizing idea put forth by Kara Cooney in her book When Women Ruled the World: that King Tut’s famous sarcophagus – the one you think of when you think of Ancient Egypt – was actually meant for Nefertiti. Perhaps it’s her face we’ve been staring at all this time, calling out to us through the millennia, trying to tell us the story of her awesomeness.

Let’s hop over one or two generations to our next lady – but before we get to her, let’s talk about what’s going on in Egypt, since things have changed since Nefertiti partied down. The people in charge have gotten wary of both of heretical kings without any checks on their power and royal women with any power at all. Thanks to crazy bag Akhenaten, the powerful elite families will never again blindly trust their leader. We see a conservative backswing toward powerful male warrior kings, and we also see far fewer incest brother-mother-wife situations. This is greatf or girls trapped in the incestuous harem – go forth, ladies! Breathe that fresh air! Have an affair with a ferryman! – but it also means they don’t have the same power or potency. For better or worse, keeping it all in the family is what’s let all of our ladies so far move up the political chain. But now we see a series of powerful pharaohs with truly giant harems and obscene numbers of children, which creates its own problems, as we’ll see.

The Rammeside period is dominated by guys called Rameses, starting with 1 and going all the way to 11. These guys kick ass, take names, and bring foreign slaves back to Egypt as spoils of war. This is where our image of the enslaved in Egypt come from.

These guys also have many, MANY children. Ramses II, also known as Ramses the Great, has some 162 of them, making him the 10th most prolific dad on historical record. Though he’s got nothing on Genghis Khan…that guy slayed.

Ramses still has a main wife, Nefertari, whose name means “The Loveliest One of All.” This successful queen consort marries Ramses II before he ascends to the position of pharaoh, suggesting theirs is at least in part a love match. Despite his busy sex schedule, Ramses the Great makes sure to celebrate his main squeeze by building giant statues of her all over Egypt, including a temple all her own down south near Nubia at Abu Simbel, where he installs statues of her at a truly grand scale: around 30 feet tall, even taller than her husband. Her beautiful tomb in the Valley of the Queens showcases her many talents: she stands before the god of knowledge, Thoth, proclaiming she’s a scribe: an academic accolade not often given to women. She corresponds with a rival Hittite queen, becoming a kind of foreign ambassador. In sum: she wields some serious behind-the-scenes power, no question. But she doesn't have the same paths to power as the royal women before her.

While before, pharaohs tended to leave most of their children’s names off of official records until one was chosen as the next pharaoh, this guy publishes their names all over. Which is nice, right? Look at Ramses and his billions of children, holding hands and spinning in circles! Except that naming them gives his kids a kind of power that threatens the establishment. This is why Merneith and her Dynasty had to kill a bunch of people each time a new pharaoh was crowned. Suddenly you have a situation where all 50 or so sons are encouraged to shout their connection to the pharaoh from the rooftops, and thus ALL consider themselves entitled to be his next in line. 50 boys competing for the top spot: this’ll end well, surely!

And then Ramses the Great makes things worse by deciding to live precisely FOREVER: he makes it to the ripe old age of almost 100. It must have been all of that regular harem exercise! And though the Egyptians are not ones to write down anything juicy about conflict in the royal household, there are signs of feuding between Ramses’ sons. In 1200 BCE., he names some 12 of these guys his successors…and then, because this is the ancient world, they all end up dying before they can inherit. That’s how 13th runner up son, Mernaptah, ends up becoming pharaoh of the Two Lands. And he’s got serious problems to deal with. One of them is that he’s a little old to be taking on the kingship, which depends upon him having legitimate heirs.

But also, a bunch of what are called the Sea Peoples are coming to Egypt in massive numbers: evacuees from the North looking for a better life. But they’re not just showing up and asking for asylum: they’re invading Egypt. This is the situation our main lady, Tawosret, is born into. From now on, foreign invaders will never leave Egypt alone again.

Just like his father before him, Mereptah doesn’t die until he’s 60 or 70, having managed to outlive most of his sons. But one remains: his name is Seti-Merneptah, otherwise known as Seti II. He, like his dad, is fairly long in the tooth by the time he comes to power: a little old to be playing the Bull of Egypt. So though he already has a wife, probably the same age as he is, he decides he’ll need to take a second, much younger one to make some kingly babies with: that’s where our gal Tawosret comes in.

From the beginning, this must be a weird situation for her. She’s one of TWO Great Royal Wives, and she’s the younger one: this has to lead to some awkward teas and backdoor dealings with the pharaoh’s other wife. Maybe they keep things separate, heading up different harems – because of course the pharaoh has several. Or maybe they pretend to support each other while they scheme behind each other’s backs. She must be working hard to get a bun in the oven, assuring her place in the scheme of things before her elderly husband croaks. But it doesn’t seem like they ever manage it.

There’s external warring, too. While Tawosret’s hubby is ruling from Pi Ramses WAYYY up in the Nile River Delta, in the South at Thebes there’s this other guy who has decided he doesn’t like the way the pharaoh is ruling. And since he’s related to Ramses the Great – I mean, who isn’t? – he claims himself as king of the South. That’s what happens when you have a million children, Ramses. This pharaoh, Amunmesses, has military might and control of Nubia’s gold mines behind him. The country’s plunged into one of its first civil wars.

In only a few years, this upstart Southern king is defeated, but it leaves the country in a bit of a mess. So Seti II does what any pharaoh would do – starts defacing anything his rival ever built and scrubbing his name from the records. He also appoints someone to help him get things back in order in the south: a non-royal guy named Bay. As “The Great Overseer of the Seal of the Entire Land,” this guy has control of the entire treasury, and he’s sent down to Thebes to consolidate the king’s power. While he’s at it, he removes a carving of Seti II at Karnak and puts one up on himself instead. The rumor mill is aghast. “Okay, so #1, he isn’t the pharaoh. #2, he isn’t even royal. I heard he’s not even Egyptian. He sure isn’t MY bae.” Yet he’s carving his name into the stone like he owns the place? A definite sign of troubles of come.

Enough about men and their swordplay. Seti II dies younger than his forebears, and his death plunges the land in to a succession crisis. The next pharaoh, named Siptah, is very young and has some kind of mysterious disability. We don’t know where he came from, but Tawosret certainly didn’t produce him. She has no clear claim to the throne anymore. Regardless, she pulls a classic Hatshepsut, stepping in to rule as his regent. She also takes up that old standby position, God’s Wife of Amun, perhaps to try and prove that she does indeed have the power to be regent.