Pour Us Another: The History of Women and Beer, from Ancient Past to Present

We’re wandering through an ancient Egyptian village.

There’s something on the air: it’s a scent, both sweet and savory, full of sunlight and grain. Is someone baking bread? There’s steam floating out a window, so you peek in. Ah, now you see: someone’s brewing. Someone stands behind a clay pot, making beer.

Who is this brewer you’ve got in your mind’s eye? Likely he’s got a beard and is wearing time travel inappropriate flannel. But you’re going to have to shift that mental image, because the brewer we’re looking at…is a woman. In fact, for most of history, women were primarily the ones who brewed beer. For millennia, brewing was overwhelmingly a woman’s game. You can’t research beer’s history without stumbling across female brewers.

So why, when we conjure up an image of a brewer, is it a dude we always picture? How did beer, both the brewing and the drinking, become such a “man’s drink”?

To find out, we’ll explore how beer was made in the ancient world, then hop forward through time, following a particular story through history: the relationship between women and beer. And their connection to one of the world’s oldest beverages will probably surprise you; it may even change your relationship with that IPA currently sitting in your fridge.

Pack your beer mug, a pointy witch hat, and get ready to party.

my resources

BOOKS

Atlas of Beer: A Globe-Trotting Journey Through the World of Beer. Nancy Hoalst-Pullen and Mary W. Patterson, National Geographic Books, 2017. I actually edited this book, and credit it with getting me interested in the subject. Highly recommended if you like beer, travel, and history!

Beer in the Middle Ages and the Renaissance. Richard W. Unger, University of Pennsylvania Press, 2004.

The Oxford Companion to Beer. Edited by Garrett Oliver, Oxford University Press, 2011.

PODCASTS

“Witches’ Brew: How the Patriarchy Ruins Everything for Women, Even Beer.” DIG: A History Podcast, Oct. 2018.

ONLINE

“Traces of 13,000-Year-Old Beer Found in Israel.” by Brigit Katz, Smart News, Smithsonian Magazine. September 2018.

“Our 9,000-Year Love Affair with Booze.” By Andrew Curry, National Geographic, Feb. 2017.

“Discovered: The Tomb of an Ancient Egyptian Beer Brewer.” By Megan Garber, The Atlantic, Jan. 2014.

“Egyptian Beer Brewing; Practices, Uses, and History.” Jason S. Lambracht, Oct., 2014, MSU.

“2,550-Year-Old Celtic Recipe Resurrected.” Bruce Bower, Science News, WIRED, Jan. 2011.

“Beer in the Ancient World.” Joshua J. Mark, Ancient History Encyclopedia, March 2011.

“According To History, We Can Thank Women For Beer.” By Courtney Iseman, Food & Drink, HuffPost 2018.

“The Dark History of Women, Witches, and Beer.” Scotty Henricks, BigThink, Mar. 2018.

“Women and Beer: A Forgotten Pairing.” By Allison Schell, National Women’s History Museum, May 2017.

“Hildegard von Bingen.” Craft Beer & Brewing.

“Brewing in the Seventeenth Century.” National Park Service, Feb. 2015.

“Beer: Thomas Jefferson’s Monticello.” Monticello Museum Research & Education.

“Stats.” Women in the Craft Beer Industry.

“Shifting Demographics Among Craft Drinkers.” By Bart Watson, Brewers Association, June 2018.

“#WeAllLoveBeer Uses Hidden Camera Footage to Show That People Can Be Sexist Even When it Comes to Beer.” Claire Warner, Bustle, Nov. 2015.

“The Spirited History of the American Bar.” By Rebecca Dalzell, Smithsonian Magazine, Aug. 2011.

“A Potted History of Women in Bars.” By Elise Godwin, Broadsheet, March 2019.

“Male-oriented Advertising is Putting Women Off Beer.” By James Beeson, The Morning Advertiser, May 2018.

“Beer Ads That Portray Women As Empowered Consumers, Not Eye Candy.” By Zach Schonbrun, New York Times, Jan. 2016

“If You're Toasting To Health, Reach For Beer, Not (Sparkling) Wine.” Alastair Bland, The Salt, NPR, Dec. 2014.

episode

to learn more about Pink boots:

Pink Boots Society, Australia.

i’m having a vision…of hops going into beer!

Hildegard of Bingen, one of the first people to write about the benefits of adding hops to beer. Illumination from the Liber Scivias showing Hildegard receiving a vision and dictating to her scribe and secretary, from Wikicommons.

TRANSCRIPT

I add and delete a bit while recording, so this won’t match the episode on the airwaves exactly. please excuse any typos or wierd formatting: i do my best!

Beer has been around since we humans first put down roots and started farming, but we developed a taste for fermented things long before that. Our primate ancestors were tempted down out of the trees for fermented fruit: it was simple to find, full of easy calories, and made us feel all warm and tingly. I can just see the thought process: “Rotting fruit, you say? Mmm, yes…party time.”

Around 10 million years ago, our last common ancestor of African apes saw a mutation in their ADH4 gene, which created an enzyme that let them digest ethanol some 40 times faster than before. The so-called “drunken monkey” hypothesis suggests that our bodies evolved to deal with alcohol, perhaps because it gave us some kind of survival advantage. This we know for sure: we’ve been enjoying alcoholic fruit juice for pretty much as long as we’ve existed.

Grain cultivation took off in Europe during the Neolithic Period starting around 8000 BCE. Grains are one of only three ingredients needed to make beer, along with water and yeast. So where there’s grain, brewing can’t have been far behind. Until recently, we didn’t have any archeological evidence of barley beer until 3500 BCE at a place in modern-day Iran called Godin Tepe. But in 2018, researchers at Reqefet Cave in what is now Haifa, Israel, found evidence of a brewery dating back 13,000 years. They analyzed three stone mortars there, all of which held starch residue and microscopic plant particles that make researchers fairly certain they were used to brew beer. In this cave, the semi-nomadic Natufian people not only buried their dead on beds of flowers, a condition I’ll be writing into my own will for sure, but also brewed beer to send with them into the afterlife. Which gives weight to an idea that’s been floating around for quite a while: that it was our thirst for beer, perhaps just as much as our taste for bread, that pushed us to stop all our nomadic wandering and settle down to an agricultural life.

We were drinking beer long before we started writing down recipes – or anything else, for that matter. A steady supply of grain-dense, nutrient-rich beer may very well have helped foster written languages and art. It spawned exploration and informed religious ritual. You could say that beer helped jump-start some of the world’s first great civilizations.

More and more evidence of ancient brewing is cropping up around the world: it was developed independently in China, the Middle East, and South America, imbibed (we think) in religious ritual and around the casual dinner table. When people moved, they took their brewing practices with them. We’re not talking about a luxury item here, either. Everyone drank it – young and old, male and female, priest and serf.

But who actually invented it? We have no idea, but it probably happened by accident. Maybe someone was making some bread and left a bunch of wet grains out on the sill overnight. That’s when wild yeast – those tiny, single-cell organisms always floating on the air all around us – got in and started performing a special kind of magic, transforming sugar into alcohol. Imagine being the adventurous farmer who looked into that bowl of wet grains that smells like barnyard on one of its less-clean days and saying: “hmm. I mean, no sense wasting it.” Delicious?

Here’s a quick rundown of the brewing process, which at its heart has barely changed in all this time.

Step one: Mashing.To make beer, you need just four ingredients: grains, water, yeast, and hops. Although if you’re an ancient brewer, hops are optional. Gather your grains, then soak them in a hot water bath. That’ll wake up the enzymes that change starches and proteins into fermentable sugar. The result is a sugary water called wort. Yup: that’s W-O-R-T. It sounds better in an Australian accent (have Paul say it).

Step two: Lautering. You’ll separate the wort from the grains in a big pot, sometimes called a lauter tun. From there, you’re going to sparge it: and again, Australian: SPARGE. Which is a fancy term for rinsing the grains to get as much sugar out of them as possible.

Step three: the Boil. Now we’re going to boil the wort, stirring it like the witches we are. The ancients would have added whatever bittering plants they had on hand at this stage, but we’ll probably add hops: for bitterness, add some at the beginning of the boil; for flavor and aroma, near the end. Okay, sweet. Now…

Step four: The Whirlpool. Our wort will spend some time in a jacuzzi…just kidding. Our resident brewer Mr. Exploress just gives the wort a little stir, creating a hand-made whirlpool, which separates out any hop fragments and protein strains.

Step five: Chilling. We’ll cool the wort down as fast as we can. When the temperature is low enough, we’ll add in our yeast.

Step six: Fermentation. Pour some yeast into the brew, where it will proceed to throw a big ol’ rager. (PARTY TIME!!!) It eats away at the sugar in the wort, making many happy blurping noises, producing alcohol in the process. Once the yeast has eaten all the sugar and is nursing a wicked hangover, we’ll filter the beer – or not, up to you. Put it aside to condition a while, or pop it into a keg or a bottle, where it’ll most likely be carbonated.

Step seven: Enjoy.

To find out more about brewing, I went to Colonial Brewing in Melbourne, Australia, to talk to a modern-day lady brewer, Flora Ghisoni. I asked Flora what she thought ancient beer would taste like. Please forgive the audio quality; think of the seagulls and beeping trucks as a bit of charming ambiance:

“I guess beer that was spontaneously fermented was probably a bit sour. I also imagine they would be flat, as at that time, they weren’t able to catch CO2 and keep it inside the beer. So yeah, completely different… [this part is from the section about brewing in countries that forbid it]…It’s basically fermenting any kind of sugar and turning it into alcohol, and that makes the whole spectrum of what result you can get very wide.”

Why was beer so popular? Because before we understood a whole lot about sanitation and bacteria, we DID understand that local water drunk up straight often made us sick—but beer didn’t. Because beer requires you to boil your water, killing any nasty bacteria. Plus ethanol is toxic to other microbes, which makes it antimicrobial. While olden-day brewers wouldn’t have understood the mechanics, they knew that beer was safer for regular consumption. And in ancient times it was drunk unfiltered, thick and porridge-like, full of things that were good for you: easy calories and B vitamins like folic acid, niacin, thiamine, and riboflavin. When you think about how bad the ancient diet was for many, and how scanty, beer was both crucial and convenient. They were drinking the equivalent of ancient bread.

Ancient Egyptians often get credit for inventing beer, but they didn’t. What they did was brew the first stuff we time travelers would recognize as beer. And it was considered quite healthy: a great remedy for many of the things that might ail you. The Ebers Papyrus says that half an onion and the froth of a beer are “a delightful remedy against death.” Egyptian medical papyri catalogue some 17 different kinds: dark beer, friend’s beer, heavenly beer, sweet beer. They’d sometimes sweeten it with dates or honey, or add some red dye if it was for a festival. One thing’s for certain: none of them were carbonated, and none had any bittering hops. They drank it out of bowls or goblets, and it was so thick with grainy, malty goodness that you had to drink it through a straw. The ancient Sumerians invented the straw for this very special purpose.

Most of your everyday stuff was low alcohol, sessionable enough to be enjoyed by all. But for real, time traveler: don’t break out the beer bong. This stuff is more like porridge than anything you’ve ever enjoyed in a beer garden. Mmmm…lumpy. Chugging not advised.

Beer also served as currency. The guys who built the pyramids were often paid in beer. And if the overseers missed a pay day, they might just have a revolt on their hands . It can be sacred: Egyptians offer it up to their gods. And it was a popular item to take with you into the afterlife: it is a staple in any given Egyptian tomb. King Tut was buried with jugs of it. There were even royal beer brewers, whose status was lofty enough that some of them had fancy tombs of their own. Take Khonso-Im-Heb, the head brewer for the court of Amenhotep III, all-around lady slayer and Nefertiti’s father-in-law. His tomb is covered in images of beer production, which he apparently brewed in honor of the goddess Mut. One of fancy lady pharaoh Cleopatra’s biggest mistakes during her reign was imposing a tax on beer – perhaps the first in history – which caused considerable public outrage. Which tells you how much beer the public must have been drinking. She claimed it was to curb public drunkenness, but it was probably to fund her war with Rome. But…more on her later.

Beer was beloved so much that it wasn’t just made at home, but on an industrial scale. One site at Hierakonpolis had the capacity to make some 1,200 liters of beer a week.

The Romans and Greeks were big fans of wine, and tended to consider beer a barbarian drink. As Martin Luther will say much, MUCH later: “Beer is made by men, wine by God.”

Ancient Greek writer Xenophon gives us this review of a Mesopotamian beer he tried: “the beverage without admixture of water was very strong, and of a delicious flavor to certain palates, but the taste must be acquired.” Subtle, Xenophon! But as Rome expanded its borders, they encountered people who lived on the beverage. And since Roman soldiers out on campaign often found themselves without a steady wine supply, they learned to embrace it. They even started brewing it themselves, calling it cerevisiae, a word that probably has Celtic roots.

For the ancient Celts and Gauls, beer was almost sacred. At a 2,550-year-old Celtic site in Germany, archeologists have found evidence that they soaked barley in specially dug ditches until it sprouted, then dried them out by lighting fires at the ends of the ditches to roast the grains, giving them a dark and smoky taste. They then probably added spices like mugwort or henbane, which is supposed to make beer more intoxicating. If the Celts liked one thing, it was a drunken party. Snobby Roman emperor Julian described it as smelling “like a billy goat.” Mind your manners, Julian. Some beers are supposed to smell like that!

Here’s the thing: back in Egypt, beer eventually became commercialized. You needed a license to do it, which probably blocked women from becoming professional brewers. But go to any farmhouse in ancient Egypt and you’re likely to find a lady brewing at home. Because in all of these places, brewing was primarily done at home. And it was overwhelmingly a woman’s game.

Model of a woman grinding grain, which she’ll use both to make bread and to brew beer.

From Egypt, First Intermediate Period/early Middle Kingdom, 2134-1991 BCE. Courtesy of Los Angeles County Museum.

A WOMAN’S PLACE (IN BREWING)

In our early beginnings, with the men out hunting down things with tusks and many teeth, women were left behind to gather herbs and get to brewing. In the ancient world, there were no local bottle shops to stop in at, and if you were the average lady, no courtly brewer was making it for you. Brewing was considered a domestic duty: something akin to baking bread and preparing the meals. That made it primarily a woman’s business.

There’s a site in modern-day Syria called Tall Bazi: each house in this ancient town perched along the Euphrates River contains a 50-gallon clay jar, sunk into the floor, where archeologists found traces of barley. The women of these houses used their cauldrons to operate their own tiny breweries. They fermented whatever fruit and wild grains they happened to have on hand, which changed depending on locale: agave, bananas, birch tree sap, corn, cassava, horse milk. Mmmm. Sometimes, if they had any extra, they’d even sell it to bring in extra income.

Remember how that ancient Egyptian brewer dedicated his brew to the goddess Mut? It’s telling that female goddesses are all up in the brewing business. The ancient Sumerian god of beer is a goddess named Ninkasi: she even had her own hymn, which is also the world’s oldest surviving beer recipe. The deity of drinking is also a woman, named Siduri. The Epic of Gilgamesh, the oldest written story on record, includes an alewife in its pages. And in it, the hero Enkidu takes council from a prostitute named Shamhat, who teaches him to drink beer.

Egyptians have a beer goddess, too: Tenenet, who watches over brewers and the quality of their product. But many of their goddesses are tied to beer. Take Sehkmet: that lion-headed goddess who goes around eating people until the god Ra spills some red-dyed beer out for her, which she slurps on up and then passes out, transforming into the gentle goddess Hathor. There’s a festival that commemorates this event, called the Tekh Festival, aka the Festival of Drunkenness. Egyptologist Carolyn Graves-Brown suggests that artwork depicting the festival ties drinking to “travelling through the marshes,” which may well be a euphemism for horizontal love time. An inscription at one of Hathor’s temples from 2200 BCE may say that: “The mouth of a perfectly contented man is filled with beer.” But it was mostly women who brewed and served it. The Mesopotamian Code of Hammurabi, a comprehensive code of law dating to around 1754 BCE, is full of rules about beer. And every one about taverns is gendered: every tavern owner is listed as ‘she’.

Women often brewed and baked together, sending their grains on different journeys, destined to end up on a plate and in a glass. In ancient Babylonia, brewing equipment was often given as part of a girls’ dowry. Thus beer and brewing was a regular feature in the ancient lady’s life.

So…what changed?

In Europe, with the fall of Rome and the rise of Catholicism in the Middle Ages, we see beer move from women’s kitchens to behind the cloister walls of abbeys, where it was brewed and tinkered with mostly by men. By the 11th century, they’d turned it into a profession, brewing beer for themselves, but also selling it to passersby.

But before that, in beer-loving places like Ireland, Scotland, and the lands we now call Germany, beer was brewed almost entirely at home by women, both for their family’s consumption and as an important way to make some extra income. In what we now call Finland, women made a beer called sahti with hops, juniper twigs, barley, and rye all smoked in a sauna. A very attractive Baltic and Slavic goddess named Raugutiene protected beer, and we think the Vikings only let women brew. By the mid-1300s in England, about a third of village women and half of all households brewed to make a little money. As Shakespeare said:

“ She brews good ale, and thereof comes the proverb, Blessing of your heart, you brew good ale.”

Many alewives brewed outside, stirring their cauldrons all afternoon long, throwing in all sorts of mysterious herbs and spices. When the beer was ready, they’d tie barley stalks to the end of a stick and hang it, broomlike, over their door. They wore a pointy felt hat both because it was fashionable and because it helped people see them over the crowd on market day. They kept cats around, too, as where there are sacks of grain, there are always mice, and unlike the ancient Egyptians, they didn’t think their poop had any medicinal properties, thank you. Wait, is this a brewer we’re talking about, or a witch? Hard to say. Which is why some think alewives are partially responsible for giving us the traditional image of a witch we’re all fond of today.

For alewives, brewing was not a get-rich-quick scheme: it was highly regulated, women were frequently fined, and probably because it was a woman’s market, the pay was bad. And there was a dark side to the whole business. Probably because they wanted to control the sale of beer themselves, medieval men loved to rain shade all over alewives. They called them liars and cheats, frequently accusing them of overcharging for inferior brew. But it gets worse. They were accused of tainting their beer, putting all sorts of grossness in it. These women weren’t just liars, but prostitutes and witches. If there’s one thing you don’t want to be accused of being in this or perhaps any time, it’s a witch.

A popular cartoon by C. Johnson, London in 1793, of an alewife character called, charmingly, “Mother Louse.” Sometimes women who hustle just can’t catch a break.

Courtesy of the Wellcome Collection

It’s around this time we start to see female brewers portrayed as both jokes AND a threat to a community’s moral fiber. A temptress who was also a beer seller featured back in Gilgamesh’s pages, and here we are again, in the 14th century with monk John Lyndgate’s The Ballad on an Ale-Seller, in which he calls an alewife someone “who uses her charms to induce men to drink.”

They’re shown with thick necks and mole-covered faces, dirty and not to be trusted, making them easier both to shut out and control. Brewing beer, and openly selling it, became dangerous.

Let’s hop on our brooms and fly away from that unfortunate turn of events, just for a minute, and talk about some of the ingredients we’re brewing with. Bear with me: this is lady related, I promise.

Before hops made their way into beer, there was gruit: a potent mix of herbs and spices that varied depending on where you lived. Alewives used all sorts of things, both fresh and dried: marsh rosemary, yarrow, juniper, heather. It was considered medicinal, and probably added some aroma and bitterness. Watch out, though, because some of these little additions might make you hallucinate, put you in an amorous mood, or give you extremely weird dreams.

The hop plant is a sticky vine called Humulus lupulus, a close cousin of marijuana, but without the stuff that makes you hallucinate. It produces cone-shaped flowers which, fun fact, only come from the female plant. They can be added into beer fresh, or dried and made into pellets. One of the first people to describe the potential medical benefits of hops, particularly when thrown into some beer, was a badass 12th-century abbess in Germany named Hildegard of Bingen. Besides being a composer, philosopher, and polymath, she was also a keen student of medicine. In her landmark medical book, she wrote about hops’ preservative qualities, but also how they increase melancholy: which is saying something, given that most monks were prescribing them to pick up people’s spirits. We know now that hops are a sedative, great for helping relax our nervous systems. Way to be a legend, Hildy.

Hello, lady hop. Let’s get to brewing.

Taken by LuckyStarr, Wikicommons.

Hops got into beer in the 16th century, primarily because it was handy for keeping it from going bad. Because beer could now be kept fresh for longer, it could be made in much bigger quantities and shipped further afield.

And so it is that hops helped bring about the alewife’s demise. Here’s Flora again. “I think once it became industrialized, then it became more of a man’s job. Because it wasn’t a cooking task anymore.” And when it stopped being a cooking task and showed promise as a major money maker, men were quick to step in and take over. Brewing suddenly required big operations and expensive equipment: beer just got too expensive for the average small-time female brewster to afford, and they didn’t have the support to do it.

Men established brewer’s guilds, which were meant to protect brewer’s interests. But these, and the laws they helped get into writing, tended to shut women out of the game. In Bruges in 1447, a brewing association met to protect themselves from “innkeeper, woman, and provost.” One 1540 law in the city of Chester in England banned women aged 14 to 40 – so, anyone with the potential of bearing children – from practicing as alewives. I mean, bear children AND hold down a job? No woman could handle it!

Later, the Industrial Revolution also played its part in putting the final nail in the alewife’s coffin. As brewing went commercial, it became harder for women to break in.

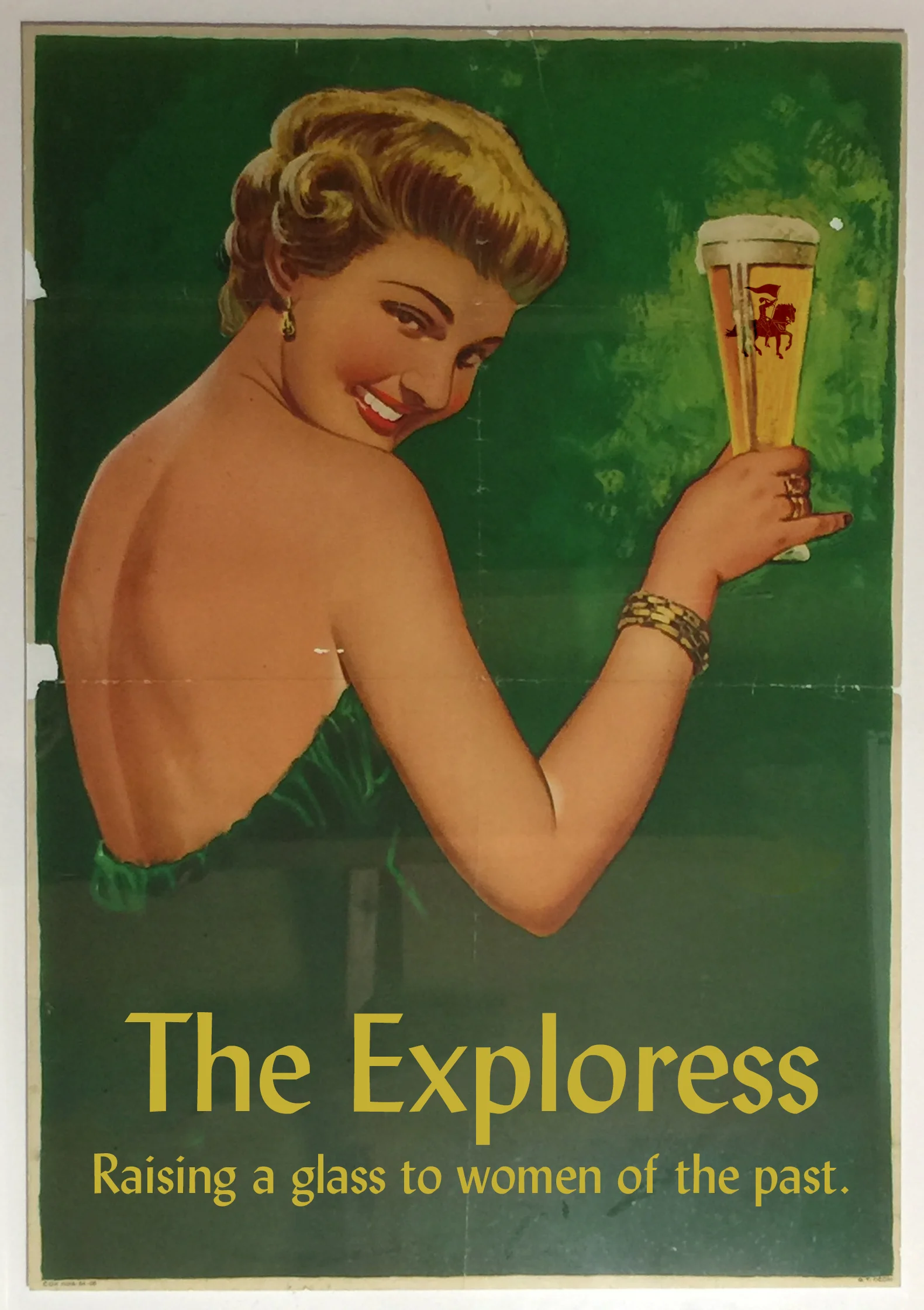

Women are very often seen in beer advertisements serving beer. Look at this gal. She seems to say, “I live to serve (men)!” And goats, I guess.

1880s poster for Bock Beer, courtesy of the Library of Congress.

A NEW WORLD?

But what about outside of Europe? Over in what we call the Americas, indigenous tribes were making a corn-based beer called chicha from way back, again, mostly brewed by women. They’d chew starchy things like maize and yucca, then spit them out and let them ferment in a bowl. Yummy. Apache women made a corn beer, known as tulpi or tulapa, that featured in girls' puberty rites.

But then foreigners came on over and crashed the party. Pilgrims brought their fear of drinking straight water and their love of low-alcohol “small beer” over with them to America. Legend has it that the Mayflower, which sailed over in 1620, stopped at Plymouth Rock not because that was their final destination, but because the captain was worried that they were running out of beer and they wouldn’t have enough for the sail home. When abroad, beer was crucial to survival.

Building breweries – and recruiting brewers – was top priority in colonies like Jamestown in my home state of Virginia. But in the early years, supplies were scarce, so they had to improvise with corn, pumpkin, spruce tips, birch sap, probably with some help from native peoples. Same goes for Australia.

But beer could be dangerous if you didn’t make it right. As one Jamestown colonist grumbled about a particularly sloppy brewer, “I would you could hang that villain Duppe who by his stinking beer hath poisoned…the colony.” Good thing there were plenty of female brewers making small beer at home. Everyone drank it: kids, pregnant women, old ladies. It wasn’t hopped, so it couldn’t travel far, making brewing a local enterprise. Thomas Jefferson and George Washington, those founding fathers whose faces still grace America’s dollar bills, both had alehouses: and their wives were very involved in the brewing process. In the early years of their marriage, Martha Jefferson brewed some 15-gallon batches of small beer every two weeks . She was quite well known for her wheat beer. Get it, Martha!

Brewsters brewed at home and in local taverns, where they could offer travelers and locals a tasty pint and a place to talk about, say, breaking away from Mother England. But beer was starting to go professional. And women were not encouraged to apply. In Philly, a woman named Mary Lisle became the colony’s first brewer in 1734 when she inherited her father’s brewery. But women were losing their stake in the game, giving us what has remained a very male-dominated business.

MODERN-DAY HOME BREW

Of course, in many places, women have never stopped brewing. In some African countries, homebrew continues to be a staple, made at home from recipes passed down from mother to daughter. Take umqombothi, made in South Africa: this low-alcohol, everyday beer for weddings, rituals, and meetings is usually made from maize and sorghum. Zulu tradition says that women should try all home brew first, just to make sure it’s safe before passing it on to their menfolk. Or, as I like to imagine it, to make sure they get the freshest taste. They sell any surplus by the pail, providing a source of income. Then there’s mbege, made by women in Tanzania from fermented bananas, which they sip through a straw. In Nepal, women spend a whole month brewing raksi, a pungent little drink made from rice.

And as Flora says, sometimes restriction is the mother of invention: “There are also a lot of countries that brew alcohol at home because alcohol consumption is forbidden, and they’ll just use sugar and baker’s yeast and make alcohol.”

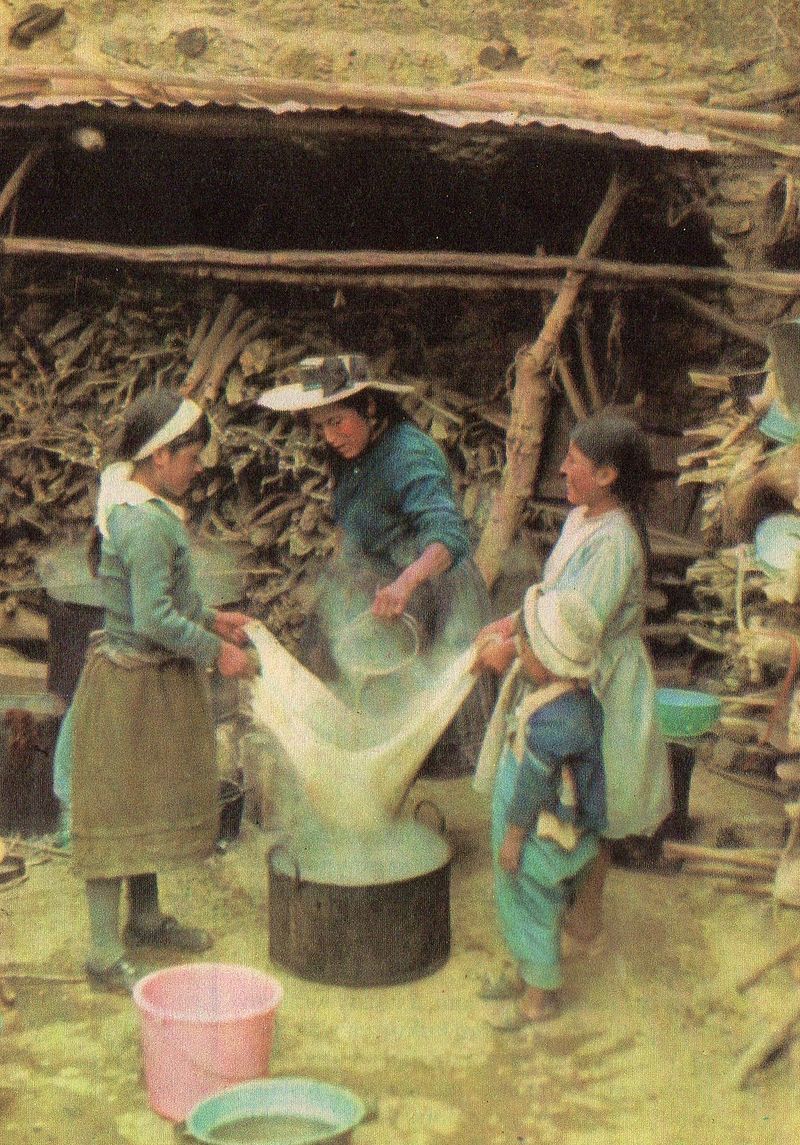

Women brewing chichi in Huacho sin Pescado (1980). It’s a lady-filled affair.

Image by Teresa Walendziak i Marek Doktor, from Wikicommons.

In all of these places, brewing provides a vital income for women, and they’re central to the process. But when it comes to women in commercial, big-time brewing, they’re still vastly outnumbered by men. In a 2014 Stanford poll, only 4% of American brewmasters were women. In the same year, Auburn University said that 29% of American brewery workers were women and 17% of breweries had female CEOs. Out of those, how many were solo female CEOs? Just 3%.

Maybe it’s that men LIKE beer more than women. If you went on TV ads alone, you’d almost think that women are allergic to the stuff, but we know that the ladies are drinking plenty. The rise in craft beer seems to be helping. A 2018 Nielsen Harris Poll suggested that Americans drinking craft beer on the regular were 31% female and 68% male – a definite rise on the women’s side.

The poll suggests out of some 14.7 million new craft beer drinkers since 2015, 6.6 million – a bit less than half – are women. Another recent poll suggests that women aged 18 to 34 are reaching for craft beer over white wine as their beverage of choice.

But in a video experiment shot by Anheuser Busch as part of their #WeAllLoveBeer campaign suggests that we still think of beer as a “man’s drink.” In it, hidden cameras showed several couples ordering drinks together. The woman orders a beer, while their male companions order something considered traditionally ‘girly’: a rose, a Cosmo. And yet, almost without fail, the waiter who brings their drinks out puts the beer in front of the guy. Because sparkling wine just can’t be for that burly gentleman, and this beer…well, my dear, it’s not for you.

But why, when we’ve been drinking it for most of our history? I have a little theory, and it crystalizes in the Victorian era. Remember those two very different spheres: the private, where women lived, and the public, where men worked? When beer moved out of the kitchen and into bars and taverns, it became firmly rooted in the public sphere: one that women, as a rule, weren’t welcome in. Well-to-do women in places like Australia, the UK, and America weren’t to be seen in pubs: it was seen as low-class, associated with rough women and ladies of the evening. Though women sometimes worked in these places as barmaids, they weren’t places for women to hang out as customers. As an Australian member of parliament reportedly said about women in bars, long after the Victorian era had finished: “the prestige of womanhood is too high and too valuable and too precious to be destroyed by a vulgarism.” And so “good” women didn’t tend to drink beer.

I asked Flora why she thought beer was perceived as a man’s beverage. “I think it’s because we have this association in mind that beer is something you drink with your mates. I guess it has been more social, more than something that’s related to gastronomy…people see wine as something you need to appreciate, whereas beer, you don’t really need opt appreciate the taste. You’ll drink it because it’s Saturday and you’re out with your mate.”

And in the days of yore, being out at a bar with your mate was a male-dominated pastime. In the 1800s and early 1900s, there were laws in many places that barred women from working OR drinking in saloons. In 1884, Australia’s Adelaide Advertiser reported on “the fearful injury wrought young men, by the seductive influence of young and exquisitely dressed barmaids in the saloons and back bars of several Adelaide hotels.” Because, of course, a woman in a bar must be a mercenary prostitute. I’m sure Gilgamesh would agree with you, Sir.

This isn’t just about a woman’s right to party. These are places where deals were struck and ideas were formed—where changed happened, and women weren’t allowed to take part. Things started changing in the Roaring ‘20s, when women started really hitting the town, and during WWII as they entered the workforce in big numbers. But in many places, women still weren’t welcome in bars.

In Australia and New Zealand, women had separate ladies’ lounges and weren’t allowed to come into the men’s bar at all. In 1965, in the balmy city of Brisbane, Merle Thornton and Rosalie Bognor chained themselves to the bar at the Regatta Hotel. They’d gone to see the governor the day before and been laughed at, so they decided to march on in and make a point. The bartender refused to serve them, but some male patrons bought them drinks in solidarity while policemen found some tools to cut through their chains.This act of protest against being barred from the bar resulted in death threats and mean comments about how these women were neglecting their children. They paved the way for women to drink in public bars, but it wasn’t made legal in Queensland until 1970. The Regatta’s bar in now called Merle’s.

Barred from the bar? Let’s break out our handcuffs.

Merle Thornton and Rosalie Bognor at the Regatta Hotel, as captured by Brisbane’s Courier Mail.

Here’s the thing: some women don’t like beer. You do you. But such attitudes about women and drinking, particularly their drinking beer, has played a part. Take a look at beer advertising. Historically it either objectifies women, or just leaves them out entirely. Go ahead and Google any major beer ad campaign and try to find one that’s woman-focused. You’ll find plenty of women serving beer to male customers, most likely flashing a whole lot of cleavage. And then there are ads like Bud Light’s “Up For Whatever” campaign, when they plastered their cans with the tag line “The perfect beer for removing ‘no’ from your vocabulary for the night.” OOOOOH my yikes.

How do I even capture this….for more such gems from the past, check out this slideshow. Or just Google ‘sexist beer ads’ and get ready to rage.

A 2018 study done in the UK, called The Gender Pint Gap, says that male-oriented adverts keep some 27% of women from drinking beer: for younger female drinkers between 18 and 24, that number rises to 48%. There’s also beer’s high calorie count, AKA fear of the “beer belly” (and yes, beer does tend to have a decent number of calories, but it’s better for you in terms of vitamins, minerals, and good bacteria than wine. At least that’s what I tell myself when I drink that 7% IPA) And then there’s the 17% of women who said they feared being judged for drinking beer. Judged for drinking something that, somewhere along the line, they learned was “not for them.”

But look behind brewpub counters, into home brew sheds, and between the giant tanks at breweries, and you’ll find more and more women coming back to the fold. I asked Flora how she came to love beer and brewing. “I think I got into beer first, just because I ended up trying a few that I liked and coming back to it, and being keen to try more variety and learn about it. And brewing came a few years later, because I studied biotech engineering. I was working on making alcohol as fuel, and the process is obviously very similar to making alcohol for human consumption. So it became quite obvious that I could use my tech skills for something a bit more fun…a few years ago I got seriously into brewing, and then why not brewing as a career?”

Flora and I hanging out by Colonial Brewing Co.’s giant tanks. To find out more about this delightful brewery, check out their website.

Image taken by Paul Gablonski

Flora feels like, of all the male-dominated professions she’s worked in, brewing has been the easiest to break into. “I feel that in the beer industry there’s a lot of young people, and they probably have a bit less preconception about a female working in their field. I think for a male-dominated industry, beer is an easy one to get in. It could be much harder.”

But that doesn’t stop people from being surprised when she says she’s a professional brewer. “Most of the time, I just get ‘oh, that’s really cool,’ and then they’ll ask me my favorite type of beer. But yeah, there’ll be a few people who don’t really get it, and they’ll ask if I’m in marketing at the brewery, until I physically have to describe ‘well the malt, and turn it into beer.’ But I think most people are getting used to there being female brewers out there.”

And there are barriers to women being brewers: much like women who want to join the armed forces, something as seemingly simple as weightlifting can play a big part in keeping the ladies out of a competitive field. “There will still be people advertising for a role, and it says you need to do heavy lifting, and that doesn’t make you feel very welcome.” Imagine if the only thing between you and your dream job as a professional brewer was your ability to lift a 25 kilo bag of grain. Does this sound like a G.I. Jane-type situation?

Luckily there are organizations like Pink Boots, which supports female brewers in the field. They’re currently working on getting malt suppliers to move from 25 kilo bags to 12 kilo bags, a change that Flora said would change many female brewer’s lives.

“Pink Boots is really great. Having worked in a male-dominated field for my whole career, I feel it’s the first time that being a woman comes with an advantage…It makes us much stronger because we have support. It also makes us more visible, and that means it’s more normal to be a female in this industry.”

There’s something nice to me about the idea of women coming home to brewing: finding it again, both the craft of brewing it and the enjoyment to be had in drinking it.

So let’s raise a glass to female brewers: of the ancient past, the present, and future.

Cheers!

And that wraps up our ancient Egypt chapter.

I’ll be back in a handful of weeks with a whole new empire to explore, and a whole host of fascinating women. Until next time.

Flora and I recording in front of Colonial Brewing in Melbourne, Australia.

Image taken by Paul Gablonski.

voices

John Armstrong

Paul Gablonski

Simon Dinatris

Music

“Pippin the Hunchback” from the album Thatched Villagers by Kevin Macleod

“Many Roads, Many Travels,” “Festival Dance,” And “Journey Down the Nile” from the album Children of the Nile by Keith Zizza.

All other music lisenced from Audioblocks.com.