It’s All Greek to Me: A Lady’s Life in Ancient Greece

Ancient Greece is the bedrock of western civilization.

It handed us art, architecture, philosophy, and political ideals that are still very much in play today. It’s where we got the idea that everyone should have a say in their government: well, unless you’re a foreigner, a slave…or a woman. There’s a lot to admire about ancient Greek culture, but their respect for a lady’s autonomy is not one of them. It has a reputation for putting women down, trapping them in the house and chaining them to the loom. But was life for women in cities like Athens really so restrictive? Let’s peek behind the curtains of a Greek woman’s day to find out what filled her hours. Let’s see how they managed to work the system, charming their way into senator’s ears and influencing them from behind their veils and curtains. Because no law can keep an enterprising woman down.

Grab your sandals, a bedsheet, and a few shiny bangles. Let’s go traveling.

MY SOURCES

books

Ancient Greece: Everyday Life in the Birthplace of Western Civilization. Robert Garland, Sterling, 2013.

The Amazons: Lives and Legends of Warrior Women Across the Ancient World. Adrienne Mayor, Princeton University Press, 2014.

Women Warriors: An Unexpected History. Pamela Toler, Beacon Press, 201p.

Encyclopedia of Hair: A Cultural History. Victoria Sherrow, Greenwood, Feb. 2006.

Plutarch's Life of Lycurgus, chap. xviii (51B).

AUDIO

The History of Ancient Greece podcast by Ryan Stitt. If you’re looking to go deep diving into ancient Greece in more depth, this is where to go!

ONLINE

“Delphic Oracle's Lips May Have Been Loosened by Gas Vapors.” National Geographic, 2001.

“Wine, Women, and Wisdom: The Symposia of Ancient Greece.” By Francisco Javior Murcia, National Geographic HISTORY Magazine, Feb. 2017.

“Hetaira.” Encyclopaedia Romana, accessed June 2019.

“Researchers Uncover Ancient Greek Island’s Complex Plumbing System.” By Jason Daley, Smithsonian.com, Jan. 2018.

“The Secret History of Ancient Toilets.” By Chelsea Wald, Nature.com, May 2016.

“Phryne, The Ancient Greek Prostitute Who Flashed Her Way to Freedom.” By Theodoros Karasavvas, Ancient Origins, Feb. 2017.

“Hairstyles in the Arts of Greek and Roman Antiquity.” By Norbert Haas, FrancoiseToppe, Beate M.Henz. Journal of Investigative Dermatology Symposium Proceedings.

Volume 10, Issue 3, December 2005, Pages 298-300.

“House and veil in ancient Greece.” By Lloyd Llewellyn-Jones, British School at Athens Studies. Vol. 15, BUILDING COMMUNITIES: House, Settlement and Society in the Aegean and Beyond (2007), pp. 251-258.

“Keepers of the Faith.” By Steve Coates, New York Times (Sunday Book Review), July 20o7.

“Cynisca and the Heraean Games: The Female Athletes of Ancient Greece.” By Shirsho Dasgupta, The Wire, Aug. 2016.

“The Greek Festival of Thesmophoria.” By N.S. Gill, Thoughtco, May 2019.

“Death, Burial, and the Afterlife in Ancient Greece.” Department of Greek and Roman Art. In Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Oct. 2003.

let’s go traveling!

Terracotta column-krater (a bowl for mixing wine and water) showing Jason and his hunt for the Golden Fleece. Courtesy of the MET.

episode TRANSCRIPT

Part 1

I chop and change a bit as I record, so this won’t be exact. Please forgive any spelling or formatting weirdness. any quotes highlighted in bold are not actual historical quotes: just me having fun with fiction.

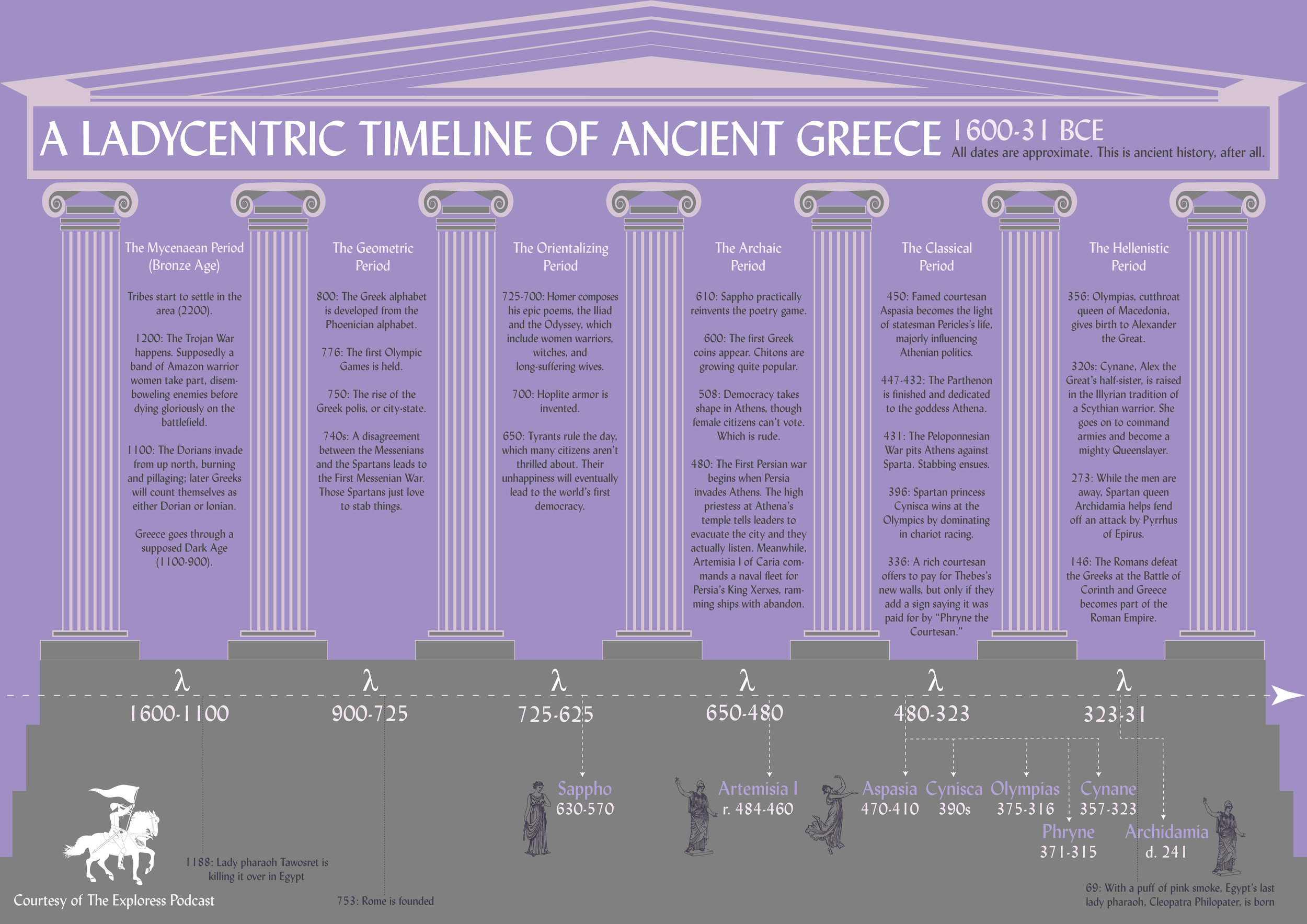

When we talk about ancient history, it’s hard to say exactly when a civilization rose and fell. It’s hard to sum up what life is like for a lady when we’re talking about a civilization that’s hopping for more than 1,000 years. So let’s start here: what counts as “ancient Greece”? It starts around 1600 BCE with the Myceneans and what’s called the Bronze Age. Think epic myths and vengeful gods, burly heroes and the Trojan War. This is a time when Greece is a collection of tribes, often warring against each other. They rule from places like Mycenae (the traditional home of that ass hat Agamemnon), Tiryns, Thebes, Argos, and Troy. As that age falls away around 1100, we eventually see the rise of city-states like Athens; the Greek alphabet crops up around 800 BCE, and the first Olympic Games are held in 776. In the 7th and 6th centuries, you’ve got tyrants lording it over much of Greece, until eventually the people grow so tired of rich men’s power games and say, “you know what? It’s democracy time.” After fighting some harrowing wars with the Persians, we enter what’s called the Classical Period, which runs from 480 to around 323. It’s something of a Golden Age for Greece: radical democracy is popping off, the wine is flowing, and the arts are blossoming, giving birth to great buildings like the Parthenon. In 321 you have the start of the Hellenistic Period, which is where we’ll find Alexander the Great and his hardcore lady relations, all the way up until Rome takes things over in 31.

This timeline really comes alive when you see it blown up to full size. If you like it, check it out on my Etsy shop: just go to my Merchandise page.

If this timeline feels less like a straight, ordered line in your head and more like a tangled mess of necklaces in your junk drawer, you’re in luck. I’ve made a nifty lady-centric timeline of ancient Greece for you! Wander over to my website and this episode’s show notes, and pull it up in all its pretty infographic glory. While you’re there, check out the map of ancient Greece and its surroundings I made you, which will help make sense of where the action’s happening.

I’ve left some places out so I could focus on the women and places we’ll touch on in our episodes on ancient Greece. This map really comes alive when you see it blown up to full size. If you like it, check it out on my Etsy shop: just go to my Merchandise page.

So let’s time travel back to the Classical Period, around 432, as well-to-do daughters in the city of Athens. Stretch your arms, ladies: it’s time to start our day. And it’s a special one, because today, you’re getting married. To Tom Hiddleston, obviously. Because…who else?

But first, let’s enjoy our last morning in our father’s house. The most basic unit of Greek society is the household, or oikos. In ancient Greece, the family always comes first. Beyond that, our social structure goes as follows: there’s a genos, or larger clan group descended from the same ancestor, who may or may not be a god. Then there’s the phratry, which means “brotherhood.” You have to belong to one in order to be an Athenian citizen. Membership within your polis, in this case the city-state of Athens, is a more exclusive club than you’d think. If you’re a metic—a resident alien—you hover somewhere between being a foreigner and a citizen.You have rights, but you’re never going to be a full citizen. And that goes for your children too.

Then there’s your deme, or local district, kind of like your local voting district. And last, your tribe. Greeks think of themselves as descended from either the Dorians or the Ionians, which underpins certain rivalries and is the basis of our civil administration system.

But back to family. The house is likely to be pretty crowded, as an extended family network lives here. Our father is the head of it – the one who makes all the major decisions and controls all of the assets. Yes, including you! Then there’s our mother, who’s in charge of running the home. Other family members live with us: grandparents, perhaps our brother and his wife, and, of course, our household slaves. It’s a sad reality of our current situation that we’re going to run into slaves quite often.

You look out the window. Your city has some truly impressive public buildings on the Acropolis: the high, level hill full of beautiful temples and shrines gleaming with the tall columns and fine statues we time travelers most associate with ancient Greece. The Parthenon, which has just been finished, sits up there looking grand and stately. It holds Athena Parthenos, a 36-foot-tall gold and ivory sculpture of the goddess Athena, patron saint of the city and all-around badass.

But our house isn’t likely to be all that fancy. They tend to have a central, open courtyard surrounded on all four sides by other rooms. We may be in a ladies-only part of our house, tucked away from prying male eyes, but that probably depends on the household. We may even sleep on a second floor. But the materials within aren’t fancy: this isn’t the Parthenon, after all. The floors are likely to be beaten earth, clay or paving stones. Wooden furniture’s expensive, so there won’t be much of it; perhaps some animal skin rugs and some very small windows, no glass, with shutters you can close if the sun gets too bitey. The walls are made of mud brick, perhaps coated in lime to make them look a bit nicer. But they’re thin and not very well made. Remember that hole you punched in the wall of your cheap college rental apartment when you swung a door open too hard? This is worse. One time a robber broke into your house by busting a hole through one of your walls. That’s why the most common word for a thief in this era is “wall digger.”

PREPPING FOR THE DAY

It’s still dark, so we’ll need to light our oil lamp, made by sticking a wick into olive oil. If you find yourself in need of a bathroom break, search out the boat-shaped chamber pot that’s bound to be floating around somewhere. It’s not guaranteed we’ll have indoor plumbing, though we know such technology is already around. The Minoans built Europe’s first drainage system and flushing toilets at the Palace of Knossos on the island of Crete: for fancy ladies only. In ancient Greece, you know you’ve made it when you have the ability to flush. By the Classical Period and the Hellenistic period that’ll come after it, we’ve got public latrines —basically big rooms with bench seats featuring a bunch of holes in them and a drainage system running underneath to sweep your refuse away. Apparently politicians and philosophers spend a lot of time chatting here. The guys who poop together…think together? But we’re at home, not in a public bathhouse, so…it’s the chamber pot or nothing.

this bronze mirror has seen better days, but it’s still pretty fancy.

Mid-fifth century BCE, courtesy of the MET.

Since we have a bit of money, we might indulge in a soak in our terra-cotta bathtub. One of your slaves will need to cart and heat that water by hand, so this is not something you’re doing every morning. Some families will have a well in their yard, but most have to make their way to the communal water fountain. It’s a great place to stand around and gossip, but you may have to wait in line for your bucketful.

Given how labor intensive the whole operation is, you’re unlikely to actually immerse yourself in water. And you won’t be using soap: that’s just for the laundry. Instead you’ll coat your body in olive oil, then scrape it off with a strigil. Olive oil: is there anything it can’t do? We’ll also need to make sure to remove any uncouth body hair, which means anything in the pubic area. The ancient Greeks are not down with a lady jungle, so we’ll remove it either by singeing and/or plucking.

Now that we’re clean, you’ll want to dab on some perfume. It’s popular with both men and women, and is usually made by boiling flower petals to extract their essence. Make sure to bring a little with you when you go out into the city later, because Athens most certainly does NOT smell like roses.

Now, we get dressed. You might start by binding your breasts in an ancient bra called a strophion, which is really just a simple cloth band arrangement. Not a very supportive contraption, but it’s not like you’re going to be going to the gym. It’s unlikely you’ll be wearing any underwear, though your outfit will leave you exposed to any passing breeze: in the ancient world, this seems to be a trend. I hope you brought some with you, or you’ll be going commando.

Fashion here is fairly utilitarian: we are not glamming it up quite like those fashion icons the Egyptians. A guy named Alkibiades causes a huge sensation just for going about wearing a purple robe in public: so that’ll give you an idea of what counts as scandalous in terms of dress code.

Most garments are made of wool, though there is some linen, woven by women at home. Lucky for you, Greek dress isn’t hard to master: it’s essentially an artfully folded bedsheet. It’s not the garment that counts, really: it’s how you wear it. In earlier eras, we would have worn something called a peplos: picture holding up a wool blanket, then folding one of the short ends over about a third of the way. You’ll wrap it around you, holding that doubled-over section over your breasts and midsection and running it under your armpits. Then you’ll pin it at both shoulders and belt it, creating a sleeveless, floor-length gown. This style is worn by both men and women, but apparently such fashion can be dangerous. Herodotus tells us that, when a mob decided to attack a guy they didn’t approve of, they whipped off their giant dress pins and stabbed him to death like a giant, fleshy pincushion.

Now we’re probably rocking a chiton. Picture a giant sack with arms: that’s our starting point. You’ll belt it and pin up the sleeves in several places, creating a drapey elbow-length thing that has got to be one of the easiest outfits ever for a time traveler to wear without incident. Be careful, though, as one side probably isn’t sewn closed and you’re likely to flash someone if you walk too fast.

While Doric chitons are usually woolen, Ionic ones are made of linen or even silk, which will hug the body a little more closely and feel more luxurious…and definitely less itchy. The styles are sometimes even worn overlapped for something a little extra. Regardless, unless you’re a lady of the evening you should make sure no one can see too much of you through all those artful folds. Male nudity is not at all a big deal here, but your lady bits are a different story.

Now, for beautifying. We Greeks are big on the whole “I woke up like this” look, but that doesn’t mean we aren’t applying any makeup. Just that it shouldn't LOOK like we’ve used any. Pale skin is very in, as it shows how little time we spend outside working: staying inside all day. Winning! That’s why we carry umbrellas called skaidon in public just to keep the sun off our skin. But we might add a little powder to our faces to emphasize our paleness. Be warned: our white face paint is made out of lead that’s been soaked in vinegar, which was then heated and made into a powder. Lead: not great for the pores…or your vital organs. We might apply little circles of rouge made with mulberries and seaweed to our cheeks, and grease our lips with oil or wax. The other thing we’ll want to pay special attention to is our eyebrows. While we have plucking tools at our disposal – tweezers, for one – we won’t be using them to tame our brows. Oh, no! Because it turns out the ancient Greeks enjoy…well, not quite a solid unibrow, but one that’s loosely connected and caterpillar full. Frida Kahlo would have fit right in here. Break out the soot or antimony, because we will darken them and our eyelashes before claiming ourselves ready to party. We may even slap on some fake eyebrows made of dyed goat hair and adhered with resin. That’ll for sure make a statement!

Your hair is likely to be long: only slaves keep theirs short – you wouldn’t want to be confused with one of them, would you? – and women in mourning. Because we’re getting married, we’ll be sweeping it back. We might curl it with an iron, tucking it up in a low bun, and decorate it with shiny pins, a headband, or a diadem. So far, not bad!

When we’re hanging out at home, we’re likely to go barefoot. But later, when we’re heading out, we’ll wear sandals. We’re likely to have on some earrings and a necklace made of terra cotta, or copper, or lead, or even silver and gold. But we don’t want to be too showy: a good Greek woman does not demand attention. Better that she blend into the walls as much as possible, or so the ancient Greek writers like to say. Because we’re getting married and becoming matrons, we will be covering our hair and wearing a veil from now on when we go out in public.

Veiling are fairly common in the ancient world. It’s something women in our century still do, which tends to get a bit caught up in controversy. We can see this veiling practice in one of two ways: one, as a means of hiding a woman away and forcing her into submission. The word for veil, kredemnon, translates to “city walls” or “battlements” – a defensive strategy that not only separates her from the public sphere, but marks her as a taken woman: someone else’s property, so please don’t touch. Women who go about uncovered are considered lesser than, wanton: likely to be ladies of the evening or slaves. But on the other hand, the veil makes her next to invisible, which can also give us some freedom of both movement and expression. Our veils let us be in public while still maintaining our privacy. Perhaps there’s something to be said about that.

A WOMAN’S PLACE

Let’s head downstairs. We divide our day into 12-hour blocks, night and day, but we have no system for breaking up the hours. There are no clocks, so if you’re wondering how long you’ve got to wait ‘til wedding time, you’re going to have to check your sundial. There is one nifty way to tell the time, used in law courts, called a klepsydra, or water clock. It consists of a clay vessel full of water with a plugged hole in its bottom. When a speaker is ready, it’s unplugged and he’s allowed to talk until the water runs out. That water will run for exactly six minutes, which means everyone is guaranteed the same amount of talking time. I’m sure plenty of ancient Greek housewives wish they could make their husbands abide by them at home.

We’re unlikely to have much of a breakfast. We’re eating two meals a day: ariston, a light lunch, and deipnon, or dinner, which is our biggest meal of the day. Instead let’s wander about the house, reminiscing and seeing what the other ladies of the house are up to. Your mother and sisters may not get out much, but this house is her domain: she runs the slaves and all the children. Though it’s the man of the house who serves as its main priest.

GIRL, PREACH

We have to stop here and consider the gods for a minute, because they are everywhere in ancient Greece. There are 12 main Olympian gods, split fairly evenly between men and women.

And though they look human and have human emotions, their powers are heady and terrifying. Their presence is felt in everything: the home, the crops, the streets, and they can change your fate. Though their attention has to be attracted first: they’re busy with their own affairs and aren’t all that interested in yours, unless you catch their notice. At your home altar you’re likely to say a prayer, and perhaps make an offering or a sacrifice to the god you want the favor of. It might be in the form of food and drink, but it also might be animal blood. I hope you don’t mind slitting goat’s throats, because that’s likely to feature at some point in your day. The gods don’t give something for nothing, so you do what you can to appease them. Arrogant, fickle, cruel, and jealous, our gods are not afraid to punish. If you don’t mind them, things could go downhill for you fast.

There are many very powerful goddesses, who I’ll be talking about more in upcoming bonus episodes over on Patreon. Athena, the virgin goddess of wisdom, warfare, and handicrafts, who wears a serious helmet and will spear you where you stand. And then there’s Artemis: goddess of the hunt and of the wilderness, and the protector of girls. Any god who tries to rape her tends to meet a very violent end. Boys, bye! And yet unlike in ancient Egypt, that power and potency doesn’t seem to trickle down into the human realm. Well, unless you’re talking about an ancient Greek priestess.

Here’s a truth we’ll run into throughout the ancient world: religion gives women a path to power, influence, and independence that few of the women around them can claim. Women can join religious cults as dedicated priestesses. And unlike in some ancient civilizations, you don’t need to be a virgin to do it: some are also wives and mothers. Yass, priestess! You have that cake and eat it too.

For their sacrifice, these women are often paid, awarded public statues and lavish funerals, given property, and most crucially, a heaping pile of respect for their wisdom on matters of state and religion.

They’re allowed to charge for their services, giving them an income stream; they can argue in court; they’re celebrities where they live, and get all the privileges that tends to afford. And because religion and politics are so tightly linked here, our role as priestess gives us sway over what’s happening around us. In Athens, the high priestess of Athena Polias is one of the most influential women in the city: when she speaks, men listen. In 480, before the battle of Salamis against the mighty Persians, the high priestess told the leaders that they should evacuate because Athena’s sacred snake didn’t eat its honey cake. And they did it right quick, because that snake don’t lie.

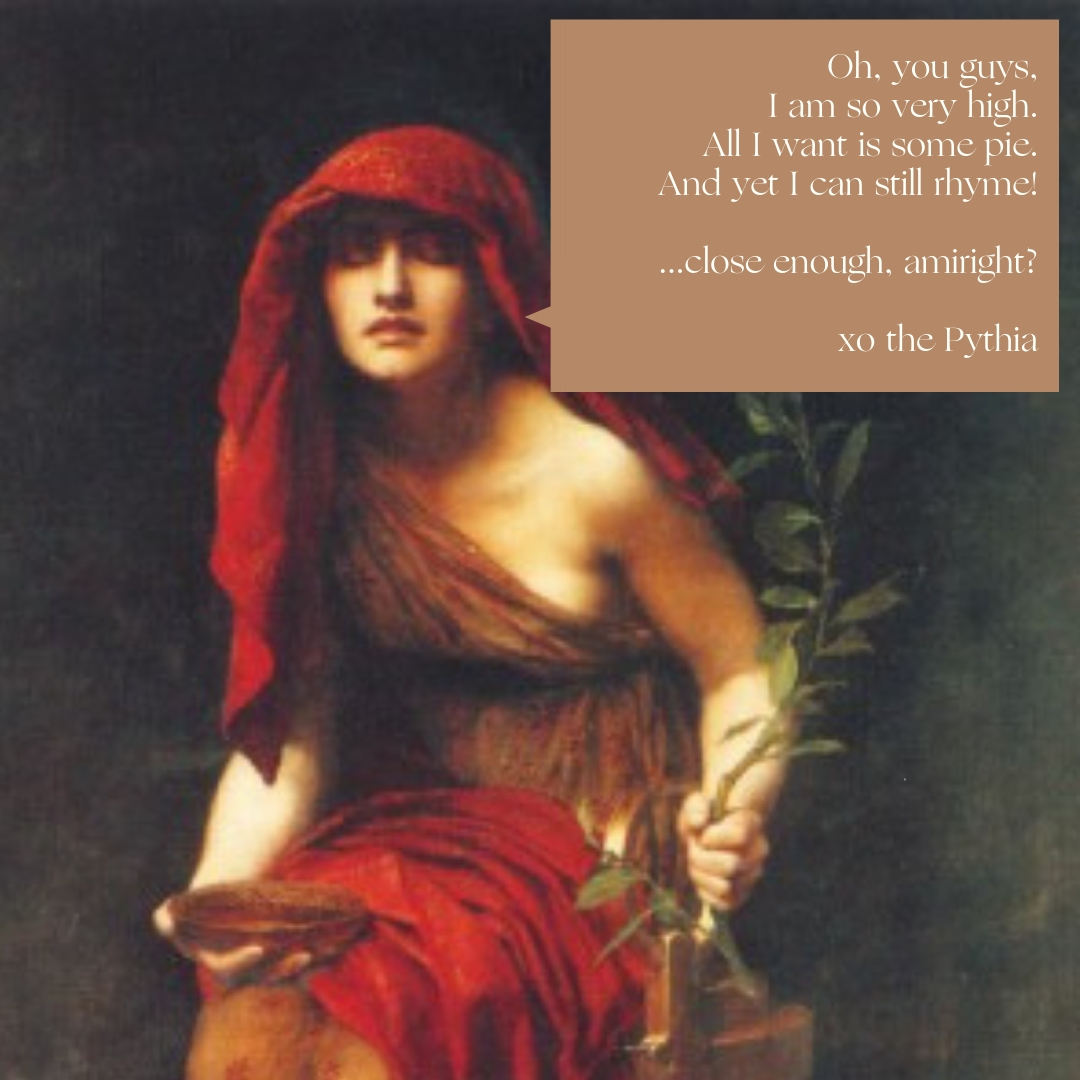

Important men come from all over Greece to consult the Oracle at Delphi, who resides at the temple of Apollo on Mount Parnassus at what the Greeks consider the very center of the world. The oracle, called the Pythia, sits on high as men ask her to be their risk consultant. The fates of whole peoples often rest on her answer. The priestess falls into a dream-like trance – probably, modern-day researchers think, because of the ethylene gases that rise from cracks in the rock there – gets high as a kite, and hands out predictions in hexameter verse. You have to be celibate for life in this office, but at least you get to have some hallucinogenic fun.

Priestess of Delphi by John Collier

But let’s get back to our housebound wanderings. There is no Netflix or Candy Krush to pass the time, especially for housebound girls. You’re probably pretty busy helping out around the house, anyway. When you were younger, you might have gotten out your knucklebones to entertain yourself, trying to catch them on the back of your hand. Or you might have played some kind of ball game with siblings. Though the balls are DIY and involve blowing up a pig’s bladder and heating it in the ashes of your fire. So, good luck with that.

Now that you’re a little older, you’re bound to spend some time behind the loom. There are no department stores in this era: everything is made by hand. Most clothes are made at home by women, and spinning can help supplement the family’s income. This is not a quick little morning project. The wool has to be cleaned, then scoured to get rid of all the burrs and dung and whatever else your sheep have gotten up in there. Then you’ve got to comb it with a semicircular brush called a epinitron, fitted snug over your thigh. If you’ve ever tried to untangle a huge ball of yarn, picture that, except it smells real funny. Then you’ll dye it in a vat, let it dry, and wind it up onto a spindle.

You’d better get used to sitting behind a huge loom, because you’ll do it very often. In Homer’s Odyssey, an ingenious woman named Penelope uses hers to cunning advantage. With her husband Odysseus missing, she tells the wide range of suitors pressuring her to remarry that she’ll pick one of them just a soon as she finishes weaving the tapestry she’s making. She works on it by day, then unpicks it at night. Who says a woman’s work can’t be ingenious?

Your father probably isn’t home: he has important things to do, like participate in the world’s first radical democracy. After kicking out a few tyrants who tried to run things, we’ve taken on a totally different approach to civil leadership. There are almost no elections: this is a direct democracy, where most offices are filled by random lottery. Any of the city’s 30,000 eligible citizens can attend the ecclesia, a general meeting, a couple times a month: in fact, it’s considered a duty. It’s a place where anyone can talk, propose a law, or make a lawsuit.

The Acropolis of Athens by Leo von Klenze (1846).

As such, he’ll be out and about, striking deals and talking to people. He’s bound to find his way to the Agora: a combination lecture hall, market, administration building, court of law, and general meeting place. This place lives at the beating heart of Greek life. Picture a long, rectangular building with a sloped roof and many columns lining each side of the building, letting people wander in and out between them. It’s a bustling place to see and be seen.

Dear old dad might be signing contracts, because he’s a well-to-do man who’s gotten a good education. But it’s hard to say if you grew up learning to read and write yourself. Some estimates suggest that only around 30% of the city’s population can. Very few of those, it seems, are women. As a stabworthy character named Menander says in a play now lost to us: “He who teaches his wife how to read and write does no good. He’s giving additional poison to a horrible snake.” Mmk, Menander. Why don’t you just go and choke on a hambone.

But given how infrequently our Greek writers deign to mention women, who knows how many are participating in public life. A vase dated around 440 BCE shows a woman seated and reading a scroll; some people think it’s Sappho, that great ancient Poetess. But we’ll return to that saucy minx a little later.

He’ll be writing on papyrus, which we call biblos: it's where the word Bible comes from. The Egyptians handed this plant-based paper down to us, and it’s very handy, but not cheap. So we might also use ostraka, or broken pieces of pottery, as it’s much less expensive. The Agora has rolls for sale, and documents are often copied out by slaves, who one hopes sneakily taught themselves to read while they’re at it.

Most pieces of literature are shared orally: the printing press is still a long way off. You’re likely to know the Iliad because you’ve heard someone recite it. These public slam poets are called, delightfully, rhapsodes, or “song stitchers.” How likely you are to be out in public to hear these gems is anyone’s guess.

What about your brother: where’s he? Probably pumping some iron over at the local gym. Men in Athens take physical fitness VERY seriously. Work is just an interruption; working out is a way of life. If you’ve ever looked at a Greek vase or painting, you’ll know that ripped abs, cut thighs, and startlingly little body hair are pretty much a prerequisite to Greekness. As Hans and Franz would say, we Greeks really want to “PUMP: you up!” Though of course, we have to be careful trying to guess what ancient Greeks look like based on artwork: if aliens came down and judged we modern-day humans solely on pictures of GQ models, they’d probably get the wrong idea.

Leonidas at Thermoplae by Jacques-Louis.

But despite the current state of his pecs, your brother’s bound to be at the gymnasium: the word comes from the Greek word gymnos, which means “naked.” Why is the gym literally called the “place of nakedness”? Because they’re all working out in their birthday suits! For real: these guys have a trainer who’s called the paidotribes, or “boy rubber,” because of how much oil he massages his charges with. Olympic athletes compete entirely greased up and in the nude. Nude discus throwing: now that’d be a sight to see. That’s one of the reasons we ladies aren’t allowed to go and watch the Olympics! Well, us married ladies: apparently unwed girls can go and ogle the greased-up athletes. The issue, it seems, is that married women aren’t supposed to see other men’s members. If we do, says Greek travel writer Pausanias, we’ll be “cast down from Mount Typaeum into the river flowing below.” Well that’s rude.

We will NOT be training in the gym, that’s for sure. We certainly won’t be participating in the Games as athletes. But we can participate in the sister Games, called The Heraean Games, dedicated to goddess Hera. You’re out of luck if your strength is synchronized swimming, though: the only competition we can enter is foot races, but hey, at least we’re here.

But there is one woman who’s keen to bust through the Olympics’ particularly greasy glass ceiling, and that’s a Spartan princess named Cynisca. In 396, she will become the first woman to win at the Olympics. You have to wonder what she thought of all those flying manly members: I can’t imagine they let her compete in the nude, but we can dream. Her four-horse chariot-racing prowess sees her beat her competition not just at one Games, but two of them: though of course she never gets to claim her olive wreath, as she has lady parts. Ugh, ancient misogyny. Women won’t officially compete in the Olympics until 1900 in Paris . You’ve got to hand it to Cynisca: she’s way ahead of her time.

INVISIBLE WOMEN?

So while our male relations are lifting weights, signing contracts, and taking long steams in the public baths—in the nude, of course. Are we getting out to participate in this lively public sphere? Not really. A woman’s place is most certainly NOT making speeches in public or running around in the buff drenched in oil. The Odyssey gives us this advice: “Go inside the house, and attend to your work, the loom and distaff, and bid your handmaidens attend to their work also. Talking is men’s business…” Yes, ladies: according to Greek lit, we should make ourselves as invisible as possible. Because, as the great orator Pericles puts it, “…greatest will be her glory who is least talked of among men, whether in praise or in criticism.” Interesting, coming from a guy who owes much of his fame to a very eloquent courtesan. But more on her in a bit.

Remember when I said that our democracy is for all ELIGIBLE citizens? Freeborn women, slaves, and all foreigners living in the city don’t count. And when you factor in those too young to participate, you’ve only got 10 to 20% of the populace making the big decisions in government. And those people are all men. Unless, of course, you count the female priestesses we talked about earlier: you tell them, oracle!

It’s only right, as you get ready to have your life transferred from your father’s authority to Tom Hiddleston’s, that you be thinking about your rights under the law. The sad fact is that Athenian women have very few of them. We can’t sell land, buy it, or pass it down to our children. Everything we own is by proxy of a male guardian of one form or another: even our dowries are controlled by the men in our lives. One fourth-century contract actually says that a woman can’t legally agree to any contract that’s worth more than a medimnos of barley: that’s enough to keep a family alive for a week, if they’re very frugal.

This system sounds repressive, to be sure: women bound to the house, told to be quiet and invisible. But is that how it really is in ancient Greece, or is that how the ancient writers want us to see it? So much of what we know about a lady’s life in this age comes from literature: stories and artwork that are all about capturing what the artist thinks the ideal woman SHOULD be. But we know that some women – priestesses, courtesans, wives – found ways of wielding power. And there are tales that offer alternate versions of the woman’s story. Most of the ladies who feature in the Odyssey, that story about Odysseus’ VERY long boat trip back to Ithaca, are strong-willed and powerful. There’s Calypso, who holds Odysseus captive on her island for seven years of sexy business. And Circe, who poisons his crew, turns them into pigs, and THEN holds him captive for sexy business. And there’s also his bomb wife Penelope who keeps hundreds of angry suitors at bay while her husband’s off sleeping with goddesses.

And then we have scenes like this one, from a poem by Theokritos written in the third century. In it, Lady 1 arrives at her friend Lady 2’s house later than expected, and Lady 1 complains about how far out the friend’s husband has moved them. Lady 2 replies: “It’s that stupid husband of mine. HE buys this house out in the wilds—it’s not even a house—it’s just a hovel—purely to stop us from seeing each other. He’s spiteful, just like all men.” When Lady 1 says she shouldn’t talk like that in front of her baby, as he’ll understand she’s trash-talking Daddy, Lady 2 says: “The other day I told that daddy of hers to pop out and get some soap and red dye and the idiot came back with a cube of salt!”

These are stories, myths, and poems: in truth, it’s difficult to know how much they reflect Greek women’s lived experience. But it’s hard to imagine that all Greek ladies are following the ancient ideal of the quiet, subservient woman. I suspect that being a woman doesn’t bar us from power and influence, if we know how to seize it. We just have to learn how to wield it from behind fans, under veils, and through dividers.

GOING TO THE CHAPEL

On that note, let’s get back to our betrothed. On our wedding day, we’re likely to be 14 or 15, and Tom is probably at least 30. I have a friend who goes by the half-your-age-then-add-seven rule for dating: if a suitor falls under that bar, he’s too young. The Greeks, by contract, seem to stop their rule at “half your age.” At LEAST.

You’ve been prepared for this. From ages five until puberty, this is the moment you’ve known you were heading for. You may even have been chosen to serve the goddess Artemis in her sanctuary. Artemis is an important figure in our lives: as one of the heavens’ most virulent virgins, she looks down on everything having to do with sex and childbirth. Whenever a woman does something that involves her lady palace – gets married, gives birth – she has to make offerings to Artemis to try and appease her. As a young girl at her sanctuary at Brauron, you would have put on yellow robes and acted the part of the “little bear,” running around like an untamed animal. Then you put your doll on the altar, marking our movement from childhood to adulthood, implying that we wild things are ready to be tamed.

We happen to love Tom, which is unusual. Even if you didn’t, you’d have to marry him anyway. Marriage, particularly between the upper classes, serves as a means of collecting wealth and cementing good family connections. You are one of your father’s greatest bargaining chips. For most women, it isn’t optional, and it is most certainly not about you following your bliss. If your family can afford it, you’ll get married with a dowry: a sum of money meant to pay for your maintenance in your new husband’s house. It’s protection, too, in case you end up divorcing him: in that case, he’ll have to give your dowry right back to dear old dad. Some women – ones whose father dies, leaving no male heir to take things over – are in a unique position. They don’t own their father’s property as such, but it does go with them when they marry. And so they often end up tying the knot with their uncles to keep the house and lands in the family. Thank the gods we’re not doing that.

We’re getting married smack in the middle of Gamelion, the winter month which is high wedding season in Athens. The day will start with a sacrifice to Zeus and Hera, the gods of marriage. Which is darkly funny, seeing as Zeus is fond of sexually assaulting any mortal woman he happens to find pleasing. And he’s creative about it, terrorizing women in a variety of guises: as a bull, as a swan. He even impregnates a woman by turning himself into a golden shower. Ugh. Really?

We will also dedicate some of our old toys to Artemis to try and soothe her hurt feelings about losing our V card. Then we’ll get to a ritual cleansing. Water is poured over us – not a golden shower, thank the goddess – from a vase called a loutrophoros. This is supposed to help get us prepped for our new life. Then we’ll go to a feast, which our father will hold.

Let’s talk about food, as I’m sure you’re getting hungry. As far as ancient diets go, this one ain’t that bad. Picture what we call a Mediterranean Diet: that’s more or less what we’re dealing with. Except that bread and grain products feature heavily. The less money you have, the more likely you are to eat a LOT of things made out of barley and wheat. Our poorer friends are going to live mainly on bread, soup, salt fish, porridge, eggs, and veggies. A huge portion of the populace is likely to experience a food shortage crisis at some point. But today we’re feasting, so we don’t have to worry about that. Dairy does not play a big role: goat’s cheese and milk is around, but butter isn’t. That’s for barbarians, aka people who are not Greek. Olive oil will be in everything you eat. Fish is popular, as are eels. Yummy. There might also be pork, lamb, goat, and chicken, though these are usually only for festivals and special occasions. The Greeks are excited to throw all sorts of birds in the oven: swans, pelican, crane, pigeon, wagtail. For those who traveled to 19th-century America with me, that last is not to be confused with the slang word for a lady of the evening.

Veggies are fairly plentiful, and you’ll recognize them: cabbage, asparagus, carrots, cucumbers, radishes, pumpkin, chicory, artichokes. Nuts and fruits are also on the table. Salt is here too, though not sugar: we’ll sweeten things with honey and dates.

There’s wine, too, of course: that’s an absolute staple. It’s served watered down and perhaps sweetened in a clay amphora. No beer, though: that’s also for barbarians.

We’ll be wearing a veil the whole time, which has got to make eating a challenge, and sitting apart from the men in our wedding party. Our single table companion will be an older woman, called a nympheutria, who will help guide us through the ceremony, and encourage us to eat some of the little cakes laid out before us. They’re studded with sesame seeds, which are supposed to make us fertile. Because that is the #1 thing everyone in this room wants us to be.

Tom will lead us to his house in a wagon, our dowry strapped down in a chest at the back. The wedding party will follow, singing and playing the flute and generally making a night of it. They’ll be holding up torches, as we have no street lights. We also have no fire service, no public hospitals, and not enough places to stop and pee. Apparently a lot of guys are peeing behind bushes in ancient Athens. Hesiod even gives men some tips on how to urinate in public without offending the gods:

“Do not make water either on the road or beside the road as you go along and do not bare yourself….A good man who has a wise heart sits or goes to the wall of an enclosed court.”

But everyone’s been drinking, so if anyone stops, try not to look at him too hard.

Once we arrive, guests will shower us not with confetti, but nuts and dried figs – hopefully they’re not throwing them directly at us? This is also supposed to make us fertile, and that’s a really important thing for us to be. We’ll say some binding words, then we’ll go into the wedding chamber. Plutarch has advice for us in this moment: chew on a few slices of quince, he says, “in order that the first greeting may not be disagreeable nor unpleasant.” You’re disagreeable and unpleasant, Plutarch, but you don’t hear me giving you advice on how to deal with it!

Tom will give us some wedding gifts. One of them might even be a vase with an erotic scene on it: steamy. Then he’ll lift our veil: this is supposed to be the first time he’s ever seen our face naked, although I’d be shocked if we haven’t had some face time before. Outside, people sing a hymn called an epithalamion, which is supposed to cover up the awkward sounds we ladies are about to make in the bedroom. Mk.

PART 2

So: where were we? Ah, yes: Tom was lifting our veils and getting ready to show off that body he hit the gym so hard for. Not feeling amorous? Never mind that! Your consent is probably optional. A man is the head of the household, and this is a society ruled by gods who take women by force with startling frequency. We can’t presume to know how things actually go down behind closed Greek doors, and Toms’ a gentleman, so we’ll hope for the best. Keep in mind that the expectation is that you’ll be pregnant as soon as humanly possible. And besides, sex is good for you! The top doctors all say so. Like Hippocrates:

“Women who have intercourse are healthier than those who abstain. For the womb is moistened by intercourse and ceased to be dry, whereas when it is drier than it should be it contracts violently and this contraction causes pain…”

MAKING (MALE) BABIES

There is a lot of social pressure coming your way about baby making: you’ll want to have a boy, first and foremost, but a girl will be ok too, I guess. Just not too many of them, as we’ll have to provide them all with dowries! In this age of bad hygiene and confusing notions about how our bodies work, children often die young, so you’ll need to produce a gaggle of them. That way at least a few might make it to adulthood.

You may try and slow down the baby train with potions: herbs, vinegar, woolen pads soaked in honey, cedar resin. In one of Homer’s plays, a character suggests using pennyroyal: a wild plant that would be easy enough for us to find, and will be used for this purpose for centuries to come—even into the 19th century. Though the Hippocratic Oath does say one shouldn’t give a lady a potion specifically to rid her of a pregnancy, it doesn’t seem like abortion is illegal here. One Hippocratic text called the Nature of the Child suggests that a woman wanting to end a pregnancy should jump up and down and click her heels to her rump several times. That doesn’t sound like it will end well for anybody…Aristotle says that abortions should only happen before you can actually feel the baby moving, though this seems less about preserving the child’s life and more about how much pollution a late-stage abortion might cause.

But more than likely, we’ll be actively working to have Tom’s baby. If you do get pregnant, it’s because the man is very virile. If you can’t, it’s going to be called as your fault. Something’s faulty with your womb. There is no such thing as male infertility. I mean, look at Zeus: even his rain gets women pregnant.

The upside is that, once you bring a boy into the world, your household status is getting a definite boost. As matriarch, you’ll get more respect and more deference: until then, hang on tight. You’ll give birth at home, probably surrounded by women. You’ll have a maia, or midwife, to guide you through your birthing pains. A male doctor is unlikely to drop by unless you’re in serious danger: it’ll just embarrass you to have him there, as he’ll have to look at your private parts. For shame!

In this age, anyone can be a doctor – well, any man – as there’s no official certificate. Though there are medical schools like the one run by Hippocrates, who’s responsible for the Hippocratic Oath doctors still swear by in our century. The body of work they’re drawing on is vast and ever-shifting, employing remedies both physical and spiritual. They’re likely to think that our body is defined by four humors: blood, phlegm, yellow bile and black bile. If any of these are out of balance, health problems ensue. Lots of things can impact your health: geographic location, diet, trauma, your general mindset. But they have some funny notions about your uterus. They believe in a female-only illness that we call “hysteria,” which comes from the Greek word hystera, or “womb.” The womb is a mobile creature that is prone to wandering off, causing all sorts of mischief: namely, giving you wild mood swings and a wicked case of the crazies. As Aretaeus of Cappadocia puts it: “It is very much like an independent animal within the body for it moves around of its own accord and is quite erratic.” The remedy: if it’s wandered too far north, put sweet-smelling things by your lady palace to coax it into place. If too far south, repel it home with foul smells. This is, of course, one of the reasons women are inferior to men and can’t participate in politics. For a whole lot more on hysteria through the ages, check out my Patreon bonus episode on the subject.

Hopefully the goddesses are there with you as you birth a child: you’re going to need them. You’ll be placed under the protection of Eileithyia, or “She who comes,” who will help bring your baby into the world. Once it’s delivered, there’s all the pollution to deal with. Having a baby is a dirty business, spiritually, and creates what’s called a miasma that can spread like an infection. What’s that I smell? Lady miasma! Horrors. Pitch is smeared on the walls to try and keep it from spreading beyond the room, and you’ll have to be confined for several days to contain it. Just as well: giving birth in this age is a perilous business. Many women die; miscarriages are common. As Medea says in a play by Euripides, “I would rather stand in battle-line three times than give birth once.”

If a child is unwanted, or it’s sickly, or deemed in some way inadequate, it might be left out in the elements, called exposure. No one in ancient Greece condones killing a child, as such things create pollution, but exposure doesn’t count as murder: it allows the gods to decide the child’s fate. Over in Sparta, parents have to have their newborns inspected by a council, and if they’re deemed weak, the parents have to expose them: by law. You’d be right to suspect that girls are more likely to be exposed than boys. Some estimates put the number of girls exposed in Athens up to 10%. But much of what we know about exposure comes from plays and other works of literature, so we can hope it isn’t actually a widespread practice. And it’s likely there are always childless couples in Athens ready to swoop in and rescue the wee thing from the rocks.

Consider this, too: young girls aren’t generally fed as well as boys are growing up, and they have to go through the perils of childbirth from a very young age. Take a look at the women around you. From what we know, it seems their life span, on average, will be some 10 years shorter than the men of this city. This is not an easy place and time to be female.

On a just-slightly cheerier note: you might entrust breastfeeding your child to a wet nurse. That woman is likely to be a slave. It’ll make you feel uncomfortable to know that slavery is very common here. Slaves come from all over: Illyria, Scythia, Lydia, Syria, won and stolen through piracy, kidnapping, and war. You do not want to be on the losing end of a siege, ladies. Remember the fall of Troy? All of its women would have known what awaited them: abduction, rape, slavery. Not an experience you’d want to time travel back for, but a reality of the ancient world nonetheless. Some estimates say that out of a population of some 250,000 in Athens, a whopping 100,000 of them are slaves. Some are privately owned, some public. Owning at least one is seen as an Athenian citizen’s right. There are plenty of laborers and craftsman who are citizens, but many of the people doing the truly hard labor are enslaved. Hesiod writes that, to truly be a successful farmer, you should have an ox and a “bought woman” beside you.

In Athens, the enslaved are all culturally different, but Athenians still look at them and see one thing: barbarians. Women who serve as oiketai, or house slaves, are always busy: tending to the children, washing clothes, cleaning, gardening, grinding grain, spinning. They work closely with the free women of the household, and it seems like these bonds can be deep and lasting…or so the family’s grave monuments, often carved with their slaves’ likeness, suggests. Less affluent people probably only own a few, while the richest own more like a thousand. As with pretty much all time periods where slavery is present, the number you own is a symbol of your status. And of course, both male and female slaves have little to no rights under the law.

It’s not pretty, but we ancient Greeks seem to accept it as a way of life.

THE ANSWER TO A WIFE? A HARLOT

Back to life with Tom Hiddleston. We are obviously happy with our choice of husband, but that doesn’t mean we have to be stuck with it. Women can get divorced, though they’ll need some male guardian to represent them in court. If you try to stand for yourself, it’s not likely to go well. Plutarch tells a story about how when Alkibiades’ wife tried to testify at court about his many extramarital dalliances, he drags her away by the hair…and nobody dreams of trying to stop him. If you succeed in splitting up, your dowry will be given back, though not to you, but to the male patriarch of your family. And your ex will get whatever he brought into the marriage. No one wants Greek wives to walk away with nothing.

Given the huge age gap in most marriages, it’s pretty common for a woman to end up a widow. If we’re still of childbearing years, we might be expected to marry again as soon as possible. But for older women, this can be an opportunity for freedom and security: a chance to live without everything having to revolve around a man.

And there’s another kind of partnership, called a common-law marriage. It’s very similar to an official marriage, but less binding, because it’s struck between Athenian citizens and resident aliens, prostitutes, or women who have no dowry. The man you marry is still very much in charge of you, just like in a more official arrangement. The difference is that any kids you have aren’t allowed to inherit from the man’s family. Though there are eras when this changes, like during the last decade of the Peloponnesian War, when citizens are allowed to have an official wife AND a common-law one. Several wives living in the same house together has got to make for awkward dinner parties.

So here’s the rub: Tom married you out of duty, and out of the desire to shore up his family line and have tiny Toms to carry on his legacy. But you’ve spent most of your life at home, have gotten little education on either sex or the world, and probably aren’t up for rousing political debates or naughty midnight rendezvous. As our doctors like to say, we ladies have sex only because it’s good for our general health—but men, they crave it just for pleasure. So while sex with us is mostly about procreation, our gentlemen companions still have needs to satisfy—as Xenophon ever-so-gently reminds us:

“Certainly you don’t think men beget children out of sexual desire? The streets and the brothels are swarming with ways to take care of that.”

If Athens has a lot of one thing, it’s ladies of the evening. And it’s socially acceptable for our husbands to spend time with them: slaves, high-class call girls, even young men, all meant as a means to keep men from sleeping with each other’s wives. The penalties for adultery are stiffer in Athens than those for rape: rape is a form of violence, while adultery is a means of luring away a woman’s affection and potentially confusing a child’s parentage. Men who find their wife in bed with another man is allowed to take the guy’s life without fear or punishment. And you’ll be barred from all religious rights: if you show up anyway, the mob’s allowed to do anything they want to you outside of killing you. So…if you’re thinking of sneaking out while Tom’s at the symposium, I’d advise against it.

You certainly won’t be going to the symposium with him.These highly ritualized events are ones Tom will go to often: a place to blow off steam that is part serious frat initiation, part straight-up frat party. Men go there to debate, talk trash, and join in playful buffoonery.

These parties are legendary: they even have an official Master of Drinking, who mixes the water with the wine and sets the pace for the evening. Wine and opium are the popular party drugs of choice. The point is not to get hammered, though people must: it’s to unwind amongst stimulating company. Sometimes there are drinking games, like this ancient version of quarters where everyone flicks wine into nutshells floating in water to try and make them sink. I would have rocked that game. There are women present: dancing girls and flute girls. These are in such high demand that a law is passed regulating how many hours a flute girl can work.

Wives and daughters are banned from these rowdy happenings. But amongst it all float the enchanting hetairai, or “female companions,” making jokes, having opinions, and leaning slinkily against columns to the great delight of the men they’re with.

Hetairai are usually free women who once were slaves, or metics (or non-native Athenians). These high-class escorts are paid a pretty penny to show men a good time. They aren’t the same as common prostitutes, or porne, which means “buyable woman,” who are often still enslaved and owned and run by a pimp.Those who work the streets are a little freer; they also run their own ad campaigns, sometimes wearing sandals stamped on their bottoms with the Greek words for “follow me,” meant to leave a trail in the dirt for prospective clients to follow. Helpful hint: if you’re wearing a copious amount of makeup and open up your own door when someone comes knocking, they’re probably going to assume you’re a porne.

But hetairai are different: they sell their charms and intellectual gifts as much as their bodies.They’re smart, accomplished, and worldly, full of quick jokes and witty banter, because it’s their job to be entertaining dinner dates. That’s going to be a hard bar for the stay-at-home Athenian wife to climb to. As Athenaeus explains: “…is not a 'companion' more kindly than a wedded wife? Yes, far more, and with very good reason. For the wife, protected by the law, stays at home in proud contempt, whereas the harlot knows that a man must be bought by her fascinations or she must go out and find another.”

These women know how to delay a man’s gratification to the point of obsession, and in so doing they absolutely slay. As one hetaira says to a suitor in a collection of imaginary Athenian letters, with what must be a massive eye roll: “I wish that a courtesan's house were maintained on tears; for then I should be getting along splendidly, since I am supplied with plenty of them by you!”

SOCRATES SEEKING ALCIBIADES AT THE HOUSE OF ASPASIA, 1861

Signed and dated J. L. GEROME. MDCCCLXI.

These women spend more time in the public sphere, and have more influence, than most of the women in Athens. Which brings us to a very interesting character: a hetaira named Aspasia. She is one of the only women of this century whose name has made its way to us through the shifting sands of time.

Born in Miletus into a fairly wealthy family around 470 BCE, she seems to have gotten a pretty good education, and she has plenty of opinions she thought were worth sharing. This metic operates her own salon and a girl’s school, which of course her enemies say is actually a brothel. Side note: male citizens can marry female metics, but male metics who want to shack up with a Greek female citizen have to pay 1,000 drachmas: some three years of living wages. Because she’s a metic, Aspasia doesn’t have the same constraints as female citizens, and that gives her an in on the city’s public sphere. As Plutarch says:

“What great orator power this woman Aspasia had. That she managed as she pleased the foremost men of the state and afforded the philosophers occasion to discuss her in exalted terms and at great length.”

The great Socrates apparently comes up with his students to chat philosophy with her, and “marveled at her eloquence.” Great men brought their wives along to listen to her speeches.

Aspasia is so very beguiling that she becomes the common-law wife of a guy named Pericles. He is one of the greatest and best-known politicians of his day. Some say she’s the key to his success in politics: she taught him how to give great speeches. I can just see them now in her fancy bedroom: him practicing his speech, and her being like: “Oh honey, no. Give me that pen. We can do better.” Some even whisper that she herself may have written one of his most famous speeches. Get it, Aspasia!

Of course, there were plenty of heathens who wanted to see her torn down. She was often portrayed unflatteringly in plays, and her name was even found on a lead curse tablet—more on that a little later. She was famously taken to trial for impiety, but Pericles defended her and the charges didn’t stick. After he died, she took a little-known sheep herder as her next husband and groomed him to become a key political leader. Behind every great man is a smart-ass courtesan.

And then there’s a gal named Phryne. Born around 371, this It Girl of the ancient world was quite a famous hetaira. Apparently her name comes from the Greek word for “toad,” which is a little bizarre, seeing as she was a famous beauty. We think her real name was Mnesarete, which literally means “remembering virtue.” As a hetaira, she mixes and mingles with some of the greatest intellectuals and political figures of the fourth century, who are all keen to be in her general proximity. There’s this famous statue of the goddess Aphrodite, carved by Praxiteles, which was said to be one of the most beautiful images of a women ever carved, and the first from ancient Greece. It is modeled after Praxiteles’s then-girlfriend, Phryne. She has some of the most famous breasts in antiquity, which it’s said she was fond of baring as she waded out nude into the sea.

But she isn’t just a pretty face: she’s smart and witty, and so she ends up quite rich: rich enough that she offers to rebuild the city walls of Thebes after they are destroyed by Alexander the Great. Her only condition: that the wall be inscribed with a sign that said it was paid for by “Phryne the courtesan.” My kind of woman.

But like Aspasia, her wanton ways catch up with her. She’s prosecuted for a capital charge, we think impiety, and is defended by the orator (and her lover) Hypereides. As part of her defense strategy, he tears away her tunic to let those famous breasts shine free. Only the Gods, he says to the assembled judges, could sculpt such a body, and thus killing her would be an act of blasphemy. Her breasts are both famous AND legally defensible. Flashing her way to greatness: color me impressed.

So let’s say, back at home, we suspect that Tom’s out cavorting with ladies of the evening, and we want him back at home posthaste. What to do? Well, there’s always magic. Despite how rational we Greeks like to say we are, we aren’t above casting a spell or two if the situation requires it. The Egyptians pioneered it long before we came around, and if the curse ain’t broke, don’t fix it.

Men who want to make a woman come to them will use an agoge spell. These take some aggressive forms, such as piercing a wax effigy with many needles and reading out the following: “Prevent her from eating and drinking until she comes to me…drag her by her hair, by her guts, until she does not stand aloof from me…and until I hold her obedient for the whole time of my life.” Stalker much? We ladies are more likely to use a gentler philia spell to inspire familial feeling. Or you might curse the hetaira he’s with using a curse tablet, writing out your curse on a metal slab, then burying it and hoping for the best. But Aspasia would probably tell us to be friends and stick pins in a doll of our husband instead.

LETTING OUR HAIR DOWN

Have heart, though: as Greek wives, we still have opportunities to make our own fun. During the Peloponnesian War, for instance, when men are gone for long stretches. Vase paintings show women holding their own symposiums. When the men are away, the women will play! And have drunken debates together.

There are also regular, socially sanctioned opportunities to get out and let your hair down: literally. You can actually let your hair down during festivals! Athens has a whopping 170 festival days, many of them religious in nature, during which rules are loosened and women often get to play a starring role.

Some festivals are even exclusively for women. Like Thesmophoria, a fall festival held to honor Demeter, the goddess of the harvest, and her daughter Persephone. Their story is a good one: Demeter is graciously feeding the world by giving them an eternal summer, just living her best life, until the day Persephone goes out picking wildflowers. Hades, Lord of the Underworld, takes a fancy to her and abducts her – because, as we know, the gods are rapey as hell. Demeter is devastated, turning so sad that crops die and the world experiences its first winter. When she finds out where her daughter is, she demands her back, but Hades isn’t keen to return his pretty captive. She goes on hunger strike, refusing to feed anyone until they work out some kind of arrangement, which they do. This is where the seasons come from: the spring and summer mark Persephone’s return to Demeter, while the turn from fall to winter marks her months spent down below.

So it makes sense that men aren’t allowed into this festival. Pack your bags and get ready for a three-day ladies-only rager up at the hillside sanctuary of Demeter. Bye, Tom! We time travelers can’t be 100% sure what will go on in this thing, but here’s what we should go in prepared for: first, the night before the festival, we’re going to a party called the stenia where we’ll insult each other in the foulest ways we can think of. This may be to simulate how Demeter’s friend tried to cheer her up by making fun of her, or maybe just because we have a lot of suppressed rage to let out.

Then we’re going to sacrifice some pigs. Not nice, I know, but the goddesses require it! We’ll put them in a pit called the megaron and let them ripen there for a few days. There may be snakes in this pit, or not…I’m hoping not, because bleh. Meanwhile, we’re fasting, swearing, and perhaps beating each other with bark whips. Hopefully at least one woman has smuggled up a very full wineskin to pass the time. On the third day, women called “bailers” – those who have kept themselves ritually clean during the festival – will bring the pig carcasses up, which we’ll lay on an altar. We’ll also decorate it with cakes shaped like penises: we’re praying for fertility here, after all! Farmers will later take the remains of the pigs and the penis cakes and sprinkle them into their fields as fertilizer. It’s just the thing for making crops grow .

We will also come out of the house when someone dies. Women play a huge role in the ritual cleansing of a recently deceased person, preparing their body for burial. When grandpa dies, we’ll get him ready for the prothesis, or laying out of the body, by washing his body and anointing him with oil. We’ll then dress him and wrap him in a winding sheet, laying him out on a couch so mourners can come and pay their respects.

These occasions of celebration and mourning bring women together, giving them an important role to play and a welcome break from the daily grind.

WE ARE SPARTA

Though the shape of the everyday will change depending on which part of Greece we time travel to, they’re likely to look and feel pretty similar. Unless we’re talking about ancient Sparta, which we’re about to. Because Spartan women have more power and control over their lives than any other women in Greece. Let’s spirit our sandaled feet on over and see what life there is all about.

Why is the Spartan woman so powerful? Because she bears the children and, as Beyoncé would say, “then gets back to business.” In his Sayings of Spartan Women, Plutarch writes that when a woman was asked, “Why is it you Spartan women are the only ones who govern men?” she replied, “We’re the only ones who give birth to men.” These ladies are formidable in more ways than one.

Sparta really comes into its own when it defeats its rival, Athens, in the Peloponnesian War, right around 404 BCE. If these guys know how to win one thing, it’s war. Do you remember that movie the 300, where Gerard Butler and his studly band of heroes whip out their swords, forever showing off their rippling abs? That battle really happened, and the way they paint Spartan life isn’t entirely inaccurate. The Spartans are a militaristic culture that, unlike the rest of Greece, puts the needs of the state above the needs of the family. Think of the word “spartan” (adj.): showing or characterized by austerity or a lack of comfort. Get ready for some sparse living.

From day one, Spartan children have it drummed into them that the #1 lesson is to follow orders and conform. Even kids deemed fit and pleasantly Spartan aren’t going to get much coddling. And because the men are out so much, training and fighting, it’s up to Spartan mothers to get their kids ready for adulthood. As Plutarch tells us:

“Spartan nurses taught Spartan babies to avoid any fussiness in their diet, not to be afraid of the dark, not to cry or scream, and not to throw any other kind of tantrum.”

From the age of seven, boys are sent out to train and learn with their peers as part of a state-sponsored program, going through an increasingly terrifying series of training and hazing rituals. Wimps need not apply. Here’s a charming story for you from our old friend Plutarch: when a bunch of free boys reach the age where they were encouraged to steal to prove their stealthiness and bravery, they stole a young fox. When the owners of said fox come to find it, the boy who happened to have the fox at that moment hid it under his shirt. The fox went crazy, gnawing a hole to his vital organs, but still, the boy won’t make a peep for fear of being caught. When the other boys were like, “dude, that’s sick. Are you CRAZY?” He said it was “…better to die without yielding to the pain than through being detected because of weakness of spirit to gain a life to be lived in disgrace.” Yikes.

Mothers will not be able to complain to the principal when their kid comes home from their lessons bleeding. And they’re unlikely to. Plutarch quotes a Spartan woman who, when her son came home from training about half an inch away from expiring, told her relatives: “Stop your blubbering: he’s shown what kind of blood’s in his veins.”

Such a premium is placed on military fitness that the arts are considered optional: we Spartan ladies aren’t likely to learn how to play the lute, or read, or embroider any cushions. The upside is that we’ll get to go out and train. Unlike elsewhere in Greece, young girls are allowed to mix in with boys freely. We’ll practice running, discus, javelin throwing, horse riding—even wrestling. And we do it in peplos that are scandalously short. “They leave their houses in the company of young men, thighs showing bare through their revealing garments,” says one guy in a play by Euripides. “And – this is intolerable to me – they share the same running-tracks and wrestling-places. After that, should we be surprised if you do not bring up women who are virtuous?”

Imagine the difference such training would make for a girl in this, or ANY, era: exercise means learning discipline, gaining strength, a chance to hone and respect one’s own body. I have a non-historian-approved theory that female liberation and power throughout the ages is tied directly to how much exercise we’re getting. Of course, one of the reasons girls are encouraged to exercise is because Spartans think it’ll make them better breeders. As Plutarch says, it “meant that partners were fertile physically, always fresh for love, and ready for intercourse.” But we do see glimpses of admiration for women who take a more active physical role. Both Herodotus and Xenophon praise societies like Sparta where women run and engage in sports. As Xenophon has it, “if both mothers AND fathers were physically fit their children would be much stronger.”

When you’re old enough, you’ll marry a strapping Spartan youth. You’ll probably be a bit older than your female counterpart in Athens, and lucky you: your husband is likely to be closer to your own age. On your wedding night, you’ll cut your hair short, dress in a man’s cloak and sandals, and wait in the dark for your paramour to come and ritually capture you. Because nothing sets the mood like a little wife-napping! But better be quick in getting down to sexy business: husbands are shamed for spending too much time in bed with their lady, so he’ll have to be back in his barracks before the sun comes up. Spartan men are gone a LOT: they don’t even live at home, but in barracks, which is one of the reasons Spartan women enjoy such freedom. They’re allowed to not only run the home, but own property, and the men aren’t around to get under her feet.

But it’s also because their ability to bear children is so highly prized and respected. Only two kinds of people in Sparta get names inscribed on their headstones: men who die in battle, and women who die in childbirth, because they’re both fallen warriors – both sacrifice their lives for the good of the state. Such a premium is placed on a woman’s breeding prowess that those who prove good at it can be loaned out to other men for that purpose. As long as she consents, gentlemen! At least we hope so.

Such a culture helps create an independent-mindedness that Spartan women are quite famous for. In “Sayings of Spartan Women,” we get a glimpse into how hardcore they are. One woman, when hit on by a foreign man in robes that are apparently a little too womanly, she says:

“You call that a pass? You couldn’t even pass for a woman.”

Married women sing humiliating songs to men who refuse to tie the knot with anyone. Sometimes, it’s said, they even kill their sons if they disgrace themselves in battle. Yikes.

Some Greeks look down on Spartan women, calling them negligent mothers and saying that all the exercise makes them unattractive. Wait…haven’t I heard this argument before about female athletes? I’m squinting at you, commentators of the 21st century! Aristotle thinks their women’s freedom is Sparta’s Achilles heel, because it means the men are “ruled by their wives.” Never mind that those wives are brave, uncompromising, and not afraid to get their hands dirty. They’re warriors in their own right.

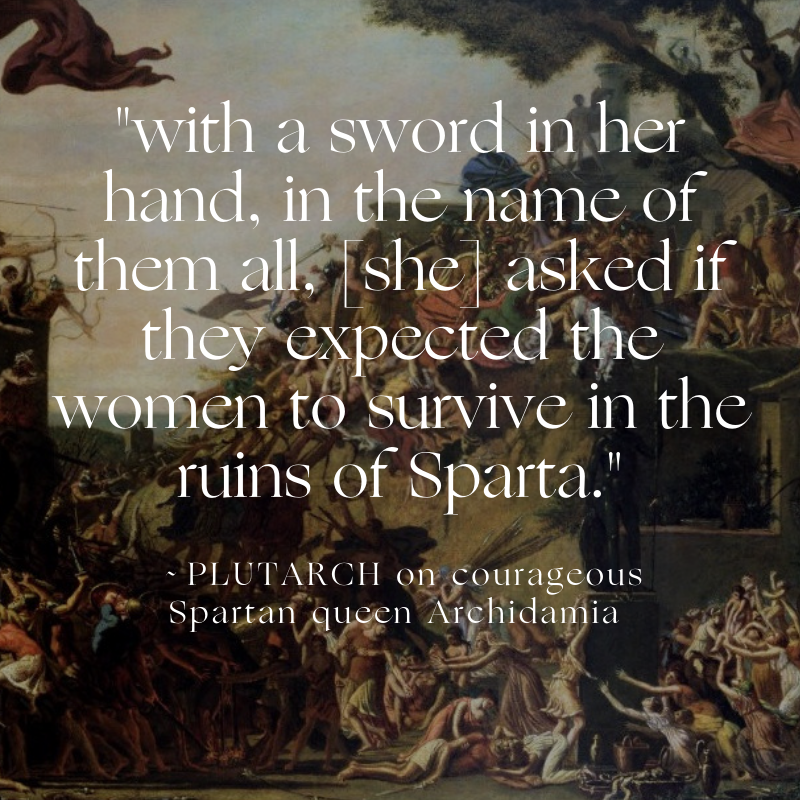

Take Arachidamia. She is a Spartan queen with both wealth and power when the Greek king Pyrrhus decides to take a run at Sparta around 273 BCE. The Spartans are in the middle of a war with Crete, mind you, so most of the men are away from home; only 2,000 are still within the city. And Pyrrhus’ army is not known to take prisoners. So the men left at home decide to send the women to Crete, where they’ll be safe. But Arachidamia is having none of that. She and some lady friends head over to the Senate, says our friend Plutarch, “with a sword in her hand, in the name of them all, and asked if they expected the women to survive in the ruins of Sparta.” They’d stay here and defend their homes, thank you. And the Senate is like, “yeah, ok then. Damn.”

The Siege Of Sparta By Pyrrhus. François Topino-Lebrun, 1799-1800

The ladies help them dig a huge trench around the city, and Plutarch tells us that “When they began to carry out this project, there came to them the women and maidens, some of them in their robes, with tunics girt close, and others in their tunics only, to help the elderly men in the work.”He says the ladies dug at least a third of the trench themselves. Pyrrhus arrives with 20,000 soldiers and many war elephants, which sound kinda cute, but are actually terrifying. If you don’t believe me, go and listen to Ancient History Fangirl’s episodes on them. Pyrrhus thinks the Spartans will probably pee their chitons and beg for mercy right away, but they don’t. They fight. Plutarch says, “the women, too, were at hand, proffering missiles, distributing food and drink to those who needed them, and taking up the wounded.” He fails to mention what I suspect is true: that some of the ladies might also be picking up projectiles alongside their 2,000 gentlemen friends, making it rain spears on spears. And they win. Suck it, Pyyhrus!

CONCLUSION

And with that image of a Spartan lady throwing spears at her enemy, we’ll say goodbye to ancient Greece, for now.

Given how much of Greek history was written by men, we have so few women’s stories. But in the rest of this chapter, we’ll dive into the lives of women who did such extraordinary things that they made it into the annals of history, even if just by their fingernails: making kings, going to battle, sleeping with gods, and writing epic love poetry.

Until next time.

the modern-day site where the oracle of delphi would have spoken many hallucinogenic truths.

Courtesy of Spomenka Krizmanic

MUSIC

Theme music by Paul Gablonski. All other music composed by Michael Levy, who composes all of his work on recreated lyres of antiquity, giving us a special insight into what ancient music might have sounded like. Provided and licensed by AKMProductionsInc.com.

VOICES

Katy and Nathan from Queens podcast

Genn and Jenny from Ancient History Fangirl

Shawn from Stories of Yore and Yours

Andrew Goldman

Phil Chevalier

John Armstrong

Avery Downing

Simon Dinatris