Something Wicked This Way Comes: 19th-century Spiritualist Mediums

You’re sitting at a big, round table in someone’s dining room.

It’s dark outside the windows – the only light comes from the many candles, glinting off jewellery and casting shadows over people’s eyes. Everyone joins hands; someone starts singing a hymn, and you join in. The sound of it slides across the floor, up the walls, vibrating through you. Then young woman across from you lays her hands upon the table, fingers spread wide. “Are there any spirits here?” You wait. And then you hear…a rapping.

The spirits are among us.

“Is it you, Aunt Ida?”

RAP RAP RAP.

You don’t understand what they’re saying, but the woman across from you does. She is the medium. The conduit through which the dead are to speak.

New, controversial and powerful, Spiritualism swept like wildfire through America – whether you were a believer or a skeptic, you couldn’t ignore it. It was everywhere. The notion that the spirits of the dead weren’t gone, but all around us. And they could be reached through a medium, who was almost always a woman. Mediums offered people solace, entertainment, and proof of an immortal soul. But Spiritualism also offered women a way to escape the strict societal ropes that bound them. It literally offered them a seat at the table, giving them a voice—and the power to use it.

And many did, on stages and in parlors across the country. Even the White House saw its fair share of late-night seances. Ghosts were alive and well in the 19th century, but what made the Victorian era so haunted? And what gave ladies ownership over the business of talking to the dead?

Grab your black veil, a planchette, and some smelling salts. Let’s go traveling.

My sources

books

Radical Spirits: Spiritualism and Women's Rights in Nineteenth-Century America, Second Edition. Ann Braude, Indiana University Press, 2001.

Women, Religion, and Social Change, edited by Yvonne Yazbeck Haddad, Ellison Banks Findly. State University of New York, 1985.

This Republic of Suffering by Drew Gilpin Faust, Vintage Civil War Collection, January 2008. This is a beautiful, award-winning book about how the Civil War changed the landscape of grieving and rocked America in countless ways that you may never have thought of. It’ll rock a history nerd’s socks right off.

podcasts

“Jewelry of Sentiment, Part 1: The Art of Hair Work & 2: an interview with Courtney Lane.” Dressed: A History of Fashion.

“The Disappearing Woman: Adelaide Herrmann, Queen of Magic.” What’s Her Name Podcast.

“Victoria Woodhull: Free Love, Feminism & Finance.” DIG History Podcast.

“Mediums.” Historical Hotties.

online

“In the Joints of Their Toes.” Edward White, The Paris Review, November 2016.

“Samuel Morse and the Invention of the Telegraph.” Mary Bellis, ThoughtCo.com (History & Culture), July 2017.

“The Shape of Your Head and the Shape of Your Mind.”Erika Janik, The Atlantic HEALTH, January 6, 2014.

“Scratch Marks on Her Coffin: Tales of Premature Burial.” Ella Morton, Slate.com.

“Women's Mourning Customs in the Civil War.” Maggie McLean, Civil War Women Blog.

“Mary Todd Lincoln, Spiritualist:Did the first lady’s supernatural interests convince Abraham Lincoln to sign the Emancipation Proclamation?” Mitch Horowitz, Medium.com, July 17 2018.

“Trendy Victorian-Era Jewelry Was Made From Hair.” Becky Little, National Geographic.com.

“The Strange and Mysterious History of the Ouija Board: Tool of the devil, harmless family game—or fascinating glimpse into the non-conscious mind?” Linda Rodriguez McRobbie, Smithsonian.com, October 27, 2013.

“The Fox Sisters and the Rap on Spiritualism: Their seances with the departed launched a mass religious movement—and then one of them confessed that ‘it was common delusion.’” By Karen Abbott, Smithsonian.com, October 30, 2012.

“The Photographer Who Claimed to Capture Abraham Lincoln’s Ghost.” Dan Piepenbring, NewYorker.com, October 27, 2017.

“How the Victorians brought famous artists back from the dead in seances.” Michelle Foot, The Conversation, July 22, 2016.

“The medium is the messenger: meet the new breed of American spiritualists.”Kim Kelly, The Guardian online, November 8 2016.

“Antebellum Spiritualism and the Civil War.” By Kyle Schrader, Gettsyburg Compiler, 2015.

“22 Morbid Death and Mourning Customs from the Victorian Era.” Lisa Waugh, Ranker.com.

“The Spiritualist Medium: A Study of Female Professionalism in Victorian America.”R. Laurence Moore, American Quarterly Vol. 27, No. 2 (May, 1975), pp. 200-221. The Johns Hopkins University Press.

“Ghosts in the Machines: The Devices and Daring Mediums That Spoke for the Dead.” Lisa Hix, Collectors Weekly, 2014.

“Spirits in St. Louis.” Christopher Alan Gordon (Director, Library and Collections), Missouri Historical Society. Oct. 31, 2017.

“The Sisters Who Spoke to Spirits.” Ada Calhoun, Narratively.com, September 2, 2015.

“How Contacting the Dead Became a Family Game.” Smithsonianmag.com

Bonus Episode Resources

If you’re keen to listen to a bonus episode about murderesses and the girl who loved a husband assassin, check it out over on Patreon.

“Lucy Lambert Hale and Her Mysterious Valentine of 1862” and “Lydia Sherman the Derby Poisoner Commits the Horror of the Century.” New England Historical Society Website.

“Was Mary Surratt a Lincoln Conspirator? The southern widow’s Maryland house was a crucial stop on the escape route for assassin John Wilkes Booth the night he shot the president.” Video (4:20). Smithsonianmag.com.

“The Enduring Enigma of the First Woman Executed by the U.S. Federal Government.” History, TIME.com.

The Mary Surratt Museum website.

Lydia Sherman. Murder by Gaslight.

Victorians were ready and willing to be haunted.

An 1888 Illustration from Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Weekly.

transcript

i do some writing, riffing, and editing while I record, so this may not be verbatim…but it’s close. please forgive any typos! I know, I know.

Let’s start in Hydesville, New York on March 31, 1848. This is when Spiritualism really takes off. We’re in the house of two teenage sisters – Kate and Maggie Fox. Their mother Margaret is getting very freaked out by the ghost the girls claim is trying to communicate with them. It keeps rapping loudly on the walls and floor.

They tell a neighbor that they’ve made contact with a spirit, the devil whom they call Mr. Splitfoot. But the neighbor doesn’t believe them. Come on over! They say. See for yourself! And so the neighbor does.

The sisters climb into bed, their mother hovering close.

“Now count to five,” one says. And what do they hear? Rap, rap, rap, rap, rap.

“Count fifteen,” one says. The spirit obliges. It even raps out the neighbor’s age; thirty-three.

They are invited over by some other excited neighbors, Isaac and Amy Post, who ask that they try and reach the spirit of their dead daughter. The Posts have a lot of friends in high places, whom they invite over to partake in this phenomenon.

At first, the raps are a binary system: just yes and no. But Isaac works out a handy alphabet system so the dead can spell out whole words and sentences. Everyone is talking about these girls and their communion with the dead.

Soon the girls are taken to New York City’s Barnum’s Hotel, where they begin offering three seances a day at $1 a pop. They are an immediate sensation. Spiritualism – the belief that we can reach the dead and talk to them – has arrived, and in a big way.

But why is 19th-century America so obsessed with being haunted?

Spiritualism’s first stirrings developed in Austria with an 18th-century healer named Franz Anton Mesmer, who concluded that all living things had magnetic fluid inside them. The planets sent out invisible rays that effected the flow of that fluid, in a phenomena he called ‘animal magnetism’. If you harness that magnetism with metals like iron and minerals, applied while a patient is in a “mesmerized” hypnotic state, you can actually control the body. You can use that magnetism to heal it. He became quite the big deal with this theory, treating guys like Wolfgang Mozart. When some people awaken from a mesmeric trance, they claim to have experienced visions of spirits in some dimension. Not in ours, but close to it.

Meanwhile, Swedish mystic Emanual Swedenborg seemed to know an awful lot about the afterlife. He said there were three heavens, three hells and a middle plane—the spirit plane, which is very much like the world on earth.

It doesn’t really take off until Andrew Jackson Davis starts hearing spirits from a very early age. In 1844, after putting himself into a mesmeric trance, he wanders into the mountains, where our friend Swedenborg’s spirit speaks directly to him. He writes the messages down, verbatim, in his 184. Revealing that the spirit world isn’t a static place, but one that moves: one that can be reached into and wandered out of. There isn’t just one Heaven, one Hell: there are spheres, and spirits can move up and down them. Which means that death isn’t an ending, but an evolution. A new state of being.

Alrighty. But how did it work its way into the Christian public’s consciousness?

Remember that we’re living in a world of defined spheres – the public one, where men vote and work and make decisions, and the private sphere, where women raised children and clean and have hysteric breakdowns. Remember that we’re living in a very Christian society, and we women are considered moral pillars – guiding lights to keep us all on the pure path. And so women are an important part of the family and community’s spiritual life, including in the church—it is one of the only public places they exercise real power in. But as a rule, women aren’t allowed to be clergy, and they’re not allowed to serve in high church positions. No no, ladies—it’s not for YOU to talk in church. The Bible says so! Just sit quietly and listen to this old man tell you how to save your soul. Riiiight.

A lot of people, men and women alike, are losing faith in the rigid, fire-and-brimstone, you-were-born-already-sinning-and-separated-from-grace model. Many of these are liberal-leaning reformers who feel that Protestant churches aren’t holding up their end of the spiritual bargain. They aren’t helping restructure constricting roles for men and women; aren’t helping women get the vote; aren’t emancipating slaves. They’re just holding up the status quo.

Spiritualism takes a different approach. Instead of saying that souls are naturally sinful, it says that souls are naturally divine – that all of us have an inner light and connection to the spiritual. The soul can be a bridge between this life and the hereafter. Doesn’t that sound nice?

“Still monstrous evils afflict the dwellers of the earth,” wrote Cora Wilburn, a well-known spiritualist of the day. “…and as the Bible fails to apply the remedy, must there not be a higher and a safe guide? There is...in the human soul.”

Things are changing quickly in America. This is the era of Charles Darwin and his evolutionary theory, of the beginnings of electricity and the fast-moving train. America is moving swiftly toward industrialization: it’s on the cusp of flushing toilets, bicycles, typewriters, bullets, lights that turn on and off without the use of a match.

You’d think technology would blow the lid right off this talking to spirits business. But to most people, all this science stuff feels like magic. Communing with spirits feels about as probable as sending invisible messages through wires.

Take the telegraph. In 1842, a guy named Sam F.B. Morse put a petition for $30,000 before Congress. Years earlier, while away on business, Morse found out that his wife Lucretia had fallen ill. But by the time he got home, she’d already been buried. Apparently his heartbreak over getting the news too late was part of what inspired him to look into long-distance communication. It may even have pushed him to invent the electric telegraph, and develop the Morse code that bears his name.

The first telegraph Morse ever sent, which reads: “What hath God wrought?” Which is a great first line, but also a little haunting. Courtesy of the Library of Congress.

In 1842, he wants to build an experimental telegraph line between Baltimore and Washington. But it’s actually laughed at on the Senate floor. A guy fabulously named Cave Johnson gets up and says that, what the hell, if we’re going to throw money at that, why don’t we chuck some at the mesmerists! And how about some for those Millerites, who are predicting that Christ will rise again in 1844? Oh, how everyone laughed.

Electricity won’t really become a thing until 1882, and even then most people use oil lanterns well into the 1920s. The idea of messages shooting through the air, invisible, seems like some kind of dark voodoo. And I mean, it makes sense: it’s invisible, unfathomable. Just like talking to spirits.

In fact, Spiritualists use the telegraph to help explain how they work their magic. One medium said that spirit communications flowed “from mind to mind, as electric fluid on the telegraphic wire.” That’s how spiritualists explain why spirit circles should be formed of equal parts men and women. It’s about creating a harmonious sort of ‘charge’ between women (the negative charge) and men (the positive charge).

And there are plenty of new sciences that rely on the invisible and interpretive. Sociology, for one; anthropology for another. And of course you have phrenology, the art of fondling head lumps, which can tell what kind of person you are. Phrenology actually helps ‘prove’ that men and women are equals. Lydia Fowler, one of the first women to get a medical degree in America, gives enthusiastic lectures on it—to audiences made up almost entirely of women.

The idea that we can talk to spirits isn’t some weird offshoot of science: leading minds of the day take it seriously. Alfred Russell Wallace, co-founder of evolutionary theory, is a fan. Later in the century, he’ll be ridiculed for being so enamored with Spiritualism. But like many, he sees it as worthy of scientific study:

“ The whole history of science shows us that whenever the educated and scientific men of any age have denied the facts of other investigators on prior grounds of absurdity or impossibility, the deniers have always been wrong.”

And so instead of damning spiritualism, in some ways the rising tide of science helps make room for it.

Science is illuminating things, but it’s also confusing things in a fast-changing time. We’re seeing this massive shift from agricultural to industrial – from individual makers to mass production. Technology is speeding up the pace at which we live, and that has people reaching for answers, wanting something to hold onto amid the mad rush of the times.

The church isn’t offering answers, but we’re not quite ready to embrace science either. Neither of them can altogether cure what Abby Sewell calls the “disease of a starved heart.” But perhaps the spirits of those on an elevated plane might help us. Plus, spiritualism provides scientific ‘proof’ of something a lot of people yearn for: that the soul actually exists.

Plenty of men are involved in the movement, but it’s really women like the Foxes who bring it exploding into the mainstream, and women who drive the demand for it. Why? Because it turns out that Victorian ladies have plenty of reasons to want to be haunted.

VICTORIANS AND DEATH

In Victorian America, death is never far from our hearthstones. Most people will only live into their 40s, and that’s only if malaria, cholera, childbed fever, or 19th-century medicine don’t take us first.

In this century, we have a much more intimate relationship with death than in the 21st. So it’s no wonder that taphophia is a common affliction: the fear of being buried alive. With illnesses that put people in a coma-like state and doctors unable and unwilling to do more than poke you a few times and maybe shout your name loudly, it’s hard to know for sure if someone’s dead. There are ways to test, besides the obvious: for instance, your doctor can give you a compressed smoke enema. You didn’t think we’d make it through without at least one enema, did you?

Victorians are so worried about being buried alive, or vivisepulture, that southern gent Edgar Allen Poe writes a terrifying short story about it. In The Premature Burial, a guy becomes obsessed with worry over the possibility. “The boundaries which divide Life from Death are at best shadowy and vague. Who shall say where the one ends, and where the other begins?”

Edgar Allen Poe: kinda freaked out about that whole ‘being buried alive’ thing that happened with some frequency during his century.

Illustration by Harry Clark, from the 1919 edition of Tales of Mystery and Imagination.

Sometimes the dead are put in waiting mortuaries, which are kind of like hospitals, where attendants watch and care for the deceased in case they revive. For people who want to take no chances, there are safety coffins. They’re rigged with air tubes and handy bell and pulley systems. So if you wake up sweating in a tiny box, don’t claw the woodwork! Just ring the bell and wait. Someone will find you before you run out of air…probably.

We also have to worry about so-called “resurrection men”, or grave robbers, which are apparently quite keen to dig up bodies and sell them to eager medical students. Sometimes they even ask women to act as bereaved family members, claiming bodies from poor houses and crashing funerals to try and ascertain the state of a grave. Not cute, ladies!

Budding doctors of the age are very keen to study human cadavers, and apparently donating your body to science isn’t yet a thing. So grave robbing becomes such an issue that states pass Anatomy Acts to keep student’s grubby hands out of gravesites.

In a very Christian society, where mourning is an ornate and intimate ritual, and in which we believe that if dirt touches the body your soul can’t rise to heaven, this is…unseemly, to say the least.

And then there’s this. Some 40 percent of children are dying by the age of five. That’s almost half of America’s children–sadly, that number grows amongst the poor and the enslaved. The women we’ve traveled with this season are all so different, but they have this one horrifying thing in common: virtually all of them, from secret lady soldier Emma Edmonds to confederate spy Rose O’Neal Greenhow, loses at least one child to illness. The church will have you believe that death is a final ending. Next stop: either heaven or hell. The end.

As one pamphlet handed out to soldiers during the Civil War said, “What you are when you die, the same will you reappear in the great day of eternity. The features of character with which you leave the world will be seen in you when you rise from the dead.”

But Spiritualism proposes an alternative line of thinking: that our children are hovering just beyond us, watching us. That the afterlife is beautiful, and that souls evolve and grow and live on.

Take Horace Greeley, editor of the New York Tribune and big fan of the Fox sisters. He and his wife lose SEVEN children. It’s under that black cloud in 1850 that his wife persuades him to go and see phrenologist Charlotte Fowler Wells, sister-in-law to our doctor friend Lydia. At her weekly seances, her brother performs a feat called “automatic writing”, where he goes into a trance and writes down messages from the dead. Imagine how desperately you’d want to speak to your children, after having lost them. To make sure they’re at peace.

Remember, too, that this is a sentimental age – a romantic age. It’s also the age of American gothic fiction. Edgar Allen Poe wrote his story The Tell-Tale Heart, about a heart beating under someone’s floorboards, in 1843. But before that, back in the 1820s, 18-year-old Poe joined the army and spent some time outside of Charleston, SC. It’s there that, legend has it, he fell in love with fourteen-year-old Anna Ravenel. But it was a forbidden love. They apparently had clandestine meetings in a local graveyard, until her father found out and locked her up in their house. But it was hot in Charleston that summer. Anna contracted some kind of illness, and she died. The heartbroken Poe wasn’t allowed to attend her funeral – Anna’s father even kept her burial place a secret from him. But Poe never forgot his young lover. His last poem, “Annabel Lee,” is said to be based on her. In 2017, I went on a Charleston ghost tour to the Unitarian Church Graveyard, which is where she supposedly does her haunting. All I can report is that she did not appear to tell me whether Edgar was an excellent kisser or not.

Victorian Americans are gothic Americans. They turn mourning into an art form; and that art form is, primarily, a woman’s realm.

It’s women who sit by sick children’s bedsides to nurse them—they don’t go to hospitals. Before the war, less than 15% of people die outside the home. They die in bed, surrounded by loved ones who can hear their final confessions. It’s women who wash their bodies and arrange their funerals, also held at home. Clocks are stopped at the time of someone’s death, silenced so as not to encourage their loved one to stick around and haunt them. Anything reflective or shiny is covered, including all mirrors and glass.

With the advent of photography, many families start taking pictures of their dead, called post-mortem photography. Children are often dressed and posed like they’re still living, propped up with books and things in their hands. Sometimes the family even poses with them. Which is…yes. It’s a little much for me, too.

All of these rituals are part of the notion of the Good Death: a way of dying, and of mourning, that is central to the world we’re currently traveling through. There are instructional booklets on the art of death and mourning, and many are aimed at women. Death and mourning fall very firmly in the woman’s sphere.

And we take our duties seriously. There are strict codes for mourning, particularly in the realm of dress. You’ll start in deep mourning – wearing all black – then move on to full mourning, where you’ll add some white ruffs and a collar. Then you’ll have half mourning, where you’ll wear lavender and grey, but nothing bright and flashy.

Men, with their need to go out and run things, I guess, tend not to wear mourning clothes for long: they grieve a spouse for three months, and often just by wearing a black armband. But women stay in mourning for much longer. Over a child, a year, a sister, six months, a widow for two and a half years. This in a time when spouses and children are dying with some regularity. So, ladies, I sure hope you like wearing black.

Nannie Haskins apparently looked great in it. After her brother died in the Civil War, she wrote with indignation about being complemented on how fetching she looked in her mourning clothes: “Becomes me fiddlestick. What do I care whether it becomes me or not? I don’t wear black because it becomes me…I wear mourning because it corresponds with my feelings.”

And that’s something I appreciate about this ritual: mourning clothes are grief made visible. All people, familiars and strangers alike, have to do is look at you to know you’re experiencing grief. Over in England, Queen Victoria really set the trends by grieving more aggressively than anyone. After her husband Albert dies in 1861, she wears all black for the rest of her life.

Queen Victoria: girl knew how to mourn in style, that’s for sure. After her husband Albert died, she wore black for the rest of her life.

Wikicommons.

But we Victorian ladies take deathwear even further. We are quite wild about making jewelry out of dead loved one’s hair – called hairwork. Earrings, brooches, hair clips, you name it: grandma’s hair makes quite a lovely barrette!

Many are created by ladies at home, with a few tools and some expert braiding skills. They’re incredibly intricate: check out my Instagram to see a few of them. And while this may sound gross to our modern ears, they’re kind of beautiful. And sweet, if you think about it. Your mom kept your first lock of baby hair in an envelope, after all—at least mine did. Why not make it into a beautiful expression of your love?

Death and mourning happen in the home, so it makes sense that spirits, and communing with them, also happens there. It also makes sense that communing with them is seen as feminine. As spiritual writer Cora Wilburn said: “the medium may be man or woman--woman or man--but in either case, the characteristics will be feminine.”

Spiritualism performs a very neat trick on women: it takes what in other contexts is seen as her weakness – sensitivity, passivity, impressionability – and turns it into something powerful. Spirits need someone to communicate through, a vessel, and women are sensitive. They’re closer to the divine than men.

Sure, in the past, women were also believed to be more susceptible to demon possession (Salem witch trials, anyone?), but that means they’re also more susceptible to angels. And that, it turns out, grants us its own special kind of power.

RADICAL TRAILBLAZERS

Spiritualism is WAY ahead of its time when it comes to social reform and female power. That's because they believe firmly in individual sovereignty. A female medium needs agency – control over her body, her mind, her life – if she is to channel the divine. In this way, communing with spirits is almost an act of womanly defiance.

This movement puts men and women on equal footing: you need harmony between them for spiritualism communion. It doesn’t just give women a seat at the table. It puts them front and centre, using their voices in a whole new way.

Spiritualists are radical reformers, abolitionists, and suffragists – people who don’t like the world as it is and aren’t afraid to say so. Some of their views are radical enough that they make even the founding mothers of the suffrage movement, Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony, fan their faces.

But when the landmark Seneca Falls convention in 1848 come around, the first for women's rights, the spiritualists are there in force, giving speeches on a woman’s right to control her body and use that body to commune with the spirit. Cady and Susan had to admit, in their book History of Woman Suffrage:

“...the only religious sect in the world that has recognized the equality of the woman is the spiritualists.”

Communing with the dead and women’s rights: what a delightful pairing!

It isn’t hard to see what women first so attractive about it. First, because of how it exalts women. But also because anyone can participate in spiritualism – and the spirits can choose to speak to you no matter where you come from. A 12-year-old girl from a farming family, or a 70-year-old socialite in Boston, or an African American mother in Washington all have an equal chance of finding their spirit guides. And so the movement is popular throughout all social strata, and you don’t have to be an expert to perform seances. They often happens at home.

Let’s set one up in our parlor, shall we? First, grab that heart-shaped piece of wood called your planchette. Picture an early version of the Ouija board, which will come out at the end of this century. The planchette is a little placard we’ll put our fingers on. The spirits will move it, either pointing at letters or, if we’ve inserted a pencil into it, will write down messages from the beyond. That’s a much faster way to get answers than trying to decipher a series of raps!

Let’s try it. Spirits, will I ever have a torrid affair with Tom Hiddleston?

Y-E-S!

But some mediums turn their special skills into a proper business. By far the most famous ones are teenage girls.

Why? Well, for one, because young girls are considered innocent: a pure vessel for a spirit to pass through, and too unspoiled (as of yet) to lie and deceive. Plus, there’s something kind of thrilling about seeing a young girl up on a stage, by herself, commanding audiences. Especially for our male viewers, whom we normally tell to avert their gazes from women they don’t know well.

These public medium displays aren’t that unlike the era’s popular “living statue” shows – you know, that Victorian phenomena where men pay to watch a half-nude woman posing up on stage like a model in an art class – except, you know, this is different. It’s godly. And it’s something most Victorians never have seen before.

So let’s go back to the Fox sisters in that hotel in New York, now joined by their older, married sister Leah. All sorts of people come by to see them speak to spirits, both out of curiosity and because they want to prove that they’re frauds. From the beginning, they’re met with much scrutiny. After one of their first demonstrations, a so-called “Committee of Ladies” takes the girls into a private room and makes them strip to prove they aren’t hiding any gimmicks under their dresses.

Female mediums are always having to prove they’re not frauds, and they do to many people’s satisfaction. And if they are frauds, you can’t blame them for it. The Fox gals are making some $90 a day for their seances, in a time when most girls their age make $8 a month if they’re lucky. Kate Fox becomes so popular that she’s hired by the Christian Spiritualist to give free seances. She makes $1,200 annually: a sum that puts her head and shoulders above most women, into the realm of what Clara Barton is making during her time at the Patent Office and what Sarah Emma Edmonds is making selling Bibles: remember, she has to pretend to be a man to make that kind of cash. The more famous spiritualists draw huge crowds, many admirers, and a kind of financial independence that most girls can’t even dream of.

So of course, after the Fox sisters, there’s an explosion of lady mediums. And there are plenty of people who want to put them through their spectral paces.

For instance, in 1857, the Boston Courier sets up a $500 prize to any medium who can demonstrate paranormal ability to their group of experts, a challenge the Fox sisters accept. They are examined by three Harvard professors, who promptly fail them. But that doesn’t seem to slow down their reputation much.

Many famous and influential people come to see them: poet William Cullen Bryant, writer James Fennimore Cooper, famous abolitionist William Lloyd Garrison, and newspaper publisher Horace Greeley. He said, after having them in his home:

“Whatever may be the origin or cause of the rappings, the ladies in whose presence they occur do not make them.”

All of the Stowes, including Harriet Beecher Stowe of Uncle Tom’s Cabin fame, are big fans. Harriet is somewhat skeptical, but apparently the possibility of speaking to her deceased children is just too great to pass up. Dashing surgeon and Arctic explorer Elisha Kent Kane comes on down, hoping to prove they’re frauds, but he can’t do it. “After a whole month’s trial I could make nothing of them,” he said. “Therefore they are a great mystery.”

And we know how men love a mystery. He’s particularly taken with the middle sister, Maggie Fox. She and this dashing, thirty-something tomcat carry on a secret courtship for years, and then a secret marriage. He loved writing her condescending letters about how she should make sure to stay pure for him. “Night has come…yet I sit down…to show my dear little Maggie that she is not forgotten…Do, dear darling, be lifted up and ennobled by my love.” But then, while on a boat to St. Thomas, he has a stroke and dies. Maybe the spirits cursed him!

The Foxes are even invited to the grandest house in the land: the White House. First Lady Jane Pierce brings the sisters over to the Presidential mansion to conduct a séance after she loses her 11-year-old son, Benny. Poor Jane actually saw him die in a train accident, killed by piles of falling luggage. What a way to go.

But it must have brought her comfort. Afterward, she writes to tell her sister than Bennie visited her in dreams two nights in a row.

The Fox sisters are very much like the child actors from our century: coddled and given all sorts of wild freedom. They’re drinking wine and flirting. But like many child actors, they’re also an object of constant want and fascination. This state of being won’t end well for them in later life. But for now, it also gives them a unique kind of power. Remember when your English teacher made you read The Crucible? How those girls hopped out of bed, rose up against their repressive culture and started accusing people of being witches just because they could? That’s what I think of when I think of these girls. Drunk on the power to heal and help and command attention. But also, perhaps trapped in the fame they created for themselves.

The Foxes aren’t the only famous young mediums to charm the pants off their customers. Beautiful, teenager Cora Hatch does so as well—many times. She is a well-known “trance lecturer”: that’s when women get up on a stage, go into an unconscious state, and let the spirits speak through them. This whole trance lecturer thing is worth lingering over. This is a time, remember, when women leading discussions and speaking up on public stages is hugely controversial. It’s okay for women to speak in private groups, and to all-women listeners, but in public?...and in front of men?! Horrors.

Though the abolitionists and the suffragists often supported each other, campaigning together, this issue of women speaking on stage to mixed audiences is something many of them split over. Even super progressive institutions balked at ladies on stage. In 1847 at Oberlin College, which our friend Sarah Emma Edmonds will later attend, student and suffragist Lucy Stone is elected by the student body to give the commencement address. But the university won’t let her. She can write it, you know, but a male professor will need to read it for her! A lady saying smart things in public: now that’s racy.

But trance lecturers are an exception. They say what they want in front of audiences of thousands, and get away with it, because of course it isn’t really THEM saying it. It’s the voice of the spirits who have taken them over. As one rapt guy said of a trance lecturer’s performance, “That a young lady not over 18 years of age should speak for an hour and a quarter, in such an elegant manner, with such logical and philosophical clearness” pointed to “a power NOT natural to the education or mentality of the speaker.”

And though these women aren’t often talking about suffrage up there on stage, they are speaking in public with eloquence and poise, proving that a woman can do so—and make serious money while doing it. Many women in the audience are struck by this, and write these mediums heartfelt letters of thanks for what they’re doing. These mediums are pioneers: they blaze a trail for the female speakers who come after them. Years later, when Clara Barton goes out on the lecture circuit, it’s lady mediums who helped pave the way for her success.

FAMOUS MEDIUMS

Trance lecturer Cora Hatch enthralls her audiences. She was marked from an early age as in touch with the spirits. She was born with a caul over her face: a membranous veil that some thought meant she had special powers. She certainly has the power to charm people. By the age of 15 she is owning the stage, calmly answering pressing questions from the audience, like “Was Jesus of Nazareth divine or human?”

With the help of spirit guides, she talks about all manner of subjects not usually considered suitable for women. But at the same time, she seems so childlike, so innocent, which only impresses her audiences all the more. “Many times, almost numberless, I had experienced the wonderful consciousness of being absent from my human form,” she wrote in her book My Experiences While Out of My Body and My Return, After Many Days, “…of mingling with prison friends in their higher state of existence.”

But her sainted halo is dented somewhat when, at 16, she asks for a divorce from the first of her four husbands. Benjamin Hatch, her husband and manager – is 30 years old than her, which is cute. She files for divorce for what she claims is his financial and sexual abuse. You think it’s hard for a woman to speak out against her abusers now? Imagine it in the 19th century. But the progressive spiritualist community, and the many suffragists involved, speak up for her. Where divorce might have ruined the prospects of some women of this era, Cora continues to travel and make money on her own.

Some people even think spirits can cure the serious ailing. It’s so powerful that it can bring long-term sufferers up out of their beds. Olivia Langdon lay in bed for two years after falling on a patch of ice. Sick of doctor’s useless suggestions and desperate for help in any form she could find it, she turned to a spiritualist healer. She came and prayed over her, and it cured her. She will later go on to marry Mark Twain.

Achsa W. Sprague is also miraculously healed of debilitating illness by spirits. She is so convinced that her spirit guides healed her that she feels called to bring their message to the public. She spends the rest of her life giving talks and writing for spiritualist publications on topics like abolition and women’s rights.

Acsha sprague was brought out of her bed by spirits. She found her passion in helping them heal others, too. That, and causes like suffrage and abolition.

Courtesy of the Vermont Historical Society

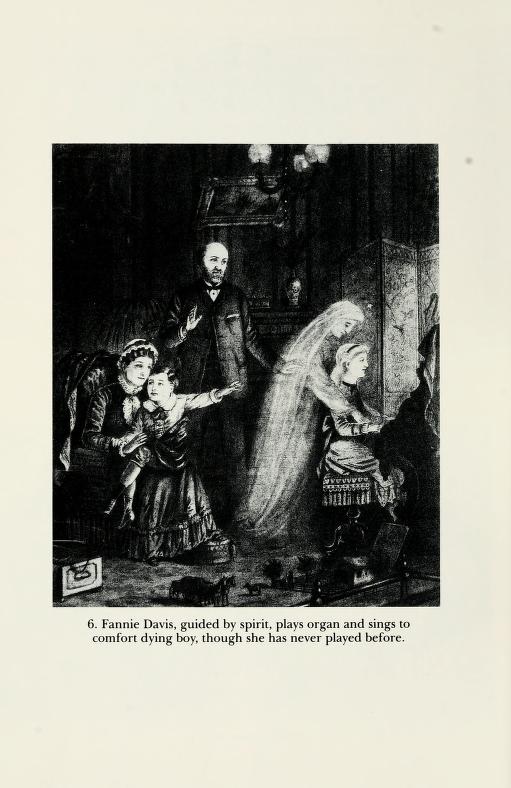

As time went on, other mediums grow more sophisticated: there are reeling chairs, levitating tables, papers emerging from under tables covered in the handwriting from those long dead. There are writing mediums, who take down ghostly dictation.

There is spirit music, too: mediums sit at the piano, though they say they can’t play a lick, and let ghosts come and play through them. There’s even something called a spirit trumpet, used to magnify the whispers of the spirits. Over in England, artistic mediums like Georgiana Houghton painted beautiful works of art while in a trance-like state, said to be inspired by the spirits around them.

These mediums take the practice of talking to spirits and turn it into a profession, making it one of the only – and most lucrative – professions that a woman can hold.

Of course, there are skeptics who object to this. Guys like Ralph Waldo Emerson think the whole thing is a dangerous sham. But it seems like most mediums believed, at least partially, in what they’re doing. And they believe in their right to do it for profit. One wrote:

“If my mediumistic fit is the one most in requisition, it is no less worthy of being exchanged for bread than any other.”

Some of these women get served a heaping pile of derision for what they’re doing. But many of them feel called to do what they’re doing. They think that they are offering an important public service—and when the Civil War comes, that service is more in need than ever.

THE CIVIL WAR

Before the war, death in Victorian America is a fairly well known companion. But at least most people die at home, surrounded by their families. But when the war comes, young men start dying in their thousands. Worse than that, they’re dying abruptly and far from home.

It’s hard to underscore what a huge, horrifying shift this is for 19th-century Americans. Dying at home is an important part of the Good Death: that way your relatives, and especially the female ones, can be there for your last confession, to wash and dress your body and help ensure that they will see you again in heaven. That’s why so many of them are found on the battlefield still clutching pictures of their female relatives, and letters filled with half-finished last words. So imagine finding out not only that your husband or son has died, but that no one knows where they’d buried. The utter abruptness of a life cut short.

Women spill their feelings onto the page, trying to understand loss on such an overwhelming scale. Many of them just can’t understand it—refuse to accept it. South Carolinian Grace Ellmore wrote in her diary:

“I am trying to work out the meaning of this horrible fact, to find truth at the bottom of this impenetrable darkness…Has God forsaken us?”

And it’s not just the ones left behind who have anxious questions about what happens in death. Soldiers are, understandably, fairly preoccupied with the afterlife. As The Banner of Light, a popular Spiritualist newspaper, put it: “He desires to know what will become of himself after he has lost his body. Shall he continue to exist?—and, if so, in what condition?” Scores of books are published on the subject of heaven: there are songs and poems about it, all trying to paint it as a place that is both beautiful and not all that far from our own. Soldiers worried about their amputated limbs, as well: could they go to heaven with partial bodies? When hardcore Confederate hero Stonewall Jackson’s arm is severed and left behind him, some people actually give it a Christian burial out of anxiety over it.

It’s no surprise, then, that Spiritualism sees its highest peak during the Civil War years.

It was a sensation before – a curiosity. In 1850, Spiritualism had about two million followers. In 1862, it has tripled. The Banner of Lights starts a Messages column, where spiritualists commune with the departed spirits of soldiers and write down their messages for family and friends. Want ads from the dead…oh my. Scores of spirit circles pop up in every city, dedicated to trying to reach lost loved ones. In 1863, one such circle in New Orleans had a conversation with Andre Cailloux, one of the first African American soldiers to die for the Union. “They thought they had killed me,” his spirit said. “but they made me live.” Imagine how these words would have affected his compatriots, while the war for freedom continued to rage.“It will be I who receive you into our world if you die in the struggle, so fight!”

It’s telling that the second most popular novel of the 19th century, after Uncle Tom’s Cabin, is The Gates Ajar: an epistolary-style book about grief, loss, and the afterlife. It’s written by Elizabeth Stuart Phelps, who lost her love at the battle of Antietam. She wrote it to ease her own grief, but also for “the helpless, outnumbering, un-consulted women; they whom war trampled down, without a choice or protest.”

Like Spiritualism, it paints a picture of a beautiful heaven, just beyond the veil—one where loved ones remain who they were in life, and where families will one day be reunited.

The funeral of Andre Cailloux, the first african american soldier to die for the union. his spirit later rose from the dead to tell his followers to keep on fighting.

Wikicommons

First Lady Mary Todd Lincoln is one of many 19th-century sufferers who turns to spiritualists to ease her pain.

In 1862, her young son Willie contracts a fever and dies in the White House. Heartbroken and inconsolable, she invites several mediums to call to spirits in the White House Red Room. Abe Lincoln even supposedly arranged one, at which he peppered the medium and his spirit guides with several pressing political questions. Years later, medium Nettie Colburn Maynard wrote that she was asked to the White House by Mary Lincoln to try and ease some of the burdens sitting on her husband’s shoulders. She said she and her spirits talked to Abe for an hour, assuring him that if he went through with the whole Emancipation Proclamation, it would be the thing he’d be remembered for forevermore. It certainly sounds like something a radical spiritualist would say.

“My child, you possess a very singular gift,” Abe supposedly said, “…but that it is of God, I have no doubt. I thank you for coming here tonight. It is more important than perhaps anyone present can understand.”

It’s hard to say if this whole encounter ever happened. But who knows: maybe ghosts helped nudge Abe over the line on ending slavery!

Like Jane Pierce, First Lady before her, these seances seem to give Mary Lincoln solace. After one such seance, Mary wrote to her sister:

“He comes to me every night and stands at the foot of my bed with the same, sweet adorable smile he has always had.”

Years later, Mary takes her interest in talking with the dead even further. In the 1870s, she secretly seeks out the services of Maggie Fox to try and commune with her dead husband. The papers found her out, with the Times reporting, “the spirit of her lamented husband appeared and, by unmistakable manifestations, revealed to all present the identity of Mrs. Lincoln, which she had attempted to keep secret.”

She’s one of many people to pose for the “spirit photographer” William Mumler. He first discovers spirit photography by accident, in the 1860s, when he develops a photo and finds a “a girl made of light” – his deceased cousin. Suddenly he finds himself surrounded by spiritualists wanting to use photography as a means of discovering their lost loves ones. By the late 1860s, he’d been embroiled in quite public fraud accusations, but Mary goes to see him anyway. He uses his technological wizardry to produce a picture of Mary with her husband’s ghost.

Mary Lincoln and the spirit of abe lincoln. bizarre, to be sure, but it gave her comfort to see him watching over her.

People call her crazy, but she’s just one of many women who turn to spiritualists after the Civil War to try and find comfort. She lost several of her children and watched her husband shot right in front of her. If that’s not a reason to want to believe in spirits, then I don’t know what is. “A very slight veil separates us from the loved and lost,” she said. “…though unseen by us, they are very near.”

EXPOSED

From the beginning, for every hand that flies up in favor of spiritualism there is another trying to prove it is all a bunch of hogwash. In 1850, just two years after the Fox sisters first experiences with rapping, Congress calls for an investigation of spiritualism. It never passes – by that point, the horse is too far out of the gate.

Later in the century, with the rise of magicians, guys like Houdini make it their business to debunk the spiritualists who are giving a bad name to magic. And so does a woman called the Queen of Magic, Adelaide Herrmann. Yes, that’s right: a very successful lady magician. One of her most famous tricks is called the bullet catch, where people say she catches six bullets fired on her by local militia men. She knows that most mediums are really magicians of a sort: practicing illusions, just like she is. And she thinks it’s unethical to pretend that it’s real.

“Exposures are of frequent occurrence, many of them highly sensational in character,” wrote the New York Times in 1909. “Slate writing, spirit pictures, table tipping, rapping, and other features of Spiritualism have been exposed time and again. The exposures mount into the hundreds.”

In 1888, some 40 years after she first helped found the Spiritualist movement, Maggie Fox will finally admit that their tricks were a hoax. Maggie said..

“My sister Katie and myself were very young children when this horrible deception began. At night when we went to bed, we used to tie an apple on a string and move the string up and down, causing the apple to bump on the floor, or we would drop the apple on the floor, making a strange noise every time it would rebound. A great many people when they hear the rapping imagine at once that the spirits are touching them. It is a very common delusion.”

Her confession send shock waves through the still millions-strong spiritualist movement. According to the Chicago Tribune, those audience members “almost frothed at the mouth with rage.”

Later, Maggie will try and take it all back: a spirit made her say it was all a hoax! Naturally. It turns out that a life of being a famous child actor medium doesn’t leave you with a lot of other career options. Kate and Maggie both died lonely, broke, and as heavy drinkers.

But even after their deaths in the 1890s, there are those who still want to believe them.

The Boston Globe reports that: “The skeleton of the man who first caused the rappings heard by the Fox Sisters in 1848 has been found between the walls of the house occupied by the sisters, and clears them from the only shadow of doubt held concerning their sincerity in the discovery of spirit communication.”

The truth is that, in the 19th-century and beyond it, we want to believe. We want magic. We want to believe we can talk to those we’ve lost. And fake or not, a lot of these mediums believed they were giving people comfort – and did so. “Tell the Fox family I bless them,” wrote an ailing Horace Greeley, newspaperman. “I have been made happy through them. They have prepared me for this hour.”

Female mediums claimed a kind of power and influence that in itself was almost like magic. They paved the path for women’s rights and female speakers. They took the century’s notions of womanhood and turned them into tools to claim independence and power. Spiritualism was more than just parlor tricks and entertainment. It offered solace, and gave women a new kind of voice in America. So next time you get out your Ouija board, give them a shout.

Until next time.

VOICES

Abe Lincoln = Andrew Goldman

Elisha Kent Kane = John Armstrong

Mean newspapermen = Phil Chevalier

Horace Greeley = Paul Gablonski

Rapt audience member = Avery Downing

MUSIC

(all music used is under a creative commons license)

“Floating Through Time,” by Jeris.

Vivaldi’s Four Seasons: “Winter Mvt. 3 Allegro,” performed by John Harrison with the Wichita State University Chamber Players.

All other music is from Audioblocks.com