Dangerous Liaisons: Lady Spies of the American Civil War

If you’re a 19th-century American man, there are a few things you can be sure of.

That well-bred women are generally sweet, moral, have a delicate constitution, and would never lie to you – well, not on purpose. At least not about anything of any import. They aren’t smart enough, or devious enough, to make successful spies.

But it was these perceptions of a woman’s place that made them so perfect for the job. During the Civil War, women flirted, cajoled, and inspired men to mansplain away top-secret information. They deceived with the best of them, binding secrets up in their hair and sewing them into dresses. They wielded the sexist and racist notions that hemmed them in like a weapon, manipulating other people’s prejudice to do things that no man could have pulled off.

A lot of women spied, and for a myriad of reasons – but we’re going to walk with four of them, following their exploits through the course of the war. We’ll meet a Southern society belle in Washington who seduced secrets out of important men and was arrested, famously, for her trouble; a Union woman in the heart of Confederate capital of Richmond who ran a successful spy ring and became one of the Union’s secret weapons in that city’s downfall. We’ll meet an African American woman who infiltrated the Confederate White House, pretending to be enslaved and illiterate while she memorized war orders on Jeff Davis’ desk, and the brazen Southern teenager who used every trick in her feminine arsenal to make Stonewall Jackson her BFF. These women defied expectations, and courted serious danger, to serve the cause they believed in - one of them even died for it. It's about to get wild.

Grab your cipher, your sturdiest crinoline, and your disappearing ink. Let’s go travelling.

Suggested reading

Liar, Temptress, Soldier, Spy: Four Women Undercover in the Civil War by Karen Abbott. This book is a really delightful, immersive journey into what these spies - and Sarah Emma Edmonds - did during the war in the realm of espionage. While the author takes some liberties in terms of projecting feelings onto her characters, the book reads like a novel (in the best of ways), inviting you into their world. I loved it.

books

Stealing Secrets, H. Donald Winkler, Cumberland House, 2010.

Wild Rose: Rose O'Neale Greenhow, Civil War Spy. Ann Blackman, Random House, 2005.

My Imprisonment and the First Year of Abolition Rule in Washington. Rose Greenhow, 1863.

A Diary from Dixie. Mary Boykin Chesnut, ed. by Isabella D. Martin and Myrta Lockett Avary. New York: D. Appleton and Company 1905.

online

“Nancy Morgan Hart.” National Women’s History Museum.

“Nancy Hart Morgan.” New Georgia Encyclopedia, History & Archaeology, Revolution & Early Republic, 1775-1800.

“Kate Warne.” The Clara Barton Museum blog.

“Kate Warne” and “Women and Civil War Prisons.” Civil War Women blog.

“The Civil War and early submarine warfare, 1863” by David M. Stauffer, The Gilder Lehrman Institute.

“Civil War Spies.” The History Channel.

“Mary Richards Bowser.” The Encyclopedia of Virginia.

“The Woman Who Spied on Confederates In Jefferson Davis’ Own Home” by Erin Blakemore, TIME, 2016.

“A Very Brutal Man”: Lewis Horton, David Todd, and Prisoner Torture,” Sarah Johnson, Gettysburg Compiler 2013.

Seized Correspondence of Rose O'Neal Greenhow, National Archives and Records Administration.

“The Drones of the Civil War” by Richard Holmes, Slate, 2013.

“Women Soldiers, Spies, and Vivandieres: Articles from Civil War Newspapers” by Vicki Betts. University of Texas at Tyler, University of Texas 2016.

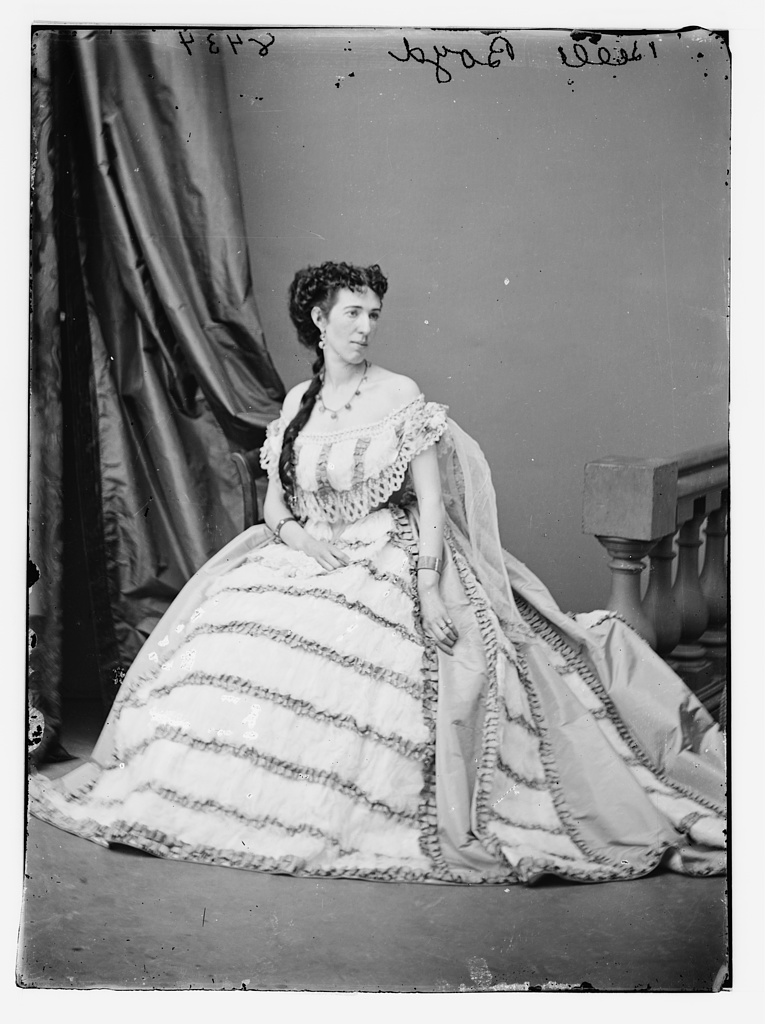

How rude! But it turns out that men had good reason to search under a woman’s skirt. Not that they did very often, which is how many a lady spy smuggled contraband.

Courtesy of the Library of Congress.

episode transcript

keep in mind that this is only a rough draft: it won’t match the final product exactly, and there are bound to be some spelling errors. my B.

Here we are again, back in 1861. But wait: before we get to spying, let’s talk about where are we with the technology in the 19th century. The spying trade goes back to the very founding of America, way back to the Revolutionary War. First president George Washington was, in fact, a real spy enthusiast. He operated something called The Culper Ring, which was hugely successful in helping America win their independence. They used codes, aliases, and secret signals that included color-coded laundry. They even used invisible ink in important correspondence, called a “sympathetic stain”, written between the lines of benign-seeming letters.

Some ladies even joined in on the fun. In 1778, a gal named Nancy Morgan Hart disguised herself as a mentally disturbed gentleman in Georgia so she could get information about British defenses there. When a bunch of British soldiers came by her house looking for someone, killed her last turkey and told her to cook it, she got them drunk on corn liquor, smuggled their guns out through a hole in the wall to her daughter outside, and shot at them until they surrendered. She later watched them hung from a nearby tree. That’s cold, Nancy.

But by the 1850s, there hadn’t been much by way of spying innovation - there hadn’t been much need for it. But there was one business bent on doing some spying and making money at it, too - that was Pinkerton’s National Detective Agency. It was founded in the 1850s in Chicago by Scotsman Allen J. Pinkerton, who became quite famous for solving a series of high profile train robberies. His organization will go on to become some of the earliest members of the secret service. In fact, they’ll save Abe Lincoln’s life.

But let’s go back to 1856 for a minute, when someone unexpected walked into the Pinkerton Office. Kate Warne, age 23, was looking for a job. A secretarial job, Mr. Pinkerton asked her? No: she wanted to be a detective. But there ARE no female detectives, he argued! And that was true: no police force will hire a woman until the 1890s, and the term “policewoman” won’t show up until the 1920s. But Kate was persuasive: she argued that women could ferret out secrets in places that men just couldn’t. They could make friends with criminals’ wives and mothers; they could charm gentleman into spilling secrets, too, and they had an excellent eye for detail. He was so impressed with her speech that he hired her on the spot, and she became - you guessed it - a bomb detective: America’s first lady private eye. It’s Pinkerton’s logo - a big eye, and the slogan ‘we never sleep’ - that helped cement that term. Except now we’re picturing Kate Warne in that trenchcoat.

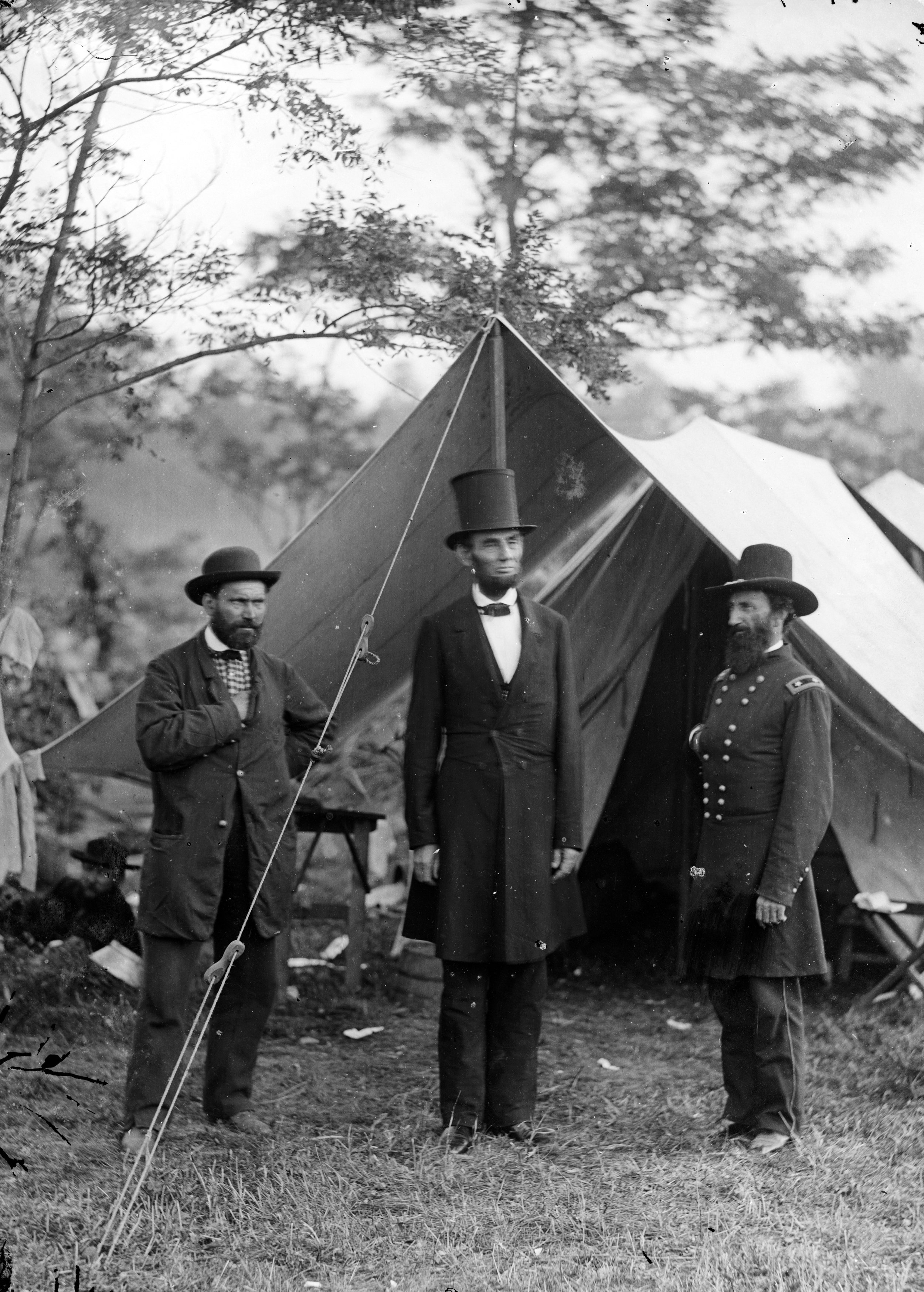

She was probably not wearing such a coat in 1861, when she played a key role in foiling an attempted assassination attempt on president-elect Abraham Lincoln by infiltrating a group of sympathetic Confederates in Baltimore, Maryland. By the year we’re in, 1860, Pinkerton had hired more ladies, whom he calls his Female Detective Bureau. They were all trained under Kate’s supervision.

But at the beginning of the Civil War, spying has, if anything, gone backward in sophistication. Though people have ideas about how to go about it. A man named Thaddeus Lowe raced to prove to Abe Lincoln that his new-fangled hydrogen balloon would be a great spying resource: he soared up above Washington, armed with a telegraph key and a Morse code operator in his basket, to prove that he could see the far away enemy and telegraph their positions to those waiting down below without being seen. Our friend Sarah Emma Edmonds was VERY impressed the first time she saw this balloon in action!

This war will produce a number of unfortunate innovations: the machine gun, repeater rifles, and trench warfare. But the most celebrated is the submarine, developed in the South to try and break the blockades the Federals set up around their ports. Allen Pinkerton, wise man that he is, actually sends one of his female spies, down there to try and find out about this new contraption. Side note: it’s because of Elizabeth Baker’s excellent spying that the Union learned how to stop their torpedoes. She sunk their brilliant invention, literally.

Something to keep in mind as we travel: the main modes of transporting any information at this point are by telegraph, train, steamer, horse, cart, or on foot. Most information needs to be delivered by hand, which means that someone has to find a way to get through picket lines, and hostile country, to deliver them.

Pinkerton and others get involved, officially, in spying for the military during the war, but much of the spying is done by civilians--people who take it upon themselves to smuggle supplies and information; who hide generals and escaped prisoners; who seduce and trick the enemy, often at great risk to themselves.

Let’s start in the nation’s capital in 1861, where a woman named Rose O’Neal Greenhow doesn’t like how the political tide is turning. Rose has lived in the city for several decades, turning herself into one of its most fabulous and influential socialites.

But before that, Rose grew up in Maryland, which at this time is still very southern, on a farm that relied in part on slaves for its labor. She lived with a few sisters, a delicate mother, and a rake of a father who seems to have been absent a lot, mostly because he liked to go out on benders.

He often took his ‘favorite’ slave Jacob on these benders at the local pub. One night, after having gotten Jacob drunk, the two of them stumbled home, but Rose’s dad fell into a ditch and hit his head. Jacob ran home for help, where an enslaved woman told him he’d better go back and finish him off, or else he’d cop the blame - which, sadly, was probably true. So Jacob went back and hit him over the head with a rock. Jacob was, in fact, held responsible - he was hung six months later. Honestly. Poor Jacob.

So Rose grew up in the shadow of that darkness and its consequences - this was the end of life as she had known it. Her mother tried to hold onto the farm, but was left with very little money and five children to care for. Eventually she had to sell it, and Rose was separated from all but one of her siblings, sent away to live with an aunt in a Washington boarding house. Maybe that’s why Rose became a staunch and unforgiving Confederate. Regardless, you’re not going to like her beliefs about slavery. But her life, her daring, and her adventures are worth diving into all the same.

Rose didn’t get a lot of schooling in her boardinghouse days, but the place still offered her a pretty valuable education. In those days, most politicians didn’t live in the city, but rather came into town for the congressional season and stayed in boarding houses like this one. This one was full of prominent Democratic senators - We’re talking big players of the day. It’s worth pointing out that what we think of as Republican and Democrat were just about flipped at this time; Republicans were way more liberal leaning, while the Democrats were all about states right and, unfortunately, most of them were pro-slavery. Rose idolized these men, who really shaped her views. She went to parties with Jefferson Davis, future Confederate president, and became close with several men who would one day become president.

Rose learned how to read their body language, to ferret out their weaknesses and doubts, and learned the political ways of the city from their daily back-door deals and maneuvering. She learned how to wield words like weapons, and to be very careful and precise with her speech. She put on fancy bonnets and took carriage rides down to the Senate, where she’d listen to these men make their cases.

In this way, she became much admired and courted by men from both sides of the political aisle. And lucky for this smart, witty, beautiful and VERY opinionated lady, her knack for witty banter and keen interest in politics were qualities generally admired by the men in Washington, unlike elsewhere.

So it was that she married Robert Greenhow in 1835, a physician, scholar, high-ranking official of the State Department, and extremely eligible bachelor, despite the fact that she didn’t come with much wealth. By the late 1850s, just before the war, she had lost her husband in a tragic accident and several of her children to illness, and though she had fallen on harder times since Robert died, was one of the best connected socialite widows in town. Perhaps, gossips said, well-connected to several prominent men’s gentleman parts. Rose was a good looking lady who continued to have many admirers, who would come over to her house often quite late in the evening. Like president James Buchanan, who raised many an eyebrow when he showed up at her house and stayed past midnight.

Men came and went, and the rumor mill churned out stories about her backdoor dalliances - hence her charming nickname, Wild Rose. She was a beautiful woman - after going to a ball in 1858, which was one of the most lavish of the decade, The New York Times described her as “glorious as a diamond richly set.” She was also a confident woman - one that seemed to exude a kind of sensuality that men, single or married, young or old - seemed to struggle not to respond to. As Confederate naval secretary Stephen Mallory will say of her later, “she was a clever woman...she started early in life into the great world, and found in it many wild beasts; but only one to which she devoted special pursuit, and thereafter she hunted man with that resistless zeal and unfailing instinct...she had a shaft in her quiver for every defense which game might attempt and to which he was sure to succumb.” But such charms don’t always impress other ladies. Mary Chestnut, our lovely southern diarist friend, said of Rose: “She has all her life been for sale.”

At the beginning of the war, Rose in not in a happy place. One of her daughters has just died of typhoid fever - the fifth of her eight children she’d lose. And she’s pissed about Abe Lincoln’s election and what she sees the north trying to do to the south. She’s making no attempt to hide her feelings. While many southern sympathizers leave the city in 1861, she’s decided to stay and see what she can do for the Confederacy. She’s in the seat of power, where all of the big decisions are being made. She has access to power and secrets. She just has to figure out how to find them.

These many assets eventually bring Captain Thomas Jordan to her door, who has decided to switch over to the Confederate side. He wants her to create and maintain a spy ring in Washington. He gives her a cipher full of mysterious symbols and teaches her how to make Morse code with her curtains. She can signal to a watching picket that way, or by doing the same thing on the street with one of her fancy fans.

Understand that D.C. is a place of mixed allegiances. Before the war, it was a southern-leaning city, with deeply southern Virginia on one side and Maryland on the other. It’s the seat of the Union, while also being no more than 200 miles from the Confederate capital of Richmond. So really, it’s the perfect place for a well-connected spy lady to be. Rose doesn’t find it hard to find recruits for her ring. Fellow ladies and their daughters, for example.

Let’s say that we are eager lady spies, called to Rose’s house for duty. She wants us to carry some letters through the capitol, past camps full of soldiers and through several picket lines, all without an official pass to do so. Um...and how are we supposed to do that? Well: to begin with, look down. That’s where you will find the lady spy’s hiding places of choice.

Let’s start with your hoop skirt. Remember that giant birdcage under your petticoats, strapped around your waist - your crinoline? Its steel bands are perfect for tying things onto, and their balooney circumference means they can dangle down around your sensitive region without ever showing through. And not just a few things - many things. You’d be amazed how much stuff you can hide under a crinoline. One woman managed to get a bolt of cloth, several pairs of boots, sewing silk, and some packages of gilt braid under hers in one outing. One Kentucky girl made the papers for managing to smuggle 200 Colt revolvers through the lines under her hoop skirt. Yes, that’s right: guns dangling down around that brave gal’s lady parts.

How many guns did one Kentucky girl smuggle under her skirts? 200 over the course of two weeks. A 19th-century woman’s cumbersome clothing was often her best spying accessory.

Courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

One hopes they weren’t loaded, am I right? Comin’ in hot!

But that’s not all. You also have your corset and many layers of petticoats, and you can sew things into its voluminous folds. In this age that is so conscious of respecting a lady, how likely do you think it is some guard will want to stick his hand in there? The answer is: Extremely unlikely. Even if he suspects you’re carrying more than you should, he’s probably too embarrassed to say so.

With the first major battle of the war looming, Rose continues to court many admirers, from generals to their lowliest secretaries, in order to squeeze information out of them. And she is really VERY good at it. Colonel Erasmus Darwin Keyes, military secretary to the Union’s commanding general at the time, Winfield Scott, said she was “one of the most persuasive women that was ever known in Washington.”

And then there’s Massachusetts senator Henry D. Wilson, chairman of the Committee on Military Affairs. He supposedly wrote Rose 13 spicy love letters and signed them simply ‘H’. though I don’t know that I’d find them very titillating…he mostly writes about his indigestion. Or how longing for Rose gives him indigestion. Mmmm.

Or at least that’s who Rose tried to pin the letters to when they were eventually discovered at her house by investigators. We don’t know why Rose didn’t burn the letters, or if Henry ever told her anything important, but they show that Rose was keeping regular steamy correspondence with high-ranking Union officials. And maybe enjoying more than words on paper.

So when she learns the date when the Union army plans to move, she calls Bettie Duvall, aged 16, to her house, and promptly goes about outfitting her as a farm girl. Her calico dress is plain, but she has a fancy secret: a small black silk purse hidden in her hairdo. The message in the purse is simple, written in cipher: “McDowell has certainly been ordered to advance on the 16th. ROG.” But in the right hands, it might help win the first battle of the war.

Bettie rides a horse cart through Georgetown, past long rows of Union tents and across the guarded Chain Bridge. And somehow, no one stops her. Maybe it’s too early in the war for them to worry much about checking passes. Or maybe it’s that she’s just...a woman. She arrives the next day in Vienna, VA, where she asks a brigadier to deliver her message to General Beauregard. He was quite charmed by this “...brunette with sparkling brown eyes, perfect features, the glow of patriotic devotion burning in her face.” And then when he asked to see the message, she let her hair down - literally - and he stood there, entranced, as out tumbled that fine little purse.

And so it is that a woman helped the Confederacy win the First Battle of the war. Overnight, Rose becomes a sensation. And even as rumors of her deeds start to spread - publicity ain’t a good thing for a spy - she seems to think she’s untouchable. She continues to have her spy ring over for sewing parties, at which she talks shit about Lincoln and outlines new and ever-more daring feats.

MEANWHILE, DOWN IN VIRGINIA, we have two very different ladies, fighting on opposite sides of the line.

In Martinsburg, 17-year-old Belle Maria Isabella Boyd is chomping at the bit to aid the Southern cause. This teenager, who will go on to be known, fabulously, as the ‘Secesh Cleopatra’, comes from a wealthy Virginia family. Several of Belle’s family members join up to fight in the Confederacy - uncles, cousins, even her father - but the area actually voted against secession.

You’d think that perhaps she would have tried to fight with them, but Belle is too much of a flirt to become a secret soldier. However she is a fan of brazenly waving at soldiers, as well as organizing morale-boosting trips to local army barracks. Belle likes attention: the more the better. Which might be why a rival in Martinsburg called her “The fastest girl in Virginia, or anywhere else…”

She may not, like Rose, be the most beautiful woman in a room, but her confidence and brazen charm knock the wind out of many.

“I am tall. I weigh 106 1/2 pounds. My eyes are of a dark blue and so expressive. Nose quite as large as ever, neither Grecian nor Roman, but beautifully shaped...and indeed I am decidedly the most beautiful of all your cousins.”

And she isn’t the only person to admire her personal charms. Her special something prompted a friend of author Charles Dickens to call her ‘disturbingly attractive’ with a face that suggested “joyous recklessness.” Joyous recklessness about sums Belle up, I’d say. She is quick, precocious, and as her mother likes to say, ‘very saucy’. When she was 11, she rode her horse into a dinner party after being told she wasn’t old enough to attend. When her mother gave her the ultimate death stare, she quipped, “my horse is old enough, isn’t he?”

Her maid - which is the genteel Southern word for ‘slave’, by the way - is called Mauma Eliza, and she has been with her since birth. Belle taught her to read and write in secret, though it was illegal. She still supports the Southern cause, but isn’t like Rose, who thinks slavery is just fine the way it is forever. “Slavery, like all other forms of imperfect society, will have its day,” she wrote, reflecting the thoughts of many other Southern women. “But the time for its final extinction in the Confederate States of America has not yet arrived.” So yeah, still not great, but it is what it is.

But this isn’t an easy place to be a fervent rebel. Boys from Martinsburg are joining up for both the Union and the Confederacy, which goes to show that there’s a lot of truth behind the idea that this war is truly ‘brother against brother.’ The town is so close to Washington that it keeps changing hands, being taken over by different sides. The papers warn of the terrible fates that will befall women whose towns are taken by Yankees: theft, arson, rape. And as we talked about in episode four, this isn’t a completely crazy notion. And there are so few men left behind to defend a lady’s honor.

So imagine hearing the shouts and gun shots of the enemy outside your window, watching them looting, drinking and burning their way to your front door. In July of 1861, that’s what happens to Belle. As she put it, “On they came...with all the pomp and circumstance of glorious war...the doors of our houses were dashed in; our rooms were forcibly entered by soldiers who might literally be termed ‘mad drunk.”’ A bunch of Union soldiers crashes their way into her house, and demands to know where their Confederate flags are hiding, to which her mother asks that they leave. As arguments rage, one of them steps forward menacingly, and Belle starts to suspect that one of them is setting to commit a “Yankee outrage” on her mother. “I could stand it no longer,” she said. “My blood was literally boiling in my veins.” So she grabs a pistol, and when he advances on her, she shoots him dead. His angry fellow soldiers quickly gather around, raising their guns, and so what does she do? She spreads out her arms and says: “Only those who are cowards shoot women. Now shoot!”

And what happens to Belle, after she kills this officer in front of many witnesses? She is questioned, and then she’s pardoned. The Union even puts some guards around her house for protection. At this point, no one in the Union is keen to punish women as war criminals. They don’t really think them capable of being ones. And so off the budding spy went, on to more ambitious, and dangerous, deeds.

MEANWHILE, almost 200 miles away in the heart of the Confederacy, is Elizabeth Van Lew. Her family is originally from the north, but made their fortune in Richmond, Virginia. Her father’s business was one that Thomas Jefferson and his new university, UVA, spent money in; enough money that the Van Lews bought an elegant mansion right in the heart of town. But her family were never considered true Richmonders. Despite their money and their good address, where they threw lavish parties for presidents and poets like Edgar Allen Poe, they were never quite considered ‘one of us’. One of the reasons was because of the Van Lew ladies’ attitude toward slavery. “It was my sad privilege to differ in many things from the perceived opinions and principles in my locality,” she said. “This has made my life intensely sad and earnest.” When Elizabeth’s father died, he left their 15 slaves to his wife, stating that she wasn’t to free them. So she and Elizabeth took it in legal baby steps, letting them to go out and do freelance work for a small sum so they could all eventually buy their freedom. Many of them stayed and worked for these ladies even when they were free - the word “servant”, in her house, wasn’t a euphemism. Elizabeth also spent chunks of her $10,000 inheritance to buy slaves just so she could free them.

“Slavery is arrogant. It is jealous and intrusive - is cruel - is despotic - not only over the slave, but over the community, the State.”

Just like Rose, her political views aren’t exactly a secret, which makes her stick out like a very sore thumb. But by 1861, Elizabeth is in her 40s, considered a harmless, eccentric old maid. Not someone to put on the neighborhood watch list.

Obviously, she is very keen to see the Union win, but living in the Confederate capitol, it would be dangerous to openly express such a view. So every day she goes about her usual business, paying calls and nodding vaguely over tea when people talk about wanting to hang Abe Lincoln. While Rose was celebrating her win over the battle at Bull Run, Elizabeth watches quietly as local families do what was called “stirring up the animals” - yelling at and insulting the 1300-plus Union prisoners captured there and brought back to Richmond through the bars of their makeshift prisons. But at the same time, she’s also resurrecting her bygone flirting skills to try and work her way into those jails to help them out.

She goes to see David H. Todd, who happens to be Abe Lincoln’s brother in law, who is the man in charge at Libby Prison, and asks if she could serve as nurse for these soldiers. Todd, it must be said, is kind of a dick. He’ll become rather notorious for foul treatment at this prison: giving soldiers rotten food and barely any medical attention. He apparently ran one prisoner through for lighting a contraband candle to dress his own wound with. So unsurprisingly, he said he couldn’t allow it. He also added: “you are the first and only lady that has made any such application.”

Eventually, she’ll smile through her teeth, probably hoping he’d fall off a cliff ASAP, while buttering him up with some of her ginger cake. But first, she goes right on over Todd’s head, straight to one Christopher Memminger. She flatters and praises, making herself seem as unthreatening as possible. When that doesn’t work, she throws a tried-and-true Victorian woman’s hail Mary: ‘it is my Christian duty to tend to the sick, Sir’. Remember that in this America, women are paragons of virtue and morals. If she says that God wants us to let her in, then I guess we kind of have to? Good one, Lizzie.

She starts visiting the prison regularly, bringing the Union prisoners food, books, clothing - later, an amputee named Lewis Francis will say that he would have died in there if not for Lizzie and her mother.

But she also brings them messages, and the means to write her ones back. She has servants bring them eggs, which the prisoners then drain and fill with secret messages. They prick letters in the books she loans them to form messages, created with the needles she sews into the collars of donated shirts. Sneaky!

For her pains, she and her mom got a heaping pile of public censure. They even got into the paper: their names weren’t used, but everyone knows who the story was about. “I have had brave men shake their fingers in my face and say terrible things,” she said. “We had threats of being driven away, threats of fire, threats of death…surely madness was upon the people.” And it sure is upon the people of Richmond. By 1862, Richmond will be under martial law. Jeff Davis, president of the confederacy, is demanding spies are be caught and imprisoned, and the Confederate congress has passed a law that lets troops and government officials seize the property of any women suspected of being spies.

So the ladies contributed money and supplies to Confederate soldiers, trying to make a show of their patriotism. And guess what? They just kept on doing their thing for the Union. She isn’t arrested - she isn’t detained. Because really, she’s just an eccentric little lady. What harm can she really do?

Turns out, quite a lot.

Back in D.C., Rose Greenhow is still spying with a vengeance. But she’s starting to get worried that she’s being followed. Paranoid, she spends hours at her Singer sewing machine, working secrets and things of value into her underthings, and stitching maps into her lining and cuffs. The most important letters go behind the laces of her corset

And she’s right: she is being watched by famed detective Allen Pinkerton. He and his agents stalk her, under cover, following her to markets and parlors, and staking out her house. But that doesn’t stop Rose from carrying on with her activities, seducing information out of the men around her and passing them on to the Confederates across the Potomac: she even openly talks shit about the Union army in the Senate gallery. When a man interrupts her to say her words are treason, she gives him a serve about how rude he is to be butting in her conversation. Rose is good at finding ways of making men feel like idiots.

Finally, on August 23, 1861, Pinkerton makes his move. But Rose is warned, during a walk home, that there were people guarding her house, so she had at least a few minutes of scheming to do. She took a note out of her pocket, swallowed it, and walked regally up the stairs to her house. When Pinkerton meets her at the front stoops and says he’s come to arrest her, she characteristically demanded to see his warrant.

“I have no power to resist you, but had I been inside of my house, I would have killed one of you before I submitted to this illegal process.”

Damn, Rose.

They hoped for a nice, quiet, leisurely search through her house, but Rose’s cherished eight-year-old daughter, little Rose, ran out into the yard screaming ‘Mother has been arrested!!!” So they get busy real quick, before a crowd can gather. And this is what really showcases the fact that she’s not a trained spy - she’s left stuff EVERYWHERE. They find notes on military preparations full of things that she really has no right to know. But in the madness, Rose is able to get rid of a lot of information. She tucked notes in new hiding places while the detectives weren’t looking; she even managed to get up to her bedroom, saying she needed to change, and destroyed a few important papers, including the cipher she used for all her correspondence. But mostly, she is confined to her parlor. “Although agonizing anxieties filled my soul, I was apparently careless and sarcastic and, I know, tantalizing in the extreme.”

And so they are put under lock and key, arresting anyone who showed up at her door.

The triumphant officers broke out her finest brandy and started bragging about all of the ‘fine times’ they were going to have with the lady prisoners, and Rose realizes what a heaping pile of trouble she’s in. “My castle,” she wrote, “has become my prison.” And so it was that her house was renamed The House of Detention for Female Rebels – but the press dubbed it ‘Fort Greenhow’.

At first, she’s able to charm a few officers into giving her some time alone, during which she destroys all remaining evidence. But as her weeks of house arrest go on, she comes to realize “the dark and gloomy perils that environed me.” The men try to get her to confess to what she’s done by threat and degradation. They never let her dress or sleep with the doors closed. They dangled her lady friends in front of her, keeping them under house arrest in the same house, but won’t let Rose see them. But even with all this, the ever-resourceful Rose manages to keep on spying. She sent benign-sounding letters to friends, filled with secret messages. She uses balls of yarn to weave color-coded tapestries. She even got Little Rose, who was allowed to play outside, to pass messages to and from agents on the other side of the fence. Even as the guards continue to isolate her, decreasing her food and stepping up their interrogations, with no legal recourse and no rescue in sight, she keeps spying. When men like the secretary of state tell her she’d better cooperate, she lectures him on her American rights.

“Freedom of speech and of opinion is the birthright of Americans. You have held me, sir, to a man’s accountability, and I therefore claim the right to speak on subjects usually considered beyond a woman’s ken…”

This lady did NOT come to play.

Meanwhile, back in Martinsburg, Bell Boyd is reading all about Rose Greenhow and longing for the same kind of importance and fame. Belle isn’t always good at being discreet, but that’s all a part of her process. She’s of the mind that if she’s loud enough and central enough, no one will suspect her of being underhanded. And maybe Belle is onto something there. Most women aren’t searched when they pass through pickets lines – and those who are, if they play meek and sweet, aren’t searched hard. Of checking such women at camp borders, a Union picket said: “Some of the old and ugly ladies make a great fuss about being searched, but the young and good looking ones are a great deal more amenable.” Gross. But Belle knows how to play it. One time, when delivering a very secret message, she keeps it out in her hand, fanning her face with it. It could easily have been checked, but no one does.

She’s in a great place to do a bit of pro bono spying, right in the thick of the eastern war zone, surrounded by Union camps just begging for their secrets to be pilfered. And she’s very keen to aid the cause, whether that cause is keen on her or not. Apparently she has a real thing for Confederate commander Stonewall Jackson. Can we just talk about how weird this crush is for a minute? This guy is 40 years old, intensely religious, and because he thought one of his arms is longer than the other, he’ll often hold one up over his head to improve his circulation. He also has a thing for lemons, which he sucks at every available opportunity. So there’s that.

Belle takes to riding her horse Fleeter around the state, trying to get the Confederacy to take her seriously. She even trains him to go down on his knees on command so she can hide if Yankee soldiers pass by.

Belle’s problem is that she wants to be noticed, which is not a great attitude for a wannabe spy.

It’s hard to blend into the wallpaper when you’re walking around with a little black dog dressed in a fitted jacket, which she used to hide letters and other contraband. Do you remember the last time you saw a tiny dog in a jacket? You stopped: I’m sure of it. And your heart exploded into tiny butterflies of joy.

In her quest to be noticed, she sneaks into a Confederate camp one night, in a delightful sexy-soldier outfit that feels to me like the 19th-century equivalent of the sexy firefighter Halloween costume - selling soldiers stolen whiskey for two dollars. One of them yanks a bottle out from under her skirt, and she pulls a knife on him. Which I think is fair. But she manages to turn this situation into a fight, where 30 men are badly wounded. Whoops!

But that’s not to say she isn’t doing good things. Like many unofficial lady spies, including Rose Greenhow, she uses her womanly weeds to great and truly helpful effect.

With the North choking off the South’s supply lines as part of their strategy, vital things like quinine, postage stamps, and coffee are becoming increasingly scarce. And so the South develops their own Underground Railroad (called the Secret Line), a network of couriers stretching between Richmond and Washington that get news and supplies where they’re needed – the same line Wild Rose uses in Washington.

But Belle wants to stand out from the growing field of freelance operatives, so she starts creeping into Union camps at night, picking up lonely sabers and pistols, and hiding them off in the woods. “I had been confiscating and concealing their swords and pistols on every possible occasion,” she wrote later. “…and many an officer, looking about everywhere for the missing weapons, little dreamed who it was that had taken them.” Other girls would come along and tie these stolen goods to their crinolines.

This is one of the most popular, and successful, ways for a lady to smuggle things across the lines. But women also find other ways to hide their bounty. They cook pistol pieces into bread loaves; pack quinine into hollow doll’s heads and jars of preserves. Now that’s ingenious.

It’s no surprise that she manages to get arrested three times behind federal lines. But when she’s caught, officials don’t seem to know what to do with her; they just slap her lightly on her delicate wrist and send her home. After being taken in for questioning, and getting away with it, she wrote, “my little ‘rebel’ heart was on fire and I indulged in thoughts and plans of vengeance.” Every time they let her go, she gets bolder. It’s crazy, that the Union doesn’t try to do more to stop her. But then again, she’s just a silly 17-year old-girl, right?

Turns out that constantly underestimating the ladies is one of our very best weapons.

Meanwhile, Elizabeth Van Lew is reading glowing stories about Rose in the Richmond paper, which are all outraged at her treatment. “Nothing is so hideous in the tyranny inaugurated at Washington as its treatment of helpless women...” one story said. “None but savages and brutes make war upon the defenseless sex.” Meanwhile, Richmond gal Mary Chestnut thinks it rather marvelous to see a lady held for such a thing. She finds it “…delightful to be thought of enough consequence to be arrested!’

But Lizzie finds none of this at all delightful. There is a very Victorian double standard at play here: if Rose Greenhow was a man – or, it must be said, a person of color - she would be tried for treason, and perhaps hung. Union spy Timothy Webster was the first spy to be hung, right there in Richmond, in April of 1862. But because she’s white, female, and privileged, she’s treated like a delicate flower. That makes Lizzie mad – but hey now. Two can play at that game.

At this time, Richmond’s under martial law – several men AND women have been arrested under nothing more than a suspicion that they were sympathetic to the Union. But she kicks up her efforts at Richmond’s prisons anyway, making friends with northern-leaning guards, ferreting out other potential spies, and finding ever more ingenious ways to smuggle in money, supplies, and information. She frequently brings an antique French plate warmer to the prison, its hollow bottom filled with money and things. One day, when she overhears a guard say he’s going to inspect it next time she visits, she made sure to fill it with boiling water. When he grabs it from her, it scalds his hand!

But she isn’t just helping soldiers – she’s setting up a full-blown spy ring, recruiting railroad conductors, servants, and others who are keen to help the Union cause. Many of her agents are African Americans keen to screw the people that deny them freedom. This is a very dangerous business, most especially for the feather in Lizzie’s spy ring’s cap: Mary Jane Bowser.

When Elizabeth hears that Varina Davis, first lady of the Confederacy, needs some help in the Confederate White House, she helpfully offers her slave Mary’s services. Except, of course, that Mary isn’t a slave. Like, at all. She’s a free woman, originally Mary Jane Richards, who grew up under Elizabeth’s care – as a young girl, she was sent North to get an education and spent time abroad as a missionary in Liberia. But she was unhappy there, so Mary decided to come home to Richmond, where she was arrested in 1860 because the law didn’t recognize her freedom. All freed black persons had to leave the state of Virginia within a year, and couldn’t return, or they risked being re-enslaved. Yikes. To get her out, Elizabeth paid bail and had to say that, just kidding, she was Mary’s owner. Now it’s time to play that card again.

Mary agrees to move into the Confederate White House, acting the part of dim-witted house servant so she can gather information. Because of course this woman can’t read; I mean, the law says so. And so this woman uses their prejudice against them. She reads papers on the Confederate President’s papers when he’s away from his desk and eavesdrops on his conversations, committing them to memory. She transcribes letters and maps and then, it’s said, she smuggles them out in the first lady’s dresses! She rips open part of Varina’s waistband, sews messages into them, and then leaves them with the seamstress, who lets Elizabeth come and have a read. But Elizabeth can’t be seen swinging by the seamstress’ shop too often. So if Mary Jane has really important intel, she’ll hang a red shirt out on the laundry line to alert Lizzie that she needed to come. Elizabeth wrote of the arrangement:

“When I open my eyes in the morning, I say to the servant, ‘What news, Mary?’ and my caterer never fails!”

It must be said that, years later, Varina Davis will say that no such person ever worked in the Confederate White House, though Mary Bowser and Elizabeth Van Lew will say she did. There is really no hard evidence that she was there, and that she smuggled things out in the First Lady’s dresses. But…can we just pause and appreciate how amazing this is? I mean...YAS.

While Elizabeth is working out how to get into prisons, and to sneak men out of them, ROSE GREENHOW and Little Rose have been moved into Capitol Prison, after five months of house arrest. Which is kind of crazy, because it’s the boardinghouse Rose spent her formative years in – and in many years to come, it’ll be the spot where the Supreme Court will stand. Except it isn’t anything like what Rose remembers. Conditions are not great in the American Bastille. It’s filthy, overcrowded, and stinks to high hell. The food is terrible and scarce: greasy beans and bad bread that leave Little Rose crying at night from hunger. They aren’t allowed outside to exercise, her room dark and windows barred. Men are hung from the gallows here; given her notoriety, it wouldn’t have been out of the question for them to hang her. So, not a super nice place to spend time.

Rose spends the long nights clutching her empty pistol, trying to keep the rats at bay and using her candle to burn bedbugs off the wall. She lay on their itchy straw pallet, burning with indignation.

“To-day the dinner for myself and child consists of a bowl of beans swimming in grease, two slices of fat junk, and two slices of bread. Still, my consolation is: every dog has his day.”

Visitors pay to pass by and see them, like an exhibit. Through it all, Rose holds onto her fire. When, inevitably, Little Rose gets sick, Rose makes the questionable decision to deny the army doctor and demand her personal one – she just didn’t trust him. And it was a small act of rebellion: of regaining control and asserting her agency. In a situation where she had no idea what was going to happen to her, you’ve got to admire her for that. She finds the strength to pry a wooden floorboard up from the floor of their cell and lower her daughter down through it, into a cell full of Confederates, who share news and food. And don’t worry: our Rose is still spying.

Eventually, she’s called up in front of the Prison Commission and questioned about the scraps of paper Pinkerton had found. From beginning to end of this little inquisition, Rose manages to completely run the whole show, as imperial as any queen. Without any representation, she argues that 1) as a Southerner, she has a right to defend her cause; 2) that she’s done nothing but write letters to friends expressing her opinion; as an American citizen, isn’t she allowed that freedom of speech? 3) that it isn’t her fault if people tell her things. “If Mr. Lincoln’s friends will pour into my ear such important information, am I to be held responsible for all that?” The Scarlett O’Hara little-old-me defense with a side of carbolic acid. I like it.

Representing herself, she completely rips apart the guys who were questioning her. I can’t even tell you how much she schools these fools, who just seem incapable of really grilling a woman. So they are at a stalemate, and she goes back to prison and awaits further judgement.

What Lincoln really wants is to send her South, out of the capitol, but apparently General McClellan thnks she has too much information to let her go. And apparently she doesn’t WANT to go south: she wants to stay at home, where she can get the most intel (Yikes, girl!). But her stamina is failing, with nothing to do and a child wasting away before her eyes. “Day glides into night with nothing to mark the flight of time, and hope paints no silver lining to the clouds which hang over me…”

Eventually, she is given a choice: take the oath of allegiance and stay, or be exiled South for the duration of the war. Tired of prison, she takes the second option.

Meanwhile, in Richmond, things are getting much more dangerous for ELIZABETH AND MARY. Confederate agents are watching Lizzie closely, as are her neighbors, trying to sniff out any foul wind. But Elizabeth isn’t about to lie down and take the way Union prisoners are being treated – Rose Greenhow thinks she has it bad. Guards take any opportunity to shoot the men under their charge. “To ‘lose prisoners’ was an expression very much in vogue,” she wrote later. “And we all understood that it meant cold-blooded murder.”

Though security increased about Libby Prison, she finds ingenious ways to sneak prisoners out. She bribes guards to send prisoners to less guarded places, like hospitals, where they’re easier to get at. She sends them messages for a while in the bottom of a custard dish.

It helps that she has a friend on the inside. Erasmus Ross makes a big show of being mean to prisoners, yelling and swearing at them. Then one day, he punches William H. Lounsbury in the stomach, saying: 'you blue-bellied Yankee, come down to my office!'. He thinks that maybe he’s about to be shot. But no: Erasmus hands him a Confederate uniform and tells him how to get to Miss Van Lew's.

She has her bravest, sharpest servants, often African American, constantly hovering around the prison, waiting to receive and guide such escapees. At her house, they are put in a secret attic room tucked behind a chest of drawers, its secret door almost like one of those library rooms I’ve always wanted where you pull a book out and the whole wall turns. She gives them food, money and tells them where to go for help going North.

All of this with men always showing up at her house, trying to trip her up by pretending to be Union sympathizers. How’s she supposed to know which is an escaped prisoner in a stolen uniform and which are just jerks trying to get her caught? There’s also the fact that her also-Union-loving brother is having major trouble with his contentious, fiercely southern sister-in-law, who is currently living with them! Lizzie’s smuggling men up and down the stairs, right by that sister’s door. Yikes.

Her two little nieces are living with her too. One day they sneak up behind Lizzie to the secret room and take a peek at what’s behind it: two very smelly men, all dirt streaked. One of them smiles and says “My, what a spanking you would have if your aunt had turned around!”. The girls will go on to keep this secret from everyone, including auntie. Good little Union girls! Or maybe just afraid the stinky men would come and eat them.

It gets better. One time, she has a 15 year old agent named Josephine go to visit the prison hospital, where she gives a few of the boys there a plan: one of them will play dead; the other one will cover him up and move him to the morgue; then, during a staged fight between the other inmates, the two will sneak out the front door of the prison. And it works! Whaaaaaat? And Lizzie doesn’t feel at all bad about it. “As desperate situations sometimes require despicable remedies.”

Meanwhile, she’s recruiting new spies with a vengeance. Including the head of the Fredericksburg and Potomac Railroad, who causes Lee and his army a fair amount of delay and trouble. Her growing network write gossip on pieces of paper, tie them to flowers, and leave them on certain gravestones at St. John’s in the dead of night. Black members of the community are integral to Lizzie’s spy network, and to Union spying in Richmond in general. Men in Elizabeth’s employ go out shopping with secrets sewn into their clothing, and women tuck things into eggs and into the false bottoms of baskets. They’re all playing with fire, but no more so than the people whose freedom hung in the balance.

Lizzie organizes their efforts and fuels her agents’ courage, using her connections to bring people over to the cause. She also leads from the front, delivering secret messages herself dressed as a farmhand in buckskin leggings. Sometimes she even stuffs her cheeks with cotton balls to distort her features. But the more people she and her network help escape, the tighter security gets around the prisons and throughout the city. When Jeff Davis’ coachman runs away, it brings Mary Jane under much greater scrutiny.

She’s subject to stops from ‘impressment agents’, who steal supplies for the increasingly floundering Confederate army. They’d already taken three of her pretty carriage horses when Elizabeth brings the remaining one inside when they come around. “…our horse accepted at once his position and behaved as though he thoroughly understood matters.”

She stays calm and cool when they search her house, even though there are men up in her attic. In fact, she serves them cookies. It’s this pleasing domesticity, and her place in high society, that probably saves Elizabeth from jail.

A little further north, BELLE BOYD’s mother had sent her down to Front Royal, hoping she’ll be less in the way of the fighting there. Good luck with that, mom. She makes herself useful at her aunt’s Fishback Hotel, flirting with Union officers. The local girls sure didn’t like her much, as per usual, calling her “all surface, vain, and hollow” and “perfectly insane on the subject of men.” Crazy she might be, but she’s also crazy focused, working her supposedly silly way into many high-up Union hearts.

One Captain Keily brings her many things, among them: “some very remarkable effusions, some withered flowers, and last, not least...a great deal of very important information.”

Including information about a council of war that was happening in the hotel where she’s living. That night she creeps upstairs, climbs into a certain cupboard, and listens through a hole drilled into its bottom as the generals unveil their plans. Then she dresses up as a boy, as you do, and rides through the night to Stonewall’s cavalry commander. “Good God!” He supposedly said upon seeing her. “Miss Belle, is this you? Where did you come from? Have you been dropped from the clouds? Or am I dreaming?”

She delivered her intel and was in bed before daybreak. Belle’s much better at sneaking out than I was!

But her real claim to fame comes at the dawn of the Battle of Front Royal. As Union troops march through, readying themselves for a Confederate attack, she asks a passing soldier what’s going on. He says they’re planning to burn the bridges and the ammunition stores before the rebel army can get to them. She knows where all of the troops are, from all of her spying, and she realizes that they don’t yet have the numbers to fight off a full-on attack. The Confederates can win the day, if she helps them.

So she runs: through the town and across the fields. Yankees shoot at her back, and rebels are shooting at her front, not knowing she’s really on their side. Bullets rip at her skirts.

“I shall never run again as I ran on that, to me, memorable day. Hope, fear, the love of life, and the determination to serve my country to the last, conspired to fill my heart with more than feminine courage, and to lend preternatural strength and swiftness to my limbs....Their cheers rang in my ears for many days afterwards, and I still hear them frequently in my dreams.”

And so the Confederates rushed in and won Front Royal, handing Stonewall Jackson his first big victory. Apparently he sent her a thankful note. Although it must be said that, when she tries to visit him later, he refuses her. No matter what service she’s done, he still thinks that she was more nuisance than help. Classy, Stonewall.

At this point, she’s officially famous, with Northern reporters calling her “an accomplished prostitute who had figured largely in the Rebel cause.” But that doesn’t stop her from spying up a storm. But eventually one of her beaus sets a trap for her and she’s caught, AGAIN. But this time she’s arrested: she gets sent up to our old friend, Old Capitol Prison, plunked into Rose Greenhow’s old cell.

While in jail, she makes herself as annoying as possible. Local admirers keep her stocked with chicken, soup and beefsteak, as well as newspapers, gratifyingly filled with her name. One story about her is titled: “The Secesh Cleopatra is Caged At Last!” She calls her guards names and sings loud, Confederate songs. And she flirts, of course: a girl’s gotta pass the time, you know? She passes notes with a dashing prisoner across the prison aisle. Until one of the guards skewers her arm a little with his bayonet. That wound will leave her with a scar, though, which she thinks is kind of cool.

After just a month, she is exchanged for Union prisoners – sent right back down South. It seems like the government is more keen on getting her out of their faces than on taking her seriously. Lucky for Belle.

Back in Richmond, she meets her idol: Rose Greenhow. They go around to hospitals together, caring for the wounded and telling them stories all about their daring do.

In Richmond, ROSE is hailed as a hero. Even President Davis goes to see her, praising her iron will and service and offering her a couple thousand dollars as thanks. But still the stuffy Richmond ladies are hesitant to accept her, with so many tales of her late-night callers. So when Davis asks her to sail over to Europe and drum up support for the Cause. She would be one of the only women – if not THE only one – sent overseas as an emissary. And of course, she doesn’t hesitate.

But to get there, Rose and her daughter have to run the blockade: essentially, they have to take a stealth ship, sneaking through a Union blockage by night, which is a very dangerous business. The Confederate gives her more than 500 bales of cotton as payment, which is going for a very pretty price overseas.

She goes to London first, where people say nice things but aren’t very helpful, as they’ve already abolished slavery and all; and then to Paris, where she meets up with Napoleon III in the Tuileries Palace. Yes that’s right: an American woman, holding court on her own with a Napoleon, asking him for aid. Damn.

Running the blockade around Confederate ports wasn’t easy, and it was dangerous. Ships had to run at night, all lights out.

Courtesy The Jay T. Last Collection of Graphic Arts and Social History, Huntington Digital Library.

He’s sympathetic, but essentially says ‘ya, that would be great, ma cherie, but England will need to go along”. Which they won’t. She spends months going to parties, talking shop, maybe scoring some amorous conquests, and writing her memoir, which the New York Times calls “as bitter as a woman’s hate can make it.” In the end, she gets sick and tired of everybody’s bullshit. The south is losing, and she wants to go home. “The desperate struggle in which my people are engaged is ever present,” she wrote. “I long to be near to share in the triumph or be buried under the ruins.” She put a tearful Little Rose into a school in Paris for safekeeping and gets ready to sail.

The stealth ship she takes back to America, called the Condor, makes it to the coast of Wilmington, North Carolina, in the dead of night. It’s hard to see anything, without a lot of light to guide them. So when some Union blockade hunters opened fire, the captain swerved to hit what he thinks is a Union ship and runs aground on the wreck of another blockade runner. Panicked and completely unwilling to be taken prisoner ever again, Rose demands to be given a lifeboat to get to shore. And so off she goes, into dark and choppy waters, in a heavy black silk dress and a leather satchel containing letters for Richmond and $2,000 of heavy gold coins around her neck. And so it was that, when the boat capsized just 300 yards from shore, Rose Greenhow drowned. The next morning, a ship captain found her body on the beach, looking calm and still regal. She was honored with a full military burial.

“At the last day, when the martyrs who have with their blood sealed their devotions to liberty shall stand together…” the local paper said, “…foremost among the throng, equal with the Rolands and Joan d’Arcs of history, will appear the Confederate heroine Rose Greenhow.” But let’s end her story with Rose’s own words, from a note found on her body meant for her daughter Little Rose:

“You have shared the hardships and indignity of my prison life, my darling; and suffered all that evil which a vulgar despotism could inflict. Let the memory of that period never pass from your mind; Else you may be inclined to forget how merciful Providence has been in seizing us from such a people.”

Think what you want about Rose Greenhow. But she was smart, principled, fierce, and knew how to fully commit to her cause. And in the end, she died for it.

Still in the South, Belle had been arrested AGAIN when she went home to Martinsburg to see her ailing father. It was technically Union territory, and she’d promised to stay in the South for the duration of the war. And that’s how she lands herself in Washington again. She spends some of her incarceration blowing kisses to her guard, one Lyons Wakeman. Remember her? Little does Belle know she’s flirting with a lady soldier: though I don’t think that knowledge would have changed a thing.

When she’s finally exchanged again, she can’t go home to see her family – so what to do? She decides to follow Rose Greenhow’s example and go to Europe to fight for the cause. With $500 in gold from the confederate government and letters of introduction in her pocket, she boards the ship Greyhound and sets off. She holds her breath as it glides through the black water, all lights put out, hoping to slip through the blockade without incident. But it isn’t to be: a Union ship finds and fires on them, and though they run, they can’t hide. The captain of the boat puts Belle under guard in her room, giving orders to have her stabbed if she tries to come out. He asks if she’s scared. “No, I am not.” She says. “I was never frightened at a Yankee in my life!”

So what does she do? Helps the captain escape, get rid of all her secret documents, and seduces the hell out of a lieutenant, of course. She and Lieutenant Samuel Hardinge, when he takes over the Greyhound, seems to make an instant connection. It doesn’t seem to matter to him that she’s a known Rebel spy – Belle’s just fly like that. They’re still on the ship when he asks her to marry him. I guess the whole prisoner/jailor thing didn't bother him at all.

When they arrived in Boston, the government promptly tells her that they want her out of America. So she goes to London, where she begins to write her memoir and plans her own wedding, probably using the money she was supposed to put toward furthering the Confederate cause. But first, there’s the pesky problem of converting her beau into a Southerner. Turns out he’s down with it. The Boston Post said she, “had made a fool of him.”

After the wedding, when her husband goes back to America, he is arrested for his treason. Belle, still furiously penning her memoir, writes to Abe Lincoln to try and blackmail him into letting Samuel walk free again. “I think it would be well for you and me to come to some definite understanding. My Book was originally not intended to be more than a personal narrative, but since my husband’s unjust arrest I had…introduced many atrocious circumstances respecting your government…which would open the eyes of Europe to many things of which the world on this side of the water little dreams.”

We don’t know if he ever wrote her back, but…Belle’s got some cajones.

Meanwhile, back in Richmond, things were just getting more tense for ELIZABETH VAN LEW. Jefferson Davis says that any black Union soldiers found in the south will be enslaved, and their white commanders executed. Spies can be shot dead for helping runaways. There’d been a bread riot in the street: people are starving. Someone throws a death threat at her house, signed “from the White Caps”. Richmond is becoming more dangerous with every passing day.

Meanwhile, John McCullough, one of the guys she’d helped escape by playing dead, is telling General Benjamin Butler all about her. He’s impressed, so he gets a letter through to her, sending a spy along with it, who shows her how to use a special disappearing ink! Revealing it involves spreading tannic acid across the letter, then holding it by the fire to reveal the message underneath. That’s some 007 shit right there! He also gave her a cypher and an odorless/colorless liquid --‘S.S. Fluid,’ he called it--that would turn black when smeared in milk. Since she’d burned through a lot of her riches already with her spy work, Ben also sends her some $50,000 in Confederate money to help cover her recruitment efforts.

And then one night she goes to the back door to find Mary Bowser there. The pressure, and the scrutiny, had become too much. She’s run away from the Confederate White House. The next day, Lizzie puts her friend into a farm wagon, then gets two servants to cover it up with horse manure, and got her smuggled up North and to safety. I guess that’s one way to keep guards from checking it, but…yikes. That’s Shawshank Redemption level gross.

Mary will come back down South after the war, teaching newly freed children at a new school in Richmond, and elsewhere, and give some speeches in New York about her exploits under false names like “Richmondia Richards.”After 1867, she falls off the map. I wish I could tell you more, but we just don’t know.

Lizzie, increasingly paranoid about being watched and eager for the war to end, starts writing to General Grant, leader of the Union army. She hides all of his letters back in hollow lion figurines flanking her fireplace. “May God bless and bring you soon to deliver us. We are in an awful situation here.” She continues to feed him information, helping him foil raids and get closer to conquering Richmond. Later, Grant will write her a letter, saying: “You have sent me the most valuable information received from Richmond during the war.” On March 14, 1865, she sends him enough intel about troop numbers and supplies in Richmond that he’s able to strike the final blow. Imagine it: Richmond, burning, everything was in chaos. Locals run to her house and beg her to hide their valuables: if she IS a spy, which most people suspect by now, they trust the Union won’t burn her house. Union soldiers break out of the prisons, make it to her house, and collapse there. When desperate Confederates come to her house to burn it, she bravely meets them out in the yard.

“I know you, and you, and you,” she said, pointing that spinster finger, “If this house goes every house in the neighborhood will follow.” As so it is that, just as a woman helped win the first battle of the war, another woman helps end it. She raises the U.S. flag over the house, right then and there.

AFTER THE WAR, Belle and Elizabeth both find themselves with troubles and triumphs.

Belle gives birth to a daughter in 1865, then chases continued fame on the theatrical stage. By the 1860s she’d ditched the philandering Mr. Hardinge and was once again stateside, performing a show based on her wartime adventures. She even rode a horse across the stage from time to time. She married again, and somehow ended up having her second child in an insane asylum: oh my. A few babies and several years later, it seems that Belle is losing her grip a bit. She shoots her 17 yo daughter’s boyfriend for supposedly despoiling her, and divorces her second husband when she finds out he had a second wife. Don’t worry: she gets married again less than six weeks later.

But as the war faded into memory, her fortunes fade with it. As we know already, it’s not an easy thing to make a living as a single lady in this century. Especially one who spied for the losing side in a long-ago war. “Life had been crinoline and the smell of roses,” the Washington Daily News wrote of her. “...now...Belle hardened into a strange and frightening thing.” She dies of a heart attack in 1900, at the age of 56. Before she did, she was able to say she didn’t regret a thing. “I have lied, sworn, killed (I guess) and I have stolen. But I thank God that I can say on my death bed that I am a virtuous woman.”

After the war, General Grant visited the South on a tour, and he had tea with Elizabeth Van Lew. When he becomes president years later, he makes her Postmaster of Richmond as one of his first official acts. This is pretty much the highest office a woman could hold at the time, and a well paid one: which is good, because she spent a whole lot of her money during the war.

And oh my, did her southern neighbors hhhhhhaaaaaate this. The Richmond press wrote that Grant had chosen a “dried up maid” who planned to start a “gossiping, tea-drinking quilting party of her own sex”. She kindly declines to comment, except to ask that the press call her postmaster - not postmistress, thanks.

Post offices were not for women, supposedly: real ladies sent their servants for the mail. But during her time as postmaster, she continues to be a badass, hiring several female postal clerks, and some people of color, too - a controversial, and maybe even dangerous, move in the Reconstruction South. She campaigned to get some government money for her war service, but she only got a third of what she requested.

She refused to write a memoir, as she thought that would be ‘in course taste’, but she did write about the many injustices still occurring in the South.

“I tell you truly and solemnly I have suffered. I have not one cent in the world...I am a woman and what is there open for a woman to do?”

Eventually, when Grant left office, she lost her postmaster job. But still, the Richmond community punished her. She couldn’t sell her house; her brother couldn’t get a job. When her mother died, she couldn’t find enough people willing to carry her basket.

Luckily, the many Union soldiers she’d helped save hadn’t forgotten her. They sent her enough money over the years to help her get by. But it sits hard: the fact that her Richmond neighbors refused to forgive her. She, like Belle, died in 1900, aged 82...and, I’m sad to say, died pretty lonely.

For decades afterwards, the people of Richmond swore they saw the ghost of the woman they called Crazy Bet. She haunted her house and the streets around it, saying things like “We must get these flowers through the lines at once, for General Grant’s breakfast table in the morning.” She’s often portrayed as having been a bit crazy: that acting such was how she spied so well. But she was very smart, and very savvy. She used people’s blind spots, her own wits, and her passion for the cause she believed in to help it triumph in the end.

“She risked everything that is dear to man, friends, fortune, comfort, health, life itself,” her memorial stone reads. “All for the one absorbing desire of her heart: that slavery might be abolished and the union preserved.”

19th-century America holds one truth to be self-evident: women aren’t cunning enough to be spies. But these ingenious women volunteered their lives and their services, spending their money and using every trick up their sleeves. They suffered jail and insult, braved battlefields and nighttime picket lines. They pushed back against the notion that women couldn't be good spies, proving that, as Kate Warne once said, women could accomplish things that a man never could.

Voices

Rose Greenhow = Amanda Iman. Check out her lovely podcast Amanda’s Picture Show A Go Go.

Rae Reynolds = the judgy southern belle. Check out her hilarious podcast The Womansplaining Podcast.

Elizabeth Van Lew = Alison Burns & Mary Chesnut = Lulu Picart. Check out their excellent travel/comedy podcast, 10KDollarDay.

Belle Boyd = Kaitlin Seifert

Andrew Goldman

John Armstrong

Avery Downing

Music

“Floating Through Time” by Jeris

“Spring Mvt. 1, Allegro” by John Harrison with the Wichita State University Chamber Players

“A Ghr”and “Cassiopea” by Damiano Baldoni

“Eine Kleine Nachtmusik allegro” by The Advent Chamber Orchestra

All other music from Audioblocks.com.