We Shall Overcome: Elizabeth Keckley and Harriet Tubman

You’re running through trees.

It’s night time, and you’re running through darkness, with nothing to guide you but the stars overhead. You’ve run away from a place that is both home and a prison, leaving behind all you love and know. You don’t know what lies ahead of you. You only know that you will never go back…unless they catch you.

Dogs howl and bay through the woods – you can almost hear your name in their voices. Howling for your blood. But still you run, harder and harder, because you’re running for your freedom. Your life. Terror, desperation…wild, reckless hope. Can you feel it?

Harriet Tubman and Elizabeth Keckley were both born into bondage, and suffered under the yoke of everything the institution of slavery promised. Like millions of other black women in 19th century America, they were victims of a terrible system – and they were also so much more than that. Survivors, fighters, thinkers, dreamers.

These courageous women eventually found lives of freedom, though to get there they took vastly different paths. One ran away, becoming one of the only black female conductors on the Underground Railroad, daring to go back into the south to liberate those still in chains. The other worked hard to buy her freedom, becoming a successful business owner who dressed some of the era’s most illustrious and powerful women. During the Civil War, one helped execute a daring fly-by-night raid that struck a terrible blow to the Confederacy, while the other became a key behind-the-scenes member of Abe Lincoln’s White House, using her influence to start a relief organization to help others.

These women share certain storylines and they diverge wildly in others. But in weaving their lives together, a picture forms of what life was like for an enslaved woman in America, from their time in bondage to the opportunities and trials that came after it. I’m no expert on slavery and race in America, and I’m sure my coverage of these women’s lives will have flaws. But we can’t ignore or skip over these stories. Because The Exploress is all about time traveling back to walk in many different women’s shoes--to try and understand what it was like to be them in their time and place. I don’t profess to truly know what it was to be an enslaved woman in America. But I want to try.

Harriet and Elizabeth did incredible things, made all the more so because of the mountains they had to climb to get there. In our first two-part episode, let’s sink into their stories.

Grab your sewing kit, some sturdy shoes and a will of iron. Let’s go traveling.

MY SOURCES

BOOKS

Behind the Scenes: 30 Years a Slave & 4 Years in the White House: True Story of a Black Women Who Worked for Mrs. Lincoln and Mrs. Davis. Elizabeth Keckley, 1868. Freely available on Archive.org.

The Moses of Her People. Sarah Hopkins Bradford, J.W. Moses, 1886.

Harriet Tubman: The Road to Freedom. Catherine Clinton, Paw Prints, 2008.

Bound for Canaan: The Epic Story of the Underground Railroad, America’s First Civil Rights Movement. Fergus M. Bordewich, Amistad (HarperCollins), 2016.

The Combahee River Raid: Harriet Tubman & Lowcountry Liberation (Civil War Series), The History Press, October 2014.

“Harriet Tubman.” Stealing Secrets: How a Few Daring Women Deceived Generals, Impacted Battles, and Altered the Course of the Civil War. H. Donald Winkler, Cumberland House, September 2010.

America’s Women: 400 Years of Calls, Drudges, Helpmates, and Heroines. Gail Collins, Harper Perennial, 2003.

Mrs. Lincoln and Mrs. Keckly: The Remarkable Story of the Friendship Between a First Lady and a Former Slave. Jennifer Fleischner, Broadway Books, 2007.

Intimate Matters: A History of Sexuality in America. University of Chicago Press (3rd ed.), December 2012.

PODCASTS (my faves are in bold)

Backstory. “A More Perfect Union? The Reconstruction Era.”

Uncivil. “The Raid,” about Harriet’s role in the Combahee River Raid. Oct. 4, 2017.

Stuff You Missed in History Class. “Harriet Tubman and the Underground Railroad, Part 1.” How Stuff Works, June 13, 2016.

Stuff You Should Know. “The Harriet Tubman Story.” How Stuff Works, Feb. 15, 2018.

The History Chicks. “Episode 72: Elizabeth Keckly.” Jul 16, 2016.

Dressed: A History Podcast. “Elizabeth Keckly: “Thirty Years a Slave” to White House Dressmaker,” Apr. 10, 2018.

DIG History Podcast. “Slave Codes, Black Codes and Jim Crow: Codifying the Color Line” and “Celia, A Slave: The True Crime Case that Rocked the American Slave Power.”

ONLINE

“A History of Slavery in the United States: an interactive timeline.” National Geographic Education.

“Rare Photo of Harriet Tubman Preserved.” Mark Hartsell, Medium.com/Library of Congress.

“The Story of Elizabeth Keckley, Former-Slave-Turned-Mrs. Lincoln’s Dressmaker: A talented seamstress and savvy businesswoman, she catered to Washington’s socialites.” Emily Spivack. Smithsonian.com, Apr. 24, 2013.

“Harriet Tubman Historical Timeline.” Harriet Tubman Historical Society.

Harriet Tubman Underground Railroad Museum. I visited this fad museum, and it’s completely lovely. Bonus: the landscape in this part of the Eastern Shore looks just like I imagine it would have when Harriet lived and liberated there. You’ll feel like you’re walking in her footsteps - quite literally.

Drunk History: 304 (Act 1). Comedy Central. I’ve linked you to the Australian Comedy Central video, but just Google “Harriet Tubman Drunk History.” It’s pretty amazing.

“From Indentured Servitude to Racial Slavery.” Africans in America, Part 1. PBS.

“Elizabeth Key.” History of American Women.

“Eli Whitney's Patent for the Cotton Gin.” By Joan Brodsky Schur, National Archives.

“Interracial Marriage Laws History & Timeline.” Tom Head, Thoughtco, Feb. 23, 2018.

“Susie King Taylor (1848-1912).” New Georgia Encyclopedia.

“Slave Medicine.” Lucy Meriwether Lewis Marks, Monticello Library.

“The Birth of Race-Based Slavery.” Peter H. Wood, excerpted from Strange New Land: Africans in Colonial America. Slate.com, May 19, 2015.

“Stitching the Fashions of the 19th Century.” Pam Inder, History Extra (BBC History).

“Innovations in 19th Century Dressmaking.” Crafting Idaho. May 6, 2012.

“Keeping Mary Good Lincoln on Track.” Sarah Booth Conroy, The Washington Post, March 29, 1999.

this portrait of harriet tubman was only unearthed recently, in a forgotten scrapbook. it’s believed to have been taken between 1867 and 1869, when she lived in Auburn, N.Y., where she took care of fugitive slaves in their old age.

Courtesy of the Library of Congress.

transcript

Please forgive any spacing or spelling mistakes. I’m only human!

Let’s start in 1818, the year Elizabeth is born. Here’s where we’re at with slavery: England’s gearing up to end their system. In Haiti, the enslaved have risen up against their French oppressors and won, becoming the first country founded by the formerly enslaved. In America, the abolition movement is picking up steam and the international slave trade has officially ended. And yet the institution only seems to be growing more deeply entrenched in the southern and western states of America. It’s woven into the fibers of the American way of life.

How did America get here? How did slavery become such a prominent piece of the country’s fabric, and so intensely tied to race?

From the very beginning of colonial America, we were laying the foundations for what 19th-century Americans called the ‘peculiar institution’. The slave trade goes back as far as 1619, but it wasn’t gone one day, there the next. Colonists didn’t all decide together, “hey, you know what would be neat?” Like most of history’s worst horrors, it crept in like the kind of insidious fog that you don’t really notice until it’s blinded you. One colony, one law, and one judge at a time.

The colonies needed people to work the fields to get things going, and that often meant women had to go out and work. This was a problem for 17th century colonials because it violated the social and familial order they subscribed to: it was a man’s job to protect his women, both physically and financially, making it possible for them to stay at home in the domestic sphere. Sound familiar? So before long, women working in the fields were seen as being of poor social standing. But more than that, they were also of poor moral standing – seen as ‘common wenches’ who spent the day outside in the public sphere. So as white colonial women moved into the house and more and more colored women – Native Americans, Africans, and others – moved into the fields, physical work, moral standing and skin color started to become weirdly entangled. Which, as we’ll see soon, did not end well for women in the fields.

To fill the fields with people to till it, Europeans hired indentured servants: people from all over the place, of many skin colors – almost always poor, and sometimes criminals – who agreed to work off a several-year period of servitude in exchange for passage to America, room and usually meager board. Conditions could be quite bad, but this wasn’t slavery: indentured servitude had an end date, with the promise of land and eventual freedom. Many of the first Africans brought over to America were treated like indentured servants: so, not like royalty, but with at least the same meager rights and the chance of freedom at the end. Being black in America didn’t mean being a slave – although that possibility was always looming. African Americans owned land, married who they liked, made fortunes.

But indentures were becoming more expensive. Disasters in Europe like the English Civil War meant that indentures were needed back in the motherland. Plus, indentures were uppity, starting rebellions over better work conditions, and eventually posed as competition for the more established. And there was this other thing: white indentures were having mixed-race children with Africans. And that was really rocking the system, and confusing everybody about who was who.

As more black colonials tried to use the law to gain some power – converting to Christianity because the law said they couldn’t be enslaved then, say – the more stringent and race-based the laws became. In 1656 in Virginia, a woman named Elizabeth Key fought her way up the legal chain and sued for her freedom based on who her father was – a white Englishman – and she won it. For some people, this posed a problem. So in colonies like Virginia, which several of America’s founding fathers called home, black women’s work was taxed, while white women’s wasn’t. Black men weren’t allowed to carry firearms.

Why make it so hard to escape a life of servitude? Because, in short, the colonists were greedy. Slaves were cheaper than indentured servants. Bonus: slaves could never leave you, and they’d just keep making more! Yikes. And as indentured servitude started to fall by the wayside, slavery became a raced-based system. Something that, through most of history, it never was before. First, because Africans were apparently easy to kidnap. And while Native Americans were also enslaved, keeping them that way made for an uneasy relationship with the free tribes around you. Africans had no one to fight for them.

Colonialists used all sorts of arguments for this system, all of them tough for us to swallow: that it was the natural order, that the Bible said so. But it seems to me that race-based slavery took hold over time because it made it very easy to see who was who at a glance – to judge and control them.

And thus, by the mid-1650s, the colonies were starting to embrace it. With the rise of rice in the South, that part of America was the most enthusiastic of all.

When it came time to break from ye old mother England, the founding fathers (and mothers behind the scenes) were in a bit of a pickle. Some of them recognized that slavery was not the world’s greatest system, but the economy ran on it, so.... what to do? The Constitution ended up saying that the federal government couldn’t interfere with slavery at the state level. It also allowed for a three-fifths rule: that is, three-fifths of each state’s enslaved population would be counted toward a state’s representation in Congress. The greater a state’s slaves numbers, the more power they’re going to have in politics. I guess that’s why almost all of America’s first 16 presidents were southern slaveholders. Sweet job, Thomas Jefferson!

At the turn of the 18th century, we see the introduction of a game-changing invention: the cotton gin. When young Yale graduate Eli Whitney went down to Georgia to become a private tutor, his quick mind saw an opportunity. Tobacco was declining as a cash crop, and as a rule, cotton wasn’t yet all that profitable. Long-staple cotton fluff was easy to pull out of its seed pods, but that only grew along the coast; the hardier stuff that grew inland was spiky, sticky, and really hard to process at a quick enough pace to make real money. So the inventive Eli got to work on an idea: a machine that automatically sorted seeds and other bits out from the cotton, meaning that it could be processed WAY faster than before. In 1800, the production of raw cotton doubled in yield – and it did every year after that. That's some serious money.

This had such a profound impact on the American economy that every American kid learns about the cotton gin in school. But did you know that Eli’s main backer was a woman? Catherine Greene, his employer, encouraged Eli and gave him money for his project. Oh, Catherine. I wish you hadn’t.

Because the result for enslaved people was devastating. Though the machine made processing faster, and took out the need for human labor, you still needed people to manually pick the crop – and with those doubling yields, they needed LOTS of people. There were fortunes to be made, and as per usual, economic gain trumped morality. The slave trade boomed, spreading out across the south and west. In 1790 there were six so-called ‘slave states’, or states that allowed slavery; by the Civil War 60 years later, there were 15. Between 1790 and 1808, some 80,000 people were stolen from Africa and sold into slavery. Yikes.

The cotton gin helped create what we picture when we think of the antebellum south: that long-porched plantation, surrounded by live oaks, Spanish moss, and fields full of enslaved women of color.

And on that depressing note, let’s join our leading ladies. There are some dark chapters ahead, my friends, but stick with me. These stories will make us appreciate these women’s triumphs that much more.

Elizabeth Hobbs was born in February 1818 in Dinwiddie County, Virginia. I had a friend in college who grew up there, and so I keep wanting to pronounce it the way he did: ‘Dinwiddieeeee’. But anyway. Lizzie was the daughter of Agie Hobbs and George Pleasant Hobbs. At least, George was her father of record: the man whom she called her father and who raised her lovingly as his own. Her biological father was Armistead Burwell, her white owner – let’s put that term in air quotes for the duration - though Lizzie didn’t know that until she was older. Mother Agie was also the product of such a union with a white man. So already, we’re in some deeply troubling waters.

Let me hit you with some law real quick. Back in the 1600s, there were some huge legal shifts that directly affect both of our heroines in a major way. And they all seem to reflect white people’s deep anxieties about interracial coupling.

First we’ve got America’s first anti-miscegenation laws– who, that’s hard to say! - which made interracial marriage illegal. Virginia and Maryland, where Harriet and Elizabeth were born, were two of the first colonies to put this particular gem into practice. But hey, don’t worry white guys: these laws aren’t really aimed at you, though some of you seem disturbingly keen on treating black women like your personal sexual stress reliever. It’s white women getting involved with black men we’re chiefly concerned about. The reason for this seems to be, as the Virginia law states, “For prevention of that abominable mixture and spurious [children],” and as the Maryland law states, to keep women from making “such shameful matches.” Why are we worried about this? Well, because the18th century saw a big uptick in interracial children, and they seem to threaten white power in a way that makes those in charge very anxious. How to tell who is who, with all this mixing and melding? How to keep such children from rising up and killing us all?

The law stated that if you, a white woman, had children with a black man you’d be forced to pay 15 pounds sterling, or risk you and your child forced into indentured servitude. Dear me. Eventually the laws forbade any white person from marrying any black person, free or not, and these laws didn’t totally go away until the 1960s. Ugh, America.

But there are laws aimed at curbing white men’s appetites. In a society where status always stemmed from the father, these broke the mold, saying instead that a child’s status would always follow the status of their mother: partus sequitur ventrum. This was meant to keep white men from getting involved with black women, as any kids born of that union would automatically be enslaved. But did it stop white men from doing what they wanted to do? Not really. It freed them of any responsibility, or punishment, for having mixed-raced children out of wedlock. While for the enslaved, these laws made slavery a system that ran from cradle to grave.

Let’s put this in perspective concerning Elizabeth Keckley. While Lizzie’s father, and probably her grandfather, were white and free, Lizzie is enslaved, not considered a member of his family. She has no rights to his property. She is a slave, and that is all.

Her mother Agie is the family’s seamstress—and ‘mamie’, or nurse—to children who are, lest we forget, Lizzie’s half siblings. I mean....what?

Her father George dearly loves Lizzie and her mother, but is actually owned by another man, and lived elsewhere. Like all marriages between enslaved people, it isn’t legally binding. The law doesn’t demand the Burwells honor it, which means that married couples have to fight to be together, and the threat of separation is never far from their minds.

Both parents can read and write, and they teach their daughter, though it’s hard to say where they learned it: it is illegal in the South for them to learn, considered a threat to the institution of slavery. And it is a threat: education is power. Depriving people of learning is a means of keeping them in chains.

“I have found that, to make a contented slave, it is necessary to make a thoughtless one,” said Frederick Douglass, who escaped from a plantation not all that far from Harriet Tubman’s. “It is necessary to darken his moral and mental vision, and, as far as possible, to annihilate the power of reason. He must be able to detect no inconsistencies in slavery; he must be made to feel that slavery is right; and he can be brought to that only when he ceased to be a man.”

But many people fight to learn anyway. In Savannah, Georgia, a young woman named Susie King, who we talked about in Episode 2 on Civil War nurses, openly defies these harsh laws by attending secret schools run by black women and seeking out help from two white teens. Just so you know, defying such laws will be punished a la The Handmaid’s Tale. Seriously: think about that next time you pick up a book in your leisure time.

Elizabeth Keckley, looking classy and incredibly stylish in a dress she probably made herself.

Wikicommons

The Burwell family’s fortunes are variable. Armistead Burwell and his five sisters lost money in the financial downturn of 1819, just after Lizzie was born, and he had to sell the estate, some land, and some property. What counted as property? You guessed it. In this way, enslaved families live in constant fear of being sold away.

At the of age four, Lizzie is assigned to rock the cradle of the family’s new baby--her half-sister, though of course no one is about to point that out--who is also named Elizabeth. Uuummm. But as a four year old babysitter is wont to do, she rocks the cradle a little too hard. The baby comes tumbling out, and Lizzie panics. She isn’t sure if she’s allowed to touch the baby or not, so she grabs the fireplace shovel and tries to scoop up her charge. Mistress Burwell walks in on this absurd scene and goes completely bonkers. Lizzie is punished with a whipping. At four. Years. Old. She wrote later:

“The blows were not administered with a light hand, I assure you. And doubtless the severity of the lashing has made me remember the incident so well.”

A few years after Lizzie was born, some 250 miles to the north on the Eastern Shore of Maryland, Araminta Ross is born. Her parents call her Minty. We don’t know exactly what year she was born – Harriet thought it was 1825, but her gravestone says 1820. Bad record keeping is one of the many legacies slavery left on the people who suffered under it. So much of their history isn’t written down, because they aren’t allowed to learn how. We don’t know much about her family’s lineage, except that her maternal grandmother was born in Africa and brought over on a slave ship, probably from around the Ivory Coast. Unlike Lizzie, Harriet never learns to read or write - even as an older, free woman. But she could tell a riveting story with the best of them.

Some more law knowledge for you. In 1820, right around when Harriet is born, America sees the signing of the Missouri Compromise. As the country expanded and new states formed, there’s been growing tension about whether new states would be allowed in as slave or free. Such is the case with Missouri. It wants into the Union as a slave state, but that’s a problem: right then, America is balanced 50/50 in terms of freed vs. enslaved. The government doesn’t want to upset that equilibrium by welcoming in a new slave state.

Because slavery is wrong and they want it to fade away, you ask? Well, some do, but sadly that isn’t the main driver…it’s that such an imbalance might give slave owners the winning hand in Congress. So a compromise is struck: let Missouri in as a slave state while admitting Maine as a free state. But also, let’s just draw a line in the sand and say that from now on slavery can’t expand north of the 36’30” parallel. Red Rover, Red Rover, don’t bring slavery right over! Now everyone is happy, right?

Oh no. A lot of people saw it as a terrible omen. Thomas Jefferson wrote that it, “like a firebell in the night, awakened and filled me with terror. I considered it the death knell of the Union.” Well, Jeff, maybe you should have sorted this out properly when you signed the Constitution, instead of fathering several children with an enslaved woman. Just saying.

This compromise further divided the country into North and South, making slavery a southern thing, and freedom a northern one. For both Harriet and Lizzie, this law further chains them to the institution of slavery. It’s as if the Federal government drew a line in the sand and said “you down there, this is just the way it is. Sorry ‘bout it.” Maryland’s Eastern Shore is very close to the Mason-Dixon line – the dividing line between the north and the south. But to Harriet, it must feel like a faraway world.

Harriet is born on or around the Brodess plantation. Her mother is Harriet Green, called Rit, and her father is one Benjamin Ross. Rit is owned by Joseph and Mary Pattison Brodess, while Ben belongs to their neighbor, Anthony Thompson. Not long after Joseph died in 1803, Mary and Anthony got hitched, merging their lands and properties. That included Rit and Ben – just your average morally corrupt Brady Bunch! But that’s how Rit and Benjamin met and fell in love.

She is born somewhere in the middle of a long line of siblings. Her parents love their children deeply. Minty remembered having a cradle lovingly made for her out of a gum tree, probably by her woodsman father. Her mom is a cook for the Brodess family, and given Harriet’s later skill with herbs and cookery, probably teaches her daughter all she knows. So at least Araminta is surrounded by people who loved her.

But in 1822, Minty suffers a blow: she loses her father. Mary Brodess’ son from her first marriage, Edward, has come of age and gotten married, taking all of his property with him – and what counts as property? You guessed it: Rit and her children. Slave marriages aren’t legally binding, and white owners have no incentive to honor them. So now that these parents officially have different owners, they constantly have to negotiate to try and keep their family together.

In this way, enslaved people live in constant fear of separation. Always, there is the threat of seeing a family member sold away, never to be seen again.

It happens more and more after the international slave trade ends in 1807. American landowners still need workers – and if they can’t get them off a boat, they’ll get them from other American plantations. The domestic slave trade becomes big business, many of them coming from upper southern states like Maryland that don’t rely so much on cotton.

And so, white men have all the incentive in the world to get their enslaved women making babies. Despite very harsh conditions in the south for enslaved people, their population rises from 2 million in 1808 to 3.5 million less than 50 years later. Harriet’s locality is a prime place for so called “Georgia traders” to come looking to buy farmhands, especially young ones. In the first half of the 19th century, 10 percent of teenaged slaves in the upper south are sold; another 10 percent are sold in their 20s. Imagine the terror of seeing a child or a sibling sold away down South.

That’s what happens to two of Harriet’s older sisters. All her life, she remembers watching them be carried away, kicking and screaming, their faces twisted with terror. One of them leaves her two children behind her. This loss haunts Harriet Tubman for the rest of her life.

It almost happens to her brother Henry, too, but when Rit happens to see Joseph Brodess take money from a “Georgia man”, Rit takes action. When Brodess calls Henry to the house, she goes instead. Annoyed, he asks why she’d come when it was Henry he’d called. She accuses him flat out of wanting to sell her son. Though Brodess tries to find him, Rit keeps Henry hidden in the woods with some friends for more than a month. He tries to rope another slave in to setting a trap for the boy, but again Rit blocks him. “The first man that comes into my house,” she said, “I will split his head open.” It’s an incredibly brave thing to do, and it saves Henry. In that moment, Rit shows her daughter the importance of fighting for family and what you know in your heart is right.

Despite everything, some of Harriet’s early memories of this place are happy ones. There’s the one about her beautiful cradle. She also remembers some white girls playing with her, throwing her laughing up into the air. Which makes you wonder: at what age would the reality of slavery have sunk in for Lizzie and Harriet? How early on do you think you’d realize what your life would be?

That life is hard. Viewed as a commodity, the enslaved are often given enough food to eat, but it’s mostly pork and corn—and thus they’re surviving, not thriving. While having children is encouraged, pregnant women are often forced out into the fields shortly after giving birth. Fanny Kemble, a slaveholder’s wife down in Georgia, complained that her husband sent women back out into the fields only three weeks after. Though frankly, that’s probably a longer recovery than many. They often have to take their infants out to work with them, and Fanny reported that one of these infants was bitten by a snake, and died.

In both Maryland and Virginia, the swampy conditions in summer means the spread of many diseases, like malaria and yellow fever, and very little medical assistance. The infant mortality rate for black children is some two times higher than for white ones. So is the risk of miscarriage for mothers – no surprise, when you consider the bad food and shoddy living conditions these women are dealing with. More often than not, the enslaved tend to their own sick and pregnant, using a knowledge of roots and herbs passed down through generations. Some black women midwives deliver white babies, as well. They use what comes to hand: sassafras tea to search the blood for what’s ailing you, chestnut leaf tea for asthma, mint and cow manure tea for consumption. Yummy. The enslaved bring seeds and roots with them across the Atlantic, spreading them and their uses. Say, like okra: southern cuisine owes a lot to African plants and technique. There is power in tending to your own community’s ailments, and a healer on a plantation is an almost holy thing. A deep knowledge of the land, and a spiritual connection to it, is something Harriet feels from an early age.

When Harriet is five, her first job is strikingly similar to Lizzie’s. She is loaned out to a neighbor: this is a common practice where a slave is contracted out to someone else: yes, much like you’d hire out a lawn mower from the hardware store. Classy. This neighbor, Miss Susan, wants someone to look after her baby. You don’t think this person is your equal in any way, but you’re going to let her take care of your baby? At five years old? It almost feels like a setup.

But still, Minty has to take care of that baby AND do a full load of domestic work, all while homesick and missing her family. AT FIVE years old. Do you remember being five?

If the baby cries, she is whipped. One day she’s whipped five times before breakfast - she carries the scars for the rest of her life. She’s resourceful, though: she wears thick clothes and pretends the whippings hurt as they’re administered. She is feisty, too: once, while being punished, she bites a man’s knee. For all the good it probably does her.

When she returns home, she is weak, sick, malnourished. Rit nurses her back to health. But she is loaned out, again and again. She does all sorts of chores, all of them gruelling: breaking flax, for example, and wading into waist-high water to catch muskrats. What do you even do with a muskrat? Eat it? Skin it and make a fancy muff?

At seven, Araminta finds the lure of a nearby sugar bowl too tempting. She swipes some, and the mistress sees her. Knowing she’ll be punished, she runs, hiding in a pigpen for five days, fighting the pigs for the scraps. Imagine having to survive like that—being treated like that.

“I grew up like a neglected weed, ignorant of liberty, having no experience of it. Then I was not happy or contented….Slavery is the next thing to hell.”

Meanwhile, Lizzie’s suffering similar trials. One year, her father’s owner moves away because of his failing fortunes, taking George away. It doesn’t matter that he doesn’t want to go – what he wants doesn’t count. “I can remember the scene as if it were but yesterday,” Lizzie recalled. “How my father cried out about the cruel separation; his last kiss; his wild straining of my mother to his bosom; the solemn prayer to Heaven; the tears and sobs--the fearful anguish of broken hearts.”

Though they write letters back and forth, and George swears he’d find a way to come back to them, Lizzie and Agie never see him again. When Agie weeps openly about it, the lady of the house just says,“For heaven’s sake, Agie. There are plenty of men around here. If you want a husband so badly go and find another.”

Shudder. Mrs. Burwell doesn’t like to see their slaves walking around all mopey – probably because it would force her to, you know, except the reality of her terribleness. That the women who serve her are actually human beings with feelings. So Agie, and Lizzie, and all enslaved women, learn how to hide and shove down their feelings “Alas!” Lizzie wrote later. “The sunny face of the slave is not always an indication of sunshine in the heart.”

Southern plantation owners spend a lot of time being fearful about what thunderstorms might be brewing in the hearts of the people sweeping their hearth and cooking their breakfast. And with good reason: the history of slave rebellions in America goes back to 1676. Southern belle Mary Chesnut writes several times in her diary about such an uprising—she grew up with stories of slaves killing masters, writing, “If they want to kill us, they can do it when they please…we ought to be grateful than anyone of us is alive.” In 1831, one Nat Turner and a group of other enslaved people rise up against their owners in Southhampton, VA. It lasts for days, resulting in the murder of some 51 white people. It’s the only truly successful slave revolt in U.S history, and sends serious shock waves through the South. With each revolt comes more restrictive laws meant to suppress them: prohibiting black people from learning to read, from gathering to worship—or gathering to do anything but work.

As Lizzie grows up, her mother teaches her a valuable skill: sewing. A skill like that means being what is called a ‘house servant’: though Harriet will come to loathe such work, it’s generally less physically gruelling than being out in the fields. It also means that she is less likely to be sold away. And though Lizzie is “repeatedly told, when even fourteen years old, that I would never be worth my salt,” she takes to the work, becoming a very skilled seamstress. And that will change the course of her life.

This quilt is attributed to Elizabeth Keckley, made between 1862 and 1880, after Lizzie bought her freedom. It’s made out of scraps of silk, which she probably pieced together with remnants of her clients’s dress materials. As such, it’s likely that some of these scraps were once Mary Lincoln’s.

Courtesy of Kent State University Library.

Eventually, Lizzie is loaned out to her half-brother Robert—yup, you heard that right. He’s married a girl named Anna and needs help setting up his own house. He’s a pretty useless husband, it seems, leaving Anna in a less-than-prestigious situation. Elizabeth is embarrassed by it, too: this assignment is a step down for her. Anna resents what she sees as Lizzie’s lack of deference. So often, she aims her frustration Lizzie’s way. She is screamed at, hit, you name it. But apparently that isn’t enough. One day, Lizzie is loaned out to a neighbor, Mr. Bingham, who tells her to take down her dress for a whipping. She bravely demands to know why. “I was eighteen years of age,” she said,“was a women fully developed, and yet this man coolly bade me take down my dress. I drew myself up proudly, firmly, and said: “No, Mr. Bingham.” Yasssss, Lizzie!

She won’t submit. She says that he’ll have to be stronger than she is if he wants to beat her. Unfortunately, he is: he beats her terribly. And when she stumbles home and asks why they sent her for a whipping, Robert hits her. The horror just keeps piling on, I know.

The beatings from Bingham go on, with no one to stop them. Because in the eyes of the law, this is discipline – not abuse. But she refused to give up her spark - her sense of worth:

“My spirit rebelled against the unjustness that had been inflicted upon me, and though I tried to smother my anger and to forgive those who had been so cruel to me, it was impossible….I told him I was ready to die, but that he could not conquer me.”

Finally, Mr. Bingham feels guilty enough that he stops, saying it’s a sin. You think, Bingham? Go choke slowly on something! But Robert doesn’t. All she can do was write her mother sorrowful letters, to which Agie can do nothing but send her love.

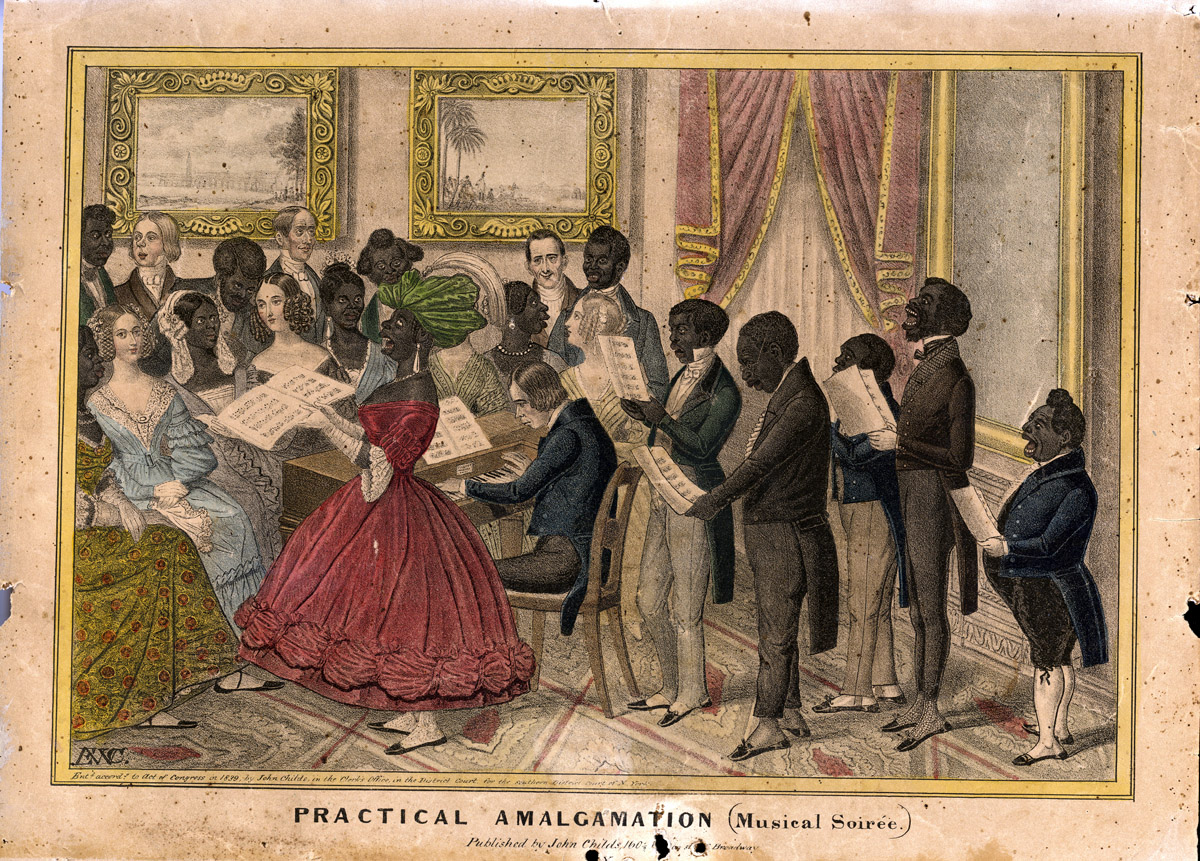

I put this illustration here so that we can all appreciate the image of Lizzie pointing a gun at these people.

Courtesy of the Library of Congress.

This is, needless to say, a bleak time for Lizzie. And I hate to say it, but it’s about to get worse. Around this time, Lizzie is repeatedly raped by a white man named Alexander Kirkland. Angry at his failing fortunes and increasingly to be found wandering around on drunk tirades, this giant of a man keeps finding Lizzie. And though people know about it, they do nothing. For FOUR YEARS. Are you filled with rage yet?

Rape is one of slavery’s best worst-kept secrets. It isn’t something one talks about, but mixed-race children are everywhere you look, laws be damned. And while of course not all southern men participated in it, it was widespread enough that Mary Chesnut wrote: “Like the patriarchs of old, our men live all in one house with their wives & their concubines, & the Mulattoes one sees in every family exactly resemble the white children – & every lady tells you who is the father of all the Mulatto children in every body’s household, but those in her own, she seems to think drop from the clouds, or pretends so to think.”

Here's how former slave Harriet Jacobs put it in her memoir: “Women are considered of no value, unless they continually increase their owner's stock. They are put on a par with animals.”

How do we even explain or begin to fathom this?

Remember that 1662 law that said that said a child’s status follows the status of the mother? What it really means is that it follows the status of the black mother. And remember that all people born into slavery are seen as another commodity to sell and work. And that means that white men have nothing but encouragement, legally, to rape their slaves. They don’t see it as rape at all.

These are extremely murky waters, and difficult ones for the time traveler to swim through. I’m sure there were relationships between white men and black women that involved true romantic feelings. You can still argue that ANY relationship between an enslaved person and a free one is exploitative, the power imbalanced in a major way. And you wouldn’t be wrong.

But here’s what gets me: How can white men watch their child grow up in enslavement? How can their wives watch women being treated like this and not stop it?

We’ll delve into that more in another episode. For now, let’s acknowledge that the blame for such coupling is always blamed on the black woman in question.

Take what happens in 1850, when a man named Robert Newsom buys a teenage girl named Celia. He builds her a private sex cabin and abuses her for years, resulting in children, until a pregnant Celia has finally had enough. A fight ensues, during which she hits him over the head and kills him, then feeds him into her giant fire.

It’s self-defense, but if court is convicted, partially because her lawyer won’t say out loud that she’s been raped. Property can’t be raped, can it? She’s condemned to hang and does, because letting her go would give her humanity and challenge the entire establishment. What I’m saying here is that, if you’re a woman in this situation, you have next to no way to fight this. And that, as former slave Harriet Jacobs writes in her memoir, “There are wrongs which even the grave does not bury.”

Anyway, back to Lizzie. By 24, she has a child by this man, whom she names, quite sweetly, George Pleasant Hobbs. Despite his origin story, she loved her son to pieces. And she will do anything to make him free.

Back in Maryland, age 12, Araminta is officially over the domestic life. While Elizabeth Keckley finds her salvation in sewing, Minty hates being so closely supervised and cooped up for so much of the day. Though she is short – just five feet – she’s strong, and grows stronger as she worked with her brothers in the fields. The labor is by no means easy, but it helps her build her strength and her stamina. She loves nature, and she sees God in it.

As a teen, Amarinta is loaned out to a man named Barrett. When an enslaved man she is working with leaves the property without permission, the overseer goes in hot pursuit. Minty races ahead to warn the man, as he might be punished as a runaway. As Barrett tries to get at the man to whip him, she throws herself between them. You can imagine what happens next.

He picks up a lead weight and hits her with what she recalls as a “...stunning blow.” She said it “broke my skull and cut a piece of that shawl clean off and drove it into my head. They carried me to the house all bleeding and fainting. I had no bed, no place to lie down on at all, and they laid me on the seat of the loom, and I stayed there all that day and the next.”

For weeks Harriet slips between sleeping and waking, falling in and out of a kind of trance. Modern scholars think she must have had narcolepsy or cataplexy, but Minty’s family wouldn’t have known that. For the rest of her life, she’ll have visions and long, trance-like sleeping spells that fall upon her without warning. She has a recurring nightmare about riders coming in and stealing children from their parents. She also has one about being free.

“Flying over fields and towns, and rivers and mountains, looking down upon them like a bird, at last reaching a great fence, or sometimes a river...and just as I was sinkin down, there would be ladies all drest in white over there, and they would put out their arms and pull me ‘cross.”

The upside is that they feel like visions sent to her from God. From now on, she feels firmly that the Lord is there and guiding her.

She is sick in bed for months. When she’s well enough, she goes to work for a man named John Stewart, along with her father and brothers, at his lumber yard. Her father actually earns enough from this work to buy his freedom, but he doesn’t (that comes much later). Why? Because he won’t leave his family. This is yet another way that people of color are kept in bondage. In most states, freed slaves had to carry about freedom papers at all times or risk being put back into slavery. Some states had laws that forced freed people to leave the state within a certain number of months of being free, which often meant leaving their families. Even free, he can’t escape.

Around 1844, Minty ‘marries’ a free black man named John Tubman, though they don’t have any children together. It’s hard to know why, but it’s worth pointing out again that any children of theirs would have been born into slavery. Or maybe it’s that, if she didn’t have children within a few years to provide some extra holdings for her owner’s wealth, he might ‘choose’ a different, more productive husband for her. Yikes.

Meanwhile, she finds some way to see a lawyer about a suspicion: In her former mistress’ will it said, (vaguely), that her mother Rit should have been freed when she turned 45. Since the status of the children follow the mother, any children she had before turning 45 would follow suit. But with the watery wording, the lawyer basically says it isn’t worth trying to fight for. Such a fight against her owners would probably only end in tears. Understandably, this is deeply upsetting to her. Her mother has been living in slavery for an extra decade. It only underlines her resolve to get free.

She blames her owner, Brodess, for keeping her and her family in bondage. First she prays to change his heart, but when she hears rumors that he is going to sell her and perhaps her brothers too, she “...changed my prayer, and I said ‘Lord, if you ain’t never going to change that man’s heart, kill him, Lord, and take him out of the way, so he won’t do no more mischief.” And then he does die, and she feels a bit guilty about that. But I get it, Minty.

With that death comes true upheaval. Will she and her family be sold, separated? Should she risk running away, or stay with them? Should she leave her husband, who doesn’t want to go North? She said: “I had reasoned this out in my mind; there was one of two things I have a right to, liberty or death; if I could not have one, I would have the other. For no man should take me alive; I should fight for my liberty as long as my strength lasted, and when the time came for me to go, the Lord would let them take me.”

And so it is that, in 1849, she runs.

So here we are, running through a midnight wood, with the bloodhounds not too far behind.

When I was young, I always pictured the system that enslaved people traveled to get from South to North – the Underground Railroad – as, you know, a railroad. Everyone shuffled between organized stations, with conductors wearing jaunty hats. But it wasn’t really an official or highly organized network, but a loose and shifting system. “[I guess] I could be called a ‘conductor’ on the underground railway, only we didn’t call it that then,” said Arnold Gragston, who helped ferry his brethren across a river in Kentucky to freedom for four years before he finally did it himself. “I don’t know as we called it anything ⎯ we just knew there was a lot of slaves always a-wantin’ to get free, and I had to help ’em.”

Over time, the Underground Railroad has taken on a misty, romanticized quality, as has Harriet Tubman herself. To understand what Minty is about to go through, we have to wave some of that mist away.

We don’t know when the term Underground Railroad first came into being. It was used as early as the 1830s, when a young enslaved man quoted in a newspaper said he hoped to escape on the railroad that he heard went underground all the way to Boston. Sometimes it was organized: and there were code names for the people and places involved. There were ‘stations’, or houses, that were known to take in runaways, as well as ‘stationmasters’ who ran them and ‘conductors’ who ushered fugitives from place to place.

You’ll often hear that a lot of white people were involved in the Underground Railroad. That’s not untrue: there were plenty of white-run vigilance committees in the North who raised money to help them, and people in the South who helped operate safe houses and transportation, though it was illegal. Amarinta Ross supposedly gave a white woman a quilt in exchange for her help in the beginning of her journey. But in Maryland especially, it was common knowledge that there were pockets of free blacks she could turn to – the fact that there were so many freed people living there made it easier to blend into the crowd as you escaped. The truth is that the vast majority of the people involved in the Underground Railroad, and taking the risks, were black. And really, if you’re Araminta, who are you going to stop and ask for directions? Who are you going to trust your life to: that white guy who might be a Quaker, or someone who looks like you?

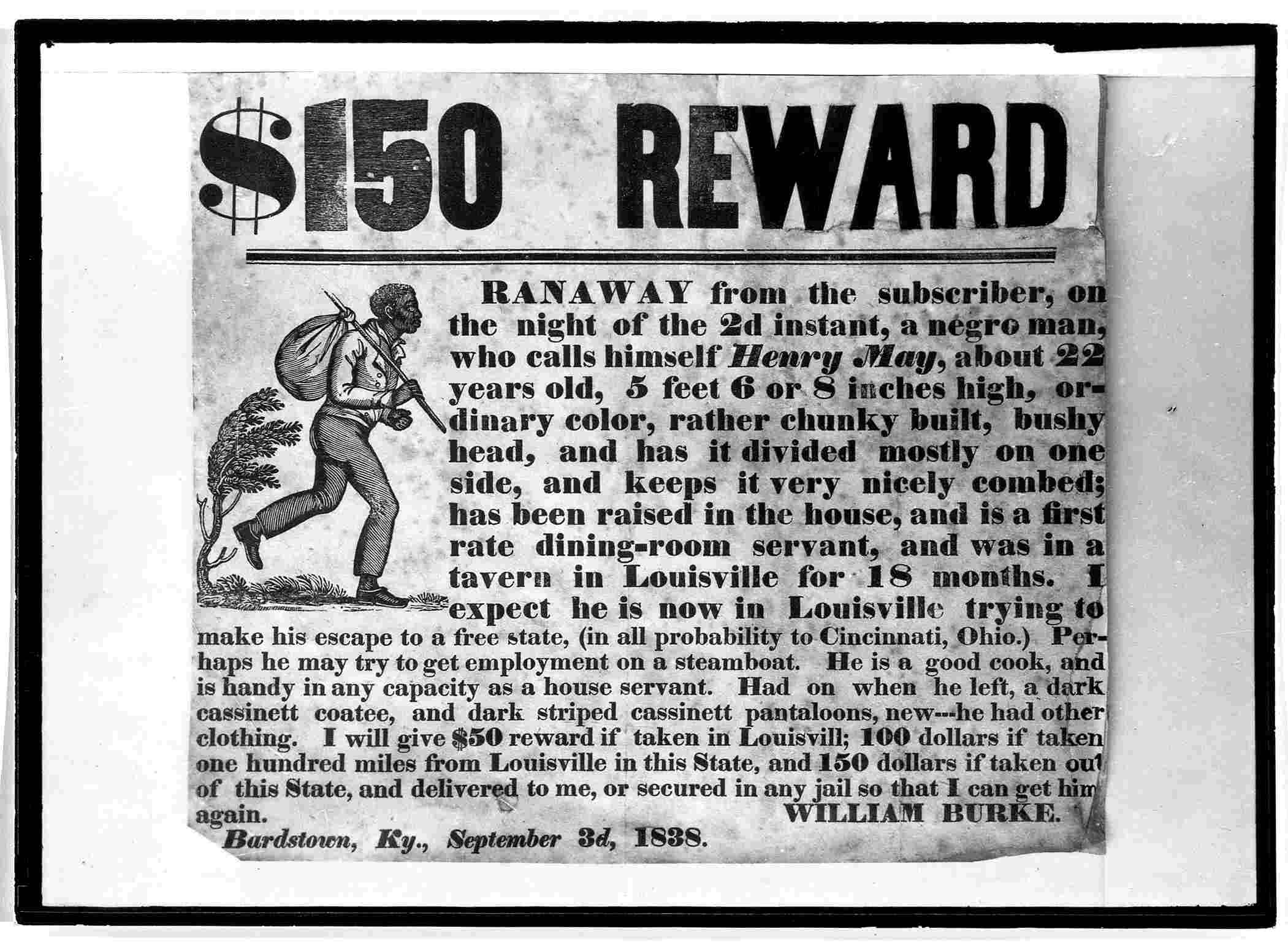

Another thing to consider: Most of the people who escaped from slavery didn’t do so in big groups, or with families. Most of them were young men, and they escaped alone. In a Record of Fugitives compiled in 1855, the vast majority were men around the age of 25. That’s partially because most of these escapes probably weren’t meticulously planned: people saw opportunities arise when they were loaned out, and sometimes had to grab it when they saw it. But it’s also because escaping is really hard. The more people you bring with you, particularly the elderly or children, the less likely you were to make it out without someone finding you. Especially with ‘Slave Wanted’ ads cropping up in local papers, offering rewards for your safe return. Amarinta’s owner puts an ad out for her safe return to the plantation: “MINTY, aged about 27 years, is of a chestnut color, fine looking, and bout 5 feet high.” It offered $50 if she was found in Maryland, and $100 if found outside that state. It was the 19th-century equivalent of the Missing Kid Milk Carton, out there for everyone to see.

Want ads for runaways were common, as were the groups of men who went around looking for runaways to collect on. This notice was put in the paper after Araminta Ross made a run for it.

Courtesy of the Harriet Tubman Byway.

What makes it harder is that most fugitives have no idea exactly where they were going, or how far they’d have to run before they got to safe ground. Every day out on the road made it more likely you’d be caught. It’s telling that most of the people recorded in that Record of Fugitives were originally from Maryland and Virginia, which were closest to the Mason-Dixon line. Very few enslaved people escape from the Deep South. When you are taken away by a Georgia man, it is like a death sentence – you’re unlikely to ever get out of there, and too scared of the consequences to try.

Some people are so afraid of being captured that they found other ways to get themselves up North. After his wife and kids were sold away from him in Richmond, Virginia, a man named Henry “Box” Brown came up with a plan. He paid a white man named Samuel “Red Boot” Smith to pack him up in a crate even smaller than a coffin and ship him up to Philly. Yes: he Fedexed himself to freedom. When he arrived, 250 miles and 24 hours later, the man who opened his box asked, “All right?” And he said, “All right, Sir.” This is insane and amazing, but also sobering. Imagine being so desperate for freedom that you’d pack yourself into a tiny box and trust to providence and the Railroad system. Others followed his example in later years, and some of them died.

This young, twenty-something woman escaped on her own. Two of her brothers started out with her, but decided not to go through with it. So she turned around, took them home, and then struck out by herself. And that is nothing short of extraordinary.

So let’s say we’re running with her. What does that look like? There are tricks for evading slave catchers: only travel by night, and stay off the roads; rub asafetida, an herb that smells a lot like long-unwashed armpit, on your skin to throw off the dogs; follow the North star, also called the Drinking Gourd. Always, she knows there are patrols and local groups on the hunt for escaped slaves. Her knowledge of the land must help her: she knows that the rivers around her home run north to south, so maybe she uses that as a guide. There’s a lot she never said about her escape to freedom. Perhaps because she wanted to protect those who helped her, or just because it was traumatic—an experience she wasn’t keen to revisit. Because imagine how perilous this journey was for her. Imagine how heartbroken she must have been to leave her family behind.

She would have been out in the elements, living rough a lot of the time. As Arnold Gragston recalled of his own experience, “I didn’t know what a bed was from one week to another. I would sleep in a cornfield tonight, up in the branches of a tree tomorrow night, and buried in a haypile the next night.”

Who to trust on her journey? Members of the Underground Railroad developed all sorts of signs to trade by: secret owl calls and catchphrases, and secret knocks on doors. But often, they were loosely knit and informal networks, a la The Handmaid’s Tale, which sometimes would shut down or move if things got too hot. Amarinta would have had no working knowledge of the geography outside of her immediate vicinity, having lived in the same small area all her life. And she wouldn’t have known who was willing to help her and who wasn’t. Sometimes people at safehouses will give escapees scraps of paper with information about the next safe house. They’re meant to verify that the bearer is genuine, not some agent trying to catch those helping fugitive slaves. But since Amarinta is illiterate, she can’t be sure of what it says – all she can hope is that they’ll steer her right.

Escaping slaves got out however they could: by rail or boat, wagon or on foot—but mostly that. Despite a few wagons rides, Amarinta’s journey is mostly on foot, and it’s about 80 miles from her plantation to the Pennsylvania line: it would have taken anywhere from 10 days to three weeks. All of that, knowing that your owner would be looking for you – knowing you would be punished. Who knew what it would be: whipping, branding, perhaps even hobbling. Every minute is an anxious torment. “Though I was not a murderer fleeing from justice, I felt perhaps quite as miserable as such a criminal,” said Frederick Douglass of his escape by train. “The train was moving at a very high rate of speed for that epoch of railroad travel, but to my anxious mind it was moving far too slowly. Minutes were hours, and hours were days during this part of my flight.”

And how does Minty feel, when she finally makes it to Philadelphia? Does she twirl around in the bright lights of freedom? A little bit, sure. But the reality of freedom isn’t the same as the dream. “…there was no one to welcome me to the land of freedom. I was a stranger in a strange land.” She gives herself a new first name to protect her new identity—a symbol of her new life that also honors her family, her past. She takes her mother’s name—Harriet—and keeps her husband’s—Tubman.

But it isn’t easy. She knows no one in Philadelphia. She can’t read; she has no trade to specific skill set to lean on. As resilient as she is, she’s never lived on her own. She finds herself in the same situation as so many who find themselves on the other side of freedom: instead of finding ease and safety, she finds herself on a high wire without any net set underneath. And just because she’s in the north, in Philly, it doesn’t mean that she is safe. There are fugitive slave laws in place that say that escaped slaves must be returned to their owners—or those who help her will be punished by law.

This isn’t new. Fugitive slaves laws were written into the Constitution. With several states in the North already free in the 18th century, the southern founding fathers worries that the enslaved would be able to escape up there and disappear. And that’s true: as more and more people like Harriet get up to cities like Philly, with their growing number of abolitionists, very few people are about to up and tattle. Many resented being told what to do, and just refused to enforce them.

But that doesn’t mean there aren’t bounty hunters up in the North, looking to cash in on runaways. Even more intense: these laws gave some morally black-hearted people incentive to kidnap free black people and sell them off into slavery. Have you seen 12 Years a Slave? You should. It’s a true story. Many African Americans, escaped and legally free alike, were forced down South and into slavery. As Solomon wrote, “...So we passed, handcuffed and in silence, through the streets of Washington, through the Capital of a nation, whose theory of government, we are told, rests on the foundation of man's inalienable right to life, LIBERTY, and the pursuit of happiness! Hail! Columbia, happy land, indeed!”

But the Fugitive Slave law of 1850, around when Harriet escapes, takes it to another level: not only are local northerners compelled to help with the arrest of escaped slaves, but those African Americans are denied any trial, and anyone who interferes will face a $1,000 fine and six months in jail. Such laws are supposed to help avoid war, but all it does is delay it—and deepen the rift between north and south.

A year before Harriet escapes, the country was riveted when some 77 enslaved people stole away through the streets of Washington and hid in the hold of a ship called the Pearl. Those abolitionists sailing it would have to go hundreds of miles to get their charges to freedom. But they were caught in the Chesapeake River, and most of those fugitives were sold down South as a punishment by their owners—and the local abolitionists could do nothing to stop them. Two girls, young Mary and Emily Edmonson, were only saved because a man named Henry Ward Beecher actually raised the money to purchase them from slave traders. The whole thing ignites a fire under the nation, and is part of what inspires Harriet Beecher Stowe to write Uncle Tom’s Cabin.

But for Harriet, this means always looking over her shoulder, living in a climate of fear, suspicion, and doubt. Luckily, she’s an industrious sort. While navigating her new landscape, doing odd jobs to make ends meet, she gets involved with local abolitionists. But still, she is lonely. She misses her family—being free doesn’t mean so much when they’re still in chains.

“My home, after all, was down in Maryland, because my father, my mother, my brothers, and sisters, and friends were there. But I was free, and they should be free.”

She’s set on liberating her loved ones. And in 1850, the same year as that terrible Fugitive Slave Act, she packs her bag and gets ready to do just that.

Meanwhile, down in Virginia, Lizzie is persevering. This tall, confident, resilient woman is only getting better at being a seamstress. She’s sent back to her first home, where her mother is, to Annie Burwell, her daughter Anne, and her husband Hugh Garland. See ya later, terrible Burwell half-sibling!

But the Garland’s fortunes are failing, and so the family moves to Petersburg, then west to St. Louis. They decide to loan Agie out as a seamstress to make some extra money, but Lizzie steps in to take her place. She isn’t about to let her long-suffering mother go out and work for strangers, at her age! Lizzie isn’t willing to put her through that kind of stress.

It isn’t long before she starts attracting the attention of the most fashionable ladies in this monied frontier city. Her clothes are beautiful, her taste exquisite, her designs refined. She’s clearly good at flattering these women, with both her tailoring and her warm manner. And so she makes a lot of money: all of which, of course, goes back to her owner, Hugh Garland. For several years, her salary supports that guy’s entire family. Get off your ass, Garland! Get a job like the rest of us!

At 32, Lizzie is proposed to by a free black man. For a long time she won’t marry him, though, because of what it would mean. Remember that a child’s status always follows that of his mother. And as she said:

“I could not bear the thought of bringing children into slavery—of adding one single recruit to the millions bound to hopeless servitude, fettered and shackled with chains stronger and heavier than manacles of iron.”

This woman is willing to pass on love because she can’t bear to condemn a child to the life she was born into. She knows she has to change her circumstances, but how?

Eventually, she goes to Garland and asked him how much it will cost to buy freedom for her and her son. Garland gives her some cash and basically says: “the state line’s not far away. Illinois’s just there. Go right ahead.” But she doesn’t want to face the same fearful life as Harriet, knowing she might be snatched back into slavery at any time. To her, that isn’t true freedom. They’d never be safe: only hunted. She wants to be legitimately free forevermore.

It’s worth noting that Hugh Garland is the lawyer in the Dred Scott Case in 1857. Dred Scott and his wife had lived for years with their master in a free state, and thus think they should be considered free. So they sue him. Dred Scott loses, because the court declares he isn’t a citizen. Many people call this one of the worst Supreme Court rulings ever of all time. If only Ruth Bader Ginsburg was a time traveler!

This ruling means that no black person, either free OR enslaved, are considered a citizen in the eyes of the law. And Lizzie’s owner helped make that happen.

Eventually, after much pestering, the stab-worthy Garland gives her a number for her freedom: $1200. That’s something like $34,000 today. But how to make it, when she’s giving most of her money over to Garland? He knows she never will.

She decides to go up to New York and pay a visit to a vigilance committee there who help women like her, trying to buy their way out of slavery. But before Anne Garland will let her go, she asks for insurance: in essence, a bunch of white men willing to sign over $1,200 in case she runs away and never looks back. Five of her dressmaking clients’ husbands sign it. But it’s the wives who finally come through in the clutch. The fabulously named Mrs. Le Bourgois comes to Lizzie and says that she doesn’t want her to go up North to find her freedom. “It would be a shame to allow you to go North to beg for what we should give you.”

And so, these ladies pay for her freedom—in 1855, she and her son are officially free. “The earth wore a brighter look,” she wrote,“and the very stars seemed to sing with joy.” And in short order, through her dressmaking, she insists on paying those ladies right back.

Along the road to freedom, she’d married that guy John Keckley, who turned out to be quite a bum. And a liar to boot: he wasn’t actually free, but a fugitive slave, and worse, he drank like a fish. He didn’t make money--he only spent it. So when she gets free, Lizzie isn’t keen to save up the money to help him.“With the simple explanation that I loved with him for eight years, she wrote later, “let charity draw around him the mantle of silence.” So let’s. Boy, bye!

PART 2

We’re back with Part 2 of our exploration of the life and times of Elizabeth Keckley and Harriet Tubman. Last time we heard from our daring heroines, Lizzie had just purchased freedom for herself and her son. But let’s back up a bit and start with the decade leading up to that purchase. While Lizzie’s hustling hard as a dressmaker in St. Louis, Harriet Tubman is back on the East Coast, and she’s also working on securing freedom—but not for her, and not with dollars. No. She promised herself she’d find a way to free her family, and she’s not one to sit around and wait for opportunity. Anyway, she found her own path to freedom--and she’s pretty sure she can do it again.

Between 1850, just a year after escaping slavery herself, and 1861, she returns to the South some dozen times to liberate family members—and some other people, too, while she’s at it. All in all, she rescues around 70 people from bondage—and in all that time, she never gets caught.

Let’s put the outrageous daring of these trips into perspective, shall we? Remember that Fugitive Slave Law from 1850 that said that Northerners can’t shelter runaways – that they even have to help in capturing escaped slaves, if asked? Case in point: in 1849, a bunch of slave hunters raided a popular boarding house in Washington and arrested a waiter in the middle of the dinner service. It must have made quite an impression on Illinois Congressman at the time, Abe Lincoln, who was there to watch helplessly as the man was dragged back into bondage halfway through his evening steak.

This is supposed to be a compromise to appease Southerners—something to stave off talk of civil war. But instead, it’s made many northerners angry. Even people who aren’t abolitionists don’t like it – they don’t think it’s right that the government should force them to aid and abet in the slave trade. As one Columbus newspaper put it, “Now we are all slave catchers.” For those who oppose slavery, it’s a slap in the face of their personal liberty. And one Yankee ship captain barred from docking in Southern ports because of rumors that he’s an abolitionist isn’t afraid to shout out his views on it: “This so-called Fugitive Slave Law…is the most disgraceful, atrocious, unjust, detestable, heathenish, barbarous, diabolical, tyrannical, man-degrading, woman-murdering, demon-pleasing, Heaven-defying act ever perpetrated in any age of the world…”

Being African American anywhere in America got a whole lot more fraught after the Fugitive Slave Law of 1850. Many went up to Canada rather than risk being snatched into slavery.

Wikicommons.

For African Americans, it has immediate and truly dire consequences. Being a black person anywhere in America—free or not—is a dangerous thing. In the first 15 months of the law, some 84 fugitives are shipped back to their masters. “Wo to the poor panting fugitive!” wrote a very frustrated Frederick Douglass. “Wo to all that dare be his friends!” Many are leaving the US altogether, making for Canada, because they no longer feel safe even in the North. People are scared, and rightly so.

But Harriet Tubman isn’t running. Instead, she’s marching in the opposite direction, back into the South—into the flaming arms of danger.

She’s about to become a key conductor on the Underground Railroad: one of the only ones that is formerly enslaved, and one of the only women. This is what she’s famous for—this is what made Harriet into a legend. But her first trip she does her own, without support from anyone. In 1850, she hears that her niece Kessiah Bowley, along with her daughter and young son, are being put up for sale back home in Cambridge. Keep in mind: these sales tend to be a very public spectacle. Most of the town turns up to watch an auction—because sometimes history’s gross like that.

During it, Kessiah’s husband John puts in the highest bid for his wife and children – a princely $500 – and he’s told to stand aside while the auctioneer takes lunch. But when they check into his finances, they find out he’s not good for the money. So they decide to start again: only serious bids this time. But by then, John and his family have already stolen away. They hide in a barn until nightfall, then row through the night up the Choptank River for Baltimore…and for Harriet, who helps hatch the plan for their great escape.

Baltimore’s a good city to start in, as it has a huge free black population that the Bowleys can blend in among. But that doesn’t mean it’s safe—it’s still a southern city. But Harriet guides them through the treacherous streets, somehow, and on to Philadelphia. Again: this is just ONE YEAR after Harriet’s own escape, and southerners are only becoming more vigilant about hunting down runaways. Every step into the south was filled with real and present danger of ending up in bondage yet again.

Now that she’s done it once, she knows she can do it again. By the spring of 1851, she is headed back down South again to rescue her brother James Isaac, and also a few other men who need her help. Later that year, she goes down there AGAIN—this time for her husband, John Tubman. Even though, let’s remember, he is a free man and can come find her anytime he likes. But Harriet’s not about to let that giant red flag stop her: this is their chance to be together, finally, and she’s going to seize it.

As she approaches Cambridge, she sends a message out to John through the grapevine, telling him to come. But he says he won’t, because, wait for it…he’s gotten remarried. Apparently he refuses to even go and tell Harriet to her face. Way to be super stabworthy, John! Loyal-to-the-bone, family-focused Harriet is heartbroken by it. The future she envisioned is gone, now—but then, perhaps this is what God had always intended. She realizes that perhaps these missions is what he’s been calling her to do all along.

“The Lord told me to do this. I said, oh Lord, I can’t – don’t ask me – take somebody else.” But she can’t ignore what he’s asking of her. “I feel that his time is growing near. He gave me my strength, and he set the North Star in the heavens; he meant I should be free.” And he meant for her to free others: she’s sure of it. So she leaves John behind, letting him drop out of her heart. But she isn’t about to let it be a wasted journey. She rounds up 11 people—some family, some strangers—and guides them all the way to Canada. Her career as a UGRR conductor has begun in earnest.

Harriet establishes a pattern: during the summer she saves up money from domestic work in Philadelphia, and accepts financial support from northern friends she’s made in the Underground Railroad network. She waits to make her way south until the weather turns cold – the long nights of winter are best for clandestine travel.

She typically returns to Maryland, where her family is, and where her childhood gave her a good sense for how to navigate the woods and waterways. She usually meets up with fugitives away from their plantations, making it less likely they’ll be recognized as they start to move. Sometimes she makes the meeting place a graveyard, where they will look like a group of mourners rather than a group of people ready to run. She usually sets out for the North on a Saturday, knowing that owners won’t be able to put a notice in the paper until Monday, giving her a little more time. But there are always slave catchers around, and local possies looking to cash in.

She tends to travel by foot, relying on a network of free people of color, friendly Quakers, and UGRR safehouses as she winds her way North. Knowing who to trust is often the difference between life and death, for a conductor, and her instinct never leads her astray. She spends long nights tucked into potato cellars, barns, and hidden rooms, waiting for the right moment. She’s also one of the first conductors to actively use the actual railway—she often takes the train down South instead of walking: it seems crazy, but really, what black woman in her right mind would take a train deep into a slave state? Right? Genius.

She sticks to back roads and little-known byways, hiding if she suspects danger is near. She uses hymns and songs to help guide her fugitives, using them as a kind of code. One for when a group gets separated; another for when there’s a threat lurking nearby.

When she can, she pays for transport, clothing and food for her passengers – when she doesn’t have money to offer, she gives what she has. Once, she pays for food by offering up her underclothes as payment. She spends every cent she ever makes or is given on others. She isn’t afraid of extreme discomfort: going hungry or cold, without sleep or shelter.

She’s an incredibly convincing actress: she can make herself seem young or old, strong or weak, smart or senseless. A friend wrote of her, “she seems to have command over her face and can banish all expression from her features, and look so stupid that nobody would suspect her of knowing enough to be dangerous.” She dresses up in costume, as an old woman or a male farmhand. She carries a book with her, though she isn’t able to read it, to deflect unwanted attention and hide her face from passersby.

And she needs to hide her face, because she isn’t going around to any Southern plantations. She’s going back to her hometown, where people will know her on sight. It must have taken nerves of steel, a will of iron, and a reckless spirit. Once, she even sees her old owner on the street in Cambridge. Good thing Harriet’s cool in a crisis. She tugs on the legs of the chickens she’s carrying, inducing them to run around like crazy so she can put her head down and tend to them. Her old owner passes her by. Whaaaaat?!

The more trips she makes, the more famous she becomes. People know her face. And yet in all these times, and all these trips, Harriet never gets caught – NEVER. “I was the conductor of the Underground Railroad for eight years, and I can say what most conductors can't say — I never ran my train off the track and I never lost a passenger.” She’s right: that’s something most conductors can’t say. Something about how many got caught.

How does she do it? Particularly when, according to both friends and haters, she isn’t nearly as knowledgeable or suave as some of the other conductors? A colleague called her “…unlettered, no reference of geography, asleep half the time.” Jealous much? Abolitionist William Still showed he really knew how to flatter the ladies when he said of her: “…indeed a more ordinary specimen of humanity could hardly be found among the most unfortunate-looking farm hands of the South.” And yet he also said, “…in point of courage, shrewdness and disinterested exertions to rescue her fellow man…she was without her equal.”

One of her secrets to success is her complete faith in a higher power. She feels like he’s speaking directly to her when she falls into her catatonic, trance-like spells while out on missions, going comatose for hours at a time. It probably terrifies the people with her, but not Harriet: in these spells, she feels God is guiding every move she makes. “I never met with any person, or any color, who had more confidence in the voice of God as spoken direct to her soul…” said abolitionist and Harriet fan Thomas Garrett. “And her faith in a Supreme Power truly was great.” Her intuition becomes legendary: she’ll turn left for no reason, only to discover later that she managed to navigate around some slavecatchers. When she gets stuck, she prays, and help always seems to come.

This intuition and faith seem to make her fearless. And in a time when Spiritualism is rampant, this talent strikes awe and respect deep into many hearts. But she can’t always be winging it and trusting in divine inspiration. Harriet is an excellent planner, making contacts where she needs them, but staying flexible in case the situation may change.

And she isn’t afraid to be hard. She insists on drugging babies with paregoric, a tincture of opium, to keep them quiet on the journey. One time, when she’s forced to keep a group in the swamp for a day and night without food to avoid slave catchers, someone gets scared and says they want to turn back. But she can’t risk him going back and giving his old master intel. She calmly pulls out the gun she always carries and tells him, “move or die.” You best believe he moves, and quickly.

And let’s not forget: she’s a woman of color. Southern slave owners are always on the lookout for conductors, but it’s a man they look for; a man strong, hard, and smart enough to pull off such a thing. So, usually a white man. They’re never looking for a five-foot-tall, illiterate black woman with an armful of chickens. But the truth is that women have always been involved with the UGGR: housing, feeding, and nursing runaways. But their inability to take a woman seriously as a conductor becomes one of Harriet’s most valuable tools.

Though Harriet is considered rough of speech and manner, her daring and commitment impress the bright lights of the abolition movement. She even gets a nickname: Moses.

Perhaps her most famous trip takes place on Christmas Eve, 1854, when she makes her way through the rain to her parents’ cabin. That’s where she instructed her brothers - Henry, Ben, and Robert – to meet her. The family is always allowed to meet there at holiday time, making it the perfect time to escape. But Henry is late, because he has a problem: he doesn’t want to leave his pregnant wife. He sits beside her as she goes into labor, trying to decide what to do: stay or go. She begs him to stay; to not forget her and the children. But in the end, he has to go – he’s heard rumors that he is about to be sold away. It’s leave by choice, or by force.

They hide in the corn crib, staring out between the wooden slats and waiting for the rain to stop. Harriet hasn’t seen her mother Rit or father Ben for years, but she’s too afraid to tell them of her presence: if they’re questioned later, she doesn’t want them to have to lie. But her father finds out, so Harriet has someone blindfold him so that he can come and give his children a hug before they go. He walks them part of the way down their path, unable to see them, then listens to them walk away. Eventually, she will go on a trip to free her elderly parents. But imagine the fierce sadness of this night they spent together—imagine the love, and the loss.

She makes her way to her abolitionist friend William Still’s house in Philly. He writes: “Moses arrives with six passengers. Great fears were entertained for her safety, but she seemed wholly devoid of personal fear.” Harriet brings them up to Canada, deemed the only safe place now.

“I wouldn’t trust Uncle Sam with my people no longer, but I brought ‘em clear off to Canada.”

She spends months there with her family, building a community in this new, frigid place, before turning around and repeating the process.

Meanwhile, the public debate about slavery is getting more intense, straying from words and laws to acts of violence. The Civil War may not have started yet, but there’s already a war going on between north and south. Take the Kansas-Nebraska Act of 1854. It lets the people of Kansas and Nebraska decide whether or not to allow slavery within their borders: a state of play called “popular sovereignty”. Though the law is far from popular. It essentially wipes out the long-standing Missouri Compromise that made slavery a southern thing, freedom a northern one, proposing that each state should make up its own mind. Violence erupts, with “free soilers” – people who oppose the spread of slavery – fighting against pro-slavery advocates, in a period of violence that comes to be known as Bleeding Kansas. We’re talking looting, fires, murder. One of the most explosive fighters of them all is an abolitionist named John Brown.

You may have heard of him: he’s the guy responsible for the raid on Harper’s Ferry, Virginia, in 1859—an ill-fated attempt to incite the enslaved in that area to start a riot and take the town back from their masters. A lot of people, including Frederick Douglass, think he’s kinda crazy. But he and Harriet Tubman are friends: he calls her General Tubman. She actually helps raise money and support for his uprising, though luckily she doesn’t go herself. That would have been quite a blow to history.

Like her, he’s deeply religious and uncompromising in the extreme. But he’s also not the best of planners, and his raid ends with his execution. In his last testament, he wrote: “I, John Brown, am now quite certain that the cries of this guilty land will never be purged away, but with blood.”

She’s devasted by his death, which helps fan the flames of the war. “When I think how he gave up his life for our people, and how he never flinched but was so brave to the end; it’s clear to me it wasn’t mortal man; it was God in him.” He also helps to militarize Harriet’s thinking. To see that perhaps this war can’t be won by freeing one soul at a time and taking them to another, freer country. Perhaps it’s time to turn and fight.

And so it is that, in 1860, she makes her first public rescue. A man named Charles Nalle, who escaped from slavery in Virginia, has been living in Troy, New York for years when he is apprehended by a slave catcher. That slave catcher, rather horribly, is his own brother, a free man, who has been paid to do this dirty work. Charles is being held in a courtroom at the Mutual Bank building while his fate is being decided, but everyone knows what that decision will be.

There is a crowd of antislavery supporters outside the courthouse, all shouting, but most observers are barred from entering. But not Harriet. She’s wrapped herself in a shawl, all stooped over, and though she’s only in her 30s, she’s managed to transform herself into an old, harmless scrubwoman.