Augusta: The First Ladies of Imperial Rome, Parts III-VI

It’s 19 CE, and a packed crowd waits under a steely sky at the port town of Brundisium for one of Rome’s favorite imperial daughters to appear on their shore.

Sixty years before, this place saw Mark Antony and Octavian strike up an important Treaty, one sealed by our old friend Octavia. That was a day of feasting and celebration, but this is a day of sadness. They watch as a ship arrives and a woman disembarks. Two of her children stand beside her, eyes cast down in sadness. The woman’s eyes brim with grief for her husband, whose ashes lie in the urn she holds out before her. She doesn’t bother to hide it: she wants everyone to see. And as to the rumors that her husband didn’t just die, but was murdered, she will do nothing to quell the flames of them. In fact, she’s going to fan them. Because she believes that emperor Tiberius is responsible for her husband’s murder. She’s going to make him pay for what he’s done.

Daughter of Rome’s most venerated war hero, favorite granddaughter of its first emperor, wife of one of its most shining imperial stars, Agrippina the Elder was born to be famous. She was born at the Empire’s very beginning, into its ruling dynasty, thrust into the spotlight, whether she wanted to bask in it or not. But she also made her own spotlight, always fighting for what she believes in - and against those who would do her family harm. But in the early days of the Roman Empire, a spotlight can also be a target on your back. Her fame and her name gave her real influence, but often came at a mighty cost...to her, to her husband, AND their children. This is the story of a very public life, full of drama and heartache, restriction and adventure, anxiety and a fury she couldn’t contain. It’s the story of some of Rome’s most formidable women, doing things that women had never done in Rome before.

Lucky for us, we have some familiar time traveling companions.

THE PARTIAL HISTORIANS: I am Dr. G. I am a Roman historian who specializes in the Vestal Virgins. And I am Dr. Rad and I specialize in all things historical filmy…and we're very pleased we are joining The Exploress on this journey through the lives of Roman women.

Grab your purple silk, a shiny sword, and a marble urn. Let’s go traveling.

i will have my vengeance, in this life or the next.

Agrippina Landing at Brundisium with the Ashes of Germanicus, circa 1765, by Gavin Hamilton

my sources

BOOKS

If you’re interested in purchasing either of these you can find them on my Bookshop.org bookshelf!

Agrippina: The Most Extraordinary Women of the Roman Empire by Emma Southon

Caesar’s Wives: Sex, Power, and Politics in the Roman Empire by Annelise Freisenbruch

PODCASTS

The History of Rome by Mike Duncan. I listened to all of his episodes about this period to try and wrap my head around the politics.

Ancient History Fangirl. They have a whole series called “The Ancient-World Stark Family” that covers over all of this juicy drama and I highly recommend it.

Queens Podcast, who has episodes on Aggie the Elder AND Younger. Laugh and learn.

The Partial Historians. Not only did they help me out with this episode, but they have TONS of great content waiting for you to listen to.

Emperors of Rome. I’ve learned a LOT about Ancient Rome from this one, and Dr. Rhiannon is a fount of knowledge.

ONLINE

“Tiberius.” Donald L. Wasson, Ancient.eu.

“How to Poison Like an Ancient Roman.” Nicol Valentin, Medium.com

“Agrippina the Elder: A Woman in a Man's World.” David C. A. Shotte, Historia: Zeitschrift für Alte Geschichte Bd. 49, H. 3 (3rd Qtr., 2000), pp. 341-357.

“Meretrix Augusta: A Literary Examination of Messalina in Tacitus and Juvenal (thesis)” Nicholas Reymond, McMaster University, 2000.

Suetonius, Life of Augustus

Tacitus, The Annals

Juvenal, The Satires

Do i look sad? I am, but i am also out for blood.

Agrippina Landing at Brundisium with the Ashes of Germanicus, Alexander Runciman, 1871. Courtesy of the National Galleries of Scotland, Scottish National Gallery

transcriptS

keep in mind that this was written for audio, so there are bound to be a few typos. It makes me cringe, too. the text in bold is either a quote I made up (so, not historically accurate) or a quote from The Partial Historians, our special guests.

BACK UP: AN AGRIPPINA ORIGIN STORY

To get this story started, we need to back up and rake over some of the coals we burned through in our last couple of episodes. You didn’t think we were done with Livia yet, did you?

So if you haven’t listened to the first two episodes in our Augusta series, then get outta here and do that. This is also the place that I need to remind you that to talk about these women we have to talk a lot about the men around them. The sources on these women are scanty to begin with, and we’re forced to see them through the lenses of writers trying to tell tales about the emperors they’re connected with, using them as a tool for comment on their fitness as leaders. There’s a real lack of sources, but the ones we have are...judgemental. We’ll come back to this as we travel, but it’s important to keep tucked in the back of your mind.

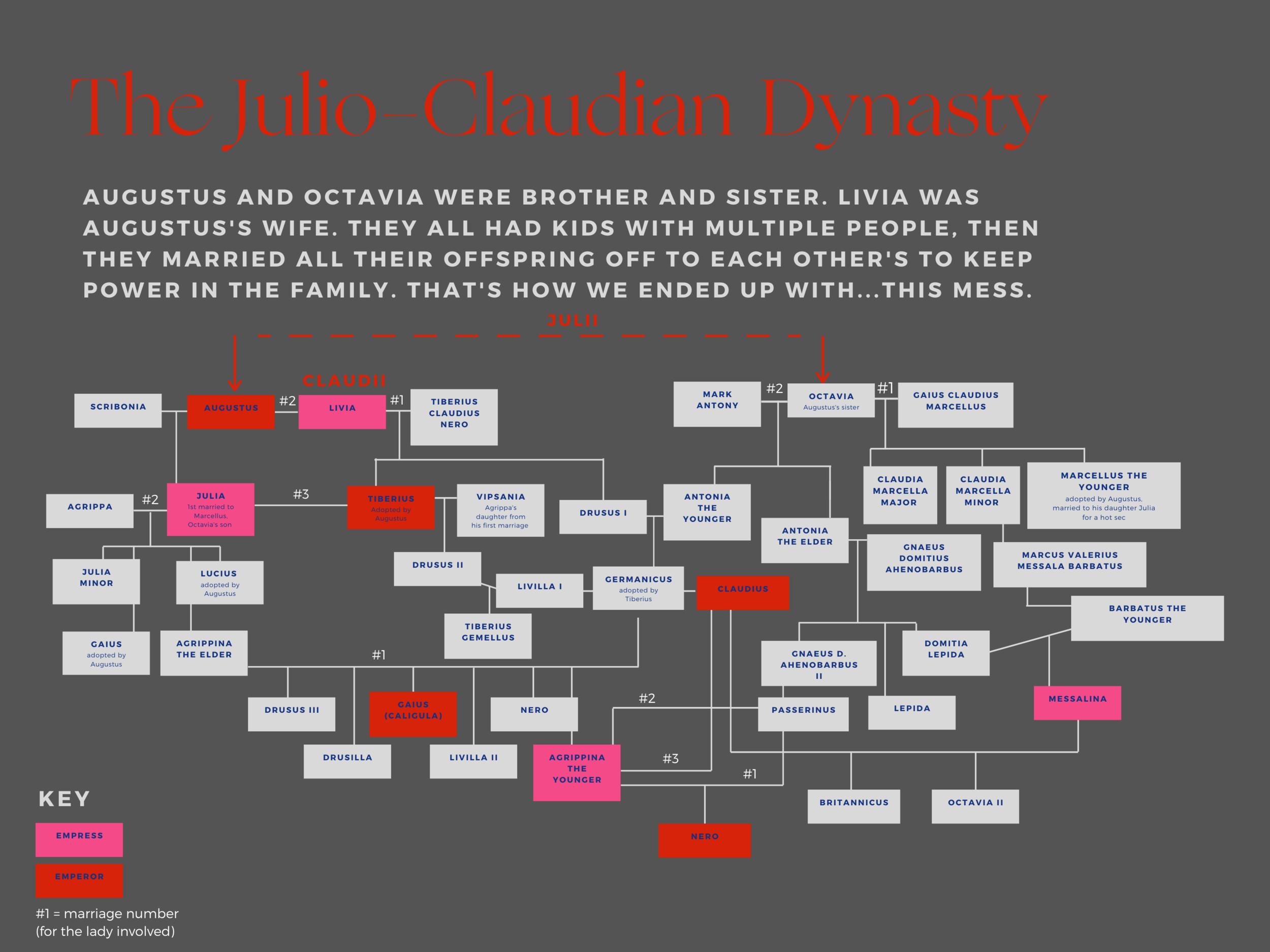

Let’s touch down in 14 BCE. Thirteen years ago, the Senate handed Octavian some extraordinary powers, gifting him the title “Augustus.” He’s been basically running the Roman Empire ever since. In 21 BCE he married his only natural-born child, the wily Julia, to his best friend Marcus Agrippa. Since then, Julia has been dutifully popping out babies, mothering the next generation of the Julio-Claudian clan. Julia sometimes travels with her wayfaring husband, and in October of that year she joins him in Athens. It’s there that she gives birth to a girl named Vipsania Agrippina. Well that’s a mouthful!

Let’s talk about Roman names for a minute. We’ve covered this before, but a little refresher will only help us as we bushwhack our way into the Julio-Claudian tree. Roman men have three to four of them: there’s the nomen, or family name, which tells everyone which gens you’re from. There's the praenomen, which is kind of like a first name: the one only your family will call you. There’s sometimes a cognomen, or nickname, that speaks to a physical characteristic: Maximus, for example, means tall or large. And sometimes there’s a fourth name, the agnomen, an honorific title. Remember Scipio Africanus, Cornelia’s dad? His full name was Publius Cornelius Scipio Africanus: first name, family name, nickname [Scipio means ‘he who bears the staff of authority’, which is impressive sounding], and the honorific, Africanus, given to him because of military successes in Africa.

In ancient Rome, names aren’t just for decoration. They identify where you come from and who you’re connected to, and so they hold a special kind of power. In this patriarchal world, children take on their paterfamilias’ gens name, which is why we have so many same-named children, especially with the ladies. Women tend to get only two names, both related to her father. Agrippa’s full name is Marcus Vipsanius Agrippa, and that’s how she ends up “Vipsania Agrippina.” Lucky her! Since we’re going to spend a lot of time with her daughter soon, who is ALSO named Agrippina, we’re going to call her Agrippina the Elder.

She grows up surrounded by her many siblings: two older brothers, Gaius and Lucius, an elder sister Julia, and an annoying younger brother named Agrippa Postumous.

They are children of the post-Republican era, who have only ever known a Rome in which one man rules, and that man just so happens to be your grandpa AND your paterfamilias. Life as an imperial child has definite benefits and particular perils. Augustus is the richest man in the Empire, and by far the most powerful. And as one of his favorite grandchildren, Agrippina grows up surrounded by attention and interest, basking in the glow of his reflected light. Given all that, you’d think she would have a fairly easy childhood...but it’s full of painful drama from pretty much the very start.

ABOUT TIBERIUS

Augustus thinks a lot about who is going to fill his shoes when he bites it. Sure, Rome isn’t technically a monarchy, but after almost forty years as imperator most Romans can’t remember life being any other way. There’s still a Senate - even if, by this point, it’s more lazy, rich boy’s club than anything like a governing body - but even without it, few people would be likely to complain. After decades of civil war, Rome is peaceful. Under Augustus it’s cleaner, better organized, better fed. But if he doesn’t organize a well-placed and prepped successor, everything he’s built could fall apart when he’s gone. He could die at any time...and if he does, who will carry his mantle? No sons, that’s for sure...he hasn’t managed to have any. So he’s always on the lookout for potential heirs to adopt. Livia is forever campaigning for her son Tiberius, and though Augustus has been his stepdad for pretty much as long as Tiberius can remember, he doesn’t seem to like him much at all.

We met Tiberius in our last episode, but let’s turn the spotlight up on him for a minute, because he’s going to play a major part in Agrippina’s life.

TIBERIUS: I don’t date, so I’m not sure why I’ve been required to write this, but here we are. I’m something of an underdog: the one everyone’s always trying to kick under the table. I don’t know why they’re all so hateful: I’m perfectly charming. I like long, contemplative walks, island vacations, and reading quietly. My perfect Saturday night is me curled up with a book. But instead my world is full of loud, overbearing females. So what if I exile a few of them to islands? So does my stepdad, and everyone loves HIM anyway. It’s so unair, and everything is terrible.

Livia’s son Tiberius (being mopey, as per usual).

From the Romisch-Germanisches Museum, Cologne. Wikicommons.

When Agrippina is born, Tiberius is in his late twenties, in a position of supreme power and privilege. But still, he hasn’t had the easiest time. He lived most of his early life in exile, on the run with his parents. “His childhood and youth were beset with hardships and difficulties,” wrote Seutonius, “because Nero (his father) and Livia took him wherever they went in their flight from Augustus.” Remember that part: his parents were running from AUGUSTUS. The man that, years later, his mom would leave her husband and for. Then at age nine, his dad dies, leaving Augustus as his only father figure. And though his stepdad let Tiberius ride beside him in one of his military triumphs, he never fully takes him under his wing. Instead he favored another boy, Marcellus: he was bright and lively, while by all accounts Tiberius was unhandsome, sour faced, slow of speech, and an all-around Eeyore type. He lives forever in Augustus’ shadow, suffering from his constant disappointment and indifference. At least he has his mom, Livia, though we get the sense that she’s a little bit of a hoverer. More on that later.

It’s not all doom and gloom. Back in 20 BCE, Augustus threw a 22-year-old Tiberius a bone by sending him to Armenia to replace a monarch there. He proved a good commander, but even then Augustus didn’t seem enthused about him. At least he had a lady in his life to soothe his troubles. In 19 BCE, he married Vipsania Agrippina. Wait...our Vipsania Agrippina? Nope: she isn’t born yet. This is one of Agrippa’s daughters from his first marriage. I told you Roman names are confusing! Let’s just call her Vipsania for clarity’s sake. Though probably not of Tiberius’ choosing, it’s a happy marriage: something to distract him when, two years later, Augustus announces he’s adopting some sons, and it isn’t him. It’s young Agrippina’s older brothers, Gaius and Lucius, whom he is grooming as his successors. The emperor pulls his grandsons close, teaching them to read, and swim, and sign documents in the same style as he does. But young Agrippina is much beloved, too. Augustus writes her affectionate letters, praising her intelligence, though he also advises her to cultivate a simpler writing style. Augustus: king of the micromanage.

How does Livia feel about all this? Behind the scenes, she has to be pursing her lips and biting her tongue about her husband’s cold shoulder toward Tiberius. Or maybe she’s just biding her time.

A BRIGHT FUTURE DARKENS

So that’s Tiberius’s situation. All is going pretty well for Agrippina the Elder…until her dad Agrippa dies in 12 BCE. She never has the chance to get to know him. What’s worse, his death means she’ll spend the rest of her childhood in Augustus’ house, under his extremely controlling thumb and exacting standards. He has his granddaughters taught to spin and weave, like proper matrons. He also keeps them quite isolated, separate from most people, but still forbids them from doing anything that can’t be witnessed by a crowd. Someone is always watching, he taught them. Nothing about your life is yours alone.

Augustus is devastated to lose his oldest, most trusted friend. If Augustus died, he was supposed to help Gaius and Lucius out as a sort of regent until they were old enough to take care of things themselves. So now what? He needs another, older heir to groom, just to cover all his bases. Cue Livia sidling up to him for the millionth time to say: have you thought about Tiberius? Augustus is reluctant to entrust his legacy to a boy with, as he put it, such “slow-grinding jaws,” but he’s running out of options, and he trusts Livia. He can’t do much else but agree.

To tie his stepson into the family more tightly, he forces Agrippina’s mom Julia to marry him. Agrippina is only a few years old when her mom is married off, again, to a man not of her choosing. Suetonius tells us that Julia “had a passion for him” even while Agrippa was still living, but truth to tell I think she’s unhappy about this development. By law, she should have been allowed to retire with her trust fund and enjoy life as an independent lady, but her dad Augustus sees her as a tool - one that it’s his right to use. He’s forced to divorce Vipsania, and he is NOT okay with it. It’s said that after, when he sees Vipsania in the street one day, he almost bursts into tears. Oh, Tiberius.

So now Tiberius is technically Agrippina the Elder’s stepdad. How much time does she spend with him? Not much, I’d wager. Between 12 and 6 BCE, he’s sent off to achieve some military greatness in Rome’s provinces, leaving Julia back in Rome to raise the kids alone. He never asked for an adoptive daughter. And why try, when he knows he could never measure up to Agrippa in the eyes of either Julia or Augustus? This guy is already bitter. He’s going to get bitterer still.

As far as we know, Agrippina doesn’t feel any real connection with this man who all but abandons her mother. “I sure don’t. That guy sucks.” But she grows up watching a growing resentment simmering under her mother’s skin, working its way slowly to the surface. She is sick of being caged by her position and her father’s stringent expectations. So she escapes when she can, becoming the star in her own version of Roman Holiday, except featuring a whole lot more nudity. By 7 BCE, she is causing a heaping helping of scandal, indulging in affairs and not bothering to hide them. And then in 6 BCE, Tiberius drops a bomb that blows the family up. “You know what? I don’t even want to be your successor. I’m going to go to Rhodes, kick back with a fat stack of good books, and just chill.” Why the bold move? Perhaps he was sick of being Augustus’s consolation prize successor, but most ancient lay the blame at Julia’s feet. Tiberius really cannot handle her scandal. “I’m a pretty laid back guy,” I imagine him saying, “But I draw the line at my wife having sex with other men in public.”

We can’t know how much Agrippina knew about her mother’s behavior. But she must be shocked when, around the tender age of 12, grandpa Augustus publicly shames Julia, accusing her of adultery and exiling her to a tiny island. She will never see her mom again. Imagine life for Agrippina, living in her grandfather’s house in the wake of her mother’s exile.

As she hovers on that line between childhood and adulthood, she has learned a harsh lesson: blood ties and privilege aren’t enough to protect a woman from the emperor’s judgement.

AGRIPPINA: “I’d really rather not die on an island. Especially if there aren’t any infinity pools or buffets.”

Augustus was controlling of his family before, but now? He’ll do anything to keep them from embarrassing him. Everything Agrippina does is watched and controlled. You have to wonder if she chafes at the confinement, wanting to rage against it. Longing for a way she can be free.

And then in 2 CE, these dark clouds turn into a hale storm. Her brother Lucius dies in a training accident, and two years later brother Gaius follows suit. In her late teens now, Agrippina must be devastated by these losses. But no more so than Augustus - he’s just lost the heirs he poured so much of his time and heart into. He’s going to have to rebuild his succession plans from scratch. Livia may well be sad, too, but there are plenty of rumors that she actually poisoned the boys somehow to make way for her son Tiberius. Augustus has no choice but to call him out of self-imposed exile and line him up to become Rome’s next emperor. And Livia will do whatever she can to help him find his way.

Augustus officially adopts Tiberius at last in 4 CE. But remember, they’re still not blood related, and in Rome that really matters. Augustus himself was adopted, sure, but he was a member of Julius Caesar’s gens to begin with. Tiberius doesn’t have that advantage. So keen for a backup, Augustus also adopts his last living grandson, Agrippa Postumus. And then he looks to his sister’s branch of the family, and his eyes land squarely on a boy named Germanicus.

ENTER ANTONIA AND THE HUNKY GERMANICUS

As we started to discover in our last episode, the Julio-Claudian family tree is a vicious tangle of adoptions and multiple marriages. Add to that the “everyone has the same name” issue and a headache is bound to ensue. I find that visuals help, so I’ve made one of the family tree and posted it in the show notes for you, but let’s skate over it quickly. It’ll help us make sense of what comes next. At the top of the tree are Augustus and his sister Octavia, who form the tree’s two main branches. They’re both Julii. Then there’s Augustus’ wife Livia, who’s a much-revered Claudii. Augustus has one daughter, Julia; Octavia has kids with several husbands; and Livia has Tiberius and Drusus with her first husband, so they’re in the mix as well. It gets confusing when Livia, Octavia and Augustus start marrying their offspring off to each other’s. It’s not just tangled, but also increasingly dangerous for members of the family. The more descendants there are, the more competition there is, and the more factions might form between its members. These alliances and rivalries will shape all of what’s to come.

Germanicus, saying “gather round, ladies, like moths to my flame.”

From the Musée Saint-Raymond (Toulouse). Wikicommons.

So which branch does Germanicus come from? Well, it turns out that Octavia and Livia aren’t the ONLY matriarchs running this show. When Octavia dies, her daughter ANTONIA becomes an important player in the family dynamic. Born in 36 BCE, just before Octavia and Mark Antony broke up, she never got to know her wayward father. This seems to be a recurring theme. She grew up in Augustus’ household with plenty of cousins and siblings: Tiberius, his brother Drusus, wild child Julia, and Antony’s many other kids. Always watched and bound by expectation, she went on to marry Drusus, Livia’s youngest son. And unlike her cousin Julia, Antonia reflects well on her family, dutifully popping out three children without causing any scandals. Then Drusus dies, leaving her a widow at the tender age of 27. She doesn’t remarry, choosing instead to be a univira, or “one-man woman,” just like our old friend Cornelia. She’s borne three children, which means she finds herself in that legal sweet spot those Julian Laws created, allowing her a rare kind of emancipation. The freedom Julia longs for, but never finds. But Antonia doesn’t retire to the country to eat plump figs and read by the pool, though. She stays on the Palatine, acting as Livia’s companion and the family’s other matriarch, though it’s clear she doesn’t quite have Livia’s level of power. They raise the Julio-Claudian brood between them, including her children with Drusus: Claudius, Livilla, and Germanicus. All three will have big parts to play in what comes next.

Claudius is no doubt the little black sheep of the family. Burdened by illness and what scholars now guess was cerebral palsy, Augustus worries a lot about him embarrassing the family. When it comes to any perceived physical frailty, the Romans aren’t kind. As emperor and paterfamilias, Augustus takes the rearing of ALL these kids quite seriously, as we see in this letter he writes to Livia. “As you have suggested, I have now discussed with Tiberius what we should do about your grandson Claudius...the question is whether he has...shall I say?...full command of all his senses...I fear that we shall find ourselves in constant trouble if the question of his fitness to officiate in this or that capacity keeps cropping up…...my dear Livia, I am anxious that a decision should be reached on this matter once and for all….you are at liberty to show part of my letter to our kinswoman Antonia for her perusal.”

This nice thing to note here is that he is making decisions about these kids in close consultation with Livia. The less nice thing is how he treats Claudius like a disease. Livia, too, looks down on him. Antonia, his own mother, is reported to have said that he is “a monster: a Man whom nature had not finished but had merely begun.” Yikes, mom. But remember that in Rome, matriarchs aren’t praised for coddling their children. They’re praised for guiding them toward the areas of study that best suit them and for getting them ready for the adult world that will come. Germanicus, though: he is everybody’s favorite. The name Germanicus is an agnomen, awarded to him because of his deceased dad’s victories in Germania. But given his military future in that region, it’s pretty fitting. Boisterous, strapping: now this is a boy Augustus can get behind.

Hey, watch it there small person clinging to my ankle! You never know when I might exile you to an island. xo Augustus

A statue of Augustus. Wikicommons.

In 4 CE he is 19 years old and full of promise. Tiberius is 44, he’s been pulled back to Rome against his wishes, and yet his stepdad STILL doesn’t trust him to run the Empire without some young upstart attached to the deal. He suffers in silence when Augustus makes him adopt Germanicus despite the fact that his own son, Nero Claudius Drusus, is just a few years younger than the boy is. It’s Augustus’ way or the highway, as usual. You have to wonder if the emperor knows that he’s planting seeds of resentment and tension that will grow into choking vines, poisoning his dynasty from within.

From the start, Tiberius sees Germanicus as a rival - for Augustus’ love, for his own son’s prospects, for the Empire’s appreciation. That sour taste must turn into acid when Augustus makes his next move. He decrees that Germanicus will marry his granddaughter, Agrippina, much-loved daughter of Rome’s favorite general, apple of Augustus’ eye. Germanicus is part of the tree already through Octavia, but marrying him to Aggie the Elder will strengthen his ties to the Julii side of the family. This move is clearly meant to mark him as next in line after Tiberius. Augustus can dust off his hands with his legacy assured. Right? Right?!

Does the now 18-year-old Agrippina WANT to marry Germanicus? As per usual, we don’t know, but she will be pretty familiar with him - they probably played together as children. And he’s her own age, so that’s a massive plus. Add the fact that he’s charming, ambitious, strong, and totally swoonworthy, and it seems her paterfamilias could certainly have chosen worse. Plus, marrying him means getting out from under grandpa’s thumb and going on her own adventures.

EXILE ISLAND

You’d think a big ole wedding would help heal wounds and bury old grudges, but Augustus just can’t stop exiling family members. In 6 CE Agrippina’s remaining brother, Agrippa Posthumus, is exiled for his “low taste and violent tempers.” And then her sister, Julia, is exiled as well. Back in 5 or 6 BCE, Augustus married her off and she dutifully had babies for the dynasty, but apparently she inherited their mother’s wild streak. First she built a big, flashy house in the country, which Augustus disliked so much that he had it torn down. Come on, man! Then she has an affair with a senator named Silanus. True to his conservative stance, Augustus sends her off to a lonely island….where she gives birth to her lover’s child, all alone.

Poor Julia(s).

This image comes from a coin, which represents one of the only images we have of Julia the Elder, Augustus’ daughter.

Seutonius tells us that Augustus ordered the child to be exposed, or left out in the elements. Her lover, meanwhile, goes into self-imposed exile, but he’s allowed to return to Rome years later. Agrippina’s sister, though...she’s left to die in exile, like her mother before her. In case you weren’t counting, here’s a little tally for you: Agrippina’s father is dead; her mother is dead, because exile; her sister is dead, because exile; her brother is exiled. She’s the only member of her family left standing.

His harsh decisions do make waves, though, and they’re ones that can’t be easily smoothed over. There are several petitions to let Julia come home again, all of which Augustus refuses. There are several plots to take Julia and Agrippa Postumous from their islands by force, but they’re all put down. All the while, Augustus loudly curses his female offspring. Every time they’re brought up it’s said he sighs, lamenting: "Would that I never had wedded and would I had died without offspring.” He alternates between calling them either his ‘three boils’ or his “three ulcers.” You know what, Augustus? I’m starting to hope that Livia does poison your figs. Agrippina must hear the message loud and clear.

ROME’S CUTEST COUPLE

Luckily the Roman people are over the moon in LOVE with her and Germanicus. If Rome had a Cutest Couple award, they would most certainly win it. They’re young, they’re beautiful, they’re personable: perfect poster children for the next generation of the Empire, shining enough to wipe away the scandals of the past. The uber-hunky Germanicus is put on the political fast track, becoming quaestor in 7 CE some five years before he’s of legal age to do so. He must be a winning orator, because in that post Augustus lets him read some of his speeches. Then he rises to consul in 12 at the very young age of 26, given command of some eight legions - that’s about a third of the army - stationed in Gaul and Germania. He’s about to earn that nickname. I can just feel Tibeirus burning with indignant, mopey rage.

His successful campaigns over the next few years will make him much loved. The ancient writers blow his greatness up to giant, billboard-sized proportions. Tacitus says that his peers believed he “outdid Alexander the Great in clemency, self-control and every other good quality.” Suetonius gushes about Germanicus: he’s smart, he’s funny, he defeats all his rivals and never brags. And through most of it, Agrippina travels with him, impressing everyone she meets.

It helps that she is incredibly fertile. Agrippina must like some serious tent time with Germanicus, because they will have nine kids in total, six of whom will live into adulthood. This is something I’m not sure we dwell on enough in these histories. She has - count it - nine births, often in military camps, and lives through every one of them. She buries three of these children, mourning their loss, while also having to soldier bravely on. This gal has got a bun in the oven pretty much ALL the time. Three boys come first: Nero (though not the one you’re thinking of), Drusus, and Gaius. At least two are born out on campaign, but it’s Gaius who becomes the troops’ favorite teeny mascot. They dress him up in a pint-sized military uniform and tote him around camp, earning him a cute little nickname: “Little Boot,” though in Latin the name is Caligula. A name, it turns out, the boy will never shake.

This is a huge point of pride for Agrippina AND her grandad. And he isn’t above using his great grandkids to prove his own points. When a bunch of equestrians come before him, complaining about the strictness of his Julian Laws regarding its mandate to get married and have a lot of babies, Suetonius tells us he “sent for the children of Germanicus and exhibited them, some in his own lap and some in their father's, intimating by his gestures and expression that they should not refuse to follow that young man's example.”

But things aren’t all roses back in Rome. In Augustus’ final years, he starts to really clamp down on the kinds of things people can write and say about the emperor and his family. Little black sheep Claudius writes a whole history of the Civil Wars, which promptly gets pumped because it’s seen as too real, and potentially embarrassing. And then Augustus makes a trip out to that island where Agrippa Postumous is being kept. We don’t know why: is he looking to see if his grandson might be fit to get back in the line of succession? To see if he’s a threat? We don’t know whether Livia knows about it. Some sources say that Augustus tries to hide the trip from his wife, but she uncovers it. Perhaps she becomes worried that Augustus is angling to change his mind about Tiberius being his successor and starts to hatch some secret plans of her own...

It’s 14 CE now, the year Augustus leaves this earth forever. And that means that, for Livia and Tiberius, for Agrippina and her family, everything’s about to change.

LIVIA’S SON TAKES THE REINS (SORT OF)

The Germanicus clan are stationed in the Rhine when the news comes: Augustus is dead. There’s a lot of shady rumor surrounding this moment: does Livia poison her husband before he can change his succession plans? Does she poison the figs at his request, because he wants to control when and how he goes out? How much does she stage manage the whole thing? The sources love to paint her as cool and ever calculating, but I just don’t buy her offing Augustus. And it’s fair to say she must feel a lot of sadness in this moment, watching her life partner slip away.

But there’s also this: just a day after Augustus passes, someone goes to Agrippa Postumous’ island and murders him. Does Livia give the order, not wanting her son to have any rivals? Does Tiberius give the order himself? Regardless, someone kills Agrippina’s last remaining brother. She is now the only one of his grandkids left alive, and Germanicus is one step closer to being the emperor. It’s a position that they’ll both have to navigate with care.

As Rome goes into mourning, and Livia with it, there is no uproar about going back to a Republic - no rebellion against the idea of having one man in charge. Augustus made sure that Tiberius and Germanicus were the public face by the time he died, with everything they needed to step into power. But still, this moment puts Rome on a knife’s edge. Can Tiberius step up and fill Augustus’ boots? Can anyone? The Senate votes Tiberius princeps, along the title of "Augustus." And Livia becomes Rome’s first dowager empress, entering a political wilderness not yet explored by any Roman woman. Imagine Tiberius reading Augustus’ will out loud to the Senate, only to stumble on this gem: “since fate has cruelly carried off my sons, Gaius and Lucius, Tiberius must inherit two thirds of my property.” One last kick in the teeth from old stepdad. Augustus’s fortune is ridiculously vast - 150 million sesterces - and a third of that wealth goes to Livia.

This is still a HUGE inheritance for a Roman woman. According to the Lex Voconia, a law that’s been on the books since 169 BCE, a women can’t inherit bequests from people with fortunes of more than 10,000 asses (‘As’ as in A-S, a unit of Roman currency, NOT as in donkeys...too bad.) But since it’s Livia, the Senate gives her a special dispensation, so now she’s one of the wealthiest women in the Roman world. This windfall is on TOP of all the farms, brickworks, copper mines, wine presses and Egyptian olive groves she already owns AND the lands her old friend Salome of Judea bequeathed to her. Livia’s already respected and powerful, but in a client-run culture where everyone’s always looking for a benefactor, this wealth makes her more powerful still. But Augustus’ will also gives her another honor: she’s adopted posthumously into his family clan and given the name Julia Augusta. This makes it clearer than ever that Augustus loved his lady: in some ways, this move elevates her status on par with his own.

The Senate also decides to deify the late emperor, creating a cult of the “Divine Augustus.” I’ll bet Julius Caesar would be pleased as punch. And then the Senate is like, “hey, you know who else we think is great? Livia. Let’s make her the priestess of Augustus’ cult.” As we discussed with the Vestal Virgins, religious roles give women power, prestige, and agency in Rome’s official business. Rarer still is a woman actually placed in CHARGE of such a cult.

mom and son ruling together? tiberius does not approve.

Livia and her son Tiberius, AD 14-19, from Paestum, National Archaeological Museum of Spain. Wikicommons.

But they aren’t done. They also want to grant Livia the title of mater patriae, or “Mother of Our Country,” and change Tiberius’ official title to include “son of Livia.” Say what? And Tiberius is like, “ughhhhh. Ball OFF me, mom!” He uses his imperial veto to smack that one down, saying that “only reasonable honors must be paid to women.” Whatever, Tiberius. Jealous much?

What is the deal between mother and son at this point? Livia is his strongest legitimate link to the emperor’s seat, so he can’t exactly push her to the sidelines. But there’s a fine line between publicly venerating a female family member, thus pumping up your own image, and having that female cast too big a shadow over yours. As Cassius Dio said :

“…in the time of Augustus she possessed the greatest influence, and she always declared that it was she who had made Tiberius emperor; consequently, she was not satisfied to rule in equal terms with him, but wished to take precedence over him.”

True or not, this marks the beginning of some serious tension between Tiberius and his mother. She’s always trying to guide him and the Empire to continued greatness; he’s always trying to confine her role. “I’m a grown-ass man, alright? I’m going to be my OWN emperor.”

Perhaps that’s why he turns more and more to his advisors. One of them is a guy named Sejanus. The year he becomes the new emperor, Tiberius appoints him as praetorian prefect, which is the head of the emperor’s personal guard. This is important to the Agrippinas, so stick with me. The Praetorian Guard is an elite unit of the Imperial Roman army that’ve been around since the Republic, serving as bodyguards for high-ranking officials. During the civil wars, they became important in protecting important guys like Mark Antony. Augustus turned them into his own official security: nine cohorts - each of which usually held about 420 men - tasked with guarding his house and everyone in it. With time, their roles expanded: they stepped in to help with firefighting, did crowd control at gladiatorial games and even sometimes fought within them, and acted as a kind of secret police. Augustus spread them out around the city, never wanting them to seem like an overwhelming presence. But as the years go on, these bodyguards become confidants as well as protectors, wielding increasing power and influence. Eventually they will become powerful enough to murder emperors and replace them without fear of punishment. But right now, guys like Sejanus are just bodyguards. Trusted bodyguards. Bodyguards who happen to offer advice, now and then, to an emperor who has spent his life being dismissed and discarded. Sejanus wants Tiberius to succeed - he wants to help him. Doesn’t he? This is a guy who will feature prominently later, so let’s leave that dangling for now.

TROUBLED WATERS

This transition of power is not all running smoothly. Mad about the conditions they’re forced to live under, and wanting the promises that Augustus made to them honored, some of the legions out in the field start rioting, refusing to be quiet until their demands are heard. These troublemakers know that Tiberius needs their support, and they’re going to twist his arm as far as they’re able. They’re poking the new bear to see if it has claws. When some legions take over their camps, then start looting the countryside, going on a big ole riotous bender, he goes so far as to send his son Drusus out to bargain with them. That works for a little while, but soon there are mutinies happening on Rhine, and that means that the hunky Germanicus is responsible. He goes over to the mutinous camp, where the leaders say something rather treasonous: they’ll take out Tiberius for him and put Germanicus in the top spot if he promises to help them. Germanicus puts that down fast, saying he’d rather kill himself, probably hoping that Tiberius’ spies will report THAT back to him. No coup fomenting here, adopted dad! Then he settles all the troops’ demands...WITHOUT waiting for Tiberius’ permission. Oh damn.

Things get so crazy that a teary Germanicus - it seems he did a lot of crying - begs his pregnant wife to flee for her own safety. She’s insulted by the suggestion, saying something along the lines of:

“I am of the blood of the divine Augustus and will live up to it, no matter the danger.”

Eventually she gives in - or, ever Augustus’ granddaughter, does she decide this is a time for some image making? She makes a show of walking through the sea of soldiers in camp, head held high and baby “Little Boot” Gaius clutched in her arms. Seeing her make her way out of camp shames the rioting soldiers: to think, the granddaughter of Augustus has to leave camp because THEY are making it unsafe for her. For shame, boys! And so she does something neither Tiberius or Germanicus could quite muster: she puts the riots to rest without having to promise one damn thing. “Agrippina’s position in the army already seemed to outshine generals and commanding officers,” Tacitus tells us. “And she, a woman, had suppressed a mutiny which the emperor’s own signature had failed to check.” She steps into a role held by Octavia before her: that of the brave, stalwart peacekeeper. A role tailor made for a woman to play. And though she shares Octavia’s loyalty and steadfastness, Agrippina is much more openly passionate, unafraid to fight for what she believes in. She isn’t going to be sent back to Rome, bound up in propriety and silence. This lioness is going to stay at the front, where she belongs.

The problem, Germanicus decides, is that the troops are bored. They need a task to keep them busy. So he takes them across the Rhine to do some pillaging in Germania.

Specifically, he takes them back to the Teutoburg Forest. In 9 CE, the legions had suffered one of their most humiliating defeats of all time in this forest. It was one of the Empire’s greatest sore spots, and one of Augsutus’ greatest shames. It’s a big part of the reason that before he died, he put a stop to expanding the Empire’s borders any further. But in a brilliant PR move, Germanicus takes them back there, again without Tiberius’ permission, skirmishing with the Germanic chief responsible for that great defeat. It isn’t a resounding success, but he manages to kill a bunch of Germans and recapture some of Rome’s golden standards, which they took into every battle. This made him an absolute legend.

That’s right. Bow down.

Agrippina the Elder with her kids on campaign, Philadelphia Museum of Art.

But it has its touchy moments. Once ,when enemy forces threaten to surround and overwhelm his troops, they hightail it toward the bridge the Romans built across the Rhine. The once-again-pregnant Agrippina has set up a field camp nearby, where she’s been nursing the wounded. When the panicked troops suggest burning down the bridge to keep the enemy from getting across it, she stands up, brushes some of the blood off her stola, and is like “now, boys. Let’s get it together.” They can’t destroy the bridge with her standing on it, which she does, welcoming the returning Roman soldiers as they cross it. Now that’s impressive. As Tacitus tells us:

“In those days this great-hearted woman acted as a commander.”

But not everyone is pleased with a woman in the field, traveling freely and engaging in military action. There are plenty who don’t think Agrippina should be there at all. A few years from now, a man named Severus will argue before the Senate that wives shouldn’t be allowed to follow their husbands to military postings. “A female entourage encourages extravagance in peacetime and timidity in war,” he says. Mk, Severus. The issue isn’t just that they’re frail and easily tired, slowing everyone down. No: it’s something much more sinister. “Relax control, and they become ferocious, ambitious schemers, circulating among the soldiers, ordering company-commanders about.” They haven’t forgotten Fulvia, the women who helped raise and command an army against the beloved Augustus. This behavior isn’t womanly. And what if her move into the military sphere turns into a move into politics? What’s to stop Agrippina from wielding that kind of power? And yet she stays with Germanicus, warrior, wife, and mother. Her naysayers aren’t about to stop her.

PARTIAL HISTORIANS: ...she's also coming behind a bunch of other women that have made similar moves. I definitely think of people like Fulvia when I think of Agrippina, you know, as being similarly challenging what is acceptable behavior and what is okay and also fighting for your family. And there's a lot that you can get away with when you're fighting for your family.

Her children will inherit that fire, determination, and her name. In 15 CE, she is born Agrippina Minor. Or, as we’ll call her, Agrippina the Younger.

LIVIA: HOSTESS, DOWAGER...QUEEN?

Back in Rome, Tiberius is getting more anxious about Germanicus’ power by the day. It seems like Livia isn’t too thrilled with Agrippina’s behavior, either. Some sources say she doesn’t like Agrippina--this young woman brazenly stepping out into the public sphere and shaping it to her liking. She and Tiberius are worried by the kind of sway she seems to have with the troops.

It’s just a year into his emperorship and Tiberius is already unpopular. If ancient Rome had popularity polls, Tiberius’s numbers would be in the toilet for sure. But Livia’s power only seems to grow with her position as imperial gatekeeper and hostess. Much like certain first sisters of American presidents will step in to serve as unofficial first ladies if the president is a bachelor, Tiberius’s continued unwedded bliss means that Livia acts as both empress AND a sort of dowager queen. She conducts her own official correspondence, writing to client kings on official business. Sometimes Tiberius’ letters arrive addressed to both him AND Livia. One time the Spartans write Tiberius to say that they’re starting up a cult of the Divine Augustus - and they also write one to Livia separately. As if to say that, look, Tiberius is the emperor, but we all know who really wears the pants around here.

More than that, Livia has become an important patron to Rome’s most powerful senators. She does her own version of the morning salutatio, when Roman men go over to each other’s houses for meetings, striking deals and asking for favors. Let me stress: This is NOT usually a female-run activity. Livia may not be able to go to the Senate, but that doesn’t mean she isn’t pulling serious strings.

Dr. Rad makes this point about Agrippina the Younger, but it’s worth sharing here as we chat about the gal who comes before her.

PARTIAL HISTORIANS: I think her clients are incredibly important. And it's something that could be very easily overlooked, in a way, because…I don't automatically think of women as having clients, because they are still disadvantaged in this society in terms of the rights that they have. But they do, you know, these important women like Agrippina and other wealthy elite women, they absolutely have their own clients. And that takes on a whole new dimension when you're part of the imperial family.

They come in droves, because there isn’t any better patron to score than rich and influential Livia. She gives them money for their daughters’ dowries and sometimes adopts their sons, lending them her lofty status. Ovid, who Augustus had exiled for writing some satire a little too sassily for his liking, writes home to his wife to go see Livia and beg his case for him. “If she’s busy with something more important,” he says, “put off your attempt and be careful not to spoil my hopes.” But he also adds that Livia is no “wicked Procne or Medea or savage Clytemnestra, or Scylla, or Circe…or Medusa with snakes knotted in her hair!” If you met some of these mythical lady monsters in my bonus episode on Greek mythology, then you’ll know this is a not-that-subtle dig at Livia. Especially, at what is seen as perhaps a monstrous kind of womanly power.

PARTIAL HISTORIANS: I think we need to appreciate that women had managed to accrue a certain level of soft power in the late Republic, particularly, and the early Empire already. You look at your you know your Clodias, your Fulvias, your Livias: people who had managed to accrue some serious soft power. So whilst it's obviously a bit of a tightrope walk in terms of how women manage that position, I think you need to understand that it is possible to have a relative amount of power in a system where you are actively disadvantaged officially.

Tacitus seems to think there’s something monstrous about how she uses that power to help her favorite ladies. When her friend Plautia Urgulania finds herself called to a court she owes money to, she refuses the summons and takes refuge with Livia, creating a scandal that only ends when Livia steps in and pays her debt. Is this a female power move or an abuse of her position? The ancient sources say the latter, but I think it shows that Livia isn’t afraid to use her unique position to help women in a system that doesn’t give them much of a voice to speak with. That said, she doesn’t speak up for them all.

Of course, not everyone loves this turn of events. A woman pulling the strings? No thank you. “She had become puffed up to an enormous extent,” wrote Cassius Dio, “surpassing all women before her...” Cassius isn’t the only one feeling salty. Tiberius, too, is growing weary of his overbearing mom. Tiberius vetoes a push to rename the month of October “Livius” - yas, honey - but he does allow her birthday to be celebrated as an official Roman holiday. He knows how important a role she plays in keeping the myth of Augustus alive, legitimizing Tiberius’ place within it. It’s around this time that statues of her start becoming softer, younger, more goddess-like, and she appears on Roman coins. An emperor has to be careful about having too many statues of himself looking godlike, but the women of the family are a different story. By taking likenesses of the goddesses of fertility, the harvest, and motherhood, and carving them with Livia’s face, she becomes more an idea than a threatening reality. But she also becomes more than just the emperor’s mother. They blow up her image and make it larger than life. Idealized and eternal, she becomes as much a symbol as an actual person. A mother not just to Tiberius, but to us all.

Though troublingly for Livia, Agrippina’s likeness is ALSO finding its way into sculpture. The more children she has, the more prevalent her image becomes, her representations looking less and less like Livia’s. They show a strong, striking woman, with thick waves and curly locks, a symbol of youth - here’s the NEW mother of the Empire. And ancient sources suggest that she doesn’t like it...not one little bit.

TOURING THE EAST IN FUN (UNTIL IT’S NOT)

But also, the ever-more-paranoid Tiberius has had it up to HERE With Germanicus. What are we going to do about his growing fame? Well first, he has to suck up his feelings and celebrate it. So he calls Germanicus back in 17 CE in order to throw him a big old triumph. These military parades-slash-raucous street parties aren’t thrown for just anyone: they’re a big deal, meant as a celebration of one’s military greatness. Another great thing - by custom, the great general’s sons get to ride in his triumphal chariot alongside him. But in a new move that suggests some interesting things about a woman’s place in the Empire, his daughters Aggie the Younger AND Drusilla get to ride with him too.

Then Tiberius slaps Germanicus on the back and says: “Great job, Germ. I think it’s time we gave you a promotion.” He sends him out into the East with a Senate-approved “supreme authority.” This sounds good, but really it’s a kind of demotion. It gets Germanicus out of the field, getting him out of the heart of the action, and into what’s essentially a diplomatic tour, where Germanicus and Agrippina are meant to meet with governors, kiss babies, and generate goodwill. In some ways, you could say that Germanicus just got benched beside the water cooler. BUT then again, remember what happened the LAST time we sent a popular Roman into the East with this kind of authority? Oh, right...Mark Antony and Cleopatra totally blew up everything.

Since he’s being forced away from Rome, Germanicus and Aggie decide, they might as well make it a fun family vacation. They stop in at the site of Actium to pay tribute to Germanicus’ fallen ancestor, Mark Antony. They stop in at Lesbos, Sappho’s old island home, where Agrippina gives birth to ANOTHER daughter, Livilla. You have to wonder if she thinks of her mother Julia...she, too, went with her husband on a tour of the Mediterranean. She, too, gave birth while traveling not so far from here. And now it’s HER name that is being carved into placards praising her childbearing prowess. Oh, the intoxicating freedom and power.

The family heads toward Egypt. They take a cruise down the Nile and a walking tour through Alexandria, inspiring love and statues and all sorts of great PR. And then they get a call from Tiberius.

*ring ring*

TIBERIUS: “I distinctly remember saying that no senator can enter Egypt without my permission.”

GERMANICUS: “Sorry, what? I can’t hear you. The line’s pretty bad.”

Egypt is Rome’s crown jewel, providing much of its grain supply. Since Cleo died, it’s basically belonged to the emperor Augustus. If any one general were to take it, they could take everything. Hence the order that no one can go without the emperor’s permission. There’s nothing to SAY that Germanicus and Agrippina do this to piss Tiberius and Livia off, BUT...they must know it’s going to. But this trip isn’t all lotus flowers and pyramids. Trouble is brewing.

BYE, GERMANICUS

In Syria specifically, which is one of the areas that Germnicus is supposed to be running. The governor there, which Tiberius just so happened to appoint at the beginning of Germanicus' journey, is a guy named Calpurnius Piso. His wife, Munatia Plancina, is a good friend of Livia’s. Coincidence? Many think not. The official line is that the emperor sends them to help Germanicus out and support him in the region, but the whispers say their real task is to watch the pair and cause as much trouble as possible. Tacitus says that Plancina is sent specifically by Livia, “whose feminine jealousy was set on persecuting Agrippina.” Yes, Tacitus: blame it on irrational emotion! If true, I think the ever-calculating Livia makes this move hoping to slow down Germanicus and Agrippina’s rise to power and give her unpopular son some room to move. This whole episode is clouded with rumor and supposition, but one thing is clear: Piso, Germanicus and their wives do NOT get along.

When they get back to Syria after their Egypt trip, Piso refuses to follow any of Germanicus’s instructions. Plancina steps into roles meant to be Agrippina’s, openly berating her in front of the troops. Tensions are high, the atmosphere is sour, tempers are fraying. And then, all of a sudden, Germanicus gets sick--REALLY sick. We have no idea what he really dies of, but Germanicus immediately suspects that Piso’s poisoned him. They even find evidence of black magic in their house where they’re staying: potent evidence. Remember that Romans take their curses quite seriously.

PARTIAL HISTORIANS: And curses also sort of function a bit like gossip…So we know that they're given quite a bit of credence. And we know from the evidence that we found for curses that they can get pretty petty, as well.

We can only imagine Agrippina’s feelings as she clutches his hand, watching her husband and protector waste away, powerless to stop it. We can imagine her rage when he looks at her with fading eyes and says to “forget her pride, submit to cruel fortune, and, back in Rome, to avoid provoking those stronger than herself by competing for their power.” Privately, he begs her to beware of Tiberius and Livia.

“They’re behind this,” he croaks. “If you’re not careful, they will come for you.”

At just 33, Germanicus dies, leaving his wife and six children behind him. As she burns his body, his words must ring in her ears: don’t act up. Keep your head down. Don’t get angry. But Agrippina IS angry. There are two roads before her: one would have her a good and proper Roman matron, like Octavia, quietly submitting to her fate. The other is paved in her own desires, her own ambitions, her own desire to see vengeance done. She knows that Tiberius was behind her husband’s murder, and she wants something done about it. She’s used to being adored, and she’s grown used to being powerful. And quiet submission has never been her style.

miss you, germanicus.

Agrippina the Elder Landing at Brundisium with the Ashes of Germanicus, Benjamin West, Yale University Art Gallery

I WILL HAVE MY VENGEANCE

In 19 CE she packs up her kids and her husband’s ashes, then makes her way back to Rome. The journey takes about three weeks, and during it, the news travels ahead of her: Germanicus is dead. The level of mourning for Rome’s favorite hero is off the charts, and just keeps picking up steam.

He’s been poisoned by Piso and Plancina. Plancina even put on colorful clothes, they say, as if in celebration. But who else would want Germanicus dead? The dowager empress, perhaps? Definitely the emperor. So by the time she steps off that boat in Brundisium, Agrippina is tired, grief-stricken, but also full of an undying fury. It burns in her like the hottest kind of flame. She doesn’t bother hiding it from the crowds she’s picked up along her journey. Agrippina the Elder shares many things with her grandpa, and one of them is a genius for optics. She wants Rome to rally behind her, and so she gives them a vision to rally behind.

It doesn’t help that neither Tiberius or Livia show up at the port to welcome her and offer their condolences. It’s conspicuous. And of course all the people on Team Livia Poisoned Everybody Ever thinks that she had some hand in his death. But no matter. As Tacitus says, Aggie is “impatient of anything that postponed revenge.”

Back in Rome, Agrippina has plenty of friends and she makes NO secret of her suspicions. She had her faction want Piso brought to trial, and the hatred for him is so intense that Tiberius can’t save him. But Plancina...now that’s a different kettle of fish. She’s hated, too, but Livia then starts making calls, pulling strings, taking senators aside for a little private talking to. Again, it seems like Livia might just have more power than her son does, because after two days of questioning, Plancina’s let off. Though she has no official power, her word truly matters. And we don’t know how Aggie and Livia feel about each other really, but Agrippina cannot be happy about it.

There’s evidence that Livia, Antonia, Agrippina the Elder, and Germanicus’ sister Livilla are all given some power over the list of honors to go to Germanicus. Though Tiberius has the final say, they’re actively involved in what is in many ways a senatorial duty. One of these is a triumphal arch to be put up in the city, which will feature not just Germanicus and the men in his family but ALL the women. It’s the first evidence we have of a woman other than Octavia and Livia being immortalized in stone within the boundaries of the city. But this collaborative project does nothing to heal the festering wounds within the family. On the day of the funeral, Tiberius is forced to endure a raucous roar of love and approval not for him, but for Agrippina. We’re not just talking about some really loud clapping. They’re shouting out her name, calling her “the glory of her country, the only true descendant of Augustus.” Oh my. This is NOT keeping her head down, and Agrippina knows it. She isn’t ready to step into obscurity; she is Augustus’ descendant, dammit, and basically a princess. “Nobody puts Agrippina in a corner.”

sejanus starts creepin’

The Julio-Claudians being the Julio-Claudians, they all act like they’re still friends in public. But we all know that’s not how it is behind the scenes. And so we circle back to that Praetorian named Sejanus. Picture Iago from Othello, or Jafar from Aladdin: that’s this guy, forever skulking around in the background, poisonously crafty and ambitious as hell. He wants nothing less than to be emperor himself. Over the years, Tiberius has come to rely on him. He’s made sure of it, worming his way into the lonely emperor’s life, cutting him off from friends and family, trying to alienate him from anyone who might burst his cunning plans. He sets about clearing away any obstacles to his own ambition. That includes Tiberius’ son Drusus AND Agrippina’s entire clan.

It doesn’t help that relations between the now 80-year-old Livia and Tiberius are strained to breaking point. They fight more and more, and Tiberius seems increasingly reticent to give her any influence. When he refuses to put forward her chosen candidate for a judges’ position, she gets out some of Augustus’ old letters, full of mean words about Tiberius. After that, he essentially stops speaking to her, removing her from public affairs and forbidding her to hold a banquet in her husband’s memory. Now that’s just petty.

In 23 CE, Sejanus makes some major moves. First, he starts an affair with Germanicus’ sister Livilla, who is currently married to Drusus, Tiberius’ son. He and Sejanus have long loathed each other. Drusus once punched Sejanus right in the mouth, and you know what? I get it. So one night while they’re lounging in bed feeding each other dormice, Sejanus says: “You know what would be great? If we killed your husband. Then I could be emperor when Tiberius dies and you could be my empress. Good idea?” Or so the ancient rumors go. Not long after that whole punching thing, Drusus dies, and Tiberius is heartbroken. Then Sejanus asks if he can marry Livilla, an honor which he’s denied. No marrying into the imperial family for you, Sir! No problem. Plan B: destroy Agrippina and all of her children. Especially her 16 and 17 year old sons, who it looks like Tiberius might just adopt as his successors. Then there’ll be no one left but him to take the throne.

But Agrippina has plenty of friends. She fights Sejanus at every turn, using male proxies in the Senate to fight against laws that don’t suit her. She has a whole network of people working for her family’s interests and doesn’t give one poisoned fig what Tiberius might think. She also refuses to keep a low profile. On New Year’s Day in 24 CE, there’s this religious event where priests publicly pray for the health and wellbeing of the emperor. Somehow, Agrippina manages to arrange it so that the priests pray not only for Tiberius’ health, but also for her sons Nero and Drusus III, without asking Tiberius first. And he is PISSED.

Sejanus uses the opportunity to remind Tiberius just how uppity and terrible Agrippina the Elder is. He also stirs up a lot of legal trouble, drumming up a bunch of lawsuits against her friends and supporters that cost a lot of money and make them all look pretty bad. Around 26, her cousin Claudia Pulchra is charged with immorality, witchcraft, and conspiring against the emperor. Agrippina sees this as a personal attack and is like “I don’t THINK SO.” She marches over to Tiberius, interrupting him in the middle of a religious sacrifice to Augustus. “The man who offers victims to the deified Augustus ought not to persecute his descendents,” she supposedly said. “It is not in the mute statues that Augustus’ divine spirit is lodged--I, born of his sacred blood, am its incarnation!” Damn, girl! Tiberius, apparently, answers her tirade with a Greek epigram: “it is not an insult that you do not reign.” And make no mistake: she would rein if she could. In fact, I think she believes she deserves it.

Her fiery speech makes no difference: Claudia is condemned. And Agrippina can do nothing. She’s once again under constant surveillance, dogged by the shady Sejanus, with all the public love but so little of its power. She’s around 40 now, and her daughter Agrippina’s around 12. It’s from her memoir that we get the following story. Agrippina the Elder gets ill, and so Tiberius comes to see her. Silent tears stream down her face as she begs him to let her remarry. She is sick of being alone--she wants a fresh start, a new champion for her and her children. Imagine the bitter sting of this proud woman, so sad that she allows herself to beg her enemy for mercy. And Tiberius just sighs, gets up and walks out. He will never let her remarry. She will have to fight all her battles alone. Aggie the Younger will never forget it.

Dr. Rad and Dr. G: Yeah, for sure. And it's also the fact that we know what we think we know. There is this bit in Tacitus where he talks about having read her memoirs. And one of the little snippets he gives us is Agrippina the elder crying because Tiberius won't let her remarry and find a new husband and someone else to obsess about other than Germanicus. And the fact that A chased her this. It just shows that she must have written something down about, you know, this whole I mean, really, it's like a decade of family tension after I mean, over a decade, really, if you go all the way to the point where, you know, all of them are dead, as in her mother and her two older brothers, it's such an insane thing that she basically spent, you know, so much of her life with all of this going on around her. And yet we just have so little from her perspective.

And Livia, it seems, does nothing to stop it. It’s easy to get mad at Livia here. You have power, and you’re supposed to be a champion of women. You’re really going to let your husband’s granddaughter languish, essentially under house arrest? Behind the scenes, we don’t know what relations are like between Livia and Agrippina. But the fact remains that, as long as Livia lives, Agrippina and her children do too.

Aggie becomes increasingly paranoid, with Sejanus always whispering that Tiberius is going to poison her, just like he did with Germanicus. One night Tiberius tests her by throwing her an apple, which she places untouched on the table. She might as well have shouted, “I don’t want your stupid poison apple!” After that, things really start falling apart.

In 28 CE, Tiberius decides he’s totally over Rome, and the Senate, and having everyone hate him. It’s time to remove himself to Capri to do some sunbathing, dammit! So that’s what he does. And who does he leave to basically run things in his absence? Sejanus. The guy that killed his son….though he still doesn’t know that. No one does.

That same year, Tiberius arranges for thirteen-year-old Agrippina the Younger to marry a guy named Gnaeus Domitius Ahenobarbus. He’s 20 years older and most definitely not of her choosing. He’s rich, and definitely prestigious. But it also sounds like he’s a real piece of work. Suetonius calls him “Hateful in every walk of life.” Some choice anecdotes about him are that he killed an ex-slave because he was too sober. He ripped out someone’s eye in the middle of the Forum. And he ran over a child in the street with his chariot, just for funsies. And that’s on top of a whole lot of cheating, lying, and generally being a terrible person. He might not be as bad as Tacitus claims - that guy LOVES recording wild pieces of gossip. We don’t know what Aggie the Younger’s experiencing in the private confines of her first marriage, we can’t imagine it’s all good. We’ll circle back to this later.

A year later, still in Rome, Livia’s well into her eighties: outrageously old by Roman standards. But now she falls ill, and then she dies. As wife of the emperor, and then as his mother, she helped shape the budding Empire for some half a century. Was she a cold and calculating woman? A secret poisoner? A manipulative harpy? A loving wife and clever strategist? Perhaps she was all these things, because women are ALSO complicated figures who make complex choices and contain many multitudes. There’s no doubt that she stayed relevant, powerful, and influential for decades. She helped shape a world where Agrippina and her daughters could become powerful in their own right.

Some historians say that Tiberius is sad about his mother’s passing. Others say he’s like, “ugh, FINALLY. BYE.” “...Tiberius neither paid her any visits during her illness nor did he himself lay out her body,” Cassius Dio tells us. “In fact, he made no arrangements at all in her honour except for the public funeral and images and some other matters of no importance.” Yikes. But the Senate is all about honoring Livia: they want to deify her and make all the women of the Empire enter into a full YEAR of mourning. But Tiberius is having none of it. He doesn’t even come to her funeral. Instead, Gaius is the one who gives her funeral oration: that kid otherwise known as Caligula.

And regardless of whether or not she liked Agrippina, Livia clearly had some influence in keeping her alive. Because the minute she’s gone, Sejanus no longer sees any need to be discreet. He writes to Tiberius accusing Agrippina and one of her sons of “unatural love and depravity” - otherwise known as incest. The people make effigies of Aggie the Elder and Nero, marching them over to the Senate to protest in defence of their beloved family. And so they manage to get away, but only barely. Then comes the missing piece of the Annals - who knows what happens in the two years THEY cover? But when it picks up again, Agrippina the Elder and Nero have both been exiled to islands, and Drusus is in jail on who knows what charges. The younger kids move in with Antonia, who you’ll remember is Germanicus’ mother. She is pissed about this whole mess and writes to Tiberius all about Sejanus’ many schemes to try and undermine him. Finally, in 31 CE, Tiberius finally gets wise to Sejanus’ treachery and he’s executed, along with his entire family. Bye, Sejanus! But it’s too late for Agrippina and her sons.

IMPERIAL DOMINOES FALLING

Drusus is reduced to eating the straw of his mattress stuffing, and eventually starves to death. Nero is given a choice to stab himself with a sword or have someone else do it for him. Agrippina is beaten again and again, once so badly that it’s said she loses an eye. Finally, in painful agony and unwilling to let her humiliation go further, she starves herself to death. This proud, headstrong woman who refused to bow to anyone. It’s easy to admire her, even if we wouldn’t have made the same decisions she did. And her end begs the question: what is going to happen to her one remaining son and three daughters? What must Agrippina the Younger, now 16, be thinking as she sees Tiberius burn her family to the ground? Who will she be without them? How will all this darkness shape the woman she becomes?

Here’s Dr. Rad and Dr. G: ...So Agrippina the Younger is only very young. Very, very young indeed, when her father dies. And then she has to grow up amidst all this tension. But by the time she's getting to be a sort of young teenager – a tween, if you will - things have escalated to such a point that her mother and two older brothers are falling afoul of the Emperor Tiberius. And they're being brought up on all sorts of crazy charges like, you know, homosexuality potentially. Definitely some sort of conspiracy....I mean, that has to be super traumatic for your mother and your two brothers to be sent off into exile. And then to die years later, never coming back...And the drama of all of that happening around her...and yet we have nothing about her reaction to it, but it has to have affected her. And I think we have to assume that seeing these kinds of events play out is both a warning and maybe also a bit of a training in what is possible and what is not possible as a woman in this time period in history.

This canny young woman will learn many lessons from her mother’s mistakes - for one, that confronting men head on isn’t a wise path to power for a woman. And after a lifetime of being told she is the blood of the divine Augustus, she does want power; she feels it’s owed her. Without it, men can hurt you. Even the men in your family - the ones who are supposed to protect you. A woman has to find a way to protect herself. But she wants more than protection; she wants to be the hand that wields authority. To get there, though, she will have to walk along a very thin razor’s edge. She is ready to figure out what she needs to do to stay alive, and take her place in the Empire’s ruling dynasty. Perhaps she looks to Livia’s memory for tips on how to keep it.

In terms of Agrippina’s moves and thoughts during this period, the sources are mostly silent. Of course they are: she’s a matrona, not an emperor or a general. Why would we need to write anything down about her? All we know is that she’s still married to that guy Domitius, and that she’s dealing with two sisters in law that she most certainly doesn’t like. One’s Domitia Lepida, and the other’s usually just called Lepida. By the time Agrippina joins the clan she’s had a daughter by her first husband: a girl called Messalina. Remember her, as we’ll be coming back for her later. We know for sure that Agrippina doesn’t have any children with her husband in these years, which seems strange for a young matrona from a very fertile family. Is it that her husband is the horror that certain sources paint him as? Does she have trouble conceiving? Or is it that, for a woman in her family, having a child is actually a politically dangerous thing? Under Great Uncle Tiberius’ reign, any boy child she has would enter the world with a target on its back. The last thing she wants right now is THAT guy’s attention.

Without much else to say about Aggie’s current existence, we turn back to Tiberius and Aggie’s one remaining brother: Gaius, aka Caligula. Let’s meet this teenager properly, shall we?

GAIUS: Well hey there. I don’t know if you know this, but I’m kind of a big deal. People know me. Some women can’t handle my baggage, and it’s true I have a lot of it. You watch most of your family murdered by your Creepy Uncle and see how well adjusted you are, mk?! But I also have a lot of charm, when I’m not trying to kill anyone, and a lot of power, which I only sometimes use to make other people feel bad. At least I love my sisters, which I think should win me some brownie points. And for real, don’t call me little boot. I’ll probably cut you if you do.

I’m going to keep calling him Gaius, except when he’s being especially terrible, because I wouldn’t want to be known by my childhood nickname for eternity. We already know that Gaius was the youngest boy in the Germanicus clan - a great favorite with his parents and Germanicus’ loyal troops. He’s lived through all the same horrors as his sisters: his father’s suspicious death, his mother’s exile, and then the deaths of his two older brothers, punished for what is likely nothing more than having a too-powerful name. He’s too young to be suspected of anything at the time, so he is spared their fates. He moves with his youngest sisters into grandma Antonia’s house, where he lives in relative isolation, kept forcibly out of public life by the great uncle, whom he feels sure is responsible for the demise of his parents; Tiberius should probably have thought twice before leaving this angry young man alone to stew. The emperor also refuses to grant him his toga virilis, and that’s a big and humiliating deal. Remember that in Rome, your clothes say a lot about you. Roman children wear a bulla, a kind of protective amulet, that shows everyone who looks that they’re still considered kids. But when a boy becomes a man, he’s granted his toga virilis - or the “toga of manhood” - gaining all the rights and privileges that comes from being a Roman citizen (and male). It’s a big deal, usually ushered in with much pomp and ceremony. Augustus got his toga virilis at 15, but Gaius won’t get it for many years after that. He is forced to watch all the other boys become men as Tiberius, nervous about the threat he might pose, keeps him safely tucked into the clothes of childhood. It’s humiliating, and it’s rage inducing, and it’s a good thing to remember as we walk through what comes next.

And then, very suddenly, he’s thrown out of his sheltered life into the manhood no one’s really prepared him for, sent to stay with Tiberius on the island of Capri. There are a lot of wild stories about what goes on at Tiberius’ beautiful cliffside abode, called Villa Jovis. Suetonius gives us lots of lascivious details about what Creepy Great Uncle Tiberius gets up to, and none of them are suited to young and impressionable ears. “On retiring to Capri he devised a pleasance for his secret orgies,” he tells us, “Teams of wantons of both sexes, selected as experts in deviant intercourse, copulated before him in triple unions to excite his flagging passions.”

It gets worse from there, with stories involving children that I’m just not going to detail here. Sometimes, if his victims complain, he has their legs broken. When someone displeased him, he has them flung off a cliff into the sea.

GAIUS: Damn, Uncle T. That’s crazy!

The ruins of Villa Jovis, built by Tiberius on Capri. Who knows what kinds of sexcapades went on up in here…

Wikicommons

Is any of this true? A lot of people dislike Tiberius at this point - he’s basically turned his back on Rome and its people - so there’s every reason to blacken his reputation. And our writer Suetonius is Rome’s biggest gossip, so probably not...at least we hope not. But even without all of the debauchery, we can imagine what these years might be like for young Gaius. He’s been cut off from what remains of his family, forced to smile and nod at the man whom he must hate more than anyone in the world. The man that holds his fate - his very life - in his hands. One wrong move and it might be HIM flying over the clifftop. And then there’s young Tiberius Gemellus, Tiberius’ grandson, who is also on the island. Tiberius is either grooming them both as his potential heirs, or playing them off each other, making them both bow and scrape for his approval. Gaius must know he is on dangerous ground. In the years when his father Germanicus was learning how to lead, how to fight, how to serve in Rome, Gaius is trapped in a situation that is, at best, tense and occasionally very boring, and at worst corrupt and abusive. He’ll spend eight very formative years here, and they likely have a lot to do with the man he becomes later on in our story. But let’s fast forward and get back to Agrippina.

In 37 CE, back in Rome, Agrippina’s husband gets embroiled in a nasty court case. A woman is accused of impiety and adultery, and Domitius is called out as one of her many consorts. The list of people pulled into this very public drama is a who’s who of the Roman aristocracy, and so the new Praetorian Guard steps in personally to interrogate them. This is the position Sejanus once held, remember, so it’s got the potential to be a powerful one. Now it’s held by a guy named Macro.

Before the case can really get going, the 77-year-old Tiberius dies. It isn’t clear how he dies: Gaius will later claim he at least THOUGHT about murdering him. Many people whispered foul play, but really, the guy was 77. It also isn’t clear whom he meant to follow in his footsteps. Though we think he wanted his grandson Gemellus to rule, he wasn’t stupid: he would have known the people wouldn’t accept him unless he was attached to the much-loved son of Germanicus. He must also have died knowing that, back in Rome, people have grown to HATE their emperor. In fact, when he croaks, the people basically throw a party. Instead of mournful processions and prayers, there are cries of “To the Tiber with Tiberius!” suggesting they should throw his body in the river rather than give him a proper funeral. Oh my. This cannot be what Livia was hoping for! But then there is also little black sheep Claudius, Tiberius’ brother, but no one’s feeling enthused about that one. And finally there is Gaius, much beloved son of Germanicus, and descended from the Divine Augustus himself. But then there’s also Agrippina and her husband Domitius, who just so happens to be a grandson of Augustus’ sister Octavia. He’s got about as much claim to the throne at this point as anyone. All of a sudden, the accusations against Agrippina’s husband are escalating quickly. He’s accused of incest with his sister, Domitia Lepida. Suddenly the case seems less about the woman who started it and more about a means of nailing Domitius to the wall. Given that Macro becomes a very chummy, very vocal support for Gaius, we have to wonder if he uses the trial to get Domitius out of the path to succession. Is Agrippina involved in these goings on? We have no idea, because nobody wrote about it that we know of. But given how canny she will show herself later - how ambitious, how resourceful - you have to wonder.

BLINDED BY THE LIGHT