Silent No More: American Womens’ Fight for Their Rights

A woman huddles in the corner of a dank, lightless cell.

Rats scurry across the filthy floor, their nails scraping against it. The whole place stinks of sweat and sick. A bowl of something sits near the door, writhing with worms. She won’t touch it. She wouldn’t even if it were the finest banquet. Her head swims, her thoughts a jumble, tension knotted deep in her gut. But her purpose--that hasn’t faded. It never will. She will not eat, no matter what they do to her. She will never give in.

Chains clank: a door opens. The men have come again. Her throat burns in protest, her heart slamming hard against her ribs. She knows what they will do: strap down her hands, shove a tube up her nose, and pour milk by force into her body. She will bleed, and gag, as they tell her that all the other women are behaving. All the rest have chosen to end their hunger strike. She is alone, and weary to her bones, but she will not let them break her. To win women the vote, she will give everything she has.

This Halloween special has nothing to do with poisoners or murderesses or ghosts of any kind. But it is full of the haunting: women being ignored, and abused, and told to be quiet. Women bonding together and turning on each other, too. And I bring it to you now because America is about to cast its vote for its next president. A vote that, until 100 years ago, most women couldn’t cast at all.

The story of the American suffrage movement is long and complex, filled with noteworthy characters, highlights and shadows, and plenty of paths we could get lost wandering down. I’ve posted a list of books, movies, podcasts, and online resources that will guide you down a few of them. But to tell the story fully would take many hours, and that is not my aim here.

I want to explore some of the more haunting aspects of the fight for suffrage, and the dark consequences that come when you don’t have a public voice.

Grab your best white dress, a yellow badge, and a thick skin. Let’s go traveling.

mr. president, how long must we wait?

Courtesy of the Library of Congress

my sources & further reading

This list is a little different than usual, as some of these are sources I used to write the episode and others are here to give you recommended reading/listening/watching. There is SO much to this subject to learn more about - way more than I could include in this particular episode. Some of these I’ve consumed and loved, while others I haven’t yet gotten to. I hope they provide you with a launch point to jump off from! You’ll find notes from me about some of them in bold.

BOOKS (you’ll find many of these for purchase at my bookshelf on bookshop.org. support my show and an indie bookstore!)

America’s Women: 400 Years of Dolls, Drudges, Helpmates, and Heroines by Gail Collins. HarperCollins, 2003. I am obsessed with this book. If you’re interested in American women’s history, you must read.

Sisters: The Lives of America’s Suffragists by by Jean H. Baker

Ask a Suffragist: Stories and Wisdom from America’s First Feminists by April Young Bennett

Suffrage: Women’s Long Battle for the Vote by Ellen Carol Dubois

Free Thinker: Sex, Suffrage, and the Extraordinary Life of Helen Hamilton Gardener by Kimberly A. Hamlin

Mr. President, How Long Must We Wait?: Alice Paul, Woodrow Wilson, and the Fight for the Right to Vote by Tina Cassidy

Amazons, Abolitionists, and Activists: A Graphic History of Women’s Fight for Their Rights by Mike Kendall and A. D’Amico

Vanguard: How Black Women Broke Barriers, Won the Vote, and Insisted on Equality for All by Martha S. Jones

Women Win the Vote: 19 for the 19th Amendment by Nancy B. Kennedy

The Suffragents: How Women Used Men to Get the Vote by Brooke Kroeger

Picturing Political Power: Images in the Women’s Suffrage Movement by Allison K. Lange

Rise Up Women! The Remarkable Lives of the Suffragettes by Diane Atkinson. This one’s about the women of the British suffrage movement, which helped inspired women like Alice Paul and Lucy Burns.

PODCASTS

About suffrage in general

NPR for Wichita - Hindsight: Looking Back at 100 Years of Women's Suffrage. This is a fantastic dive into the movement, in all its complicated glory. It gives a lot of wonderful context and dives into some of the stories and aspects of the suffrage movement that many neglect. I highly recommend it.

IA (NPR) - Black Women, The Right To Vote And The 19th Amendment

DIG History Podcast - 100 Years of Woman Suffrage . DIG has a bunch of great episodes about women in American history, and specifically in politics, and their show notes are incredibly accessible. They have one about Victoria Woodhull that I very much enjoyed.

about specific women

What’s Her Name - THE MUCKRAKER Ida Tarbell

Dressed: The History of Fashion -

Re-Dressed: Styling the American Suffragist, an interview with Raissa Bretaña

Fashion History Mystery #53: Suffragist Herstory: Miss Mabel Ping-Hua Lee

The History Chicks. They have SO MANY episodes about women I mention briefly, and more I don’t. Go and binge!

Queens Podcast

movies

Not For Ourselves Alone: The Story of Elizabeth Cady Stanton & Susan B. Anthony. Ken Burns, 1999.

Iron-Jawed Angels

Suffragette

Selma

ONLINE

“The Declaration of Sentiments.” National Parks Service.

“Lunacy in the 19th Century: Women’s Admission to Asylums in United States of America.” Katherine Pouba and Ashley Tianen. Oshkosh Scholar, Volume I, April 2006, University of Wisconsin.

“Tactics and Techniques of the National Woman’s Party Suffrage Campaign” and “Women of Protest: Photographs from the Records of the National Woman’s Party.” The Library of Congress/American Memory. The “More to the Movement” exhibit and this Gallery of Suffrage Prisoners. The Library of Congress is CHOCK FULL of amazing resources of suffrage and the movement in America.

“How Victorian Women were Oppressed through the use of Psychiatry.” Jenna Blazevich, The Atlantic.

“Compare the Speeches.” The Sojourner Truth Project.

There is a great collection called the “1917 Suite, Silent Sentinels and the Night of Terror” in Blackbird, a joint venture of the Virginia Commonwealth University Department of English and New Virginia Review, Inc., featuring many first-and accounts and writings from women who were involved.

Women Leading the Way: Suffragists and Suffragettes. 100: A Centennial of Woman’s Suffrage.

You’ll find all sorts of good things at the National Women’s History Museum on women’s suffrage. I often referenced this timeline as I wrote my episode, but it’s a treasure trove of suffrage information.

Some articles on the puzzling phenomenon of the anti-suffrage movement.

A Timeline of Women's Legal History in the United States by Professor Cunnea, Stanford Law. This provides a great timeline regarding the legal aspects of women’s rights.

“In 1920, Native Women Sought the Vote. Here’s What’s Next.” By Cathleen D. Cahill and Sarah Deer, New York Times, July-Aug. 2020.

A Century after Women’s Suffrage the fight for Equality isn’t over,” Rachel Hartigan, National Geographic Magazine.

“Arrested and Tortured, the Silent Sentinels suffered for Suffrage,” Tina Cassidy, National Geographic History Magazine. This is the article that got me thinking about producing this episode of the show. It’s evocative, with lots of great pictures.

looking for a tour to explore the history of suffrage? there’s a wonderful company called a tour of her own in washington, d.c. that offers many.

onward.

The cover of the program for the woman suffrage procession of 1913, Library of Congress.

transcript

Please keep in mind that I chop and change a bit as I record, sometimes adding or deleting bits during the production process, so this won’t match the audio exactly.

THE FIRST (OFFICIAL) WAVE

The longing for more rights for women goes back to its colonial foundations. Many of the earliest colonists shipped from countries like England and France were women who didn’t have a lot of them. Some were convicts; others were kidnapped, taken off the streets to feed a dire shortage of colonial wives and laborers; others went voluntarily, seeking escape or a fresh start only to wind up as indentured servants, some living under conditions similar to the enslaved. Women with money and social status did better, but even so, when she married, her rights and property all went to her husband - her keeper, legally speaking. I mean, why should she need it? As Sir William Blackstone, an English jurist, put it, “The husband and wife are one, and the husband in that one.” That only works when “that one” respects his wife and sees her as his equal. And even then, it’s full of holes.

So much needed doing in the burgeoning colonies that, for a time, women did much of the same work that men did, but their wages were consistently lower than men’s. But then again, husbands and fathers often died while women were still young, leaving them land holdings and printing presses, taverns and stores, some of whom made good coin. Many operated with an independence that women wouldn’t see again for many decades.

No wonder, then, that sisters Margaret and Mary Brent stayed single. After establishing a 70-acre plot they called Sisters’ Freehold in the Colony of Maryland, Margaret became a businesswoman and money lender. When clients didn’t pay, she took them to court. In 1648, she went to the Maryland Assembly and demanded to be given a vote on a matter of some import to her fortunes. She was, we think, the first colonial woman to appear before a common law court and demand the vote, and she didn’t get it. Get ready for this to be a continuing trend.

That’s not to say these women didn’t play a role in political matters. As the main shoppers for their families, they were crucial to the boycotts that led up to the American Revolution. They shunned English tea, organized marches, sang political songs, and organized spinning bees. Abigail Adams, wife of Revolutionary leading light John Adams, said that women were ready to pick up muskets if need be. “If our Men are drawn off and we should be attacked,” she wrote, “you would find a Race of Amazons in America.” And women did fight: on the battlefront, as camp followers and spies. After all, they were as impacted by the results as anyone. But when it came to their role in the new nation’s politics, that’s something they seemed happy to forget. After all, Thomas Jefferson wrote to one politically-minded woman, “the tender breasts of ladies were not formed for political convulsion.” Bite me, TJ.

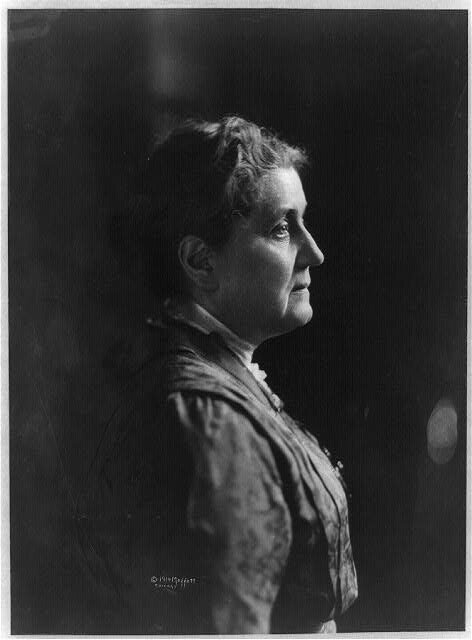

Abigail Adams, early advocate for women’s rights, female education, and the abolition of slavery. All around kind of a knockout.

Courtesy of Wikicommons..

In 1776, the Declaration of Independence said that “all MEN are created equal.” Though of course, by that, they meant only men, and really only white ones. That didn’t stop Abigail Adams from writing to her husband at the Continental Congress, knowing that important decisions about her sex were being made. “Remember the ladies,” she wrote--words that would echo hauntingly through the minds of many women for generations. “And be more generous and favorable to them than your ancestors. Do not put such unlimited power into the hands of the husbands...that your sex are naturally tyrannical is a truth so thoroughly established as to admit of no dispute. But such of you as wish to be happy willingly give up the harsh title of Master for the more tender and endearing one of Friend. Why then, not put it out of the power of the vicious and the Lawless to use with cruelty and indignity and impunity. Men of Sense in all Ages abhor those customs which treat us only as the vassals of your Sex.” His answer, I’m afraid, is going to make you want to trounce him soundly. “As to your extraordinary code of laws, I cannot but laugh.” He, like many, believed that women influenced society without needing any political power--they always had, hadn’t they? Their job was to morally influence their husbands and raise virtuous sons, and by doing so they helped create a fair nation. Come now, ladies. Let’s stay in our lane.

To vote at this time, you had to be a landowner. This knocked out pretty much everyone but white men. But then, sometimes women owned property: so what about that? Over time, laws were changed. By the turn of the 19th century, the only colony that allowed women to vote was New Jersey. Well, by “allowed,” I mean the law’s wording didn’t strictly prohibit it. So many women showed up at the polls that some worried that if nothing was done about it, “we may shortly expect to see them take the helm--of government.” We can’t have that! In 1807, after a right mess of an election, the New Jersey legislature decided to reform the law. They explicitly took voting rights away from women, and African Americans while they were at it. They wouldn’t get them back for many decades to come.

Many women continued to question this situation: Abigail Adams, poet Phyllis Weatley, the Southern Grimke sisters, who speak out against slavery and the limits placed on women. Sarah Grimke says in 1838:

“I ask no favors for my sex, all I ask of our brethren is, that they will take their feet from off our necks, and permit us to stand upright on that ground which God has designed us to occupy.”

But by the mid-1800s, little has changed for women in regards to their legal status. If anything, the Victorian era and its ideas about separate spheres have made it worse. Even Elizabeth Cady Stanton, an affluent, upper-class white woman, feels constricted by the limitations placed on women of her era. In a time when most women struggle to make a living wage on their own, marriage is often the clearest path to security. But once they marry, women are, in Stanton’s words, “civilly dead.” In her Declaration of Sentiments, delivered at the first national convention on women’s rights in 1848, Stanton will say that man “...has compelled her to submit to laws in the formation of which she had no voice…” Her husband votes FOR her: why would women need their own voice in government when the men in their lives, their protectors, can speak for them? As an essay from the 1790s puts it, marriage is a woman’s chance to “cheerfully submit to the government of their own chusing [sic]”. But what about unmarried women, abandoned women, enslaved women, divorced women, struggling women? Who is supposed to speak for them? As Susan B. Anthony, Stanton’s partner in leading the early suffrage movement, will one day say: “Woman must not depend upon the protection of man, but must be taught to protect herself.”

Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony become the dynamic duo who go on to form the National Woman Suffrage Association.

Courtesy of Library of Congress.

Having no voice in government can have ripple effects that can affect your day to day. Women can’t own property or make contracts in their own right. They can’t even keep their wages, if married - they hand them right over to the male head of their house. Most colleges and professions are off limits to them. After all, as Dr. Charles Meigs tells his gynecology students in 1847: “She has a head almost too small for intellect and just big enough for love.” Women’s medical and gynecological care is in the care of numbskulls like that guy. Men who thinks the womb makes women naturally more prone to going crazy. Just two years after he shares that gem with his students, Catherine Blackwell becomes the first woman to get a medical degree in America. She is inspired to make the move after a dying friend confesses that her whole ordeal would have been so much easier with a female doctor. How does she get into that college, you wonder, when women aren’t allowed to attend them? The faculty let the all-male student body vote on the issue, and they all vote “yes” - as a joke. Apparently they are pretty well shocked when she shows up on her first day of class.

Catherine is an exception, as is any woman who breaks into such a profession at this time, and she has to fight for it tooth and nail. Women can work, of course, but she’s likely to be paid a lot less for it. Teaching is still mostly a man’s profession, as most believe the role requires you to be strong enough to apply sound beatings. Civil War nurse, and so much more, Clara Barton’s first job was being a teacher. She once famously said that “I may sometimes be willing to teach for nothing, but if paid at all, I shall never do a man’s work for less than a man’s pay.” She opened her own successful school in New Jersey, and then the town hires a male principal while she’s on vacation, saying they’ll gladly keep her on as his assistant...at half his salary. Yeah, no thanks. But at least she had the option--at least she had a family with some money and social status to rely on. Many women are facing down limited job prospects. Jobs like that of a laundress, which will earn her 10 bucks a month at the most when most working men’s monthly salaries range from 10 to 20. A maid earns 4 to 7 dollars, while well-regarded cooks make 7 or 8. As a domestic servant, you have to live in someone’s house and potentially deal with sexual harassment. And if she gets pregnant, is the man likely to step in and help out? No way, lady. American society looks at perpetually unmarried women with both suspicion and pity. And unmarried women with babies...well. You might as well be a damned lady of the evening. Many hard working, working-class girls turn to sex work because their wages are so bad they have to side-hustle to make ends meet. This is more likely for single women, or those with a husband who can’t or won’t provide.

If a couple divorces, which is difficult and seriously taboo already, the husband is likely to get all of her possessions AND the children. AND if a husband decides his wife isn’t all there, he can stick her in a mental institution without needing her consent. Insane asylums become catch-alls for women who are violent, difficult, or just generally inconvenient. Husbands and fathers call on psychologists to check out their lady’s “abnormal” behavior: things like exhaustion, lack of menstruation, grieving too hard after a loved one dies, swearing, and of course masturbation. Epilepsy and a high sex drive are considered a kind of mania. In a list of intakes at Wisconsin’s Mendota Medical Asylum between 1869 and 1900 I found the following entry: a German woman, married, with eleven children, was checked and deemed “Insane by domestic troubles.” What mother of eleven ISN’T insane by domestic troubles?! But I digress.

Elizabeth Ware Packard is a walking advertisement for the dangers inherent to women in this century, especially when you’re married to someone who does NOT see you as his equal. This Illinois mother of six disagreed with her husband Theopholis, a Calvinist minister, on several issues: child rearing, money, slavery. But the real trouble comes when she starts questioning his religious beliefs. In 1860, he hires a doctor to have a chat with her while pretending to be a sewing machine salesman. After she complains about her husband’s domineering behavior, he diagnoses her as insane. She is, as she put it, “legally kidnapped,” and spends three years in an asylum before finally getting her case seen in court. “I regarded the principle of religious tolerance as the vital principle on which our government was based, and I in my ignorance supposed this right was protected to all American citizens,” she wrote later, “even to the wives of clergymen. But, alas! My own sad experience has taught me the danger of believing a lie on so vital a question.”

off i go to the loony bin…

A newspaper illustration featuring Elizabeth Ware Packard, Wikicommons.

Women of all classes have to deal with these issues, but some women are especially vulnerable. Poor and single women, immigrants, enslaved women and Native American women. If we catalogued all the ways that having no public voice hurt these populations, we’d be here for a very long time.

Many indigenous nations - the Iroquois, for one - had long exercised a far greater level of equality than in white settlement America. Most of their societies were matrilineal, meaning that descent and property was passed down through a woman’s line. They held important positions and a more equal division of labor. Many of the women in the wave of the suffrage movement were directly inspired by those communities. And even as they’re pushed west by settlers, told about all the rights they shouldn’t have, Native American women continue to speak up demanding justice. When Sarah Winnemucca, a Paiute woman, goes to Washington to speak out against the abuses being laid on her people, she says “If women could go into your Congress, I think justice would soon be done to the Indians.” True? We’ll never know, since women in this era aren’t allowed to run for office.

In 1840, Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Lucretia Mott meet at an Anti-Slavery Conference in England and bond over being denied the right to speak at it, given the fact that they’re women. They decide when they get home they’ll start organizing their OWN convention, specifically about women’s rights. Eight years later, they held what’s called the Seneca Falls convention. Stanton delivers her Declaration of Sentiments, saying that “Man has endeavored, in every way that he could, to destroy [woman’s] confidence in her own powers, to lessen her self-respect, and to make her willing to lead a dependent and abject life.” But, she felt, without the right to vote, all of their declarations would be nothing more than fanciful wishes. So she added this to the resolution: “That it is the duty of the women of this country to secure to themselves their sacred right to the elective franchise.”

A lot of the convention goers are horrified. “Oh, Lizzie!” Lucretia Mott cries upon hearing it. “If thou demands that, thou will make us ridiculous!” Demanding the vote is considered completely extreme and deeply unfeminine. They have so many other, more pressing things to fight for. For many, suffrage is a step too far. But women have been stepping out in other ways for a long time, using their voices to champion reform causes, most especially abolition.

For a long time, the fight for abolition and suffrage were deeply intermingled. Many abolitionists pushing for freedom also believed that women should have the same rights as men. Women like Stanton and her long-time suffrage compatriot, Susan B. Anthony, cut their reform movement teeth fighting for the abolishment of slavery. Women are gaining experience with campaigning, fundraising, petitioning, and speaking to crowds. Though, to be honest, many of the women who step up to the mic to say anything in this era are rudely booed and treated to some pretty crass comments. It isn’t seemly, after all, for a woman to speak in a public setting! Not even at abolition conventions, it seems.

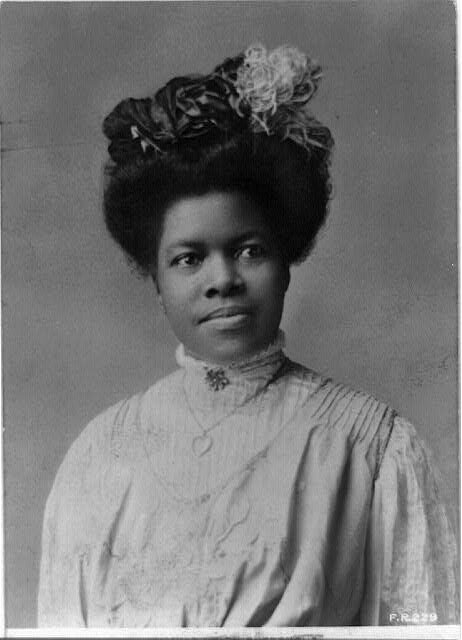

Even their symbology is similar: both movements use imagery of people bound in chains, and breaking free of them, to represent their bondage. Prominent abolitionist Frederick Douglas is all about it: not just women’s rights, but suffrage too. Sojourner Truth, an active abolitionist AND suffrage campaigner, is one of the most famous Black women to participate in the movement - though of course, not the only one. In 1851, at a women’s rights conference in Akron, Ohio, she delivered a speech about being Black and a woman in a country that seems to respect the rights of neither.

“I have as much muscle as any man, and can do as much work as any man.

I have plowed and reaped and husked and chopped and mowed, and can any man do more than that?

I have heard much about the sexes being equal; I can carry as much as any man, and can eat as much too, if I can get it. I am as strong as any man that is now.

As for intellect, all I can say is, if women have a pint and man a quart - why can’t she have her little pint full?”

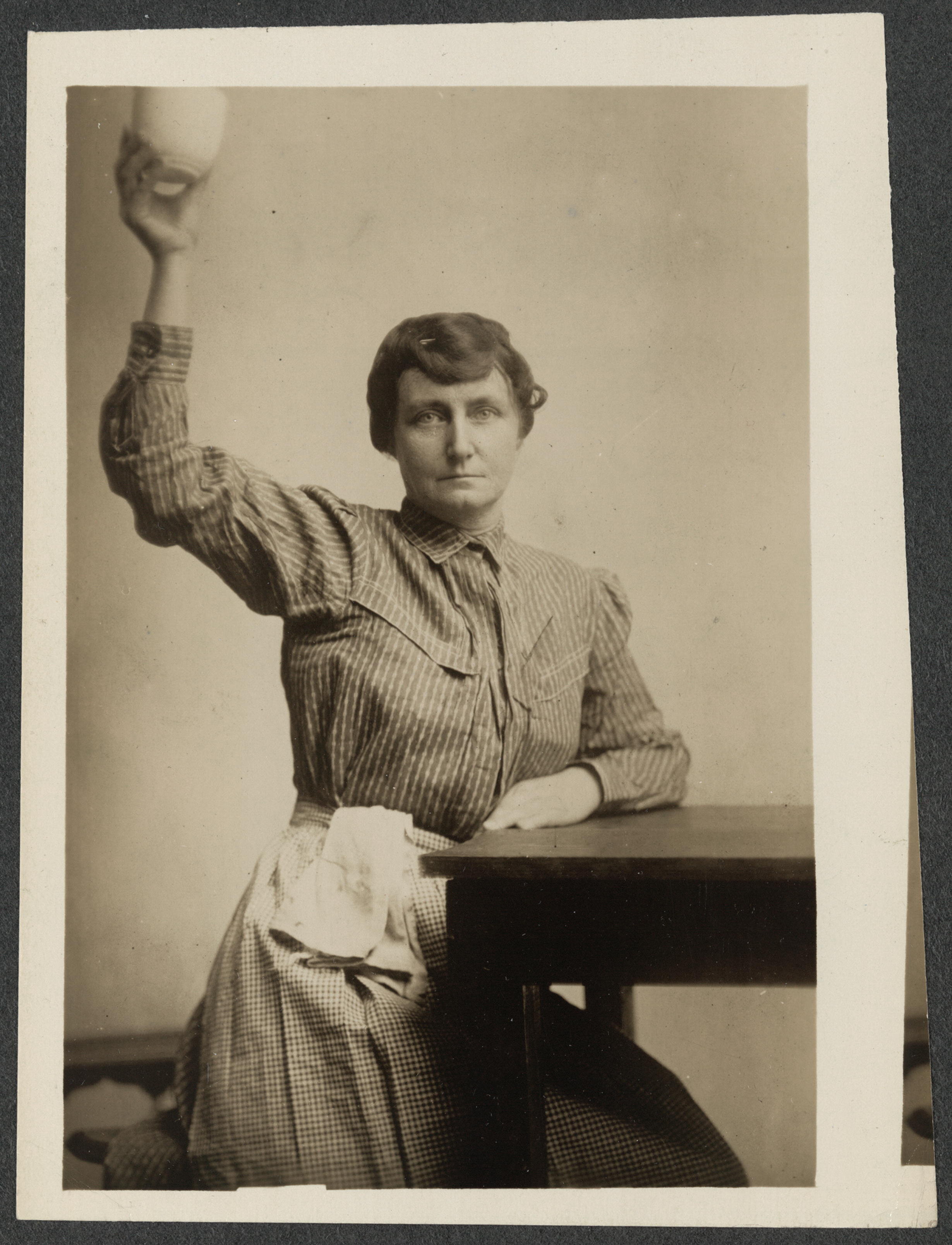

Sojourner Truth. Courtesy of the Library of Congress.

As the Civil War comes on, women push aside their fight for suffrage to pitch in for the war effort, and many risk their lives and reputations. They fight as soldiers, work as nurses - which is, at this time, ALSO a male-dominated field - and as campaigners and fundraisers. And then when it’s over, the nation is so grateful that they start piling on the legal rights? Not really. So suffragists have to figure out how best to take the cause up again.

In 1866, writer and lecturer Frances Ellen Watkins Harper stands up at the Eleventh National Women’s Rights Convention and tells the crowd about her experiences as a Black woman in America. When her husband died, all their property was taken from her. The mostly white audience nodded along: same old story. But then she tells them how she suffers under a double yoke of injustice; how her rights as a woman and as a Black person can’t be separated. To be successful, the causes needed to stay joined. She says, “We are all bound up together in one great bundle of humanity.” And so they form the American Equal Rights Association, dedicated to achieving suffrage for all.

But things get sticky when the discussion turns to the 14th Amendment and whether to support the draft of the 15th. The 14th prohibits states from denying eligible voters, but specified that they had to be male. The proposed 15th Amendment talked about not denying rights along the lines of “race, color, or previous condition of servitude,” but didn’t mention women. Where were they? Many suffragists throw their weight behind it anyway, feeling that emancipation for black men has to come first. Once they win it, surely they’ll reach back and pull up the women who’ve fought beside them? But some, like Stanton and Anthony, felt that this wording is a betrayal. Stanton, a long-time abolitionist, gives an angry speech in which she basically says something like, ‘you’re going to give the vote to people of color and foreigners, but not educated white women?’ Not good. There are plenty of women of color working hard for suffrage. But the mainstream suffrage organizations don’t seem able or willing to address the everyday challenges Black women face. There’s a lot more to say and explore about this issue, but suffice it to say that this movement isn’t free of racism or classism. It’s a shadow that will forever hang over the cause.

And so the suffrage movement fractures. Stanton and Anthony split off, starting the National Woman Suffrage Association, a more radical group all for universal suffrage by means of the constitution. Others, like Lucy Stone and Julia Ward Howe, form the American Woman Suffrage Association, which actively champions Black men’s suffrage and want to push for women’s suffrage state by state. They won’t merge until 1890, forming The National American Woman Suffrage Association. And universal suffrage is still a long way away.

Still, there ARE places where a woman can cast her vote. As settlers start moving West and establishing territories, they take a more liberal approach to the issue, hoping to lure women out to the predominantly man-filled settlement west. It’s not like there are enough ladies out here on the plains to make THAT big a difference: why not throw them a bone? In the late 1860s, by a vote of 13-6, Wyoming passes a bill giving women the right to vote and hold office. And when they apply for statehood and the federal government balks, they snap back, “We will remain out of the Union a hundred years, rather than come in without our women.” On September 6, 1870, a posse of ladies led by a 70-year-old housewife marched to the polls in Laramie, making them some of the first in the U.S. to vote in a very long time. Of course, the West is less kind to its indigenous residents. In 1876 the Supreme Court rules that no Native Americans can vote, because technically they aren’t citizens. That, of course, includes women.

An illustration from Puck magazine showing Lady Liberty standing over the Western states that had given women the vote already, lighting the path for the rest of America. Or trying to. Courtesy of the Library of Congress.

But hold up. When the 14th Amendment is ratified in 1868, it grants citizenship to “all persons born or naturalized in the United States.” And citizenship should include the right to vote, shouldn’t it? Hundreds of women showed up at the polls to test the point, including Sojourner Truth and Susan B. Anthony. “Well I have been & gone & done it!!” Anthony writes to a friend on November 5, 1872. She was sure they wouldn’t let her vote: she kind of hoped for it, actually, so she’d have grounds for a lawsuit. Two weeks later, she is arrested by a federal officer, but it doesn’t give her grounds for taking it to court. Down in St. Louis, though, when Virginia Minor is turned away at the polls, the suffrage leader in her state sues the election official—well, her husband sues him, because legally she can’t. Minor v. Happersett gets all the way to the Supreme Court, where they argue that Missouri violated the 14th Amendment by denying her privileges as a citizen. The ruling? That “the Constitution of the United States does not confer the right of suffrage upon anyone.” It set a precedent for state-by-state voter suppression. For the movement, it is a real momentum-stealing blow.

Rights for women do start gaining ground on a state-by-state level. Back in 1850, Tennessee became the first state to explicitly outlaw wife beating. Hooray!!* (*yes, that was sarcasm). We start seeing things like married women gaining separate economy, owning AND controlling property, and being granted patent rights. From what I can glean, almost all of these rights were for married women - not single ones. Heaven forfend a single lady have any control over things.

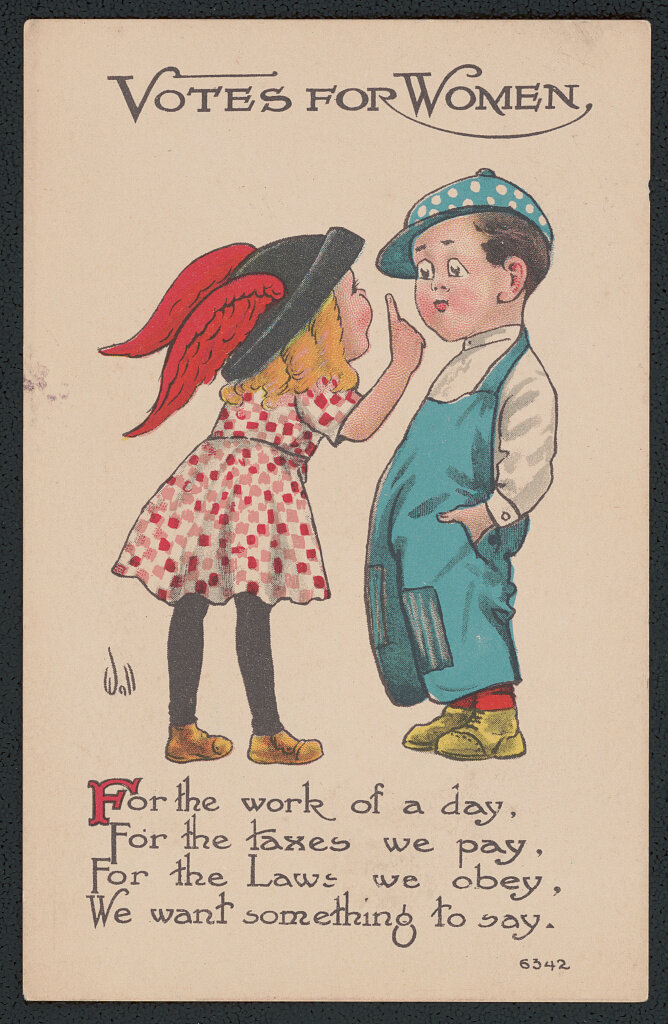

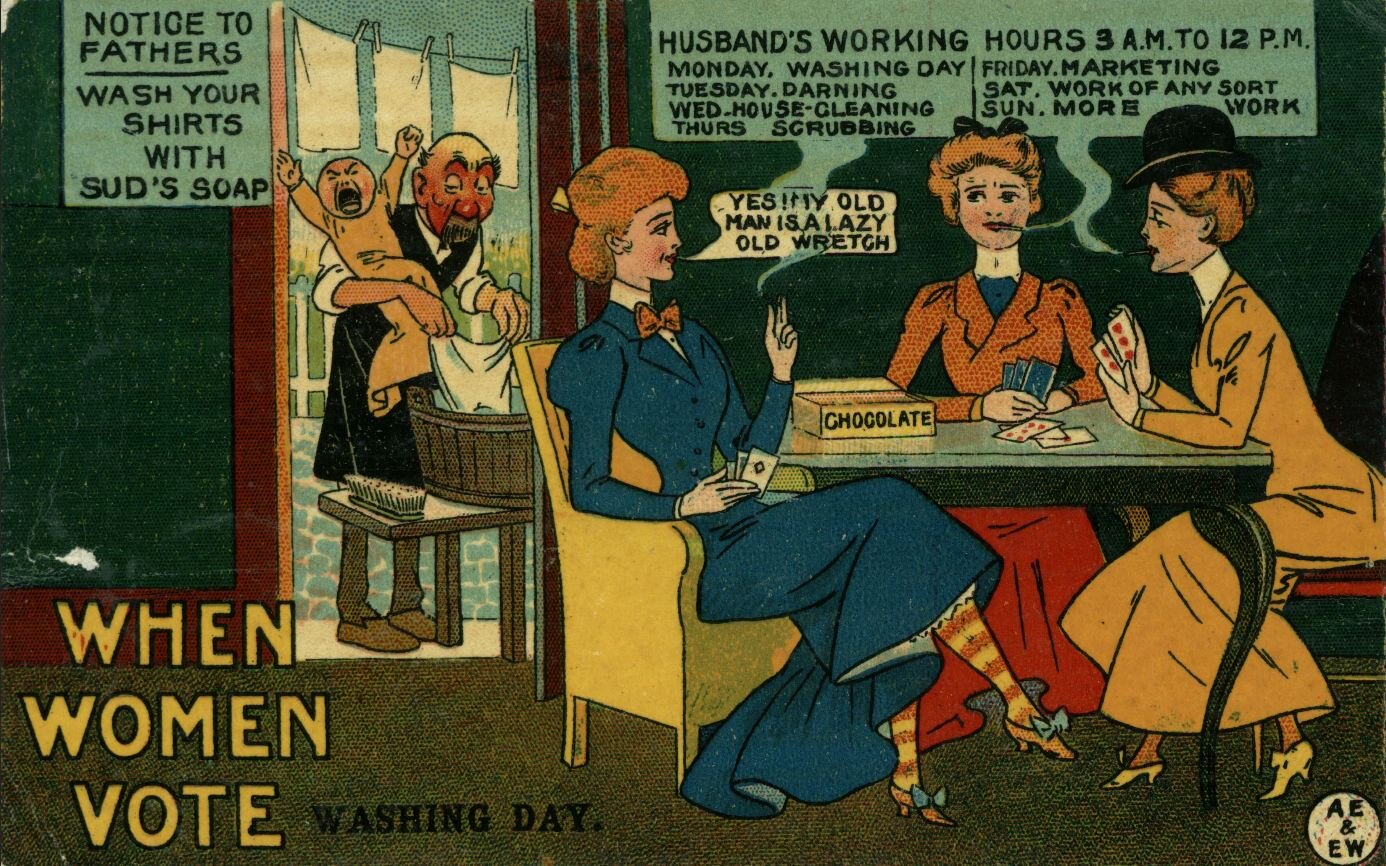

Suffrage, though, was another matter. The Woman Suffrage Amendment was introduced in 1878, but it’ll take another forty years to actually get anywhere. There are things like the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882, which says that no Chinese immigrant can become citizens, and therefore can’t vote. And all along the way, there are plenty of haters actively campaigning AGAINST female suffrage, making the fight feel like pushing mud uphill. In 1871 the Anti-Suffrage Party pops up, as do anti-suffrage postcards showing scenes like a man doing the washing while holding the baby while their wife sits with her friends and smokes. Horrors! Here’s another haunting fact: a lot of these campaigns were run by women. Mrs. General William Tecumseh Sherman and Mrs. Admiral John A. Dahlgren went to Congress, warning that suffragists’ “illusive new doctrine” would upset the American family dynamic. They didn’t want to be saddled with the vote, they said: it would lead to competition with men, would disrupt their moral purity, and actually take some of their influence away. Pamphlets popped up, one saying that the pro-suffrage movement was being perpetrated by “a small body of intensive and fanatical women” and that giving women the vote “would be detrimental to the best interests of the State.” Another advised its female readers that they “do not need a ballot to clean out your sink spout…Control of the temper makes a happier home than control of elections.” Oh my. This is a hard argument for many of us to understand: why campaign against yourself? The answer is, of course: it’s complicated. We’ve seen time and again on this podcast, in our stories about women in different eras, that there are many kinds of power, and many ways to wield it. Some women thought theirs was most potent when worked from behind gauzy curtains and on the home front. It made the fight for suffrage a whole lot harder.

The first dozen states to grant the vote to women are in the West. Colorado boards the train in 1893, Utah and Idaho in 1896, Washington in 1910, California in 1911, Oregon, Kansas, and Arizona in 1912, Montana and Nevada just before World War I. And yet at this point, it seems almost impossible to get universal suffrage. “It is to the strong, courageous, and progressive men of the western States that the women of this whole country are looking for deliverance…” wrote Ida Husted Harper in 1905. “It is these men who must start this movement and give it such momentum that it will roll irresistibly on to the very shores of the Atlantic Ocean.” But it’s the women who have to fight tooth and nail for it, and do it moving state by state. A painful process. Not to say they don’t run for office anyway. Suffragist and newspaper publisher Victoria Woodhull is the first woman to run for president in 1872, under the banner of the Equal Rights Party. Okay, so she is only 33 and so isn’t officially eligible, and she names Frederick Douglass her VP without asking permission, but...this racy dame has a point to make. “If Congress refuse to listen and to grant what women ask,” she once tells the House judiciary committee, “there is but one course left to pursue. What is there left for women to do but to become the mothers of the future government?” Belva Lockwood is the first woman to run a super-legit run for president, in 1884 and 1888. At least 11 other women have run for president or vice in America’s history. A few of them did it before women could vote.

THE NEW GENERATION

And so we enter the turn of the century and what’s called the Progressive Era. It’s a time when life for women in America is changing fast. They are starting to cast off their corsets and embrace fashion that is easier to move in, especially so they can ride the new-fangled bicycle. After years of heavy skirts and small steps, they can whip through the park on their two-wheeled contraption. “The bicycle,” Susan B. Anthony says, “did more to emancipate women than anything else in the world.” They become a symbol of what was called the “New Woman.” She’s more independent, more liberated, than ever. She has legs, and she isn’t afraid to show them, dammit! A Scribners essayist said at the time that the bicycle has “given to all American womankind the liberty of dress for which reformers have been sighing for generations.” Others worry the bike was creating loose morals. After all, said the Boston Rescue League, some 30% of the sex workers who came to them for aid said they’d been bike riders at some point.

And while they may not be able to cast their ballot, many women are taking up serious reform initiatives, working to clean up their world and make it a fairer, more moral place. They’re starting unions, fighting for temperance, creating low income housing and education, especially for women. Jane Addams is pioneering the settlement house movement, becoming a well-known campaigner for better living conditions for the downtrodden. There are women working in male-dominated fields, like Ida Tarbell, the investigative journalist who rips into big-time monopolists like John D. Rockefeller. Female entrepreneurs are making big money, like C.J. Walker, a hair product tycoon.

So what is the deal - why don’t women have the vote? Because progress isn’t a smooth, steady escalator ride, even if we like to think it is. It’s a mountain climb with switchbacks and stumbles - a jagged and often complicated path. And there’s another root to the issue: fear about what women will DO with their vote. The Democrats fear they’ll vote Republican. The robber barons worry they’ll vote to break up monopolies and lean down hard about social reforms. Liquor companies pour money into anti-suffrage campaigns because they think women will vote for Prohibition, killing business. They know that a woman’s voice can be a powerful thing.

The suffrage movement is in something of a slump now, dispirited, tired of moving state by state, working tirelessly, and winning rights at a gruelling crawl. Vets like E.C. Stanton no longer think they’ll see the vote in their lifetime. “Our movement is belated,” she said at age 86. “And like all things too long postponed, now gets on everybody’s nerves.” Even Carrie Chapman Catt, who took over from Anthony as leader of the National American Woman Suffrage Association, said that she wasn’t sure she had it in her to get them there. But she knew that there was a woman out there who would. “Some day she’ll come,” she wrote to a friend in 1912: the woman who would finally get them across that illusive finish line. “Perhaps she is growing up now…” They are already grown, it turns out, and many are ready to take the movement to the next, militant level.

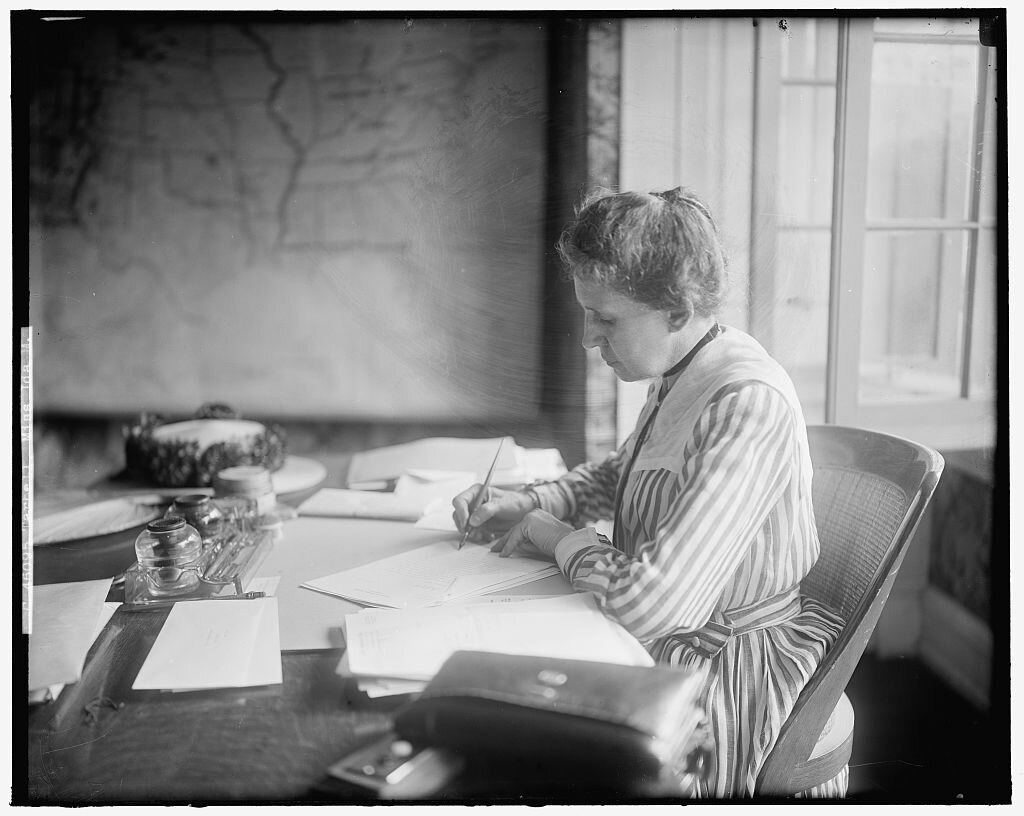

Don’t let their relaxed vibes fool you. Carrie Chapman Catt and Helen Gardener are working hard for the suffrage cause.

Courtesy of the Library of Congress.

CLENCHED FISTS AND SILENT SENTINELS

We’re in 1913, now, the year Woodrow Wilson takes office. He has never been a friend to women’s suffrage. As a professor at Bryn Mawr, he thought it was beneath him to have to teach female students. He once said that woman suffrage was “the foundation of evil in this country.”

Enter Alice Paul, Lucy Burns, and E.C. Stanton’s daughter, Harriot Stanton Blatch. They all spent time in England, getting involved in the suffrage movement across the pond, which had a very different flavor. They saw firsthand how public marches and more aggressive tactics made a massive difference. These ladies threw rocks, threw themselves in front of carriages, and weren’t afraid to get themselves arrested. And then they get back to America to find the same old movement, the same old tired tactics. They are tired of being polite and asking sweetly. What Americans need, they decide, is a hard shot in the arm. So they start organizing rallies and marches, pageants and demonstrations. A march in Manhattan involved 10,000 people, all marching in the movement’s signature yellow. And it’s not just socialites: this new wave of suffragists want women from every walk of life involved and invested. Corset makers and nurses walk arm and arm with famous society women like Alva Belmont. There’s also Mabel Ping-Hua Lee, a Chinese immigrant who rides on horseback through the city, even though she knows the Chinese Exclusion Act will keep the right to vote denied to her. She fights for women’s rights just the same.

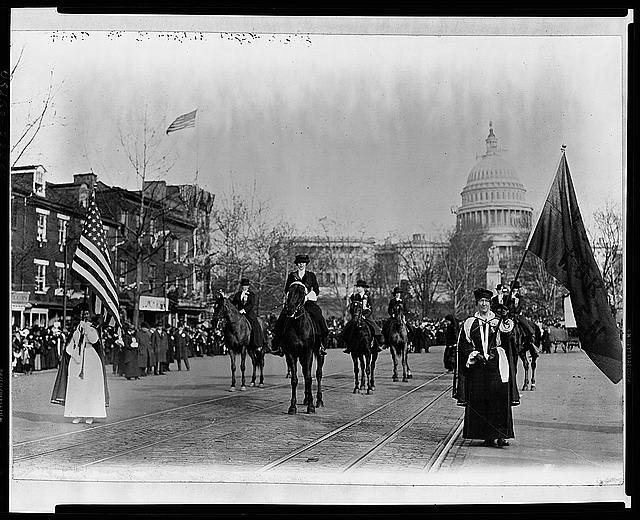

In 1913, they mobilize at least 5,000 women - some sources say up to 10,000 - to march on Washington the day before Woodrow Wilson’s inauguration. Let him SEE the population he’s saying shouldn’t have a voice in government. “this is the most conspicuous and important demonstration that has ever been attempted by suffragists in this country,” urged the NAWSA’s New York Headquarters. “...this parade will be taken to indicate the importance of the suffrage movement.” Women hear the call, charging ON FOOT from New York City for it, picking up suffragists as they go. The parade is led by lawyer Inez Milholland, all wrapped up in a white cape atop a prancing white horse. Now that’s making an entrance.

Inez Milholland. Courtesy of Library of Congress

But this is another complex, and sometimes haunting moment. Alice Paul wants the support of southern women, which means shoving Black suffragists to the back of the parade. Ida B. Wells, a prominent journalist and civil rights leader who spoke out against lynching in the South, refused to do so. She walked out of the crowd and into her state’s portion of the parade line, defying anyone to stop her. “If the Illinois women do not take a stand now in this great democratic parade, then the colored women are lost.” But they were lost: at least their images were. There were plenty of women of color in this parade, and campaigning around it. Prominent campaigner Nannie Helen Burroughs, for one, who said that “When the ballot is put into the hands of the American woman the world is going to get a correct estimate of the Negro woman.” You don’t see them as often in pictures because they were shoved aside, almost hidden. Another painful shadow in the fight for women’s rights.

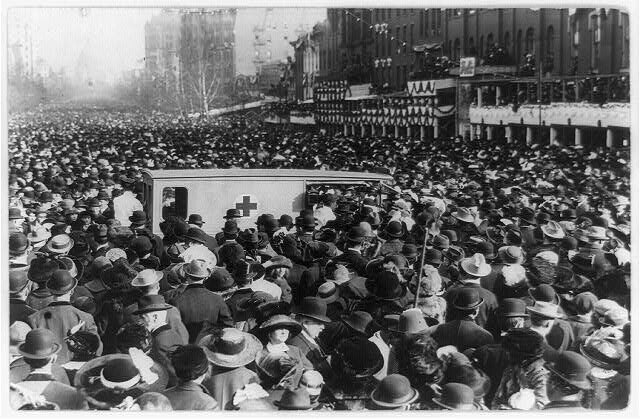

All the women suffer as they march, abuse hurled from hostile men lining the sidewalk. They are tripped, grabbed, shoved, and subjected to what one writer called “barnyard conversation.” The police are hopeless: sometimes they even join in. More than a hundred women are hospitalized. Ambulances come and go, always impeded and sometimes stopped, so that doctors have to fight their way to the injured. Later, the superintendent of D.C. police will lose his job over it. But the worst thing, besides calls of things like “Where are your skirts?” is how their antagonists treat it like a joke - something to be laughed at. But to these women, the issue is life and death.

The march infuses the movement with much-needed attention and energy, bringing more people to the cause. And yet they continue to struggle to make any real progress. The Great War has started over in Europe, and the nation’s mind is turned toward whether it should join the fray.

It’s 1917 now, and Woodrow Wilson has just been voted in for a second term. For four years, he’s ignored them, and when he had to take their meetings, he told them he had more important matters to attend to. A year ago he made noises about how he was starting to come around, but he still wouldn’t commit to anything; best for states to decide such things on an individual basis. More moderate suffragists are hopeful. Super militants like Alice Paul are not. AND he’s just signed off on America joining a war that’s supposed to be about fighting for democracy: a government in which 50% of its population can’t truly participate and inequality is rampant. In 1916, Montana suffragist Jeannette Rankin was elected to the U.S. House of Representatives: the first woman to win a seat in the federal Congress. So a woman can serve, but she still can’t vote! And when she speaks out against America joining the war, her male compatriots and the press all shout that it’s proof that women just can't handle either violence or the tough decisions. This is a war in which women will participate, fighting, as they always do, as ambulance drivers and nurses, tending victims of the 1918 influenza. 300 women — nicknamed “Marinettes” — will take on jobs at Marine Corps headquarters to replace the men who usually did them. They’ll take up positions on the home front, like train drivers and factory workers - the government’s clammoring for them to do them, even though they weren’t considered appropriate for women before. Opha May Johnson will become the first woman sworn into the Marine Corps. In other words, women can serve and suffer, but they still can’t have a say.

On January 9, women crowd into the new headquarters of the Congressional Union for Woman Suffrage. They’ve gathered in Cameron House, just a stone’s throw from the White House. Harriot Stanton Blatch stands up to address them. Her mother was once one of the biggest players of the suffrage movement, but what she has to say now would make even her mother blanch.

“We have got to bring to the President,” Harriot Stanton Blatch says to them, “day by day, week in, week out, the idea that great numbers of women want to be free, will be free, and want to know what he is going to do about it.” They’ve told us to sit down and be quiet - they’ve told us that we’re better when we’re seen and not heard. So why not turn that silence against them, making it into a form of protest? She asks them, “Will you not be a ‘silent sentinel’ of liberty and self-government?”

The women clustered together in Cameron House are officially over it. They decide it’s time to take the gloves off. On January 10, 1917, a bunch of ladies put on their hats and coats and went to stand in front of the White House. Their mandate is not to let anyone rattle them, or make eye contact with any angry passersby. They’re to be silent, holding their signs in front and pressing their backs to the iron gate for their safety. Alice Paul says they’ll be standing there, silently and peacefully, from 10-6 every day but Sunday for the foreseeable future.

Some find it an exhilarating bonding experience. Others, like Doris Stevens say, “anything but standing at the President’s gate would be more diverting,” and explained that she spent a lot of time wondering “when will that woman come to relieve me.” Sometimes truly exhausting. Some described how the sockets of their arms ache[d] from holding their signs, which say things like “MR. PRESIDENT, WHAT WILL YOU DO FOR WOMEN’S SUFFRAGE?” and “HOW LONG MUST WOMEN WAIT FOR LIBERTY?”

Woodrow Wilson just smiles and waves, even offering to have them into the big house for coffee if they’d like some. But he must be shaken: such a thing has NEVER happened in front of the White House. And he’s not the only one. Even some suffragists thinks Alice Paul’s gone way too far this time. Carrie Chapman Catt publicly denounced it. The National Association Opposed to Woman Suffrage said “As an argument it ranks with the small boy’s thrusting out his tongue. As a demonstration of fitness for the vote it is idiotic.”

Many people, even some suffragists, thinks it’s a bit much to picket, especially during wartime. But there is something about these silent women, standing there with the signs held high, through snow and rain and freezing wind. As the war rages on, their presence starts to wear away against the hardened. One congressman said there was “something religious” about it. Something almost holy. But in some corners, there is only growing animosity. When the chief of police warns that arrests are imminent if they don’t give up already, Paul says, “I feel that we will continue.”

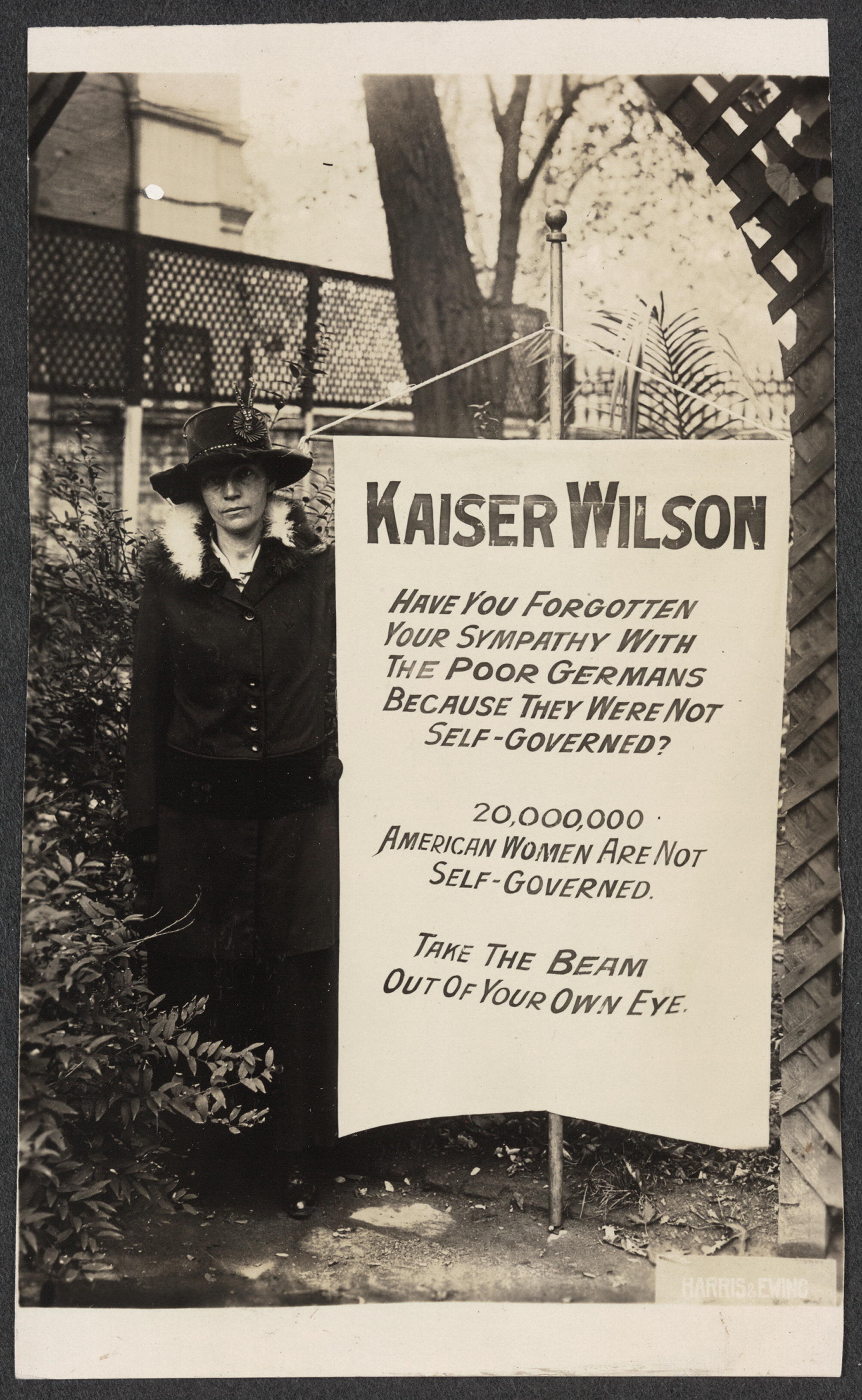

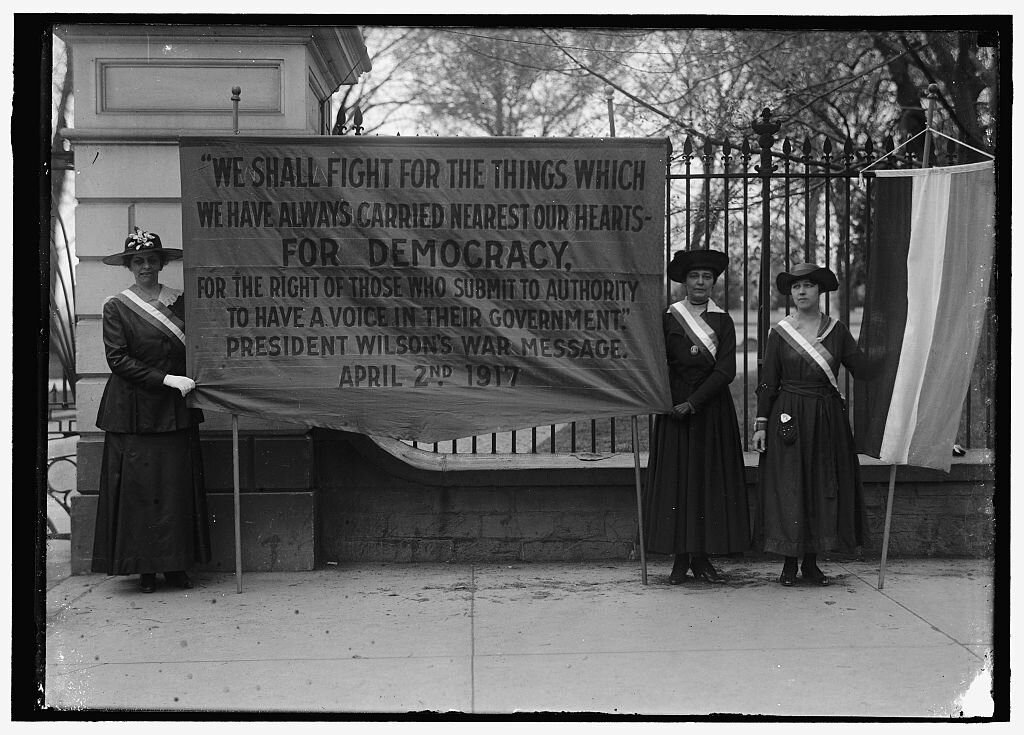

Things get less holy when a Russian delegation comes to visit the White House in June on 1917. Lucy Burns and several Sentinels unfurl a huge banner addressed to the envoys, comparing Wilson to the German kaiser for denying women the vote. It is pure scandal, and it inflames a riot. Angry bystanders rush in, pushing and ripping. The women refuse to back down. Suffragist Inez Haynes Irwin describes the “slow growth of the crowds; the circle of little boys who gathered about...first, spitting at them, calling them names, making personal comments; then the gathering of gangs of young hoodlums who encourage the boys to further insults...Sometimes the crowd would edge nearer and nearer, until there was but a foot of smothering, terror-fraught space between them and the pickets.” Days later, they hold up a sign etched with Wilson’s own words to Congress months before: “WE SHALL FIGHT FOR THE THINGS WHICH WE HAVE ALWAYS CARRIED NEAREST OUR HEARTS—FOR DEMOCRACY, FOR THE RIGHT OF THOSE WHO SUBMIT TO AUTHORITY TO HAVE A VOICE IN THEIR GOVERNMENT.” Remember the Ladies indeed.

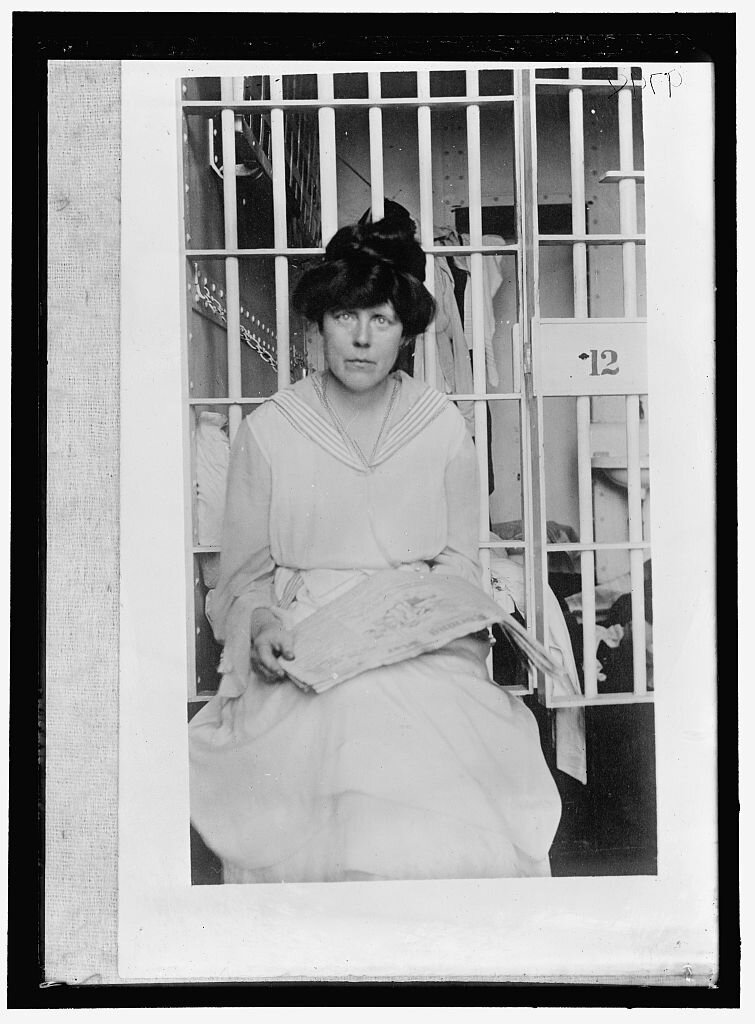

The police can’t arrest the women for standing there with signs - they aren’t breaking any laws. But soon enough, they start arresting them for things like blocking traffic. The establishment doesn’t want them arrested, turning them into matyrs. But fines and trips to the police station don’t work. So more and more women get sent to Virginia’s Occoquan Workhouse. The conditions are bad, the food is inedible, and they have very little contact with the outside world. One John Hopkins goes to visit his wife there and is so appalled that he confronts Wilson directly. Under pressure, Wilson tries to pardon the women, who won’t accept it. They didn’t break any laws. So they actually get kicked out of their prison.

And yet they just go on protesting, even as the violence grows worse. Imagine walking down the wide, bright streets of the nation’s capital, holding a sign asking your president for the vote. Imagine, then, being shouted at, then pushed, then hit, then dragged down that street. It happened, over and over. By the end of September, some two dozen women are being held at the workhouse. In October, so is Alice Paul. “I am being imprisoned” she told reporters, “. . . because I pointed out to President Wilson the fact that he was obstructing the cause of democracy and justice at home, while Americans fight for it abroad.” She says she should be treated as a political prisoner. She’ll be treated as a prisoner, that’s for certain.

Their cells at Occoquan are dark and dank and cramped. Rats scamper through the corners. Bedding goes unwashed for weeks and months. Worms wriggle through their meager, inedible food. At one point the suffragists collect them all from their bowls of soup and offer them up to the warden on a single spoon. Enjoy!

In October, Alice Paul is serving six months in this nightmare, and she decides it’s time to go on hunger strike. Some doctors examine her and try to change her mind. She won’t, so they force feed her. Every day, sometimes multiple times, they take her to the psych ward and strap her to a chair. She will suffer from the aftermath for the rest of her life.

And not just her. On November 14, 1917, women are arrested on what becomes known as the “Night of Terror.” They are dragged down the halls, then bodily tossed into their cells. 55-year-old Dora Lewis hits her head against a wall and drops to the floor, unmoving. One woman will have a heart attack and no doctor will be brought to attend to her. Lucy Burns, whom the Washington Post said her guards called “worth her weight in wild cats,” fought her guards all the way. When Burns called the roll to make sure all the ladies are all right, the guards threaten to put them all in straightjackets. Burns keeps talking, and so they cuff her wrists and say they’re going to put a gag buckle in her mouth if she won’t stop. One is even thrown in with a bunch of male prisoners and told they can do whatever they want with her.

That night they’re brought no food, no water. There is no private place to change or to relieve themselves. “The water closets were in full view of the corridor where Superintendent Whittaker and the guards were moving about,” wrote Mrs. John Winters Brannan. “The flushing of these closets could only be done from the corridor, and we were forced to ask the guards to do this for us,—the men who had shortly before attacked us.”

Mrs. Virginia Bovee, a prison matron, who is let go because she shows kindness to the inmates, swore that: “Prisoners are punished by being put on bread or water, or by being beaten. I know of one girl who has been kept seventeen days on only water this month...The same was kept nineteen days on water last year because she beat Superintendent Whittaker when he tried to beat her.” She speaks of beatings, too, doled out by the superintendent and his son. “I know of one girl beaten until the blood had to be scrubbed from her clothing…” 16 of them go on hunger strike and, like Paul, many are force-fed. And they are isolated from each other, told that everyone else has already given in. Imagine enduring such torture - because this is torture - and having to do it all alone.

The press say the women are being treated just fine. “Don’t let them tell you we take this well,” wrote Rose Winslow, who found a way to smuggle her messages out. “Miss Paul vomits much...we think of the coming feeding all day. It is horrible.” When word gets out, the public is outraged at their treatment. Suffragists picket outside the White House, this time for the suffragists’ freedom. Wilson is forced to change his stance. The women are let go, and their suffering, it turns out, helped to gallify the nation. In 1919, the Susan B. Anthony Amendment finally gets congressional approval. But it has to be ratified by 36 states. In the summer of 1920, it’s so close suffragists can taste it. The drama comes to a head in Tennessee. The press call it the War of the Roses as supporters wear yellow roses in their lapels, and opponents red. The flower count is so evenly split that everyone’s holding their breaths, waiting to see what will happen. The speaker, who’d long been a suffrage supporter, suddenly does an about face. But then along comes red-rose-wearing 24-year-old Harry Burn. Everyone thinks he’s going to go against suffrage, but they don’t know that he’s got a fresh letter from his mom tucked in his jacket. “Hurrah and vote for suffrage,” Febb Burn wrote her son. “Don’t forget to be a good boy.” And he’s a boy who listens to his mama.

The 19th Amendment, which says that no citizen can be denied the right to vote based on their sex, becomes law on August 26, 1920. In November of that year, Charlotte Woodward - who went to the Seneca Falls convention as a young girl - cast her ballot. She is the only woman from that era who gets to see this dream become reality.

Throughout the land, there is much celebration. And yet, in this, not every voice is heard, and it doesn’t make everything right. The 19th Amendment only says what states CAN’T do: deny someone a vote on the basis of sex. But they CAN impose poll taxes, literacy tests, and other forms of voter suppression on women of color to keep them from voting. Asian Americans aren’t allowed to qualify as citizens. Native Americans won’t be given the right to vote in some states for decades more to come. To go to the polls, these women risk violence and intimidation. Some registrars refuse to process the papers or handed them a blank sheet of paper. Gagged and silenced once again.

But women kept fighting - for their right to speak, to be safe, to be heard. They keep fighting. The suffragists understood that representation matters. To vote is a right that everyone deserves, but it’s also a privilege. So go and vote, honoring all the women who raised their voices so that we can exercise our right to do the same.

MUSIC

The Chamber and Darkest Child by Kevin MacLeod (incompetech.com). Licensed under Creative Commons: By Attribution 3.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/). All other music licensed from Storyblocks.com.

VOICES

Elizabeth Cady Stanton = Ann Wand

Susan B. Anthony = Christina Capriola

Sojourner Truth = Veronica C. R. Washington-Ramos

Mrs. John Wnters Brannan = Angela Catrickes

Frances Ellen Watkins Harper = Christa Taubert

Abigail Adams and Clara Barton = Nancy Wassner

Rose Winslow = Katie Conrad

Elizabeth Ware Packard = Cecilia Cackley

Lucretia Mott = Sara Stockwell

Alice Paul = Dee Robinson

Carrie Chapman Catt = Sierra Marcum

Ida Husted Harper = Tasha Schroeder

Victoria Woodhull = Katy from Queens Podcast

Harriet Stanton Blatch = Iris Strauss

Doris Stevens = Brittney

Mrs. Virginia Bovee = Annie

Inez Haynes Irwin = Diana Larson

Febb Burn = Edie Chevalier

Presidential men = John Armstrong

Signs and pamphlets:

Patricia Thacker

Julia Fuchs

Lauren Oakes

Madelyn

Iris Strauss