That Girl is Poison: A Partial History of Women and Toxic Things

They say that poison is a woman’s weapon of choice.

But these days, it isn’t a very popular weapon. A Washington Post article used the FBI’s Supplemental Homicide Report to show that way more men commit murder than women, and poison is the sixth most common way for a woman to kill. But still, there is this pervasive connection between women and poison: that silent killer that doesn’t require brute strength, but a devious and, some say, womanly cunning. When mysterious deaths happen, it’s often blamed on women and their lethal concoctions: rat poison in the pie, arsenic in the wine. And sometimes that’s what really happened.

But plenty of women from history have been poisoned, too. They flirted with death every day, even if they didn’t know it, dousing themselves in dangerous cosmetics and hair products; wrapping themselves in poisonous clothing, caving to the pressure to look young and beautiful, only to have it be the death of them.

Grab a mortar and pestle, a unicorn horn, and some bright green silk. Let’s go traveling.

***

RESEARCH SOURCES

BOOKS

To learn more about poison in the Renaissance period, and how modern forensics has helped us figure out what killed royals of the past, check out The Royal Art of Poison by Eleanor Herman.

If you’re interested in deadly fashions, go for Fashion Victims: The Dangers of Dress Past and Present by Alison Matthews David

For a more specific deep dive, Bitten by Witch Fever: Wallpaper & Arsenic in the Victorian Home by Lucinda Hawksley. I haven’t done anything like justice to the story of the Radium Girls, and it is one that is very much worth exploring in greater detail.

I encourage you to pick up Kate Moore’s book The Radium Girls, which is one of the best and most powerful nonfiction books I’ve read in the past few years.

podcasts

“Locusta the Poisoner” by Ancient History Fangirl. A great dive into the lady herself AND the things Romans used to poison each other!

ONLINE

“The Arsenic Dress: How Poisonous Green Pugments Terrorized Victorian Fashion” by Alison Matthews David. Jezabel, Nov. 2015.

“Poisons and Poisoning Among the Romans” by David B. Kaufman. Digitized from Classical Philology Vol. 27, No. 2 (Apr. 1932), pp 156‑167

“The History of Green Dye is a History of Death” by Jennifer Wright, Racked.com, March 2017.

“Arsenic and Old Tastes Made Victorian Wallpaper Deadly” by Kat Eschner, Smithsonian.com, April 2017.

“Poisonous Pigments: Scheele’s Green.” Los Angeles Art College, 2018.

“Deathly décor: a short history of arsenic poisoning in the nineteenth century.” Halsam, JC. Res Medica 2013, 21(1), pp.76-81 (PDF online)

“A History of Women Who Burned to Death in Flammable Dresses” by Rae Nudson, Dec. 2017.

For more on modern cosmetics and how to keep yourself tox-free:

EWG’s Skin Deep website. This is a great place to find out what ingredients you should avoid and what to look for in a ‘toxin free’ body product. It also lets you look up all the individual products currently in your cupboard and see how they rate, which makes it all much easier.

Safe Cosmetics Australia: a good source for all of my people Down Under.

A clean beauty monthly subscription service! Sounds like a winner, though I haven’t tried it myself.

A RECIPE FOR TOX-FREE COFFEE CHOCOLATE SCRUB BARS:

I’ve made these a few times and really enjoy them. An indulgence that you could probably eat if you wanted to!

Makes approx. 16 x 30 ml (1 fl oz) bars

250 g (9 oz) organic cacao butter, grated or finely chopped

90 g (3 oz/3/4 cup) coffee grounds, espresso grind (you can use fresh or used, but if used make sure to dry them out in the oven first)

10 drops lavender essential oil (or whatever you like: I used grapefruit)

In a double boiler, gently melt the cacao butter over a low heat until melted. Allow it to cool to room temperature. Add the coffee grounds and essential oil and stir well. Pour the mixture into the moulds, then place them in the freezer for a minimum of 1 hour to set. If you live in a warm climate, store any extra bars in an airtight container in the refrigerator to avoid them melting. Even in my relatively cool climate, I’ve found they are prone to mold if left too long in the bathroom, so refrigeration might be the way to go.

To use: Gently massage the bar over damp skin, avoiding your face and neck. Rinse well and pat dry. This is going to make your shower a bit slippery, so be careful when you get out.

Poison has a long and interesting history that goes way back to the ancient world. We start in Rome, 54 CE. A woman sits in a prison cell, watching the flame from the wall sconces glow. She is a prisoner now, awaiting judgement. But around gilded tables in the highest circles, she’s notorious: a sorceress, a poisoner…an artist, they say, and her medium is death. Many have acquired her services and paid top dollar for it, turning to her, as Tacitus has it, “to serve the purposes of dark ambition.”

In Rome’s imperial palace, an empress is pacing, trying to decide how to kill her husband. Because she’s determined that her son Nero will be emperor, and her husband is starting to threaten her designs. Agrippina the Younger knows she can’t poison him in an obvious way: she doesn’t want him to know what’s happening until it’s far too late to stop it. And so she goes to that woman in the cell, Locusta, and makes a proposition that she surely won’t refuse. Make me a poison to suit my needs, she demands, and I will help you. And thus this Lady Poisoner helps an empress change Roman history.

Rome is rather famous for its poisonings. Men, women, children: no one’s free from the threat of a plate of poisoned mushrooms. It becomes such a worry up in the emperor’s household that he has tasters, called praegustatores, either slaves or freedmen, taste everything before he does. Though men and women alike procure it and suffer from it, poison seems particularly tied to the ladies. We have SO many weaknesses to make up for, the ancient writers say, and how do we do that? By learning to be devious. It doesn’t help that women are often healers, particularly in villages outside the city where doctors aren’t as prevalent. Any country woman worth her salt will know at least some things about the herbs she lives with: which ones bring down fevers, which ones help with sprains. They’re likely to know which ones will hurt you, too. Aconite, which is sometimes called “women’s bane,” can apparently kill mice with its scent alone at a distance, but used properly in mulled wine it can neutralize a scorpion’s sting. Henbane causes insanity; hemlock is said to refrigerate the blood. And all of these things can be found in fields and along roadsides.

so many bad men to poison, so little time.

John William Waterhouse, “Sketch of Circe” 1911-1914. Wikicommons.

And so it is, when things in Rome seem suspicious, women often fall into the frame. Some kind of plague breaks out in 331 BCE, which has the populace very worried. Until a slave girl gets her pointer finger out and says it’s a group of Roman matrons who are poisoning us all. Some 20 women are investigated, several of them high-born ladies. Two of them plead that their concoctions are just herbs – medicines from their gardens. So the court makes them drink their own remedies and they promptly keel over from, as Livy tells us, “their own wicked practices.” Though even Livy is skeptical that any of this really happened. With their servants arrested, they inform on more lady poisoners. 170 of whom are found guilty.

Years later, another pestilence arrives. Consuls and other important men start dropping dead all over Italy. The Senate started up an investigation, which led them to Hostilia: the wife of a consul suspected of masterminding this scheme to get her son into a prime political position. On nothing but circumstantial evidence, she and 3,000 others are put to death. Witch hunts, you say? I concur.

The word veneficium means both poisoning and practicing sorcery; veneficus or venefica is what we call a poisoner or maker of drugs. Poison and magic go hand in hand, as far as the Romans are concerned, and you know which of the sexes is most likely to be accused of practicing sorcery, don’t you? Poison also seems to attach itself to women who veer out of their lane, sleeping with people who aren’t their husbands and rebelling against their strict place in society. Quintilian tells us that one Marcus Cato apparently said that “every adulteress is as good as a poisoner.”

Though many women are accused of poisoning when they shouldn’t be, some women are so good at it they turn it into a profession. We know of several who gained fame in Rome for their lethal concoctions, including Canidia, Martina, and Locusta.

After she helped murder Agrippina’s husband, Locusta finds herself back in jail. But in a sudden twist of fate, she is summoned by Agrippina’s son, now a truly terrible young emperor named Nero. He wants her help to kill his stepbrother, Britannicus, thus neutralizing the threat of his power. But when the poison acts too slowly, he beats Locusta almost senseless and forces her to mix a lethal poison in front of him. It works, sadly. And later, she’s rewarded with a full pardon, some country estates, and the title of “Imperial Poisoner.” She gets a whole school full of poison students. But then, much later, after Nero’s fall from power, she’s led through the streets in chains and put to death.

Who, me? A poisoner? Don’t be silly.

“Locusta the Poisoner” by…?! I’m having trouble finding out.

MURDEROUS BEAUTY

But I want to start in the Renaissance. The de Medici family was famous for their poisons: arsenic, antimony, mercury, lead. But plenty of other people got into it, including women. In the 1600s, a woman named Giulia Toffana got away with selling her poisons for 50 years before getting caught, almost always to women looking to become widows. Her Aqua Toffana was made with arsenic, lead, and belladonna, colorless, tasteless, and easily mixed in with wine. She often tricked authorities by bottling it up as holy water or cosmetic containers. She killed some estimated 600 people. Soulless murderess or a woman who helped other women get rid of abusive husbands? I’d like to say the latter, but we just don’t know.

But women were just as likely worrying about being poisoned as administering it themselves. Let’s start in the highest circles, where a fear of being poisoned runs rampant: in the palaces of emperors, czars and monarchs. It makes sense that they worry, because outside of disease and clueless doctors it is the stealthiest of killers: you might be poisoned at a banquet and never know what piece of food or sip of wine did you in. The kings and queens of old will spend a lot of time obsessing about it. Take Henry VIII. He employs many people to test his food for him. They drink his wine and water, taste his food, test his salt, fondle his napkin, and even kiss his tablecloth and chair to make sure there’s nothing nefarious on them. Not even church is a safe space. In 1604 King Henri IV of France goes to church to take communion, where his dog went nuts and tried to yank him back. Suspicious, he has his priest taste his wafer. “When the priest had taken it,” someone wrote of the incident, “he swelled up and his body burst in twain.” Gross. And so royals keep all sorts of bizarre cure-alls around: unicorn horn, which is actually the horn of a narwhal, is believed to detect poison. Gemstones crushed and mixed up to a fine powder are drunk as a sure-fire remedy, as are bezoars, or gall stones. Yum. If you’re really in a pinch, you can drink an antidote made out of many boiled scorpions. Whatever you say, medieval doctor!

When it comes to poison paranoia, Henry’s daughter Elizabeth I has it too. She reveres her seven-foot-long spiral unicorn horn, which is worth more than 10,000 pounds (roughly equivalent to an impressive castle), and drinks from a unicorn horn cup that is supposed to explode if poison ever touches it – hopefully before the Queen picks it up. She also has a ring made out of a bezoar, which she waves over wine and waits to see if it boils: a sure sign of something bad.

In 1560, her secretary of state William Cecil gets so concerned about a Catholic plot that he not only has her food tested, but also her clothes. No one is allowed to give her any gifts. The royal underwear and “all manner of things that shall touch any part of her majesty’s body bare” has to be both guarded and tested. She has reason to be nervous. In 1587, a French ambassador plots to have one of her gowns poisoned. In 1597, another guy smears a poisonous substance on her horse’s saddle, but she’s wearing so many layers that it doesn’t do the trick.

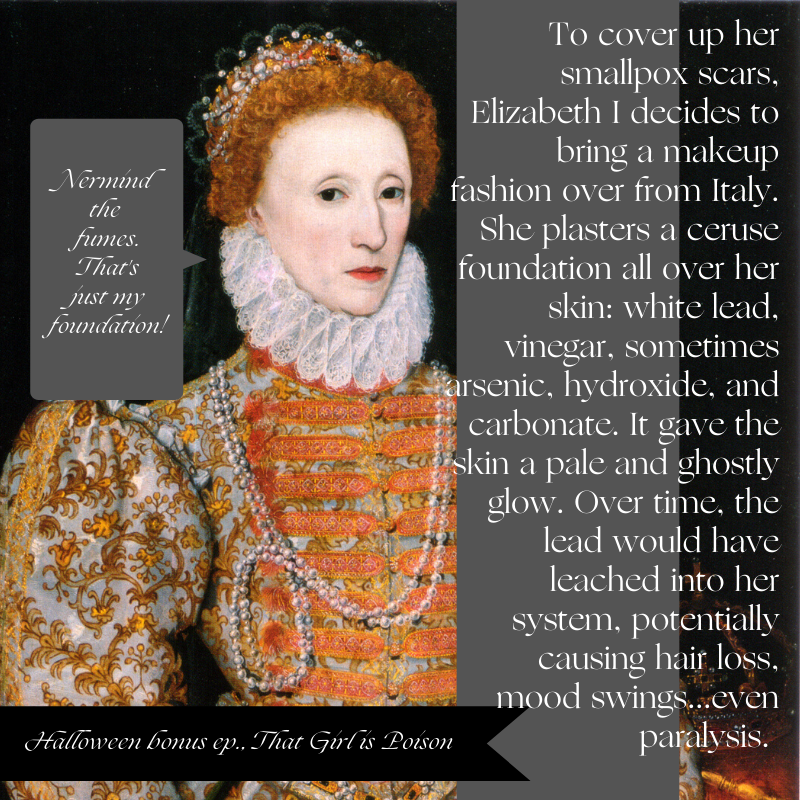

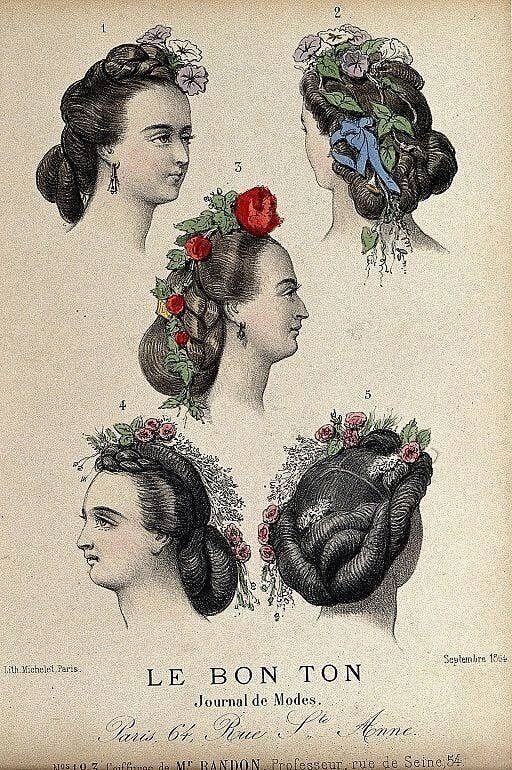

But no matter how many unicorn horns she fondles, she is slowly being poisoned every day. Not by other people’s potions, but by her own cosmetics. She worries a lot about making sure her skin looks flawless. This isn’t just about vanity: clear skin is a sign of purity, while blemishes are a sign of sin. So after she is left with smallpox scars on her face, she decides to bring a makeup fashion over from Italy: white face. She plasters a ceruse foundation all over her skin: white lead, vinegar, sometimes arsenic, hydroxide, and carbonate. It gave the skin a pale and ghostly glow, turning it almost silvery by way of refracted light. Wearing such a mixture every day means that, inevitably, the lead leaches into her system, which can cause hair loss, mood swings, even paralysis. It also corrupts the skin, making it look even more pitted, which means Queen E will feel compelled to slather more and more of it on over time. Later, in the 18th century, such mercury-based face paint kills 28-year-old socialite Maria, Countess of Coventry. Apparently her husband hates her thick white foundation so much that he chases her around the table at one dinner party, shaking his napkin and trying to wipe the stuff off. This famed beauty suffers horrible headaches, red cheeks, swollen eyes, loose teeth, tremors: all in the name of beauty.

Queen E and her ladies take it further: they comb their lashes and brows with a lead comb soaked in vinegar, which would have ensured the lead was allowed to leach out. They put belladonna drops in their eyes to make them sparkle. They whiten their teeth with crushed grains of pumice stone, honey, pearls and more cooked in silver or gold. There were chemical peels, too, full of mercury. The Queen also uses vermillion to add a bit of color. It contains powdered cinnabar, used way back in Roman times, which held mercury. Where she led, her ladies followed. Since her red hair was all the rage in England, women powdered their wigs red with a mix of sulfur and safflower petals. They gave them nausea, headaches and nosebleeds, but hey, they’re looking pretty fly!

In her final years she was said to be moody, taken to bouts of rage and depression. It could have been older age and the stresses of running an empire with everyone forever trying to marry you off. Or it could have been the effects of decades of poisoning.

She wouldn’t be the first royal woman to meet such a fate. In the first half of the 1500s, a woman named Diane de Poitiers was French King Henri II’s most beloved mistress. Though much older than he was, he doted on her, much to the annoyance of his wife Catherine De Medici. To stay in the king’s favor, this renowned beauty went to great lengths to keep herself looking young and fine.

That included concoctions filled with gold. A contemporary of hers, Maister Alexis, advised women to “dissolve and reduct gold into a potable liquor.” You take 24-karat gold foil and distill it with lemon juice, wine, and more, then put it in a clay pot and cook it. “This doing so,” says the Maister, “ye shall have a right natural and perfect potable golde, taken everie month once or twice…verie excellent to preserve youth and health.”

But we think she must have been drinking such a concoction much more regularly: enough that it eventually killed her. In 2008, a team of researchers set out to exhume her body. When they finally found her, they also found a lock of her hair, kept for posterity in a nearby chateau. That hair contained 250 times more gold than you’d expect to find in a person, and some seriously high mercury levels. It would have damaged her kidneys, made her bones brittle, inflame her intestines. In short, her beauty regimen killed her.

She wasn’t be the first to be killed by her desire to look beautiful. She certainly isn’t going to be the last.

DEADLY FASHIONS

And so we emerge back where we started, in Season 1: the Victorian era. A place where medical practice is typically a lot more likely to kill you than cure you, and where herbal medicine and prayer are often your best bet. Remember when we learned about mercury enemas and vapor baths as a treatment for syphilis? Arsenic, in particular, makes its way into Victorian life, as medicine and other things. It can be found in rat poison, but also food coloring, clothes, homes decor, even baby carriages. Why? In large part because of the color green.

In 1778, a Swedish chemist named Carl Sheele makes a fashion-changing discovery. He figured out how to use copper arsenite – copper mixed with highly toxic arsenic, also called “white arsenic” – to create a fetching bright green color. Just a year before the color went into production, he wrote a letter to his friend musing that perhaps consumers ought to be told about its potentially poisonous nature. And yet he didn’t, or else this voice wasn’t heard.

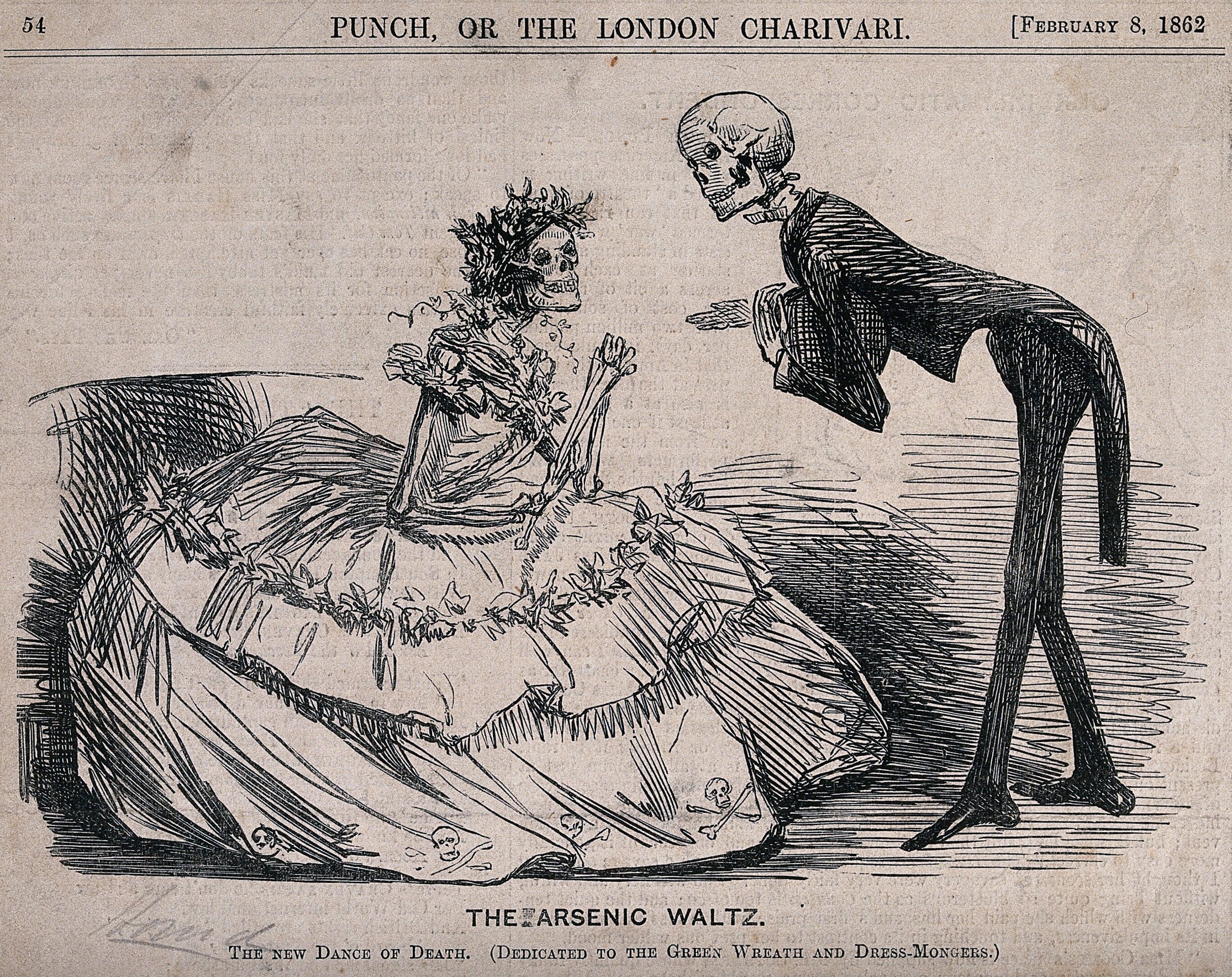

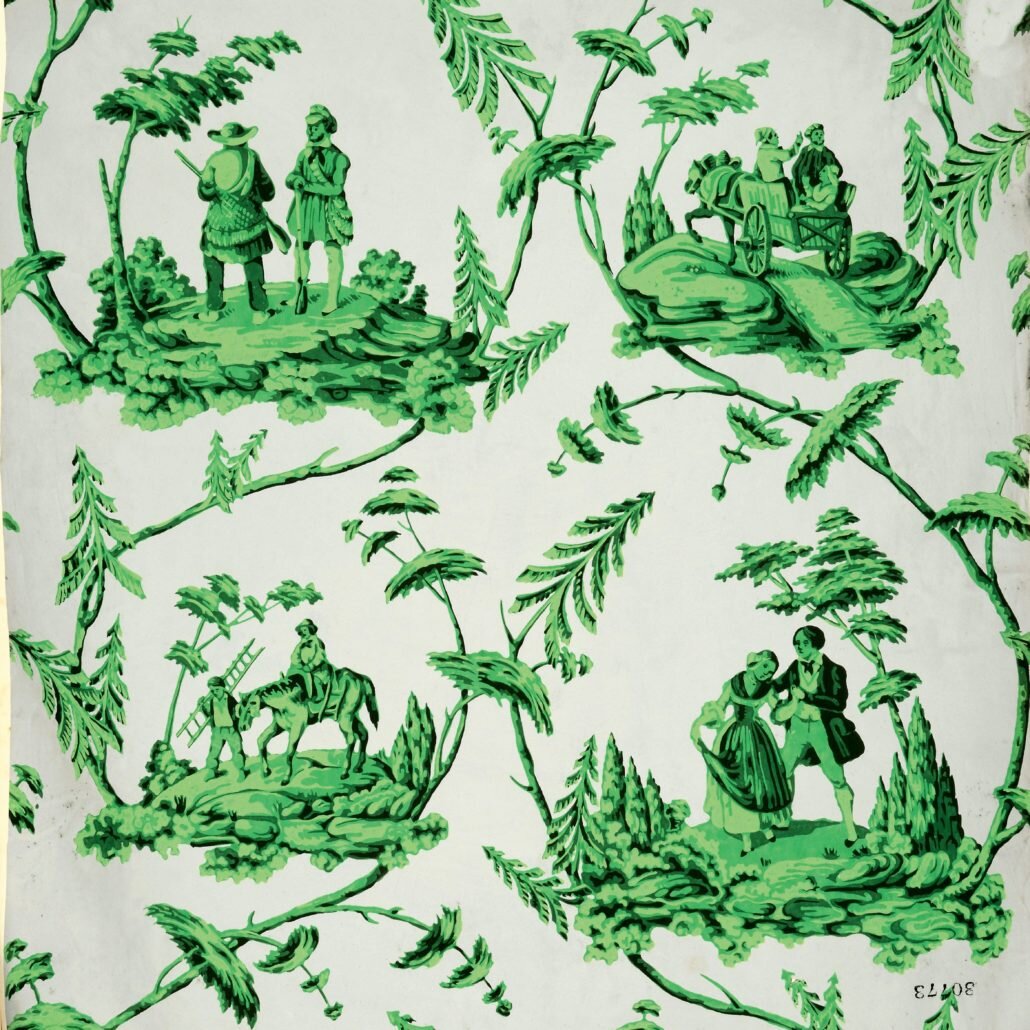

By the 1800s, this relatively inexpensive and luminous color is proceeding to become all the rage. “Scheel’s Green” was only one version – there was Emerald Green, Paris Green and Schweinfurt Green. No matter which you favored, it found its way into art, ball gowns, wallpaper, curtains: even confectionery. It’s just so bright: so vibrant it almost glows under gas lamps, which made it the perfect thing to stand out in a gas-lit room. Victorian Britain is said to be “bathed in green.” Little did they know that made it so very vibrant was going to wreak all sorts of horrifying havoc.

Though it was known to contain arsenic, most people thought it harmless: such a low concentration, and when used in such a way, it wouldn’t hurt consumers. But as early as 1839, a well-known German chemist named Leopold Gmelin wrote that damp rooms with green wallpaper often had a “mouse-like odour:” the product, he warned, of the production of dimethyl arsinic acid within it. He tells a newspaper all about his concerns. In 1857, every time an English doctor named William Hinds retires to his study in the evening, he feels the overwhelming urge to throw up and suffers from terrible cramps. He’s growing desperate when he finally realizes that these symptoms only ever come on when he’s in the one room, so he scrapes samples of his fetching green wallpaper. Once he determines they have arsenic in them and he gets it removed, his symptoms vanish. He wrote later that “a great deal of slow poisoning is going on in Great Britain.”

In 1862, four children in London’s working-class Limehouse district suffered from a strange illness – sore throats, breathing issues – falling one after the other like dominoes. Though it was written off as diphtheria, doctor Thomas Orton was perplexed as to why, in a tightly-packed neighborhood, only these children in this house and not others had suffered, and why they hadn’t responded to the diphtheria treatments administered. In desperation, he catalogued the family’s living conditions: the condition of their house and what was in it. The green wallpaper made him pause, because he’d heard rumors that it might be poisonous: he started connecting the toxic dots. So he got renowned chemist Henry Letheby to test the children’s skin, only to discover arsenic poisoning. He found that the paper contained three grains per square foot of arsenic; in an adult, all it takes is four or five to prove lethal. You didn’t even have to be in the same ROOM, he said: “I have known two children die from arsenical poison imbibed while playing for a few hours daily in their father’s library.”

And yet many refused to take the threat seriously. As we learned in an earlier bonus from this time last year, “Murderous Mysteries,” a woman named Lydia Sherman became quite famous in 1870s America for poisoning several husbands and children with arsenic. In 1867 in an Illinois hotel, 20 people ate biscuits mistakenly made with arsenic powder instead of flour and got violently ill with stomach cramps, sore throats and convulsions. Everybody knew it was poisonous. But not everyone thought that arsenic-infused fashion could be deadly.

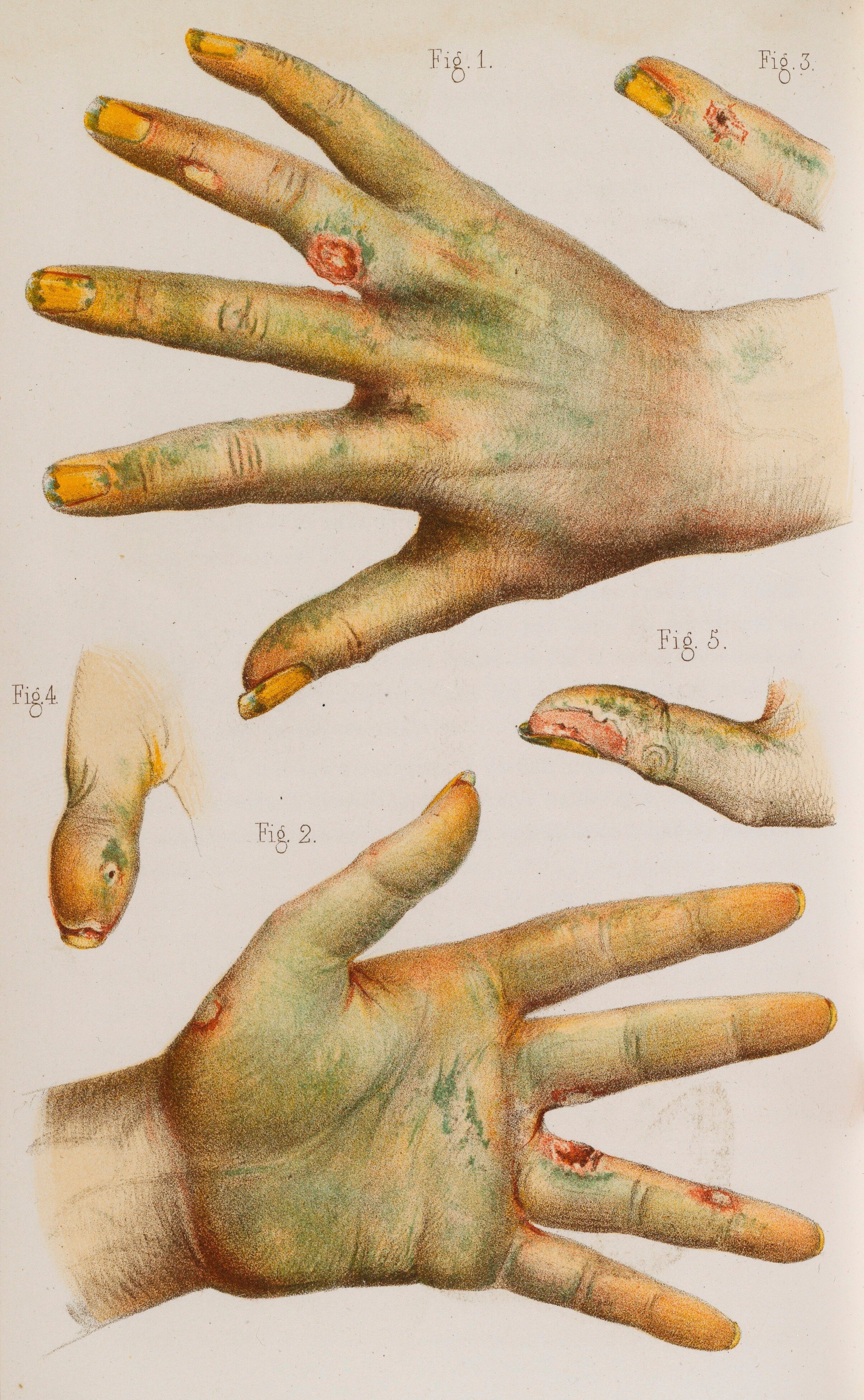

Victorians ate vegetables sprayed with arsenic insecticides; lickable stamps were colored with arsenical dyes; and the siren song of that beautiful green meant that people were wrapping themselves in clothes made out of it. Cravats, fake flower wreaths, whole dresses. In 1871, a woman was fairly upset to take off her fetching green gloves and find her hands covered in blisters, the poison mixing with her sweaty palms.

Some simply thought the doctors were wrong, the reports of killer fashion sensationalized. Even doctors doubted such findings, as plenty of people had green wallpapers in their homes and no one in their family ever got sick from it. This is probably because while children were particularly susceptible to lower levels of arsenic, adults could typically handle such exposure with little problem. Later studies also showed that those who ate a lot of protein were better able to cope.

William Morris was the most famous wallpaper artist of the nineteenth century – a British textile designer, novelist, translator, and leading light in the British Arts and Crafts Movement. He also owned shares in his dad’s mining company, Devon Great Consols (DGC), the largest arsenic-producing business in the country. He didn’t believe the stories about arsenic in home décor being deadly: after all, he had it on his walls, and he didn’t see any of his dinner guests getting sick. It’s not as if anyone’s going to be licking them! Even in 1885, long after public pressure forced him to stop using it, he wrote to a friend: “As to the arsenic scare a greater folly it is hardly possible to image. The doctors were bitten as people were bitten by the witch fever. My belief about it all is that doctors find their patients ailing, don’t know what’s the matter with them, and in despair put it down to the wall papers when they probably ought to put it down to the water closet, which I believe to be the source of all illness.”

But Queen Victoria knew, or at least suspected. In 1879, she got very angry at a visiting dignitary who’d failed to show up to see her on time. When he finally got there, he apologized profusely, saying that he couldn’t help it: Buckingham Palace’s green wallpaper had made him quite sick. She immediately had it stripped, which caused others in England to do it too.

The thing that William Morris and others failed to understand was that it wasn’t just on the walls: it was in the air. Years before, in the 1850s, British political activist Harriet Martineau wrote about green dust falling from such walls, calling them “prettily hung, not long ago, with a paper where a bright green trail of foliage was the most conspicuous part of the pattern. Day after day everything in the room was found covered with a green dust….” And guess what? It’s this very green that some have suggested may have killed Napoleon Bonaparte. After his final defeat, Napoleon was sent to exile on the island of St. Helena in 1815. Lucky for him he lived in relative luxury, hanging out in a room painted in his favorite color – green. He later died of what we think was stomach cancer, or maybe ulcers. Analysis of his hair samples, however, showed a whole lot of arsenic.

Was it the tiny flakes from such prettily hung wallpapers that got him? Plenty of contemporaries reported on such dust, but said that it wasn’t always harmful. It wasn’t until 1891 that doctors realized that the pigment could be volatilized by fungi, releasing an arsenic gas. Perhaps those who didn’t get sick were lucky with the temperature and dampness levels in their homes, but not Napoleon. Death by design…what a way to go.

But it was the girls who worked with the substance who had it worst. In workshops where artificial flowers are made, fake leaves are often dusted with a green arsenic powder, never knowing that its contact with their skin and lungs was poisoning them at work every day. In 1861, a 19-year-old artificial flower maker named Matilda Scheurer died of “accidental” poisoning in London. Before long she is throwing up green water; even her fingernails and the whites of her eyes had turned an emerald green. She died in pain and foaming at the mouth. After that, organizations like the Ladies’ Sanitary Association got involved, noting that more and more girls were refusing to work with the stuff, and others who felt compelled to continue ended up with horrible sores on their faces and with sore, bandaged hands. This organization got an expert to come in and run a test on an average flower-wreath headdress.

In a London times article called “The Dance of Death,” he concluded that it contained enough arsenic to poison some 20 people. A ball gown made from 20 yards of such green-dyed fabric contained 900 grains of arsenic, flaking off on the woman wearing it and anyone who touched it. A grain is equivalent to 64.8 milligrams or 1/7000th of a pound, and only four or five were needed to prove lethal. Instead of getting upset at manufacturers, though, a writer at the British Medical Journal said this of women who wore it: “Well may the fascinating wearer of it be called a killing creature. She actually carries in her skirts poison enough to slay the whole of the admirers she may meet with in half a dozen ball-rooms.” But those same women are the ones who blew the whole thing wide open by bringing in chemists to save the girls who work with it. Both victims and their own saviors, too.

Although we’re focused on poison here, I feel we have to admit that it isn’t just green dresses that Victorian women have to worry about. For all the talk about the dangers of their hoop skirts – and let’s be honest, they did come with some safety concerns – the materials of ALL their dresses are extremely flammable, and they live in a world that is lit by open flames. Dancers are particularly imperiled by flammable garments. The gauzier the costume, the more likely it is to burn quickly…many of them died by fire on stage.

GLOWING IN THE DARK

But sometimes it's our desire to get ahead that hurts us. For women who work in factories post Industrial Revolution, this is especially true. Sometimes it is the work conditions that kill them. But sometimes the product itself is a poison: a silent killer in the guise of glamor, working its way into their bodies.

It’s the 19-teens, and with World War I declared, women are lining up to go to work painting watches with luminescent paint, which makes them glow an iridescent green. These working gals become known as “ghost girls” because of the way their day job leaves them glowing. They make the most of it by wearing their good dresses to work so that later, in the dance hall, they’ll shimmer. It is considered a good and coveted job: one that pays some three times more than other factory positions and has a much cooler vibe about it. Women join up, then tell their sisters and friends to come with them.

Women paint their dials with radium with no gloves, no masks, and no idea of how their job could hurt them.

From 1922, Wikicommons.

It isn’t easy work. The watch dials are small, making them a very tiny target for painting. For best accuracy, the girls are all taught to lip-point: stick the brushes in their mouths to get them to a fine point, dip them in paint, coat the dial and do it all again. Never mind that the luminescent paint they’re using gets its signature glow from radium! It’s harmless, their superiors say – and the girls trust them. Little do they know they are poisoning themselves to death.

Like with arsenic paint, people know radium is dangerous. As early as 1900 a French physicist named Antoine Becquerel carried a small vial of it around in his waistcoat pocket for just six hours and reported that his skin bloomed with ulcers. But used in such small quantities, most experts say it’s fine. In fact, it’s good for you! You can buy radium water as a tonic: the recommended dose is 5 to 7 glasses daily. It’s in cosmetics, jockstraps and lingerie, butter, milk…even toothpaste. And so the dial painters go on merrily dipping it into their mouths hundreds of times a day.

But then they start getting sick. The first comes in 1922. A girl named Mollie Maggia has to quit because she feels so sick and nobody can figure out what was wrong with her. Her aching tooth won’t quit, so her dentist pulls it out. But then another starts to ache, and then another, filling when they’re pulled with bleeding ulcers and pus. At one point, her dentist prods her jaw and it breaks against his fingers. All he has to do is reach in and lift the whole thing out. Her limbs ache too: at a certain point she can’t even walk. In just eight months, Mollie is dead, and no one can say what happened.

The radium gives them horrible cancers and bores holes inside them. It literally eats them alive, killing dozens over several years. And for a long time the companies hush it up. Even when the girls start to complain more and more loudly, the company doctors diagnose the issue: they’re suffering from syphilis. Think about that for a minute: being a young girl in the 1920s, sick and in pain, being publicly accused of having an STD. Of course it’s YOUR fault, you brazen hussy! And people believe it. But the girls and their families know better.

Still, the companies continue on with their practices: the men in the factory wear lead aprons when they work with radium, but they don’t offer any such protection to the girls: they refuse to admit that they are poisoning their workers.

This story is a heart-wrenching saga, and I could go on about the girls it affects, but let’s skip to the small and impactful silver lining. Seeing that something needs to be done, many of the afflicted women band together to fight back and make the companies listen. They want to be recognized and have their med bills paid, but more than anything they want to save others. “It is not for myself I care,” dial painter Grace Fryer said. “I am thinking more of the hundreds of girls to whom this may serve as an example.”

They fight to find a lawyer, though so many turn them down, either disbelieving their claims or just afraid to take on the big bad corporate. Some women are so determined that they give testimonies even from their deathbeds. And eventually, they do triumph: they make the companies admit their part and prove that it’s the radium that killed them. Some of the girls were compensated, while others aren’t. And of course, so many of them die along the way. Those that live often do so in pain, both emotional and physical. But the Radium Girls are some of the first workers to make a company responsible for the health of their employees. Their fight leads to life-saving regulations in the workplace and the establishment of the Occupational Safety and Health Administration. They fight in ways the artificial flower makers who came before them couldn’t, and though some lost their lives, they left us with a powerful legacy.

The Radium Girls fought through their own pain to make sure other girls would never suffer as they did.

Excerpt from the Worcester Democrat, Wikicommons.

CONCLUSION

I started this episode wanting to talk about how women have wielded poison, both for good and evil. But what I kept coming back to was how women are forever poisoning themselves or being poisoned by the products they covet and are told they need to look and feel their best. And while these all feel like issues of the past, perhaps they’re not.

In 2009, an 81-year-old woman named Evelyn Rogoff went to make herself a cup of green tea and her chenille bathrobe touched the electric burner, resulting in her death by fire. In Quebec in 2012, a new bride wanted some “trash the dress” photos of her wading into a river, where the dress quickly became soaked in water, helping the current drag her down to her death.

But this isn’t just isolated dangers we’re talking about: our makeup and other hair and skincare products are also potentially dangerous. In the USA, the cosmetics industry is barely regulated: you can put whatever chemicals you like in them.

The EU has banned or restricted more than 1,300 chemicals. Of the 40,000 chemicals on the US market,we’ve done that for just 11 of them. Is it just me, or does this seem like some sketchy math? We might be using formaldehyde in our hair-straightening treatments and nail polish. Or parabens, linked to reproductive issues, in our skin and hair products. Coal tar dyes in our eyeshadow. I don’t know about you, but I find that pretty haunting.