Cleopatra: She Came, She Saw, She Conquered

Cleopatra, the last great queen of Egypt, doesn’t really need an introduction.

You can see her in your mind already, can’t you? Pretty and sultry with her cat-eye makeup, covered head to toe in shiny gold. Extravagant, self-serving, ruthless: this epic seductress used every magic trick in her lady arsenal to hold onto power, no matter the cost. Didn’t she? That’s the Cleopatra the ancient Romans want us to see.

The truth is that few women’s stories have been more brutally revised by sexist haters threatened by a woman’s right to rule. The Romans used her as a scapegoat to explain away two powerful Roman men’s actions – because there’s no WAY big top dogs Julius Caesar and Mark Antony would have done the crazy things they did with her unless she used her feminine wiles to lay down some sexy sorcery!

Most Roman writers take pains to make her the villain of their stories. Ancient writers got out their hater brush for Cleopatra, running one of the ancient world’s most effective smear campaigns. Where we might see an intelligent, savvy, thoughtful leader, ancient writers turn her into, as Cicero put it, an “uncommonly impertinent harlot.” Cassius Dio calls her “a woman of insatiable sexuality and insatiable avarice.” Plutarch claims she showed “unseemly opulence”; Flavius Josephus jumps on the slut-shaming wagon and calls her an “extravagant woman” who was “by nature very covetous” and “a slave to her lusts”; Roman poet Lucan, the drama queen, calls her “the shame of Egypt, the lascivious fury who was to become the bane of Rome.” Greek writers supposedly called her meriochane, which translates to something like “she who gapes wide for 10,000 men.” Um, rude.

The themes here are clear: Cleo wanted too much – in bed and in politics – and was way too greedy and emotionally volatile to be trusted with any real power. But clear away the acrid smoke of sexist Roman killjoys and another picture emerges: of a deft and capable pharaoh who ruled one of the most powerful empires the ancient world would ever see. This last pharaoh of Egypt was dealt an impossible hand, and yet she stayed on top of the game for decades when lesser women would have crumbled.

Temptress, schemer, mother, witch, party girl, strategist, warrior…over the years she’s collected an impressive list of adjectives, her image fixed in our imaginations. But is that image nothing more than a fantasy? We don’t know what she looked like; we have next to nothing in her words. Only one can possibly be credited to Cleo, though it’s pretty fitting. In 33 BCE, either she or her scribe signed a royal degree with the Greek word ginesthoi, or: “Make it so.” And though we all know her name, so much about her is a mystery. Who was Cleopatra, beyond the smoke and hate and all that glitter? Let’s travel back and see if we can find her. Grab your strappy sandals, some hot pink smoke bombs, and your shiniest diadem. Let’s go traveling.

Grab your sandals, your hot pink-colored smoke, and your nicest diadem. Let’s go traveling.

Move over, ancient world. Cleopatra is coming.

Cleopatras II and III, from Kom Ombo Temple. Wikicommons.

research SOURCES

BOOKS

Cleopatra: A Life. Stacy Schiff, Virgin, Sept. 2011. This one is fantastic: so thorough and so readable. If you want to find out more about Cleopatra, this is the place to turn.

When Women Ruled the World. Kara Cooney, National Geographic, Nov. 2018.

Cleopatra of Egypt: From History to Myth. Eds. Susan Walk and Peter Higgs. Princeton University Press, 2011.

Cleopatra: A Sourcebook. Prudence J. Jones, Oklahoma Series in Classical Culture.

Kings of the Bible. National Geographic Special Edition, 2019.

ONLINE

“Who Was Cleopatra? Mythology, Propaganda, Liz Taylor and the real Queen of the Nile.” Amy Crawford, Smithsonian Magazine, Mar. 2017.

“Raising Alexandria” by Andrew Lawler, Smithsonian Magazine, Apr. 2007.

“Isis: Worship of this Egyptian Goddess Spread from Egypt to England.” Jamie Alvar, National Geographic History, 2020.

“Make It SO! Sayeth Cleopatra.” Angela M. H. Schuster, Archaeology Magazine News brief, Volume 54 Number 1, January/February 2001.

“THEDA BARA AS CLEOPATRA.; With Much Rolling of Eyes She Portrays "the Siren of All Ages.” The New York Times, Oct. 1917.

“Cleopatra’s Legacy in Art.” by Hermenia Powers, Art UK, Mar 2020.

“How Millennia of Cleopatra Portrayals Reveal Evolving Perceptions of Sex, Women, and Race.” Alina Cohen, May 2018.

“Sculptor Edmonia Lewis Shattered Gender and Race Expectations in 19th-Century America.” Alice George, Smithsonian Magazine, Aug. 2019.

“Almost all of the actresses who’ve played Cleopatra have been white. But was she?” Nadra Little, Vox.com, Jan. 2019.

Flavius Josephus, The Antiquities of the Jews, 15.88–15.107. Lexundria.

Plutarch, Antony. Perseus online database.

Plutarch, Caesar. Perseus online database.

If you like this map, you can grab a printed poster of it in my Etsy shop. Just go to the tab labeled “Merch” above!

transcript

please keep in mind that I edit a bit as I record, so this won’t match the audio exactly. Also, it’s likely you’ll find typos or funny formatting issues here and there: do forgive me. also, the quotes in bold are ones I’ve made up for the drama, so please don’t quote them as fact in your high school history paper!

PART 1

Before we start, I’d like to point out there’s a reason I’ve saved Cleopatra for so late in Season 2. To truly understand her story, you’ll need to have listened to my series on women in ancient Egypt, Greece, AND Rome thus far, particularly the episodes on lady pharaohs and Olympias, Alexander the Great’s mom. Those will give you the background you need to appreciate the world we’re about to time travel back to.

Let’s start around 69 BCE, around when our Cleopatra is born. But first, let’s hover over the Nile River Delta, right over the port city of Alexandria, and soak in the big picture. You might be picturing, say, Nefertiti or Hatshepsut’s Egypt, but Cleo’s world looks very different than it did when our other female pharaohs ruled. This soon-to-be pharaoh queen comes into the world at the tail end of Egypt’s majesty. We’re more than 2,000 years past the construction of the great pyramids of Giza. It’s been more than 1,000 years since the last lady pharaoh we covered, Tawosret, was rocking that crook and flail. And though Cleo is considered Egypt’s last pharaoh, it turns out that in some ways she isn’t Egyptian at all.

Between the New Kingdom period, which started in the 16th century BCE and saw such lady greats as Nefertiti and Hatshepsut, and 69 BCE, Lady Egypt was invaded and overrun by foreign powers, such as the Assyrians and Babylonians. It’s been a rotating door of extremely bad dates. Then, finally, in swept Alexander the Great, that studly Macedonian god-king who absolutely slayed when it came to dominating other empires. Alex is pretty famous, as you already know, for building the largest empire the ancient world would ever see and giving every Greek and Roman after him a very tiny man complex. And by the time Olympias’s son arrived in Egypt on his steed in 332 BCE, the Egyptians were maybe almost excited to see him. I mean, at least he’s acting like a proper pharaoh, they said. And I mean, he isn’t Persian…so, that’s good. Let’s declare him an Egyptian god and make him our pharaoh!

Hey, Egypt! Let’s do this.

Alexander the Great, Roman floor mosaic, originally from the House of the Faun in Pompeii . Wikicommons.

God status achieved, Alexander set about putting his personal stamp on this part of the Mediterranean. It was while trotting through Egypt to see an oracle in 331 BCE that he had a vision of a great city that would link Greece and Egypt. It would be some 20 miles west of the Nile’s opening, on a narrow spit of land jutting out between the sea and a lake. A canal dug to the Nile would provide fresh water and transport to the interior. He called it Alexandria, because he sure did love naming cities after himself! But then he died rather suddenly at the tender age of 32, but he didn’t leave clear directions about who should take over after him. So after some very tense skirmishing, his land was divvied up among his closest bros. Cassander got Macedonia and Greece, Lysimachus got Anatolia, and this guy named Ptolemy got Palestine, Cilicia, Petra, Cyprus, and – you guessed it – Egypt. This ancestor of our girl Cleopatra was actually a childhood friend of Alexander’s, the son of a country squire and a princess. For a time he was also Alex’s official taster, which may be why the Ptolemies seem to have a thing for poison. But Ptolemy had a problem: how do I get the people of Egypt to see me as their leader? Luck would have it that as he was mulling the problem over, he was helping escort Alexander’s body back to Macedonia for burial. Then Ptolemy had a lightbulb moment. “You know what? Imma steal that body.” And so he whisked Alex’s corpse away to Alexandria, put him in a gold sarcophagus in a public place, and was like, “see Alex, everybody? All draped in gold in stuff? What a total god he was – and you know I’m basically kind of MAYBE related to him, so that means I’M a god too, and it totally makes sense that I be your new pharaoh! So don’t try and overthrow me, k? Thanks byeeeeee.”

And that is how a Macedonian Greek family came to rule Egypt for the next 300 years. I’m sure some Egyptians were unsure about this new regime, and about moving the capital city from Thebes to this new city, but Egyptians really wanted to Make Egypt Great Again, and for that they needed a ruling family. And unlike the people who’d ruled previously, at least the Ptolemies actually based themselves in Egypt, and they were eager to lean into Egyptian culture, at least in some ways. They cast off their Greek getups and adopted that Egyptian god-king lifestyle, seducing the people into thinking that maybe Ptolemy was meant to rule after all.

Going Egyptian also meant reintroducing the whole brother-sister-daddy-wife incestuous marriage cycle. When he first settles in Egypt, Ptolemy is all ready to follow Macedonian custom: just like Olympias’s husband Philip II and Alexander before him, he took several wives. But then his daughter, Arsinoe, saw an opportunity: she convinced her brother, also named Ptolemy, to marry her against Greek custom, thus establishing herself as his co-ruler: his equal. I have a lot to say about Arsinoe’s rollercoaster life, and how she set the tone for all the women to come after her. You’ll find a bonus episode about her on my Patreon very soon. For now, let’s just say that is how Egyptian women once again found themselves with a clear path to the power seat if they were game enough to grab it.

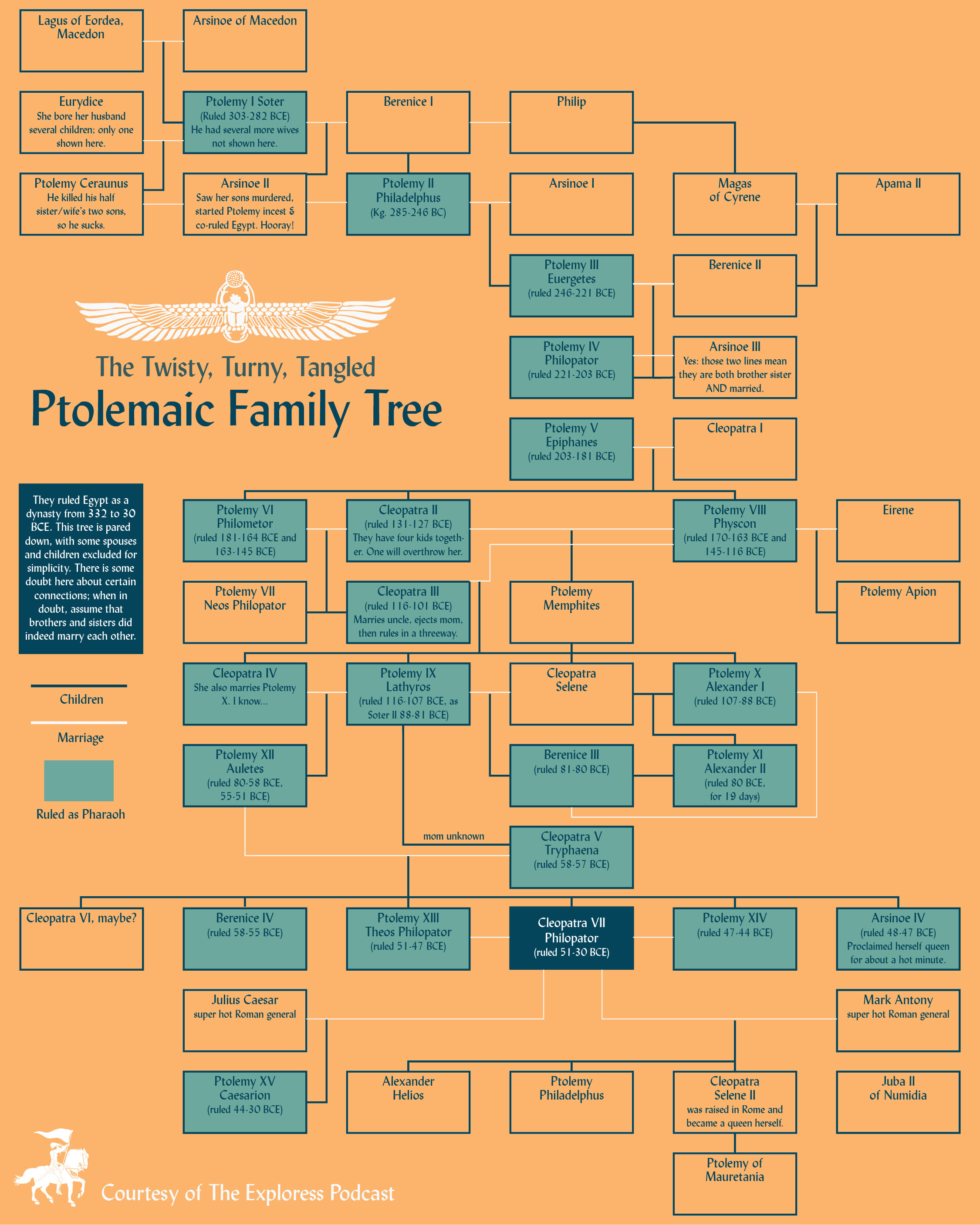

Dynastic origins established, we fast forward through several decades of intense family rivalry to get back to 69 BCE. As we do, be aware that this family has a very short list of baby names. There’s really only one name for boys - Ptolemy - and for girls there’s three: Berenice, Arsinoe, and Cleopatra (which is actually a Greek name, did you know, meaning “Glory of her Fatherland”). To keep things straight, they often picked up nicknames: that first Ptolemy, for example, was Ptolemy Soter, which meant “Savior.” Historians have also given each of them numbers so we can tell who’s who. How about a visual to help make sense of this twisty-turny family tree?...

It must be said that the Ptolemy Family makes the Lannisters from Game of Thrones look like a bunch of My Little Ponies. They’re incestuous and cutthroat, like the Lannisters, but they take both of those things to a whole other level. Don’t like your brother husband? Poison him, naturally. Want dad out of the way? Knife to the ribs, no big deal. When it comes to role models, Cleopatra has some intense female family members to learn from. We’ll talk about Arinoe II, that first Ptolemy’s daughter, in that bonus, but some high and lowlights of her life include: marrying a king, having her two sons murdered in front of her, fleeing from the half-brother who killed her kids and stole their throne, and then marrying her full-blood brother to become one of the most influential women in the ancient world. Allllrighty then! A bit further down the family tree we have mother-daughter duo Cleopatras II and III. Cleo III isn’t a big fan of her mom, it seems, so she deposes her and promptly marries her mother’s husband and her own uncle, Ptolemy VIII. Nevermind that his nickname is Physkon, or “Pot-belly.” Just lie back and think of Egypt! But Cleo II isn’t about to retire and move to the Gold Coast. She raises an army and uses it to drive Cleo III and brother-husband right out of Egypt. Ptolemy VIII gets her back by murdering their son together, chopping him into several pieces, and sending him wrapped up like a present to Alexandria for Cleo II’s birthday. Wait...what? Eventually, they all settle into a very bizarre ruling threesome. I’ll bet they all sleep super soundly at night.

An Egyptian wall relief showing Cleopatra III, Cleopatra II, and Ptolemy VIII before Horus. Just your average incestuous threesome. Wikicommons.

This is all to highlight a simple, strange truth about Cleopatra’s story: she is born and raised in what’s essentially the family edition of the Hunger Games. She grows up surrounded by subterfuge, political backbiting, and the kind of life where you never drink out of a cup before a slave tastes its contents for you. She knows that if she doesn’t end up in power herself, whoever is will see her as a threat and seek to destroy her. It’s a life where loyalty means both everything and nothing; where love can be a powerful bond and a weakness, and trust is a luxury you can’t often afford. Kara Cooney, author of the excellent book When Women Ruled the World, puts it best when she says: “Ptolemaic life was one of persistent PTSD.”

What would this childhood feel like? Would Cleo have run through the gilded halls of the palace with her sisters, laughing and playing make-believe, before they were old enough to understand they’d probably end up killing each other? Was there love here, or only animosity? Each of them is surrounded by a team of hangers-on: tutors, advisors, generals, moneymen, all hoping to make their young charge the next king or queen of Egypt. They fight her battles until she’s old enough to fight them for herself.

It’s easy to imagine that this childhood doesn’t engender much trust or compassion. It does, however, shape her to successfully rule a country in a very troubled time. But to make it to adulthood—which is no guarantee—she’ll have to have a sharp mind, a clear grasp of politics, a decisive wit, the ability to adapt to changing circumstances, a strong sense of her worth, and a real sense of entitlement. Luckily, she’ll have all of these things in spades.

Cleo’s father is a guy named Ptolemy XII. He became unlikely pharaoh in 80 BCE, when the direct family line looked up and was like, “oh, wait: did we kill everybody? Shit, we did. Better find a second cousin!”

He was the son of a Ptolemy, Ptolemy IX Soter II, but his mom was only one of his side pieces, so his claim to the throne was tenuous at best. His grandmother, the cutthroat Cleo III, sent him away from Alexandria years before to keep him out of danger, doing we have no idea what. Maybe he was groomed for kingly greatness...or maybe he looked up in 80 BCE and was like, “Wait, what? Me? Pharaoh? Oh... I mean, sure. I guess I can make that could work.” Since the elite of Alexandria are big on their kings being too legit to quit, he makes sure to solidify his claim quickly, renaming himself the “New Dionysus” to give himself some extra swagger. But most people call him by one of two nicknames: Nothus, or “Bastard,” and Auletes, Greek for “Piper” or “flute player.” This last is because he’s fond of playing an oboe-like instrument that is apparently a favorite among prostitutes. Mmk.

But it works for Cleo’s dad. He’s fond of wine, parties, women, and whaling on his flute. As Strabo said, “...apart from his general licentiousness, [he] practiced the accompaniment of choruses with the flute, and upon this he prided himself so much that he would not hesitate to celebrate contests in the royal palace, and at these contests would come forward to vie with the opposing contestants.”

Though in the midst of all these epic jam sessions, he does a pretty good job of producing future Ptolemies. It’s interesting to note that though the family is into incestuous closed-loop marriages, it doesn't seem like they have the same incest-related issues as the earlier pharaohs. That might be because, though Ptolemy XII marries his sister (or maybe cousin) Cleopatra V Tryphaena, he definitely takes unrelated mistresses on the side. The Ptolemies don’t have official harems like the old dynasties used to, just dalliances out of wedlock, which can make lines of succession fairly confusing. Some people think Cleo herself might have been the product of such a union. Either way, we know next to nothing about her mom of record, Cleopatra V Tryphaena, who falls off the face of ancient records the same year Cleo’s born.

Ptolemy the sexy flautist also has two sons, BOTH named Ptolemy, and two other daughters: Berenice and Arsinoe. Cleo, we think, is the middle child.

There’s a lot we don’t know for certain about Cleo’s childhood, but plenty we can infer. For one, she’s raised by a horde of royal helpers: wet nurses, nannies, servants, bodyguards, hangers on, tutors. There will be at least one official taster who chews her stewed carrots to make sure there isn’t any poison in them. She’ll have a girl gang of noble children to run around with. Each child will have a whole team of people around them, very interested in keeping them alive to claim power.

When no one’s trying to kill her, it’s a lush and indulgent existence in one of the ancient world’s richest and most beautiful cities. Imagine her running down hallways filled with tiles of ebony and ivory, over lush Persian carpets and leopard skin rugs, through doors decorated with mother of pearl, garnet, and topaz. She’s playing in palace gardens where keen zoologist Ptolemy II is said to have once kept giraffes, bears, and pythons. She’s taking trips during the festival season down the Nile between Alexandria and Memphis, dressing up and participating in cult rituals to remind the people of the family’s divine right to rule. Through it all, she’s receiving the best education a Hellenic girl can buy. And she’s an excellent student, keen to soak up everything she can.

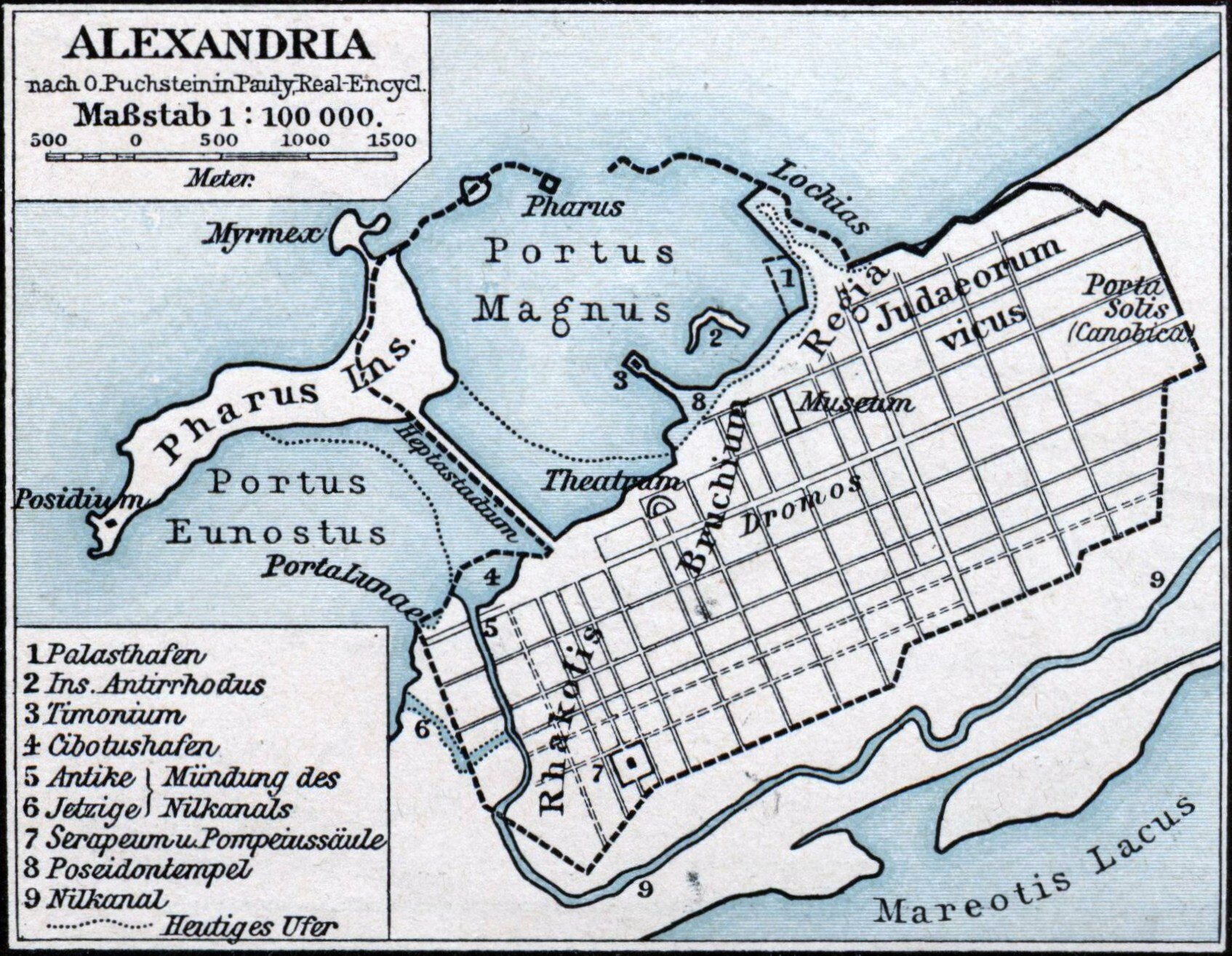

HOMETOWN ALEXANDRIA

Alexandria, Baedeker, Karl Egypt, handbook for travellers, London 1885. Rice University

Let’s talk about her hometown, as it’s a place whose streets we’ll want to get lost in. Despite the many years of stabby family relations between that first Ptolemy and this latest one, the family has managed not only to hold onto and expand Egypt’s border, but to bring Alexander’s dream city to life. It’s in essence a Greek city, full of Greek language, art, and culture, but with distinctly Egyptian accents. If the ancient world had a Most Livable Cities List, Alexandria would top it every time.

Sailing into this walled city on a narrow strip of peninsula, you’re greeted by the city’s great pharos, or lighthouse. It’s the world’s first such structure, and it’s the reason we call tall structures with flaming lights atop them “lighthouses.” It has some five levels and stands some 455 feet (140 meters) tall, guiding sailors into port with fire by night and smoke by day, we think, and using metal mirrors to send the light over the water. It will survive for a staggering 17 centuries. They sure don’t build ‘em like they used to.

Once you’ve landed, you’ll find yourself strolling along a long, wide boulevard called the Canopic Way, which is kind of like Paris’s long promenades. It’s the grandest street in the ancient world: 80 chariots can ride down it side by side. All the better for holding grand parades, which the Ptolemies are very fond of. It runs from east to west, lined with elegant columns and silk tapestries, capped by the ‘Gate of the Moon’ on the east and the ‘Gate of the Sun’ on the west. The royal complex is quite prominent, located near the harbor. Beyond it, you’ll find bustling market stalls, vibrant shops, street performers, and lots of ibis. These black-and-white birds are sacred to Egyptians, tied to Thoth, the god of wisdom and writing. But watch out: they’ll steal your lunch if you let them. I once had one snatch a sandwich right out of my hand with its long, bendy beak.

Ships pour into this port from all over, bringing silk and spices, ebony, ivory, aromatic plants, precious metals, scrolls, perfumes. Egyptian grain flies out of its port, marching out to feed a huge proportion of the population in places like Rome. The city is heavily influenced by Greece in terms of style, language, and its love of the arts, and thus feels very different than the rest of Egypt. You’ll find public baths, giant statues, a massive gymnasium, and temples dedicated to both Greek and Egyptian gods. It’s as New York City is to New York State: a part of the greater whole, to be sure, but also its own world.

Alexandria is a diverse city. It links India, Arabia, Africa, and the Western world, and being a port city, it’s full of riches and wonders and people from everywhere. Its citizens love to have fun, to live out loud and in color. “It is not easy for a stranger to endure the clamor of so great a multitude,” said one tourist, “or to face these tens of thousands unless he comes provided with a lute and a song.”

It’s separated into ethnic quarters, all called by letters of the alphabet, making Alexandria perhaps one of the earliest cities to have street addresses as we recognize them today. Jews, Greeks, Egyptians, and others are running their own parts of town, but also mixing and melding around the many theaters, bordellos, and warehouses. Riots and protests aren’t uncommon.

“Looking at the city, I doubted whether any race of men could ever fill it. Looking at the inhabitants, I wondered whether any city could ever be large enough to hold them all.”

The Ptolemies have taken great pride in making Alexandria a place of art and learning. “The city has exceedingly beautiful public parks and palaces covering a quarter or a third of its area,” Strabo tells us, “since each of the kings, just as he contributed some enhancement to the public monuments, so too he added to the existing buildings a private residence, so that now, as the poet says, they are one on top of the other.”

The city’s famous library contains the greatest collection of knowledge in the ancient world. It’s called the Mouseion, which is Greek for “a seat or shrine of the Muses,” and is where we get the word “museum” from. Ptolemy Soter was known to hoard everything ever written, on a quest to create the world’s largest book collection. A man after my own heart, to be sure! He sent emissaries all over the world to acquire them, raiding book fairs in Rhodes and Athens; he even plundered ships coming into harbor. “Don’t worry,” he’d say. “I’ll have my scribes make a copy and give the original back to you…you know, probably.” Some say the Mouseion houses 500,000 scrolls, though it’s probably more like 100,000, including some of Sappho’s poetry. A massive number when you consider this is a time when everything is written out by hand. There’s a museum attached, where a community of scholars are given tax-free room and board so they can focus on Thinking Big Thoughts together. The circumference of the world is first measured here, coming within a few hundred miles of accurate. The sun is pinned at the center of our solar system. Legend has it that Archimedes – the guy, not the owl from Disney’s Sword in the Stone – invented his “Archimedes’ screw” here, which is a pump for transporting water from below ground to above. Kind of a big deal. This is the intellectual center of the world. If you’re in Rome and your tutor didn’t train in Alexandria, then he’s a hack job, and don’t let anyone tell you different.

Cleopatra has all this at her fingertips, and lives in a society where it’s cool for royal women to know things. Not just royals, but women in general: Alexandria is home to lady doctors, painters, poets. You don’t even have to be noble to get an education. We talked in another episode about a woman named Agnodice, who came from Greece to Alexandria so she could train to be a doctor, then practiced secretly back home even though she wasn’t allowed. While Romans tend to think women are at their best when they’re quiet, barefoot, and pregnant, Egyptians like an educated woman: you know, as long as she doesn’t cause too much trouble.

Cleopatra is probably studying math, geometry, and astronomy, and knowing her dad, there are probably some music lessons thrown in there. She’s reading the classics and memorizing epic poems. Imagine her sitting on the palace steps, reading Homer’s The Iliad in the original Greek. Her tutors make sure to instruct her in rhetoric: how to persuade, convince, and manipulate someone into seeing your side of things. She seems to take a shine to languages: Plutarch tells us she speaks Greek, of course, and Hebrew, plus the languages of the Medes, Parthians, Arabs, Syrians, Troglodytes (a word that in Greek means “cave dwellers”), and an Ethiopian language that Plutarch says is “like the screeching of bats.” She’s apparently the only one of her siblings who bothers learning native Egyptian: the same language her 7 million subjects speak. She must know the power that comes from being able to communicate directly with the people, whether they be Macedonian or Egyptian. I hope she occasionally wanders out into the city in disguise, all Jasmine like, and eavesdrops on all the shit the locals are talking.

Greek writer Plutarch, like pretty much all of our sources, never meets Cleo – he won’t be born until around 45 CE – but he still has lots to say about her, including how lovely she is to listen to:

“It was a pleasure merely to hear the sound of her voice, with which, like an instrument of many strings she could pass from the language to another; so that there were few of the barbarian nations that she answers by an interpreter; to most of them she spoke herself.”

A word on Cleo’s looks. We have MANY pieces of art that depict her, but the truth is that we don't know what she looked like. And though the shade of her skin seems to be a bone of contention, it’s unlikely that she was a woman of color in the Egyptian sense. Being from Macedonian Greek stock, she probably has an olive complexion, and very little - if any - African descent in her family tree, though of course it’s a possibility. It’s telling that the most potentially accurate portrait we have of her is from the coins she minted. On them, she looks precisely nothing like Elizabeth Taylor: prominent nose, exaggerated features, and a very manly Greek look. But this is a coin we're talking about, which in the ancient world is a powerful piece of propaganda, with all the hallmarks of an Egyptian ruler trying to make herself look imposing to solidify her power. So we’ll just have to use our imaginations.

This is my little image to Cleopatra, which you can get on greeting cards or as a wall hanging in my Etsy shop. The pictured marble bust of Cleopatra comes from the Altes Museum Berlin.

Plutarch insists that Cleo isn’t beautiful. Instead, he writes, her bearing is…

“ ...not in itself so remarkable that none could be compared with her, or that no one could see her without being struck by it, but the contact of her presence, if you lived with her, was irresistible; the attraction of her person, joining with the charm of her conversation, and the character that attended all she said or did, was something bewitching.”

In terms of her level of power, we don’t know if she’s being groomed to be pharaoh. Given that she’s not the first born or a man, it’s unlikely. But she’s groomed for pharaohdom anyway: with the Ptolemies, you never know who is going to end up on top.

It’s worth repeating that this Egypt is very different than the one we left Nefertiti and Tawosret in: even Cleo would have seen those women as ancient history. This country has been broken open, globalized and exploited by outsiders. As the breadbasket of the Mediterranean, the superpowers all around it see it as a prize jewel worth winning. One of those covetous powers is ancient Rome.

If Rome and Egypt had a Facebook relationship status, it would definitely be “it’s complicated.” Rome is the Mediterranean world’s greatest military power, and they’re insatiably hungry, gobbling up nations left and right. They’d LOVE to invade and run Egypt as a client state. But it’s too big to control, and they’re stretched pretty thin already. Plus, whichever individual general conquers it could turn around and use its resources to seize control of what is, right now, the Roman Republic. Better to make sure that whoever’s ruling Egypt is firmly on the side of Team Rome.

Ptolemy XII isn’t afraid to wave his Team Rome foam finger, since he inherited a land with crippling debts. A previous Ptolemy actually left Egypt to Rome in his will, which means it’s hard to shut Rome out completely. And in a family where someone’s always trying to steal your throne, it pays to have powerful friends. So like many Ptolemies before him, he looks to Rome for legitimacy, giving them troops and money in exchange for their support. For context, this is right around the time when our favorite threesome – Pompey, Julius Caesar, and Crassus – are causing trouble over in Rome. Ptolemy supposedly pays Pompey and Caesar six thousand talents – it’s hard to translate what that would mean now, but we’re talking crazy money – to be his friend. The Alexandrians don’t like how chummy he’s being with these outsiders, and the city’s population isn’t afraid to stage a good old-fashioned riot. Which they do. Auletes is like, “shit, everybody. I just wanna play my flute. Is that so wrong?” And then he goes too far. The Romans take over the island of Cyprus, which Ptolemy’s brother rules, and he doesn’t stop it. His brother kills himself rather than give in to the invaders, and it royally pisses everyone off.

So they kick Auletes out, and he and a teenaged Cleopatra flee to Rome. At least we think she does. She might stay in Alexandria. Like so much about her life, it’s unclear.

Either way...the throne is empty, ya’ll. Let the Games be ever in your favor! Big sister Berenice ends up nabbing the prize. It turns out that the Egyptians dislike Ptolemy XII so much that they’re willing to have a teenage girl at the helm. But she’s a woman ruling alone, and we all know that won’t do, so her loyal followers pressure her to marry someone ASAP. One of her brothers would be best, but they’re really young, so she lets the people choose for her. The chosen suiter is a prince from the massive Seleucid Empire in what is nowSyria empire, and whose name is – inevitably – Seleucid. But he must be either really boring or flosses in bed, because within a week she supposedly has him strangled. Boy, bye! Next up is Archelaos from Anatolia, who fares better, but he has about as much power as the pool boy who fans her face with a palm frond. Berenice is running the show.

PAPPA ROME

Meanwhile, over in Rome, Ptolemy isn’t holed up in an Air B&B eating his feelings. He’s “petitioning” (*cough* bribing *cough*) anyone who will listen to help him take back his throne. If Cleopatra is with him, she’s getting a serious lesson in how to market yourself AND bribe with abandon. Dad plasters posters around the Forum and Senate (“vote for me, I play the flute!”) and gifts people with fancy canopied couches – the ancient equivalent of a really cool Vespa. In fact, he’s so up in Rome’s business that in 56 BCE our pal Cicero complains that his suit has “gained a highly invidious notoriety.” Pompey actually put Auletes and Cleo up, and speaks on their behalf in the Senate – a favor that he hopes will be repaid someday in full. When 100 delegates from Egypt arrive to protest Auletes’ return to the kingship, he throws a hissy, poisoning their leader and either murdering or bribing the rest to leave town. Classy.

And so it is that, with a whole lot of palm greasing, Ptolemy marches back to Alexandria in 55 BCE, backed by a Roman army: the first to ever touch down on Egypt’s soil. As you can imagine, the Egyptians aren’t real thrilled about it. But neither are the Roman soldiers, who aren’t keen to brave the scorching desert for a flute-playing foreign bastard. We’re Rome, dammit. What are we even doing here?

One young, chiseled Roman officer is totally down; his name is Mark Antony. This currently 25-year-old up and comer will spend time in Alexandria once they take it back for Ptolemy. This may be where he first meets and has lusty feelings for a 13-year-old Cleopatra. Maybe she likes him too, or maybe she just briefly ogles his legs under his Roman armor. Who knows, but keep him in mind. We’ll be coming back for him later.

When Ptolemy’s secured the city, he’s like, “Bye, Berenice!” and promptly chops her head off. Nice, dad. And lucky Cleo probably gets to watch. Being a daughter of the pharaoh, she must wonder how many steps she might be a way from a similar fate. Some say Ptolemy makes her his co-regent at this point – and, thankfully, he doesn’t try to marry her. Dad clearly likes her, and she likes him: she’ll later add the word Philopater, or “Father-Loving,” to her official king name.

Five years later, Ptolemy XII must know he’s dying, because he writes his will, and in it he does something truly annoying. He declares that he wants Cleopatra and her younger brother Ptolemy XIII to be co-rulers after he bites it, and he puts them both under Rome’s “guardianship.” Which seems like a bad idea all around. Maybe he doesn’t think Cleo will be accepted without a man beside her; maybe he is hedging his bets in case one of them dies. Maybe he sees there’s just no surviving as an independent empire without Roman support—not anymore. Auletes officially calls them Theoi Neoi Philadelphos: “New Gods” and “Loving Siblings,” probably hoping they’ll also get married...which, eventually, they will. Yummy.

When dad dies of, incredibly, natural causes - winning! - Cleo takes the throne with one hand tied behind her back. She has to share the title with a brother whose team will, from minute one, be trying to get rid of her. Thanks a lot, dad. But at age 18, Cleo is ready to rule, and she has all the tools she needs for greatness. “Move over, bitches. I’m about to show you what a real ruler looks like.”

First, she works to get in good with the local Egyptians. With the sacred Buchis bull dead – an animal worshipped by a cult near Thebes in Upper Egypt – she sails with the new bull some 600 miles up the Nile to oversee his inauguration. In fact, she may have been the first Ptolemy to do it in person. These festivals are sacred moments when the Egyptian people get to see their gods and goddesses, to interact with the divine. And Cleo knows it. So she makes sure to present herself at many such religious ceremonies, where the people can see her doing the ancient equivalent of kissing babies – and looking like an absolute goddess as she does it.

Ptolemaic women have made an artform out of aligning themselves with this fierce goddess and lady of the Underworld. Isis is actually the Greek form of her name: in Egyptian it’s Aset, meaning “seat” or “throne.” If you’ll remember from our earlier Egypt episodes, she’s the one who uses powerful magic to resurrect her murdered husband Osiris, whom she gifts with a golden penis so they can have one last epic roll in the hay. The product of that union is Horus, the god upon high who protects Egypt’s royalty. She goes back a long way, to the Old Kingdom, but she really picks up popularity under the Ptolemies. Powerful, yet kind, Isis becomes popular even beyond Egypt, with cults popping up in Greece, Rome, and beyond.

Royal women going back as far as Arsinoe II take pains to associate themselves with this powerful goddess linked to healing, magic, fertility, and a potent kind of female power. Cleopatra goes so far as to claim to be her manifestation on Earth; in fact, I think she believes it wholeheartedly. If you’d been told from infancy that you were the child of a new god, you’d probably believe it too.

She also takes every opportunity to be like, "Oh, I’m sorry. Ptolemy who?”, claiming herself as sole ruler on a bunch of monuments, conveniently forgetting to add her brother’s name. He doesn’t feature on the flip side of her official coins, either. Ooh, BURN. Meanwhile, she’s taking a page out of Hatshepsut’s book and carving images of herself all over Egypt. “Who needs to kill their brother when they’re crushing that ancient Instagram feed?”

This is the Cleo we don’t often see: an absolute boss, both great at PR and at making sure her country runs smoothly. But she’s inherited a country in decline on a couple of fronts. The Nile isn’t flooding like it used to; people are starving; grain stores aren’t what they were. And she keeps stumbling over the issue of how to deal with Rome, whose generals are currently playing a bloody game of political musical chairs as they shift from a Senate-led democracy to one that crowns people Emperors for Life. How can she keep Egypt independent in the midst of Rome’s epic civil war between Caesar and Pompey? How to hold Rome at bay without pissing them off?

From here on in, Cleopatra is going to spend a lot of time trying to keep the wolves at bay: or, more accurately, in trying to tame them.

Egypt may always be going to Papa Rome to help settle their dynastic matters, but Rome is always sailing to Sugar Mama Egypt for supplies and money. This is the time period when Pompey and Julius are duking it out for who’s going to be Rome’s one true leader. It’s only a matter of time before one or both of them come calling, asking for ships and money and political backing. Who to choose? When Pompey’s son asks Cleo for troops, she gives them freely; Pompey is the one who got her dad those Roman troops, way back when. But the Egyptian locals tend to revolt when they’re hangry, and this move does not make her many friends. There’s also what she does when those Roman legions that once helped her dad out were recalled back to Rome. They refused to go, as they’d settled in and started families in Alexandria, and got so upset about it all that they killed the governor’s son who came to collect them. Cleo, thinking she’s doing a good thing, sends the soldiers back to Rome in chains. Again, Alexandrians are pretty unimpressed by so giving in to Rome’s whims, forsaking their own.

And don’t forget, there is Ptolemy XIII and his posse to contend with, who are more than ready to get rid of her at the first available opportunity. And then, in 48 BCE, they do just that. They press Pompey to officially claim Ptolemy XIII Egypt’s sole ruler. And Pompey’s like, “No prob. Because I mean, a woman in power? I'll take a hard pass on that.”

Cleopatra finds herself an exiled queen, fleeing the only home she’s ever known with no certainty that she’ll ever make it back again, or even that she’ll live to see another day. She heads to Thebes, then to Syria to try and figure out how to get her throne back. This is where young Cleo really starts to come into her own.

PART II

Last time, we watched her grow up in the city of Alexandria, amid both luxury, excess, and the constant threat of death by family member. When her pharaoh father fled Egypt, she went with him, experiencing Rome for the very first time. General Pompey and some of their other Roman friends helped dear old dad win back his throne from his other daughter Berenice, and then, years later, he did something unfortunate: he left Egypt to Cleopatra AND her annoying brother Ptolemy XIII, and then he ALSO put them under Rome’s guardianship. She ruled well for a while, but her brother’s advisors conspired against her. Now Cleopatra’s a 21-year-old exile. How will she find her way back to greatness? Grab a fetching cloak, a burlap sack large enough to get rolled up in, and a strapping male companion. Let’s go traveling.

BATTLE LINES DRAWN

It’s 48 BCE, and dear brother Ptolemy XIII and his advisors have just managed to kick Cleopatra out of Alexandria, exiling her to the desert and what they hope will be permanent obscurity. But she’s not about to sit around and pout about how unfair the world is. After fleeing through Middle Egypt, then Palestine, then Syria, this rejected royal gets busy. She spends a hot, dusty summer raising an army. I imagine her command of languages comes in handy here as she uses her epic powers of persuasion to recruit some (hopefully) loyal followers. When we picture Cleopatra, we often think of her lounging in luxury, but this isn’t her situation. She knows how to rough it when she needs to and is willing to go to great lengths—and suffer great discomfort. Cleopatra is an adventuress as well as a queen.

Knives out, she marches through the Sinai to camp in the eastern Delta. For a clearer picture of where she is, exactly, check out my map of ancient Egypt, which you’ll find in the show notes AND in my Etsy shop, if you fancy one to hang on your wall. Unfortunately, Ptolemy XIII and his team are ready for her with a 20,000-man force full of pirates and outlaws. They are stationed at a fortress in Pelusium, making it nie on impossible for her to break through. She is relegated to the red sands down the coast, where she paces and schemes. She’s outnumbered, which means she will probably lose a battle. But how to get around them and back into Alexandria? How to reclaim her throne and neuter her brother for good?

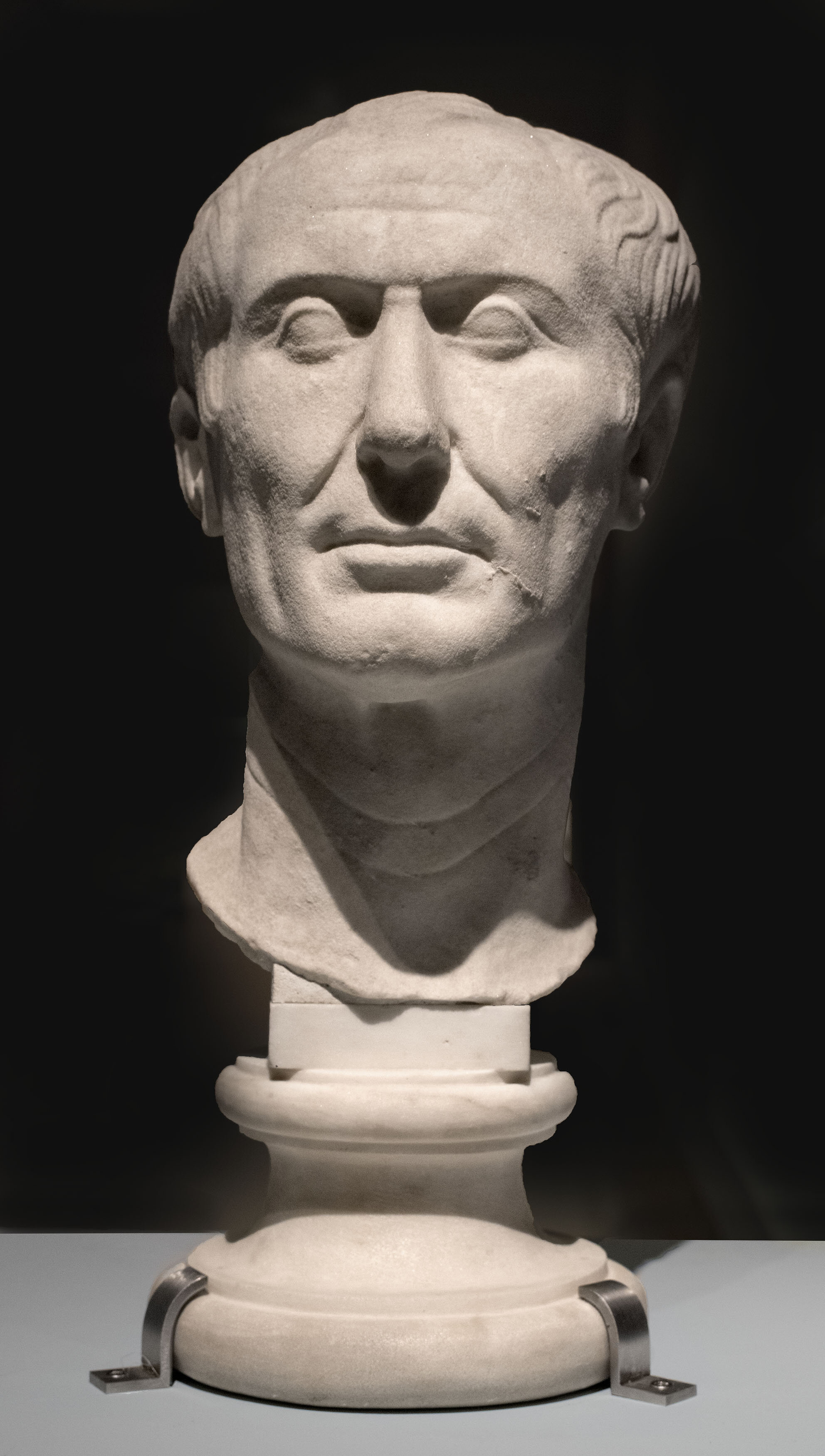

That's when fate intervenes in the form of Julius Caesar.

Julius is never afraid to toot his own horn.

A bust of Julius Caesar, Wikicommons.

As a reminder of where we’re at in Rome’s history: this is right around the time when the First Triumvirate is duking it out for who will control their home country. Right about now, the tide is starting to turn against Pompey the Great. This is the year he gets roundly trounced by Julius at Pharsalus. He limps off the battlefield to seek a place of refuge, and immediately thinks of Alexandria: I mean, he IS the only reason those Ptolemies are even on the throne, remember? Their dad loved him, and these kids owe him. So they’ll definitely roll out the welcome mat! What he doesn’t know is that Ptolemy XIII and his band of advisors are keenly aware that they need to stay in Rome’s good books, and they worry that in Pompey they have backed a losing horse. Should they try and make nice with him, as Ptolemy XII did, or should they side with Julius Caesar? Ptolemy isn’t sure. But his three main advisors – Theodotus, Achillas, and the eunuch Pothinus, are like, “Ugh, you know what? We’re overcomplicating this. Let’s just chop off his head and get rid of him entirely.” He’s too much of a danger. And after all, as Pothinus apparently says, “dead men don’t bite.”

Pompey lands just off of Pelusium, where he’s picked up in a small boat and taken to shore. He hasn’t even stepped onto the sands when a band of soldiers kill him while his entire force watches in their ships out in the waves. When Caesar arrives three days later, ahead of most of his troops, in search of Pompey, he’s gratified by his warm reception. But then, when Ptolemy XIII hands him Pompey’s severed head – surprise, you’re welcome! – it’s said that Caesar bursts into tears. Yes, so maybe it’s convenient that his enemy is gone, but this guy wasn't always his enemy: he was once his ally and his son-in-law. Caesar had it all planned out: he would forgive Pompey, and then they would march back to Rome arm-and-arm, uniting a divided Rome. But Ptolemy has robbed him of that future. So instead of pumping his fist and saying, “sweet job, Egypt!” he’s pissed. Ptolemy’s plan had blown up in his face.

And when Caesar looks around, he’s annoyed by the mess he sees in Egypt. He can’t afford for the Mediterranean’s breadbasket to explode in civil strife, especially when they still owe Rome a good amount of money. “What is this royal mess you’ve made, Ptolemy? Where is your sister? Ugh, you know what? Bring her back here. We’re all going to sit down and have a nice little chat.”

Young Ptolemy XIII has no interest in being commanded by Caesar, OR in seeing his sister back at the palace. Luckily, Cleo has plenty of spies in high places, and she gets word of the goings on anyway. Like all great leaders, Cleo recognizes an open door when she sees it. Julius is now Rome’s most powerful man; he’s currently mad at her brother; and he has troops, or soon will have. She has one chance to win his favor and woo him to her side, and she isn’t about to miss it. But if she isn’t careful, this door might just slam on her fingers. When and how to get to Caesar is going to be one of the most fateful decisions of her life. She could send a messenger to plead her case, but they could be intercepted or bribed. Sometimes, if you want something done right, you’ve gotta do it yourself.

She gets her loyal servant, Apollodorus, to sneak her back into Alexandria in a tiny boat. This isn’t an afternoon pleasure cruise. She has to navigate around some treacherous swamplands, then go the long way down South and up the Nile, past patrols and who knows what other dangers. It’s a trip of some eight days, and those days are very tense.Eventually Apollodorus rows her into Alexandria as the sun sets. But how to get in without anyone seeing her? She decides to pull her own version of the Trojan horse. Apollodorus rolls her up in a giant carpet, throws her over his burly shoulder, and carries her into the palace. Well, that’s how the legend goes. Plutarch tells us that “as it was impossible to escape notice otherwise, she stretched herself at full length inside a bed-sack, while Apollodorus tied the bed-sack up with a cord and carried it indoors to Caesar.” Some historians think it’s the type of sack one might have transported papyrus scrolls in, which is a nice image: papyrus scrolls are full of wit and knowledge, and you now what? So is Cleo.

Regardless of its exact dimensions, Apollodorus covers her with something and walks her right in, with none the wiser. “Scrolls coming through. Nothing to see here.” He has to take her all the way to the suite Julius has locked himself into, since the Alexandrians are now rioting outside the royal complex. Turns out they’re pretty pissed to see another Roman lording it over the Egyptian royal family.We don’t know if she’s actually unrolled in FRONT of Caesar. If your entire future depended on the impression you made on one particular Roman gentleman, wouldn’t you want a minute to freshen up and check your breath? Despite what most pieces of art will tell you, she probably isn’t dripping in jewels OR dressed in nothing but her lacy underthings, either. I mean come on, Renaissance painters…eyes up. In fact, it’s fair to say that she must plan this moment carefully, from what she’s wearing to every word she’s going to say. This secret meeting is a giant risk. She’s shrewd, adaptable, and knows a thing or two about rhetoric. Still, her heart must be pounding as she makes her way into his rooms.

Hey, Julius….

“Cleopatra and Caesar,” J. Jerome (19th century). Wikicommons

We have no idea what she and Julius say to each other, so let’s do a little creative scene setting.

C: *unzipping noise* “Heeeeeeey, Julius.”

J: "…oh damn, girl. How’d you get in here?”

C: “I lady never reveals her secrets. Listen: about this whole Who Should Rule Egypt business. I think we both know I’m the best person for the job.”

J: “Go on. I’m listening.”

C: “You want Egypt’s riches. I want to be the queen I was destined to be. Let’s be friends, you and I.”

J: “…political friends, for sure. But also…sexy friends?”

C: “…maybe.”

Does she charm him into bed with her sexy magic, poisoning his mind as Roman writers would have us believe? Perhaps. But arguing that she humped her way into Caesar’s good books does them both a huge disservice. As we’ve already learned, Caesar is a master seducer; there’s no WAY some horizontal tennis time with a pretty young queen is going to force him to do anything he doesn’t want to. And Cleo’s got a lot more going for her than the sweet delights of her body. There’s every reason to believe that she convinces him that allying with her is a good idea without resorting to such tactics. Though knowing how much Julius likes a strong, opinionated woman, we can imagine that he’s extremely impressed. “It was by this device of Cleopatra's,” Plutarch tells us of the unfurling carpet trick, “that Caesar was first captivated, for she showed herself to be a bold coquette, and succumbing to the charm of further intercourse with her, he reconciled her to her brother...” No matter how it goes down, this we know for certain: this exiled queen with everything to lose convinces Rome’s most powerful general that she’s the one he should throw his weight behind. I think if Cleo could sum it up, she might say: “I came, I saw, I conquered.”

To say that her brother Ptolemy XIII doesn’t take this well is putting it mildly. In fact, it’s said he runs into the street and throws a hissy fit, before promptly finding himself under house arrest. But from there, not all is smooth sailing for Cleo and Julius. Far from it. Not only are the Alexandrians angry about Caesar storming their city, but at Cleo for getting into political bed with him. Over the next several months, they’ll be trapped in the palace and fighting for their lives under a full-scale Alexandrian rebellion. And the Alexandrians are not to be underestimated. Cleo’s great uncle, Ptolemy XI, was once torn limb from limb in the streets because the people were mad that he murdered his wife. They subscribe to the ‘eye for an eye’ brand of justice. So her royal name is not enough to protect her, and Julius Caesar might not be either. They face threats both without and within.

Though Ptolemy XIII is under house arrest, his supporters are out there raising armies. Not wanting to be left out, Cleo’s younger sister, Arsinoe IV, sneaks out of the palace complex and helps lead a rebellion. Though the guy in charge of that rebellion, Achillas, gets mad because she has too many opinions. Ugh, men. No matter: Arsinoe kills him and takes over. The Ptolemy women do NOT suffer fools! Unfortunately, her troops ultimately betray her, turning her in in exchange for Ptolemy XIII, and she ends up a prisoner once again.

During all this madness, Julius and Cleo are trapped in the palace complex with nothing but his skeleton crew of 4,000 men—small beans compared to the rebel forces. He can’t get word out to try and rally reinforcements, so he and Cleo try to broker some peace. At a banquet they throw, they find out that some of Ptolemy’s advisors are planning to poison Julius and murder Cleo. Fights are taking place in the streets on the regular. Before long, they’re cutting off their supply lines, determined to starve them out. Julius’ men freak out because someone fills the palace reservoirs with saltwater. And Caesar’s like, “We’re Romans. Pull up your big boy pants and dig some new wells.” They even start erecting assault towers: how long will it be before they breach Julius’s defensive walls? At one point, with battle raging around the Pharos, he is tossed from his boat and almost drowns. In desperation, he has his troops set fire to his ships in the harbor: better that than have the enemy take them. This may or may not be responsible for burning down the city’s world-famous library. I can’t imagine Cleo is very psyched about that.

J. Caesar says: “Whoops.”

Burning of Alexandria’s port and surrounds, Wikicommons

She has to be anxiously biting her nails, wondering if she’s played her hand right. Have all her power plays been for nothing? Can she and Caesar pull this off? And yet it isn’t all bad news. If the Alexandrians are hoping to get Julius out of Egypt, all they really succeed in doing is pushing him and Cleo together. Turns out that she and 52-year-old Julius find plenty to do to pass the time on lockdown. Namely, lots of horizontal tennis! So…at least there’s that.Eventually some allies swoop in from Judea to help Caesar, and the climax of the so-called Alexandrian War takes places at the Battle of the Nile. Ptolemy XIII drowns there, rather conveniently, and Caesar finally puts Cleo where she belongs: on the throne. But not alone. You didn’t think we’d let a lady rule solo, did you? She’s crowned alongside her even younger, still-living brother Ptolemy XIV, whom of course Cleo marries. “…a mere pretence,” Dio tells us, “which she accepted, whereas in truth she ruled alone and spent all her time in Caesar’s company.”

Even when things calm down, Caesar doesn't sail straight home. Not even when Rome calls him up, all like:

*ring ring* “Um, hello? Julius? What you doin’?”

J: “Sorry, what was that? I can’t hear you – you’re breaking up…”

Instead he stays for months, eating figs and basking in his boo Cleopatra’s glory. It’s said they go on a pleasure cruise down the Nile together, taking in the Great Pyramids with many ships in tow. Why does he stay, when there’s no clear political benefit to doing so, and in fact perhaps some political harm? Roman poet Lucan says that “Cleopatra has been able to capture the old man with magic.” I say she’s captured him with her wit and many charms. Does he love her? He’s most certainly fascinated, and definitely infatuated. Does she love him? It’s hard to say, but I think she’s drawn to his strength and his power. Besides, they make a great team, and they want to show Egypt—perhaps the entire Mediterranean—that this power couple is not going to be trifled with.But all good things must come to an end. In 47 BCE, Caesar sails into the sunset, leaving Cleopatra with 12,000 legionnaires to protect her. He also leaves her with a VERY royal bun in the oven, whom she’ll give birth to not long after he departs. With her half-Roman son, Ptolemy XV Caesar – otherwise known as Caesarion – Cleopatra becomes perhaps the first Egyptian female pharaoh to use her baby-making ability to her own advantage. And she does it without giving up even one inch of her power.

Over in Rome, Julius has a big triumph to celebrate all the places he’s conquered. During it, he parades Cleo’s sister Arsinoe through the streets in golden chains. He then stuffs her in a temple and hopes she won’t cause any trouble. A Ptolemy princess, fading quietly into obscurity? Right, Julius. Good luck with that. He also starts making some reforms directly inspired by this time in Egypt, concerning a census and plans for a public library. He also reforms the unwieldy Roman calendar so that it more directly mirrors Egypt’s 365-day schedule.

Meanwhile, Cleo is left to rule Egypt in relative peace, with young Ptolemy XIV not much more than a royal seat warmer. But her regained position isn’t without its challenges. After the Alexandrian War, there are a lot of hurt feelings and rivalries at court, which means she has to do some housecleaning. And by that, I mean some executions.Like the rest of her family members, she grew up with a sense of herself as a goddess on Earth, and she isn’t afraid to act like one. She builds her image as a divine ruler through theater and epic pageantry, dressing herself up as Isis at every opportunity. She also gives money and favors to important priests, winning their devotion in a country where they are absolutely key. Like her ancestor Arsinoe II before her, she participates in festivals and holy rituals, always rocking her goddess outfit, and the people are LOVING it. But she doesn’t just rule from on high. She actually hears their grievances and helps settle disputes, helping to smooth out snarls between her subjects and her sometimes corrupt government officials. She takes the country’s debts in hand, devaluing the currency and introducing coins with different denominations for the very first time. Their markings determine their value, not their weight, and greatly help to regulate the economy. She and her massive governmental system control goods and services, making sure that money keeps flowing back to the crown. Take the brewing industry: Cleo makes sure that brewers operate only with a license and receive their barley from the state. And so Egypt’s most lucrative industries, from wheat and barley to papyrus, linen, and oils—are essentially royal monopolies. Cleopatra is only growing richer, raking in fully half of what the country produces. She commands the army and navy, negotiates with foreign powers, decides the price of goods and oversees the country’s agricultural plans. This is the Cleo we don’t often hear about: capable, savvy, thoughtful, and benevolent. A papyrus dated to 35 BCE calls her Philopatris, or “she who loves her country.” And she does it all while carrying, and then delivering, a child.

She must do a great job of getting Egypt running smoothly: enough so that, in 46 BCE, she feels confident to leave Egypt and sail for Rome with baby Caesarian in tow.

WHEN IN ROME (AGAIN)

We don’t know exactly why she leaves Egypt to fly into Julius’s arms. Maybe she really misses him; more likely, she wants to remind him that she exists, thank you very much, and introduce him to his child—his only male issue. She’s probably hoping he’ll name Caesarian his heir, making him the future ruler of both Rome and Egypt. It’s hard to say, but this queen is definitely going to make a splash.

We can only imagine her first impression of Rome, but it’s probably something like along the lines of “Ugh. Why does this place smell like pee?” As we’ve already explored, the Romans are great at building things like roads and aqueducts, but at this point, they’re not so renowned for their art or interior decorating. Rome is pretty ugly, at least at this point in history—rough and tumble and constantly under construction. Right now there is no Coliseum, no Pantheon. Compared to rich, colorful, sophisticated Alexandria, it won’t exactly make Cleo feel at home.

And the WOMEN. Rome likes its ladies quiet and subservient, at least in public, so this foreign queen, with her lavish gifts and entourage and the illegitimate son of their leader in tow, is bound to get tongues wagging. Cleo sweeps in like an ancient Kardashian: the public doesn’t want to look, but they just can’t help it. She even inspires a new Roman hairstyle that involves many braids. A trend setter, always.Julius seems happy to have her: he moves her into his country estate, on the west bank of the Tiber. No foreign royals are allowed in Rome, so it’s outside the city limits, but still a perfectly acceptable address. And thankfully it’s not the house his wife Calpurnia lives in, because…awkward. But Cleopatra’s position here isn’t easy. As good as she is with languages, she isn’t used to speaking Latin, and her biting wit and commanding presence must ruffle more than a few Roman feathers. In a world where women don’t get to choose their husbands and they’re supposed to keep eyes down in public, Cleopatra is very much out of her element, and there are men who resent her for it. As big-deal complainer Cicero will say later, though never to her face, “I detest the queen.” To which I’m sure Cleo would reply, “Boy, please. I don’t like you either.”

Though they’re sure to spend time together, Caesar’s away a lot, leaving her to fend for herself. Then in 44 BCE he’s made Dictator for Life. We talked about this in our episodes on Servilia and Fulvia, but to remind you, Rome is still a Republic at this point, and a lot of people are worried that Julius is getting too big for his breeches, acting all kingly in a land that is emphatically opposed. Julius already has a reputation for enjoying luxury a little more than a Roman leader should do. Maybe spending all that time with a queen and living goddess in Egypt gave him some poisonous notions? And she makes Senate members nervous. They can only imagine what she might be whispering to Julius over her wine glass during late-night dinners. “I mean really, babe. You’re not fooling anyone. You want to be a king, so…become one.”

All that said, this is definitely the wrong moment for Julius to commission a huge golden statue of Cleo and install it in a temple right beside one of the goddess Venus. And yet that’s exactly what he does! This is probably par for the course for Cleopatra, who grew up surrounded by statues of her family members. It is, after all, the Egyptian way. But the Romans are like, “Are you serious right now?” Because it’s one thing to worship a foreign queen in private. It’s quite another to publicly place her next to a Roman goddess while acting like a god yourself.

it was fun while it lasted.

“Caesar’s Triumph,” Peter Paul Rubens and Erasmus Quellinus II, Wikicommons.

That year, fearing where Caesar’s power is steering the Republic, some conspirators decide to stab him many times. We’ve covered this already, and so we know what happens: anger, finger pointing, fear, general chaos. But what of Cleopatra, who’s still in Rome when this happens? How must she feel when she hears of Julius’s demise? In a moment, she’s lost her lover, her powerful protector, and all of the security she fought so hard to win. And now she’s a foreign queen, with Caesar’s only natural son, in a city that’s as flammable as a barrel of gasoline. She knows when it’s time to make her exit. “OK, entourage, it’s time to BOUNCE.”

As 26-year-old Cleo boards her ship for home, she must be plagued by dark, troubled thoughts. If she was hoping for a loving future with Caesar, those plans are torn to pieces. If she wanted lasting security, that is nothing but tattered rags at her feet. And to add insult to injury, when Julius’ will was read aloud, she and her son feature nowhere in it. She thought she played the game so well, and now it seems like she’s back where she started: rich and powerful, but also vulnerable. And there may be a nagging question at the back of her mind, circling and painful: did her presence in Rome help bring about his death?Some sources say that when she sails away from Rome, she is pregnant, and has a miscarriage on the journey. That alone would be heartbreak enough. But she also knows that Rome is in chaos: how long before its generals start fighting for power, dragging her and Egypt into their squabbles? What if those powers see her son as a threat they have to get rid of? How long before the wolves start circling? How is she going to keep them at bay?

Next time, we’ll see Cleopatra cleverly navigate these very perilous waters. We’ll also see her strike up an alliance with another Roman general that will go down in history as one of the greatest love affairs of all time. We’ll experience lavish feasts, passionate love, savage murders, war, triumph, heartbreak. We’ll see Cleopatra reach her highest point, and then fall.

PART III

When we last left Cleopatra, she was creeping out the back door of a chaotic Rome in the wake of Julius Caesar’s death. As she sails the waves back to Alexandria, she broods over what might happen next. She’s just lost her Roman lover, ally, and protector, in a world where Rome is increasingly calling most of the shots. And then there is Caesarion, her son with Julius Caesar. In him, she has both a valuable advantage AND a potential danger. In some ways, she’s just as vulnerable as she was as a young exile. But Cleopatra is only now, a seasoned leader, and she isn’t one to sit back and let the gods take the wheel on her destiny. She’s managed to harness Rome’s powers in her favor and ensure her family’s continued legacy successfully before. And she can do it again—if she can just figure out how best to play the game.

GUESS WHO’S BACK

When Cleopatra arrives back home in Alexandria, she must be relieved to be back in her comfort zone. This is her city, her empire, and she knows her place in it. But she also has some fires to put out. Over at the temple of Artemis in Ephesus, Cleo’s sister Arsinoe is stirring up trouble, gathering up money and followers. They insist that SHE’S the real queen of Egypt. Also around this time, a pretender makes himself known in the front row, proclaiming that he’s Ptolemy XIII, returned. Surprise, everyone: you didn’t think I really drowned in the Nile, did you? To make matters worse, her 15-year-old brother-husband Ptolemy XIV is also becoming a nuisance. She’s facing potential threats on a couple of fronts here, and she hasn’t got time for petty Ptolemy infighting. So she nips the closest of these problems in the bud and has her brother killed, probably by way of poison. Ooh, Cleo. That is COLD. But this is just everyday business for the Ptolemies. Unsavory as it is, it’s nothing different than her forebears would have done.

With him crossed off the Future King list, she can do something she’s probably been dreaming about since she birthed him: install Caesarion as the new pharaoh. This achieves a couple of wonderful aims all in the one decision. First, it allows her to rule for him as co-regent without anyone trying to stop her. Because we’re fine with women leaders in Egypt, just so long as they have a man around as well! This particular man is only three years old, and her son, so he poses no threat to his mother’s way of doing business. She can feel that much more secure on her throne.And he’s a bit of a golden goose, this boy: the heir of Egypt AND a golden son of Rome. It’s right there in his official king name: “King Ptolemy, who is as well Caesar, Father-Loving, Mother-Loving God.” Subtle, Cleo! In propping up her son, she more firmly aligns herself with Isis in the Egyptian imagination: that powerful, much-beloved goddess who is also a mother who was willing to do anything for her family. She becomes even more of a godly creature, to be revered and respected. And in wrapping her son up in Caesar’s legacy, she’s reminding those who might try and challenge her—Rome included—that she’s got something they don’t. And she’s going to make sure that everybody knows it.For starters, she builds temples all across Egypt—like so many lady pharaohs before her, she knows the potent power of ever-present PR. She carves herself and young Caesarion into stone at places like the Temple of Dendera. There they stand in crowns, offering incense to Isis, her son Horus, and husband Osiris. That’s some powerful iconography right there. And she’s only getting warmed up.

larger than life.

Cleo and Caesarion from Dendera, courtesy of John McLinden (Flikr)

By this time, she may also have started building the Caesareum in Alexandria, a massive structure dedicated to her baby daddy right there in the harbor. She builds a giant temple to Isis, as well.She also spends a lot of time nurturing an intellectual renaissance in her city. Like the Ptolemies of old, she starts rebuilding her hometown as a place that learned people want to hang out and make merry. She starts a school of philosophy and fans the flames of a resurgence of scholarly works in areas like grammar and history. Medicine, too, sees a bump: under her reign, doctors produce new works on treating many maladies and new surgical techniques. She is credited with furthering studies in science, magic, and medicine. The Talmud says she had a “great scientific curiosity.” Roman men might want to see her as Caesar’s temptress, but at home she is a mighty scholar. Years later, she’ll be given credit for contributing new works on things like hairdressing and cosmetics. And though both claims come long after her death and are pretty dubious, it’s said she invents a great trick for keeping the skin young—bathing in asses’ milk, obviously—and a handy cure for baldness. Its key ingredients are burnt mice, burnt horses’ teeth, and bear grease. User discretion advised.

She’ll later get a rep in the Talmud for supposedly trying out experiments on her female prisoners to try and figure out when a fetus becomes an embryo, which sounds...pretty unsavory, and we can hope isn’t really happening. Especially since she becomes a patron of the Temple of Hathor, dedicated to women’s health.

So, stay in power: check. Produce an heir: check. But things aren’t all intellectual salons and fine perfume. In 43 BCE the Nile doesn’t flood, and Cleo once again has to deal with big-time plague and famine. She has to grant tax exemptions, devalue her currency, give out free grain. Still, when left alone to do her kingly business, Cleopatra proves herself a deft leader, well capable of running the show on her own. And yet, like a truly terrible ex-boyfriend, Rome just won’t stop calling her up. They’re currently back at war, and Cleopatra’s soon going to be forced to pick sides.

WHEN ROMANS ATTACK

Here’s what’s up with Team Rome right now. The studly Mark Antony – he’s baaaaaack – is now one of the top dogs in Rome. But so is Julius’s eighteen-year-old adopted son Octavian. They have temporarily joined forces to try and chase down Caesar’s killers, including Servilia’s son Brutus. This results in many battles, and everyone wants Egypt’s money and ships to give them an edge in the conflict. Cleo tries to stay out of it, but she finds she can’t ignore it. Not when one of Julius’s murderers, a guy named Cassius, tries to bully her into giving him some ships. She sends him her apologies, no can do, then sends her ships to a guy named Dolabella – remember him from our episode on Fulvia? But then one of her commanders goes behind her back to help out Cassius, who is an enemy to Mark Antony and Octavian. Later, she tries to meet those two at the head of her very own fleet, but it’s turned back by foul weather, and then illness. In the end, she just makes several men mad and makes friends with none of them. Suffice it to say it’s all a bit of a mess.But eventually Mark Antony and Octavian defeat the conspirators at the Battle of Philippi and become Rome’s #1 Heroes.

And then, after some very tense months of hating each other, they decide to join forces with that guy Lepidus and form the Second Triumvirate. Rome’s territory is now so big that one man can’t really manage it alone, so the three men split it up into chunks between them. Octavian will manage Italy and the West, Lepidus gets some of Africa, and Mark Antony, now truly at the top of his game, is given the whole of the East. He and Cleopatra are now on a collision course.And so this conquering hero decides to leave his wife Fulvia behind and go on a grand tour of his new territories. It’s basically the ancient equivalent of a lavish, long-term party bus.

This guy, who we’ll remember is intense, excitable, and loves a good party, stumbles into many different Eastern ports to great fanfare. He starts in Greece, where he hails himself as the New Dionysus. When he sashays into the city of Ephesus, he’s met by women dressed up as Bacchanalian revelers, the whole town wrapped in ivy. All the client kings and other Eastern royals are very much invested in trying to keep him happy. He is showered in attention, swimming in flowers with virgins thrown down at his feet. Some even offer up their own wives for his pleasure. He settles in at Tarsus, a city in modern-day Turkey, and his mind gets to wandering to that luscious Egyptian queen. He sends a guy named Dellius to call her to account for not supporting him and Octavian and maybe woo her a little if necessary. He says listen, I know you’ve been burned before. But Mark’s a great guy. You’ll love him.

But of course it’s Cleo that does all the wooing. She charmed the pants off of Dellius, who quickly realizes he’s dealing with a powerful woman who isn’t going to bend the knee for anyone. And he knows his boss Mark is going to be HELLA into that. And yet she doesn’t go to Tarsus. So Mark starts sending her texts through emissaries:

M: “Sup, girl. You up?”

M: “People say I look a lot like Hercules. I mean, that’s what I heard.”

M: “Yo Cleo, Mark again, just checking to see if you got my texts? Def not, because otherwise you’d already be here.”

Cleo chooses not to respond, or if she does, it’s with something like:

C: “Yeah, hey. That’s cool, but I’m super busy running a country. I just don’t know when I’ll have the time.”

She is always planning to go and see Mark, of course: she can’t afford not to. This isn’t the time to spit in Rome’s face. But she also knows the powerful allure of delayed gratification. And she isn’t some 21-year-old exile sneaking back into her country by night: not this time. There will be no slinking around in a burlap sack. No: this 28-year-old assured lady boss of a country is going to show up with more swagger than Beyoncé and more costume changes than a Lady Gaga concert. She must know him, at least by reputation: they’ll have met, either in Egypt or in Rome over the years, and his reputation is bound to proceed him. This is a guy who has been scooping up land and property along his way and handing it out to whoever flatters him the most profoundly. It’s a guy who loves to laugh, at other people and himself, and who is both charming and reckless. He LOVES drinking, good times, and a heaping helping of drama. And, of course, fancy women. He’s already slept with a few king’s wives on his epic Eastern party bus adventure. To win and then hold his attention, she’ll need to do much better. As Plutarch tells us, she knows it’s time to be “putting her greatest confidence in herself, and in the charms and sorceries of her own person.”

holla at me.

“Antony and Cleopatra” by Lawrence Alma-Tadema, 1884

A SEXY CLASH OF TITANS

So she sails toward Mark on the ancient world’s most opulent party barge, making one of the grandest entrances that history has ever seen. Shakespeare will describe this with his typical flair centuries later, but he won’t have to stretch his creative faculties to come up with this scene setting. Plutarch does that for him. He describes a boat with a gilded stern, silver oars, and purple sails. Music plays while colored smoke trails behind them:

“She herself reclined beneath a gold-spangled canopy dressed as Venus in a painting, while beautiful young boys, like painted Cupids, stood at her side and fanned her. Her fairest maids were likewise dressed as sea nymphs and graces, some steering at the rudder, some working at the ropes. Wonderous odors from countless incense-offerings diffused themselves along the river-banks.”

Cleo means to make a powerful impression, and she does it. You can almost hear Mark Antony’s jaw dropping. But I wonder if behind this careful staging, Cleopatra is anxious. The deal she strikes with this particular Roman general may have the power to change her country’s future. And she didn’t rush in with troops to help Mark when he and Octavian needed her: is he going to hold that against her now?

Cleo sends him a message, saying that Venus has arrived ready to party with Bacchus for the greater good of Asia. He responds by inviting her over for dinner. But she writes back saying she’d really rather have him over to her place. And he goes, because damn, this whole playing-hard-to-get-cuz-I’m-a-goddam-queen thing is working for him. He’s not single, but he’s most definitely ready to mingle. Over a series of several nights, Cleo proceeds to do what she does best and pulls out all the extravagant stops. She decorates dozens of banquet rooms with luxe couches draped with rich fabrics and decks out the trees with twinkling lights. Every table is laden with gold cutlery. One night she fills the dining room knee-deep in roses. At the end of each meal, she invites her Roman guests to take things home with them: furniture, horses, slaves. Whatever. But even more impressive than this display of Egypt’s many riches is the pharaoh herself. Ever the quick-witted chameleon, she swiftly reads Antony’s personality and moods and caters to them. When he makes crude jokes, she makes some of her own. Instead of trying to show herself above him, she meets him on his level. By the time she sails home just weeks later, their traveling romance has Mark completely smitten. Once again, Cleo’s got one of Rome’s most powerful men on the hook.

all the heart eyes.

“Meeting of Antony and Cleopatra,” Giovanni Battista Tiepolo, courtesy of the MET

Are they in love, or lust, or is this just politics? There’s no doubt that this alliance is important for them both. Mark Antony needs money and ships, both to deal with internal Roman problems and pursue his own ambitions; Cleopatra needs Rome’s support to keep her throne. Of course, ancient Roman writers would love you to think she uses dark, evil sex magic to addle this man’s senses. “The moment he saw her,” Appian tells us, “Antony lost his head to her like a young man, although he was 40 years old.” Another claims he’s under the influence of drugs when he falls so hard for her. Plutarch lays all of Mark’s mistakes to come at Cleopatra’s feet. He had faults before, but she’s really the one who ruins him, saying that “…now as a crowning evil his love for Cleopatra supervened, roused and drove to frenzy many of the passions that were still hidden and quiescent in him, and dissipated and destroyed whatever good and saving qualities still offered resistance. And he was taken captive in this manner.” But…come on now. He might be a good-looking Marlin Brando-type bruiser, with great curls and a hot temper, who has probably slept with more women than you could fit inside an Egyptian pleasure barge. But he is still an accomplished Roman general. Does Cleopatra completely have him in thrall? Yes, probably, but not just because of the charms of her body. She is smart, and an incredibly interesting woman to hang out with. She’s absolutely one of a kind.

Soon Mark Antony’s advertising his feelings by offing Cleo’s one remaining sibling. He orders someone to drag Arsinoe out of that temple in Ephesus and murder her right there on the steps. RIP, you almost queen! To give Cleo some credit, the priests there WERE proclaiming Arsinoe the rightful ruler of Egypt, and she knows that the threat will never die unless her sister’s done away with. And when the priests come before Mark and Cleo to beg for their leader’s life, she does ask Mark to spare him. That Ptolemy pretender doesn’t get the same courtesy. Mark has him executed, as well as that rogue naval commander on Cyprus—the one who supported Cassius behind Cleopatra’s back during all that Roman squabbling. But of course, every crazy thing Mark does from this point on is Cleo’s evil influence.