Augusta: The First Ladies of Imperial Rome, Parts I-II

A woman runs for her life through a forest. The air is choked with oily smoke and people’s screams.

Ash singes her dress as her husband grabs her hand, urging her to run faster, trying to get ahead of the flames. As she picks up her feet, clutching her baby more tightly, she wonders how she got here. She, the daughter of a prominent Roman family, married at seventeen, already a mother: the picture of a good Roman wife. And yet with one unwise choice, and not even her own, she’s became a fugitive and an exile. For Livia Drusilla, the future is looking pretty bleak. Little does she know that in a handful years, her life is going look very different. She will be married to Rome’s very first emperor, carving out a whole new path.

In this episode, we’re going to trace the paths of some of Rome’s first imperial superstars: the wives, sisters, and daughters who rose with Octavian to become ancient Rome’s first family, famous throughout the Roman world. Livia, Octavia, Julia, Messalina, both Agrippinas. In a time of great change, these women walked into the public spotlight and had to navigate both public love and hate in equal measure. They had access to power in ways that few women had before them, but to grasp it was a delicate and dangerous game. Who were these women, behind the rumors and the legends? How much influence did they wield and what mark did they leave?

Grab your purple stola, a laurel wreath, a sharp quill, and an even sharper tongue. Let’s go traveling.

livia’s image loomed large over the empire.

Livia and her son Tiberius, from Paestum and the National Archaeological Museum of Spain, Madrid. Wikicommons.

My sources

books

Caesar’s Wives: Sex, Power, and Politics in Ancient Rome. Annelise Freisenbruch, Free Press, 2010. This book formed the backbone for my exploration of many of these ladies.

Women’s Life in Greece & Rome: a source book in translation (second edition). Mary R. Lefkowitz and Maureen B. Fant. Duckworth, 1992. If you’re looking for a compendium of things said about and by women in Greece and Rome, look no further. For real.

Agrippina: Empress, Exile, Hustler, Whore. (UK/US editions are called by another name: Agrippina: The Most Extraordinary Woman of the Ancient World). Unbound, 2018. SUCH a great read!

Augustus. Pat Southern. Routledge, 1998. Available through Archive.org.

podcasts

The History of Rome by Mike Duncan was very helpful in painting Octavian’s side of the picture and boiling down the politics of his day.

Emperors of Rome, featuring our guest Dr. Rhiannon Evans, is a fount of information about the ancient Roman world.

“Livia Drusilla.” The Partial Historians.

online

“Livia: Princeps Femina.” Vroma.org. I also referenced their timeline for events in Livia’s life.

Cassius Dio, Roman History

Suetonius, Life of Augustus

Tacitus, The Annals

Macrobius, Saturnalia

“Femina Princeps: A First Lady of the Roman Empire.” McClung Museum of Natural History & Culture

“The Timeline of the Life of Octavian, Caesar Augustus.” San José State University.

“The Julian Marriage Laws.” UNRV Roman History.

“Livia Drusilla.” Donald L. Wasson. Ancient.eu.

episode transcript

keep in mind that I ad-lib and edit as I record, so this won’t exactly match the audio. All quotes left in bold were invented by me, so don’t use them in your history paper.

before you get going…

While you CAN listen to this episode all on its own, I think you’ll get more out of it if you listen to a few others first. Specifically, my three-part series on a day in the life of a woman in Rome will give you a lot of context about these womens’ everyday experiences; my three-part Domina series will introduce you to a lot of the political drama and power players we’re about to spend time with, sometimes in greater detail than we’ll get into here; and while you’re at it, my episodes on Cleopatra, much of whose story runs parallel to this one.

And as always, trying to find the women of ancient Rome is a challenge. They’re a flash in the pan – a bright light amid the long histories of the men around them. That means we’re about to spend time with Octavian, later called Augustus, and he’s a little bit of a spotlight hog. To understand and learn about women like Livia, we HAVE to talk about him…but we’ll try to shove him offstage as often as we can.

OCTAVIAN: “How dare you! I’ll have you know that I am incredibly interesting and important—”

Shhhhhhh, honey. Go to sleep.

octavian before livia

Speaking of…let’s introduce Octavian properly. We’ve met him briefly in several of our episodes already. He’s the young buck who joins with Mark Antony and Lepidus to form the Second Triumvirate; who defeats Fulvia in battle after writing rude poetry about her. He’s the one who ultimately defeats Antony and Cleopatra, bringing an end to an independent Egypt. He is Rome’s very first emperor, and perhaps its most successful. He stage manages his world as it morphs from Republic to Empire, setting a template for all emperors to follow.

I must admit that as impressive as he is, I’m not the biggest FAN of this guy. But let’s have his dating profile paint us a picture.

OCTAVIAN: Why hello there. I may not be much of a warrior, but in all other respects I am a king. Did I say king? I meant legend. I’m certainly as smart and crafty as my adopted father, Julius Caesar. I’m also GREAT at public relations and debate. I play a really mean game of chess, and I always play to win. My ideal woman is conservative, quiet, sweet, and obedient, and I abhor scenes and drama. Push me and you might just end up exiled to an island…and not the nice kind.

Ugh…swipe left.

Octavian and his sticky-outy ears, ready to take hold of an Empire.

Courtesy of the Museum of Fine Arts Boston.

So where did this guy actually COME from? He’s born in 63 BCE, just twenty miles outside of Rome, with the name Gaius Octavius. History calls him Octavius at this point, though his family calls him Gaius. His father, also Gaius Octavius, comes from the Octavii clan. They’re well-monied equestrians, but politically not all that distinguished. Dad’s the first among them to make it into the Senate, and he looks promising, until he dies when Octavius is only four. His mom Atia remarries, as a Roman matron is wont to do, a less impressive man named Lucius Marcius Philippus. He’s raised at least partially by his grandma, Julia Ceasaris, who just so happens to be Julius Caesar’s sister. He grows up with his six-years-older half-sister named Octavia. Remember her, because we’ll be coming back for her shortly.

It turns out that Octavius’s stepdad is cautious, and probably traveling nowhere politically. He’s definitely in the market for a male role model. Perhaps his great uncle Julius might fit the bill. But for now, Caesar’s too busy to take much interest in young Octavius. And it’s not like he shows any particular promise. He’s often sick, thin and frail, without any of the robust strength Romans are so fond of, and to top it off, he’s something of a mama’s boy. He seems smart enough, a good student, with some skill at speechmaking. He’s good at making friends that make up for his shortcomings. One of his school friends is Marcus Vipsanius Agrippa. He’s the bruiser on the playground, burly and brawny, and he’ll prove a good bro to have in Octavius’ corner. We’ll be coming back for him, too.

livia before octavian

In 58 BCE, while a five-year-old Octavian is toddling around, playing with blocks or whatever, Livia Drusilla is born. Her family, the Claudii, are much more distinguished than Octavius’. They boast Aeneas as their ancestor – you know, that guy who created the whole Roman race back in the day, or so they say. The Claudians have always been heavy hitters on Rome’s political scene: their members have seen some 28 consulships and six triumphs. No slouches up in here! Remember that in Rome, lineage is everything. It defines who you know, how you’re perceived, and how far you can go. And for women, it also defines your worth on the marriage market. When Livia comes of age, she’s going to be considered an extremely good catch. She grows up on Rome’s prestigious Palatine Hill, surrounded by the city’s most bright and shining glitterati. She grows up learning her duties: get married, don’t do anything scandalous, have babies, preferably male, and teach them well.

Speaking of duties, by 54 BCE, Octavia finds herself being married off to a guy named Gaius Claudius Marcellus. He’s a distinguished guy and goes on to serve as consul, but it turns out he’s not the biggest fan of his wife’s great uncle Caesar. When he came crashing across the Rubicon to take Rome, Marcellus stood against him. They’ve kind of made up, but still don’t like each other much. Some say that in 54 BCE great uncle Julius tries to pressure Octavia to divorce him so that he can marry her off to Pompey. You’ll remember him from previous episodes: that great general who forms part of the First Triumvirate with Caesar, and eventually has his head chopped off my Cleopatra’s brother Ptolemy. He’s just lost his wife, Julia, Caesar's only daughter, and Julius is keen to cut Marcellus out of the picture and tie Pompey back to the family tree. But Octavia pushes back, saying she doesn't want to divorce her husband. This causes some friction. But it also is the first sign we have that Octavia is loyal, steadfast, and not the wilting flower history tends to paint her as. It certainly won’t be the last.

Young Octavius doesn’t spend much time with Great Uncle Julius until 47 BCE. All his life, Caesar’s been a rising star. By this point he’s worked his way all the way up the political ladder, forming the First Triumvirate, conquering Cisalpine Gaul and beyond it, having a passionate affair with our friend Servilia, and marching his army right over the Rubicon River to claim Rome for his own. He’s crushed his enemy Pompey and spent some time over in Egypt, knocking sparkly boots with our main girl Cleopatra. He’s arrived home and been pronounced dictator, and Octavius is his closest male relative. Suddenly Octavius is closer to power than he’s ever been before.

He goes to Caesar and asks him for a favor: would he free his buddy, Agrippa’s brother, even though he fought in the war in North Africa against him? Caesar says no problem. Octavius earns a rep for loyalty, Agrippa’s Best Friends Forever bracelet, and Julius’ respect in the bargain. And so when he marches off to war some more over in Spain, he asks Octavius to come with him. Unfortunately he always seems to be coming down with something RIGHT before the fighting gets going. “*cough cough* I seem to have a terrible headache. No war for me today.” This will happen a lot in his career, earning him a reputation for cowardice. Is it the stress? Self-preservation? Or just a really compromised immune system? We don’t know.

But when he’s well enough, he and Agrippa head out by sea determined to get in on the action. They’re shipwrecked on the way and have to cross through enemy territory to reach Caesar. When they get there, it’s all done and dusted, but Caesar is touched, and it gives Octavius a chance to spend time with him at close quarters. They hang out in his tent, and when they head back to Rome they spend most of the travel time together. We don’t know what they discuss, but given how things turn out, Octavius clearly makes a huge impression. But when they get to Gaul, Octavius gets booted from his place with the arrival of Mark Antony. “Move over, bitch. I called shotgun. Who farted? Oh wait…that was me!” Ah, Mark, how we’ve missed you. Mark isn’t pleased to see this gangly youth in his spot, and Octavius can’t be overly pleased to be removed from it. Cue a rivalry that will continue for many years to come.

When they get back to Rome, Caesar rewrites his will. When he dies, three-fourths of his property will go to the young Octavius. He also posthumously adopts the boy as his son, making him head of the family and the heir to his title and name. Side note: the will stipulates that second in line for that honor is Marcus Brutus, son of his lover Servilia: the boy he loved like a son, and who will eventually murder him. You have to wonder if he writes this in partially out of love for Servilia, too. To prep Octavius for his future life, he starts to groom him, serving as a sort of assistant. He also sends him to Appolonia to learn oratory and swordplay. When he invades Parthia, Octavius will finally see battle beside him. His future is definitely looking bright.

sorry, caesar. party’s over.

“Caesar’s Triumph” by Peter Paul Rubens and Erasmus Quellinus II

life without caesar

But then in 44 BCE comes the news: Julius Caesar has died, stabbed by men of the Senate. It sends shock waves through Rome and well beyond. What now? His mom writes Octavius a frantic note saying to come home, but distance himself from the whole situation. His teachers tell him to command the legions in Appolonia and take Rome by force. He does neither, choosing instead to take his closest friends toward Rome to see what’s happening. Before he can get there, Mark Antony, all by himself and with NO coaching from his wife Fulvia…if you say so…gives a big speech over Caesar’s body, whipping the people into a frenzy and lying about what was in Caesar’s will.

When Octavius gets there, he finds out that Caesar has left him almost everything. Including his new adoptive title: Gaius Julius Caesar Octavianus. His mom can wring her hands all she wants, but Octavius is fully in the spotlight now. Some people – including his mom – advise him not to take the title. These are troubled and difficult waters for an 18-year-old. But he’s like, “Please. Don’t let these sticky-outy ears fool you. I was born for this.” And so even though an extremely jealous Mark Antony tries to withhold his inheritance and stall the adoption, Octavius becomes Gaius Julius Caesar, or as we like to call him at this point, Octavian. And this teenage hopeful is ready and willing to avenge his adopted father’s death.

livia gets hitched

Meanwhile, that same year – 44 BCE – Livia gets married. She is fifteen or sixteen, and Prince Charming is some 20 years older. “Oh, well. It could be worse .” Ah, Rome. Given the situation for patrician women, it’s likely this wasn’t a love match, but a family alliance. Remember that, as a woman, Livia is under the total authority of her paterfamilias: her dad gets to make all the decisions. Though in earlier times manus marriages were more common – this is where we see power over a woman passed from dad to new husband – by this period they’re a lot less common. Families like the Claudii want to keep family property and wealth intact, which means not letting family members become part of other families, legally speaking. So he’s likely the one who strikes the deal. And for a young girl in a society where marriages are political currency, she must know it’s entirely likely she’ll be married more than once.

How does Livia feel about it? Well, her suitor, Tiberius Claudius Nero, comes from another, not quite as distinguished branch of the Claudii clan, but on paper he’s fairly promising. As Cicero says, he’s a “nobly born, talented and self-controlling young man,” and he’s done a good job working up the political ladder. He even led Caesar’s fleet during the Alexandrian War: you know, that time in 49 BCE when Julius and Cleopatra were holed up in her palace, being shouted at by mobs and starved out by Cleo’s Alexandrian rivals. She has every reason to expect a prosperous union.

Of course, her first duty will be to have a son with her new husband. She’s young, so there’s every chance she’ll be able to do it. A Roman medical man Soranus will write in the 1st century AD: “one must judge the majority from the ages of 15 to 40 to be fit for conception, if they are not mannish, compact, and oversturdy, or too flabby and very moist.” And anyway, sex is good for us. As Hippocrates said in the fourth century BCE, women who don’t get married young and try for babies are more likely to suffer from visions and, sometimes, may even choke to death.

But what if she can’t conceive? Imagine, if you will, growing up in a society where you’re defined almost solely on whether you can make babies, particularly male ones. For a young Roman bride, there’s a lot of pressure here. And knowing how many women die in childbirth in ancient Rome, there must be a healthy dose of fear, too. Even so, it isn’t long before Livia gives birth to her first son.

She’s living on the Palatine Hill, which is THE place to be in Rome if you’re an influential mover and shaker. Cicero lives here, as does Mark Antony, as does Octavian. And amid this airy crowd, there will be a lot of pressure about how to raise her child ‘the right way.’ There seems to have been a fair number of wet nurses for the rich and influential, but also a certain amount of judgment of those women who don’t nurse their own kids. As the conservative philosopher Favorinus will tell us: “What sort of half-baked, unnatural kind of mother bears a child and then sends it away…or do you think that women have nipples for decoration and not for feeding their babies?”

A biographer writing years down the line will say that apparently Livia brings in a wet nurse, his judgy implication being that maybe if Livia had nursed her son Tiberius, he wouldn’t have turned out to be such a sucky emperor! “What can I say? This is what historians do with powerful women. Haters gonna hate.” What we can be sure of is that Livia takes pride in her son and wants to do as well as she can by him. Livia’s just your average wealthy matron: having babies, and trying to keep them alive, and running her household to the best of her ability. But soon enough, she’ll find herself one of Rome’s leading ladies.

But before we get to that, there’s a podcast I want to introduce you to, produced by none other than our friend Livia – or rather, the person who’s bringing her to life.

choosing sides

In the wake of Julius Caesar’s death, things in Rome are…shaky, to put it mildly. No one’s totally sure what will happen and who is running the show. In 43 BCE, after some skirmishes and heated exchanges that have everyone on edge, the Second Triumvirate comes together: an alliance made up of Octavian, Mark Antony, and a guy named Lepidus. We talked about this in our episodes about Fulvia and Cleopatra. This power threesome essentially comes together with one main aim: to annihilate Julius Caesar’s murderers.

And so Livia’s husband finds himself in the same boat as every other Roman citizen, having to pick sides between the men who killed Caesar to save the Republic and the men who have vowed to avenge their commander’s death. This is a battle not just for power, but for the Republic and its future. Choose the wrong side and it could bring shame, or even death.

For whatever reason, Tiberius Nero chooses to throw his lot in with Cassius, Brutus, and the other assassins. Livia’s dad does the same. That makes them enemies of Mark Antony, Lepidus, and Octavian. They’ve allied with the losing side, though they don’t know it yet. Does Livia back this plan, or does she just go along with it? How much sway or involvement might she have? Roman women can’t vote or serve in government, but we know they have an avid interest in it. They rally around political candidates, particularly family members, scrawling political graffiti on walls. In 42 BCE, right around this time, a woman named Hortensia delivers a speech protesting a proposed tax from the Second Triumvirate, which targets wealthy women, meant to help pay for their civil war against the assassins. We’ve mentioned this speech before, but it’s worth quoting again: “Why should we pay taxes when we have no part in the honors, the commands, the state-craft, for which you contend against each other with such harmful results?” Great questions, Hortensia. Her speech hits its mark, and the number of women subjected to the tax is lowered. But such a thing is an exception, not the rule when it comes to a woman’s power in the public arena. The Roman ideal for a matron is to be loyal, loving, and subservient - to know her place and to stay in it. Livia must know this. What can she do but go along?

At this point, it pays to reintroduce Fulvia, Mark Antony’s ambitious wife. It’s around now that, to drum up some badly needed cash for their cause, the Second Triumvirate starts a series of bloody proscriptions. This is where Roman citizens are put onto Naughty and Nice lists. If you’re one of the 2,500 to find yourself on the former, you’ll likely have your head removed and hung up on the rostra. The Second Triumvirate will take everything you own.

Livia has to see this happening. Do she and her husband hide in their basement every time the reapers come knocking? Do they spend every night wondering if it’s their last? Through it all, Fulvia is a powerful and influential figure. She refuses to help Hortensia when she comes to ask for her favor in fighting the tax law, and she uses the proscriptions as a means of getting rid of her enemies – bye, Cicero. She is a very visible actor in a way that women aren’t supposed to be. Livia must be aware of the vitriol the woman’s actions are inspiring. What does she think of it? “Well, I’m learning a lot of lessons about how to get men not to hate me. So I mean, I suppose that’s good.”

ON THE Road again

In 42 BCE, Octavian and Antony join together to defeat Julius’ murderers at the Battle of Philippi. Brutus’ ashes get sent back to Rome to his mom, Servilia, which is sad for her. Another sad thing: Livia’s father dies. Once he realizes his side is beaten, he does that thing so many Roman men think is noble and commits suicide in his tent. It’s exactly what Mark Antony will attempt to do twelve years from now in Egypt. But for now, he and Octavian are on top of their game. We can imagine that Livia is upset: her father killed not by some foreign enemy, but fellow Romans. An ominous sign if ever there was one. But with the death of her paterfamilias, Livia becomes sui iuris: independent in the eyes of the law. She could leave Tiberius Nero if she wants and join whatever side most suits her. But instead, she takes the more socially approved route of sticking by her man. Maybe it’s because she loves him. Or maybe it’s because Roman women are lauded for following their husband, regardless of where the political winds might take him.

So the assassins are dead. The question is…what happens now? Rome is fully under the control of just three men; that’s not a Republic, is it? Relations between the Triumvirs isn’t looking much more solid. After Philippi, things are tense between Octavian and Mark Antony. They are the ultimate frenemies, and Rome is about to suffer years of these two throwing mud at each other in an increasingly violent way.

So they do what all great Roman men do when they’re at odds: offer their female family members as bargaining chips. To that end, Octavian agrees to marry Clodia Pulchra, Mark Antony’s stepdaughter, whose mom is none other than our old friend Fulvia.

This is also the year that Julius Caesar is declared an actual god by the Senate: the first Roman citizen to be deified after his death, calling him deo invicto, or “the unconquered god.” This gets Octavian to thinking. If his adopted dad’s a god, then isn’t he divi filius, or the son of a god? And doesn’t that mean he’s meant to rule? The seeds of that whole “divine right to rule” idea are planted. But Rome’s not ruled by anyone solely…at least, not yet.

In 41 BCE, Livia’s main man Tiberius Nero decides things are getting a little too hot in Rome for his family. So he smuggles Livia and the baby over to Perusia in central Italy. Who should they run into but Fulvia. She is busy! By this point, Antony and Octavian are at odds again; Mark is off having a steamy affair in the East with Cleopatra. Octavian has insulted Mark and Fulvia both by sending BACK her daughter Clodia, saying that he’s divorcing her, sorry...but not really. “The marriage was never consummated,” he adds, “so was it even a marriage? I don't think so.” Fulvia and Antony’s brother Lucius get busy fomenting rebellion against Octavian, raising troops in Antony’s name. Fulvia has now made herself notorious for pushing her way into men’s business. In her open pursuit of power and influence, she breaks every one of Rome’s rules about a woman’s place.

What impression does she make on the young and vulnerable Livia? Is she impressed by what Fulvia’s trying to do in her husband’s name, or horrified? At the very least she has a front-row seat for the Perusine War she wages against Octavian. Her so-called “unwomanly” behavior reflects badly on her husband, becoming something that his enemies can use against him. And when Fulvia’s troops lose the fight, she sees Mark Antony essentially abandon her. Livia sees firsthand what happens to a Roman woman who tries to take what is seen as a man’s place. Perhaps she even vows that she won’t make the same mistake.

When Octavian – by which I mean Agrippa - attacks Fulvia’s camp in 40 BCE, they’re forced to flee in a chaotic retreat, and Livia and her husband are caught up in the madness. They spend the rest of the year moving from place to place, looking for someone to protect them. Eventually they end up in Greece, around Sparta, where the Claudian family has some sway. Fulvia dies in Greece after being yelled at and abandoned by Mark Antony, the man whose interests she fought so hard to protect. Meanwhile, Octavian and Mark are in the kind of awkward situation that can only be achieved when one guy’s wife raises troops and tries to overthrow the other. How to bury the hatchet on that whole Perusine War thing? Through marriage, of course…again. Octavian’s sister, Octavia, just so happens to be freshly widowed. No matter that she’s served less than the socially acceptable ten months of mourning! Little bro has political needs, and she’s the only one who can achieve them.

octavia saves the day

At the Treaty of Brundisium in October that year, Mark Antony agrees to marry Octavia. How does she feel about it? We have no idea. It’s hard to find the real Octavia behind the headlines of history. She is lauded as the angelic, sweet, and biddable wife of her era, held up as a paragon of female virtue. As Plutarch tells us, “they hoped that Octavia, who, besides her great beauty, had intelligence and dignity, when united to Antony and beloved by him…would restore harmony and be their complete salvation.” Everybody knows about his affair with Cleopatra, and many in Rome are made uneasy by it. Maybe marrying him to a proper Roman matron will be the making of him. If Octavia’s many stellar qualities weren’t enough to tempt the wild Mark Antony into better behavior, than no one can.

She has to know that she’s entering a complex political situation. But she has to feel happy that she gets to play an important part in cementing their alliance, becoming the glue holding their agreement together. Octavia’s often portrayed as a passive pawn and a frigid wet blanket. Shakespeare describes her as a “holy, cold, and still conversation.” But I think she has more fire in her than history allows. At this moment, she also clearly makes an impact on her new and headstrong husband. Not long after their wedding, Antony commissions some coins with himself and his wife on them. It’s meant to show unity between the western and eastern halves of Roman territories – Antony and Octavian, bros for life. But it also makes Octavia one of the first recognizable Roman matrons to show up on a coin while still living. There have been women on coins before, of course, in the eastern provinces, but never ones officially issued by the Roman state. The Senate would have sanctioned their making. Imagine if the American government decided to start printing Michelle Obama on five-dollar bills in 2020, visibly tying her with American currency and identity. In a time before the internet, coins are an important visual icon; a forceful symbol of status. This is new.

Octavia and Mark Antony rocking some coins the Roman state had minted. Way to be a big time star!

They swiftly have two children together – two daughters named Antonia Major and Antonia Minor. She dutifully raises them alongside Mark Antony’s two sons with Fulvia and her own three children from her first marriage. That’s seven children she’s raising, in case you weren’t counting. A regular Lucretia for the new generation. And for a time it seems like she really IS making a better man of Mark Antony.

Augustus also gets married in 40 BCE: for political advantage, of course. He chooses Scribonia, who is related to a guy named Sextus Pompeius. As you’ll remember from previous episodes, the original Pompey was part of Julius Caesar’s first triumvirate and a very successful general, until the Ptolemies over in Egypt chopped off his head. This Pompey, Sextus, is his son, and definitely not a friend of Antony and Octavian, and he’s been causing a lot of trouble, fighting and blocking grain from traveling into the city. So Octavian marries her to try and smooth relations, and before long she’s pregnant. Things are looking calmer than they have in a while.

But as Antony and Octavia sail off to the East, leaving young Octavian to try and rule a frazzled Rome, he yearns to cement himself more fully with the elite of his city. Caesar’s name won’t keep him on top forever, and one of the best ways of making alliances is through marriage. And so though he’s already married to Scribonia, those shrewd, ambitious eyes start to wander.

nothing like a little roman drama.

Roman matronae, Wikicommons

fates collide

So where is Livia? As part of the peace deal Antony and Octavian struck with Sextus, all the exiled families who backed him are given clemency, and also the chance of finally returning home. 19-year-old Livia and her husband are a part of that move. But as punishment for going against them, Livia’s husband only gets back about a quarter of his wealth and assets. Her husband’s career in politics is essentially over. This is where Livia and Octavian’s paths intertwine.

By the end of 39 BCE, Octavian has made a decision about his love life.

OCTAVIAN: “Scribonia, I think it’s time we threw in the towel here. It’s not you, baby, it’s me…well, no, it IS you. But…no hard feelings?”

He does this, by the way, just hours after she gives birth to his first child, Julia. Classy! Then he adds insult to injury by inviting a freshly divorced, pregnant Roman matron to move in with him. That woman is none other than Livia.

OCTAVIAN: “Alright, come on now. Hear me out.”

How and why does this even happen? How do they meet? What would compel them both to leave their spouses for each other? We don’t know, exactly. Octavian will go on to say that he divorces Scribonia because he can’t stand her constant nagging. As Suetonius puts it, he is "unable to put up with her shrewish disposition." Ugh, Octavian.

Other sources will say that he falls in love with Livia at first sight. Maybe he sees Livia at some dinner party and is like “Hot damn, I’ve gotta get me some of that.” And Livia’s like “heeeyyyyyy handsome.” Cassius Dio tells us that Octavian is so enamored of Livia that he starts shaving off his beard for her. Suetonius also gives us this little gem about Augustus’ beauty regimen: he used to “singe his legs with red-hot nutshells, to make the hair grow softer.” Alrighty. Tacitus, a critic of Octavian’s and writing way after the fact, paints a different picture. He says that Octavian is tempted by Livia’s beauty, and that he actively steals her away from her husband Tiberius. There’s a story from this period, taken from a letter that Antony writes Octavian, in which he insinuates that his rival seduced someone’s wife in the middle of a dinner party, returning her to the table with pink cheeks and some serious bed hair. He doesn’t SAY that woman was Livia, but it might well have been.

LIVIA : “A lady never tells.”

Other sources make it out like Tiberius Nero is totally in on the whole thing; they say he even gives his ex-wife away at her wedding. Of course, none of them say anything about Livia’s motives and whether she wants this marriage. I would kill for Livia’s super-secret diary on this whole situation, but we just don’t know what’s going on in her head here. Given that her father is dead and she’s legally emancipated, though, we can imagine that no one is cooking it up FOR her. It seems likely that it’s love for them both, at least in part.

No matter what Livia’s motives might be, it’s a risk. At this point, Octavian is not a universally loved figure, and Mark Antony is still powerful. What happens if Octavian doesn’t win the war for Rome? She might just be an exile once again.

Plus the whole thing is a little scandalous, because when they get together Livia is big and pregnant.

Dr. EVANS: “There were rumors that it might be Augustus' child. It was almost certainly adultery before they were married…there was a kind of tradition that after divorce, a woman would wait a year before remarrying, and it was instant. She divorced her first husband, Tiberius, and then married Augustus or Octavian pretty much the day after.”

On January 14, 38 BCE, Livia gives birth to her second son, Drusus. And then just three days later, she marries Octavian. Now THAT’s gonna cause a commotion. So why does this happen the way it does? We don’t know. But one thing is certain: Livia’s family lineage is something Octavian covets. The Claudiis are much more illustrious than his own family, despite their connection to Julius Caesar, and Octavian is a political animal. Love isn’t the only thing on his mind.

Despite the drama, newlywed life is pretty good. Livia might not have her two sons – by Roman law, they have to live with her ex-husband – but she does have plenty of money. And as a sui iuris, she manages her own financial affairs. She’s also the owner of several pieces of valuable property. And when her husband dies in 32 she gets full custody of her sons, Octavian will become their official guardian. Otherwise, we don’t know a whole lot about what these years are like for Livia. Her sister-in-law Octavia, though, is making some big waves on the public stage.

octavia saves the day (again)

By 37 BCE, the year after Octavian’s marriage to Livia, he and Antony are once again not loving on each other. Tensions between them are running very high. Octavia, pregnant with her second child by Mark, helps broker a peace between them by pulling a classic Sabine woman move:

OCTAVIA: “Please, don’t fight. I can’t choose between my brother and my husband! So you’ll just have to reconcile and hug it out.”

She’s hugely responsible for the Treaty of Tarentum, which renews the Second Triumvirate for another five years. For her role she’s called, as Plutarch puts it, a “wonder of a woman.” Mark Antony puts her face on MORE coins, portraying them as a happy and successful couple. That isn’t going to be the case for long.

From here, the boys part ways. Octavian goes to defeat that guy Sextus Pompeius, who has poked up his head to cause some trouble. But as we know, Octavian isn’t all that into warring.

OCTAVIAN: “*cough cough* my stomach hurts. I think I’ll sit this one out.”

Luckily, his best bro Marcus Agrippa is more than happy to ride in and score some victories for him. This military dynamo and all-around sexpot takes Octavian’s fleet in hand and defeats Sextus. Why HELLO, dashing!

Hey, Agrippa!

Marcus Agrippa, courtesy of the Louvre.

Meanwhile, Mark Antony is suffering from some real highs and lows over in the East. While Octavia is raising his many kids back home, he has a hot-and-heavy reunion with his old flame Cleopatra. They haven’t seen each other in a few years, but their connection is stronger than ever. This pharaoh queen gladly gives him money and troops so he can go and finally defeat the pesky Parthians. She even introduces him to his twins while she’s at it. No matter that his wife is one of Rome’s most popular matrons and his fellow Triumvir’s sister. He’s like, “Hold up, hold up: Octavia who?”

We don’t know how Octavia feels about her husband’s wanderings with a foreign queen, but if I had to guess I’d say: not so great. It’s one thing for your powerful Roman husband to have affairs in private. But in public, where everyone can see him? And with an Egyptian royal? It can’t feel good, to know that your husband is not only in bed with another woman, but in love with her. And she has to know that his growingly stubborn attachment is endangering his reputation in Rome, and thus hers as well. She could stay home and lie low, letting the chips fall as they may, but she doesn’t. Instead, in the summer of 35 BCE, she goes to Athens, gathers up some troops, supplies, and money, and sails out to meet him.

Plutarch tells us that she’s annoyed when she arrives in Athens to find letters from Antony, commanding her not to come any further, but she swallows it. But her approach still has a profound effect on Cleopatra. Plutarch imagines her being upset by the idea of, as he puts it, “Octavia coming to take her on in hand-to-hand combat.” Cleo clearly sees Octavia as a threat, and with good reason. For Octavia’s part, she might just see this as her last chance to win her husband back: to show him what they could be together, publicly and privately. To save her family from being ripped apart by the strife. But in the end, she’s forced to turn back and go home. When her brother Octavian, in all his self-righteous outrage, demands that she pack up the kids and move out of Antony’s house, she refuses. He might not want her, but that doesn’t mean she can’t stay true to the vows she made, standing by her wild and wayward man. But without meaning to, her steadfastness in the face of such effrontery makes Mark Antony look really terrible. As Plutarch puts it, her behavior ends up “hurting Antony without meaning to, because he became hated for wronging a woman of such fine quality.”

Octavian might well be mad about his sister’s treatment, but in some ways, Mark Antony is playing right into his hands. While Mark is off cavorting with Cleo, he gets busy creating an image of himself as just the right kind of man to lead Rome back to greatness. It’s a classic politician PR move, to promote himself as a model husband and brother – someone who can be loved and trusted. The women in his life are a HUGE part of that image making. He wants people to see them as modern-day Cornelias, loyal and brave and devoted to their family. And so he heaps them with honors women in Rome have never seen before. In 35 BCE, he gives them a protection called sacrosanctitas: something that only male politicians are usually given. No one is allowed to publicly insult them. They don’t need male guardians to travel around, either: while Vestal Virgins have this power, no other woman has ever been granted it. That means they can manage their own money and affairs without any male tutaila, or guardian. AND he starts putting statues of them up all over town.

This is a big deal, as Roman statesmen have long objected to statues of women in public places. Women aren’t meant to be honored in such a public way. The only real-life woman who’s ever had her likeness put up in the city is our friend Cornelia, although that was mostly about honoring her famous sons, the Gracchi brothers. Putting up statues of women, particularly while still living, is a potent statement that speaks to Livia and Octavia’s power. But it also puts them in the public eye, turning them into a new sort of celebrity, offering them up for scrutiny. Putting up statues of wives and sisters is something eastern kings do, and we all know how Romans feel about them. In this, Octavian has to move very carefully. He’s not pulling a Hatshepsut and throwing up images of his ladies with impunity: that would offend the traditionalists he’s trying to win over. So he makes sure these statues portray them as chaste, respectable matrons, a part of Octavian’s image as the man who will bring Rome back to a golden age.

things get ugly

Meanwhile, Mark Antony is doing the same type of thing, but in a totally different direction. He mints his own coins, but with Egyptian queen Cleopatra on them. He’s staging a triumph in Alexandria, gifting Roman-held lands to Cleo and his kids with her. Octavian and Antony write increasingly heated essays to and about each other, insulting each other for the world to see. In some of these, Mark Antony calls Octavian’s faithfulness to Livia into question, saying – and I’m paraphrasing here:

ANTONY: “You gonna get mad about me sleeping with Cleopatra? Really? I’ll bet by the time this letter gets to you, you’ll have slept with Tertullia, or Terentilla, or Rufilla, or Salvia Titsenia…hell, probably all of them.”

He reminds Octavian of times when his friends lined up a bunch of ladies for his inspection, stripping them naked so he could decide which one he liked best. In sum, he says, “Bro, do you even care who you stick it in?” Is this just political mudslinging, or is Octavian actually unfaithful? It seems from other sources that it’s likely the case. Octavian’s supporters, like Suetonius, says that sure, he sleeps with other women, but never out of anything so base as lust. He sleeps with other men’s wives and daughters to get important information and secrets out of them that will help move his career forward. So…that makes it fine!

In 32 BCE, things reach a breaking point between Antony and Octavian. Antony burns a major bridge when he officially divorces Octavia. Not even in person, mind you. He sends some of his troops back to Rome to let her know.

ANTONY : “Look, girl, you cute and all, but I think we both know this marriage is over. So how about you let my guys pack up all your shit and we move you OUTTA my house! Cool?”

How does Octavia feel about it? She doesn’t write anything down for us to ponder, but how would you feel if your husband broke up with you by text, sent while lounging in bed with his Egyptian girlfriend? Not great, I’m thinking.

Outraged, Octavian pries Antony’s will out of the hands of the Vestal Virgins and reads its contents out to the Senate. We talked about this in our Cleo episodes: how Mark leaves much of what he owns to Cleopatra and their children, and even says he wants to be buried in Alexandria. The whole thing shocks and horrifies the Roman men. This reading of another man’s will is illegal, by the way, but nobody cares, which is what crafty Octavian is counting on. It lets him do what he’s long wanted. He gets to declare war on Mark Antony…by declaring it on his Egyptian lady lover. How does Octavia feel about this? Not good, I’d imagine, though being a good Roman matron, she doesn’t say a word. At least not any that have come down through the years to us.

Fast forward to 31 BCE and the Battle of Actium, when Octavian’s main man Agrippa beats Cleo and Mark Antony. Cleopatra flees the battle, and Antony follows. Months later, Octavian arrives in Alexandria. Mark Antony kills himself, and Octavian holds Cleopatra under house arrest. Eventually she, too, commits suicide. It’s 30 BCE, and Octavian is now truly the last man standing. It isn’t clear what he’ll be to Rome now that he’s conquered, but he’s going to ride back into the city triumphant. How must Livia feel in this moment? Nervous, unsure, and maybe even excited. Because unlike her male relatives before her, Livia has finally picked the winning side.

We’ll leave our Augustan ladies there for now. Next time, we’ll find out what happens when Octavian returns to Rome and the Republic starts steering its way toward an Empire. We’ll see what role his ladies play in his rise, and what kind of power and influence they wield.

PART II

first ladies of PR spin

Back to Rome, 30 BCE. So now we’ve got an empress and everything is fine? Of course not. Remember that Rome has long loathed kings and feared them – that’s part of how Octavian got public support to war against Cleopatra, after all. And what is an emperor if NOT a king? We’re not about to make a clean or quick transition from Republic to Empire. In the wake of years of strife, no one can see exactly what Rome is going to become. Is the Republic just a dream, lost forever? If it is, then what path are we walking down now?

There’s no reason to expect the Roman people would be excited about suddenly having an emperor. But after about two decades of constant civil war, everyone is exhausted, tired of internal struggle, and more than ready to accept peace, law, and order. This is Octavian’s time to shine, if only he can spin it right. He is consul when he arrives back in Rome from Egypt; that’s the highest government position in the land, which is handy, as it means he’s already powerful. No need to make any sudden moves. But he can’t bank on being elected to that post over and over forever – others have tried it, and it never goes well. What he needs is a long game.

A big part of that game is to start building a myth around himself and his family: an image that will make him into a hero, related to the gods and Rome’s founding fathers, and one that looms too large to tear down. To that end, he hires a bunch of poets to sing his praises on paper. The real centerpiece is the epic Aeneid, written by Virgil, begun not long after he gets back to Rome. When it finally comes out, it paints his rise to power as not only great, but inevitable. How could anyone be in doubt?

In 28 BCE, Octavian and his main man Agrippa get busy restoring order. They start by annulling the laws that the Second Triumvirate put in place. It’s as if he’s trying to say: “The old Octavian is dead. I’m not a fighter anymore. I’m a statesman.” And in 27 BCE he makes a big move by renouncing all his king-like powers before the Senate, promising that he’ll restore the Republic to its former glory. This is sweet, sweet music to the Senate’s ears, who just want to keep their seats at the political table. In gratitude, they give him the name Augustus, “divinely favored” or “revered one.” This is what we’ll call him from now on. But Augustus himself makes sure everyone calls him “princeps,” instead, which means “first citizen.” They also ask him to stay as consul and serve as it more or less for life.

AUGUSTUS: “I’m just like you, see? No king here. But I am officially the boss of you. And you, and you, and you. Woohoo!”

Augustus is now on top, for real. But what about the ladies in his life – what do they get? Well, Octavia gets Mark Antony’s love children with Cleopatra. She takes in and raises their twins, adding them to the pile with the kids he had with Fulvia. Imagine that household, full of a raucous baby gang comprised almost entirely of your husband’s kids with other women. Sign me up! But she seems to do it willingly. In Rome, maternalism is deemed a natural female state, so good matrons are expected to raise children left motherless. Surrogacy and fostering are embedded in Roman ideas of womanhood. Rome’s mythical founders, Romulus and Remus, were once raised by a foster mother in the form of a she-wolf. So if she has the urge to complain, she keeps those feelings contained.

As for Livia, she’s not technically empress – there is no equivalent word in Latin, actually, and she won’t get the title “Augusta” for another forty years or so. Instead she’s called princeps femina, which is akin to ‘first lady.’ She’s perhaps the most exalted women in the whole of the Roman Empire, and she’s just stepped into a more public role than any woman before her. Her ascension marks an attitude shift toward women, too, seeing them as more capable, but also perhaps a greater threat. As our guest time traveler, Dr. Rhiannon Evans, says:

Dr. EVANS: “It seems to me that the imperial period is very, very bothered about women's behavior, that writers of the imperial period are really uptight about women. There are a few reasons for that. One of them is that in the Republic, men had had a lot more power…but because you have one man in charge in the imperial period, his household kind of has more influence… because the power is consolidated in one man, that power is, you know, it's overwhelming. And the women around him therefore have more influence and more authority.”

Part of what wins Augustus all that power is his promise to make Rome great again – to clean up the city with new buildings and better standards of living, but also to bring back the strong moral bar and ye olde family values that many think it’s lacking. To be that guy, he has to make sure that his family is the very model of propriety. Later in life, Augustus will warn his daughter and granddaughters not “to say or do anything underhand or which might not be reported in the daily chronicles.” He puts them up on a pedestal, giving them honors few women in Rome have known before them, but also a very long way to fall if they’re to stumble. Which, of course, some of them will.

dressing for the job you want

Augustus chooses to keep living in his house on the Palatine, rather than any kind of royal-type palace. Everyone knows where the first family lives, and so they are constantly on display. There’s wife Livia, of course, and his sister Octavia and her brood of miscellaneous children, and Augustus’s now ten-year-old daughter Julia. Like first ladies and prime minister’s wives in our era, these women would have very little privacy; everything they do is watched and marked.

In keeping with his conservative image, Augustus dresses frugally, as do his ladies. They don’t have time for lots of fussing over hair and makeup. He makes sure that everyone is fully aware that his wool clothes are hand-woven at home by the family. Weaving is considered the most honorable of matronly duties, so Augustus encourages the ladies to spend a lot of time doing it, making sure to put their looms by the large double doors so that passersby are sure to see.

Dr. EVANS: “...this is part of his story that she is weaving the clothes and the women of his household are weaving the clothes for him. Whereas, you know, what do you think? I think they had slaves doing all of that. And she did it occasionally as a kind of…to appear to be doing this. I think she played well into that narrative for him. And she apparently advised him a lot and he appreciated her advice.”

But this image of Augustus’ women flitting around in simple clothes, elegant pearls, and doing the Roman equivalent of baking chocolate chip cookies in full makeup doesn’t quite match up with the fact that they had hundreds of servants. A funerary vault discovered later will contain the remains of some ninety people who worked directly for Livia: hairdressers, doorkeepers, masseuses, window cleaners, and someone to set her pearls. Which makes total sense for the First Lady of Rome. Every outfit she wears will be scrutinized and scoured for meaning, which is why she needs at least two attendants to look after her ceremonial dress. We even know the name of one servant, Parmeno, whose sole job it is to look after her purple clothes.

Augustus, for his part, knows his wife is high value, and not just for her looks and skill at pretend weaving. But how much influence does she have on his politics? It’s hard to say. One thing we know is that, if she has an opinion, she isn’t walking around town freely voicing it. Livia has seen what happens to women who try to take the reins on their husbands’ politics. Sister Octavia knows it doesn’t pay to complain. So they stay behind the scenes, but that doesn’t mean they aren’t influencing the budding Roman Empire in a myriad of interesting ways.

For one, when Augustus goes abroad, touring Gaul and Spain, he takes Livia with him. It’s not the thing to take your wife with you on overseas trips, and the fact that he does speaks to two things: that he appreciates having her around, and that he sees her as an important aspect of his PR machine. Like the wife of a presidential hopeful, she goes out on the campaign trail, cutting ribbons and waving that killer first lady wave. She goes in style, with an army, a mule-drawn litter, and plenty of ladies in waiting. And she meets important women abroad, too, and bonds with them, creating further diplomatic ties between nations. Here’s some bonus episode crossover for you: remember the truly terrible King Herod of Judea and his sneaky, scheming sister Salome? Well when the Roman couple travel to Judea, she and Livia become fast friends, and will write letters to each other for the rest of their lives.

Livia clearly takes interest in many of the people she meets on these visits. Sometimes she even intervenes with her husband on their behalf. Take the residents of the island of Samos, who write to Augustus to say they want their independence from imperial control. He writes them back, declining, even though: “I am well disposed to you and should like to do a favor to my wife who is active in your behalf….” Years later, though, he changes his mind and grants them independence. Is this Livia’s doing? Maybe, but we’ll never know it. Livia knows better than to whisper in her husband’s ear where other people can see her.

On the home front, she continues to shine out as an example of chaste and upstanding womanhood, furthering Augustus’ image of his family as morally upright in all things. There’s a story about what happens when several men accidentally wander into her eye line while naked. Just a light bit of streaking through the Roman streets, boys? This is the kind of thing that can get a guy killed, but she spares their lives. “Boys, please. I’m so chaste,” she supposedly says, and I’m paraphrasing, “that naked men are nothing more to me than statues.”

And then there’s this. Augustus makes a habit of writing many of his conversations with people in a little notebook he keeps wrapped in his toga. That’s why we have this speech from Livia, advising her husband not to kill a man charged with conspiring to overthrow him:

“I have some advice to give you—that is, if you are willing to receive it, and will not censure me because I, though a woman, dare suggest to you something which no one else, even of your most intimate friends, would dare to suggest…I have an equal share in your blessings and your ills, and as long as you are safe I also have my part in reigning, whereas if you come to any harm (may the gods forbid), I shall perish with you…I give you my opinion to the effect that you should not inflict the death penalty on these men…the sword, surely, cannot accomplish everything for you…for people don't become more attached to anyone because of the vengeance they see meted out to others, but they become more hostile because of their fears…Heed me, therefore, dearest, and change your course…”

Does she actually say this? We can’t be sure, but Augustus wants us to think so. This reminds me of the custom, in far later centuries, of queens throwing themselves down at the feet of their kingly husbands to beg on behalf of someone else. Asking publicly for mercy so the king can show it without it looking like weakness. If true, it shows that Livia has a keen political mind and knows how to manage her husband. And she does it in a way that wins her praise and comparisons to Cornelia, that famously chaste model of Roman womanhood. But I have no doubt that Livia is a savvy negotiator, a persuasive debater, and a smooth operator. And I think Augustus loves her all the more for it.

Is it really love between Livia and Augustus? It’s hard for us to know. There’s powerful evidence in the fact that he never divorces her, when we know he has no problem ditching his ladies; they stay together for the rest of their lives.

Dr. EVANS: “He had no son. All right. So he had to keep adopting people. And in a lot of late Republican marriages, that would have meant instant divorce because you want to remarry. All right. The Romans are about monogamy. He can't be married to two women at once. So if he wants a legitimate heir, he'd have to marry somebody else. And he doesn't do that, which means that he saw some benefit in being married to Livia. And it must have been the advice she could give, her status (she comes from an extremely aristocratic family, which I don't think we can deny that that was important to him), that she must bring something to this relationship and to the huge revolution that he's engineering in Roman society that is worth maintaining. So there may well have been a lot of private affection between them, but she must be working for him politically too.”

Suetonius says that she is “the one woman whom he truly loved until his death,” despite his philandering. That same historian tells us that in his later years, Livia even helps procure attractive virgins for him, as he has a particular passion for plucking their flower. Oh my.

Someone interviewing her near the end of her life reports her saying that her influence with her husband was made “by being scrupulously chaste herself, doing gladly whatever pleased him, not meddling with any of his affairs, and, in particular, by pretending neither to hear or to notice the favorite that were the objects of his passion.” This sounds like something a lady only says when she knows her words are going down for posterity. But they suggest that, when it comes to PR spin, Livia knows just as well as Augustus exactly how to play the game.

a model woman

One of the things Augustus is most proud of is how he transforms Rome’s skyline. “I discovered Rome a city of brick,” he’ll later brag, “and left it a city of marble.” He makes sure a lot of those buildings and statues stand as testament to his might. One of these is the Portico of Octavia, a public colonnade named after his sister. Discoveries there lead us to believe that he had a statue of a goddess relabeled as one of Cornelia, the famous Republic-era matron, and put it in Octavia’s portico to link the two ladies together. Several more female-sponsored buildings follow. Livia makes her mark on monuments, too, most notably Augustus’ Ara Pacis, or the Altar of Peace. It’s the first state monument in Rome to feature women and children. Her hair is loose under her veil, making her look more like a goddess than a mortal. She and her husband are the only ones wearing laurel wreaths.

Dr. EVANS: “…we don't really have very many statues of women until this point. Certainly women who are still alive. And this is the first time that we have those public portrayals of women.…this is cementing their position as basically the royal family of Rome. So she's playing her part in that very effectively.”

These statues are kind of like the billboards of our era: they mean that everyone knows what you look like, and every curve and fashion choice is observed and emulated. They set a template for other ambitious women to follow.

Dr. EVANS: “…one of her legacies is in constructing this image that we can still see, because it's in museums all around the world, of a woman, you know, it's part of the Augustan makeover of that real beautiful classical look, which rejected all of that "let's try and look old" from the Republic. You know, old is respectable. Women having public statues, also not entirely respectable…and all the empresses after that they will have a public persona in that way. They know that their image can be displayed in public…they become part of the public consciousness, much more than women did back in the Republic. And Livia is the vital part of that transition.”

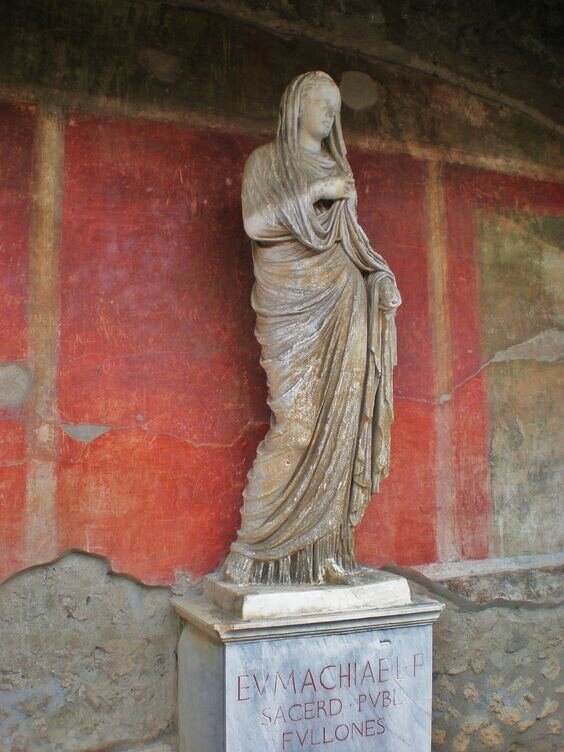

Eumachia’s statue in Pompeii, styled to mimic Livia, the Roman world’s most revered, trend-setting matron.

Wikicommons

In our episodes on a Roman gal’s everyday life, we heard about a woman named Eumachia. This daughter of a Pompeiian brickmaker marries into an influential family, then uses her new money dolla dolla bills to become a public benefactor, sponsoring all sorts of buildings. The Building of Eumachia was right in the city’s forum. It held a statue of Eumachia, dedicated by the fullers guild: you know, those people who clean our clothes with many things, including pee. Some scholars believe her statue was intentionally crafted to look like Livia. It’s like styling your hair after the most popular girl in your grade to be like, “see, I’m cool! I can totally rock tiny cornrows!” She styles her hair with Livia and Octavia’s traditional nodus hairstyle where the hair is parted in three, with the lower two sides tied into a bun at the back and the middle one looped up in a pompadour-like situation. This links Eumachia to the Empire’s most proper, respectable matron.

Dr. EVANS: “…her building in the forum even has motifs on it that clearly refer to an Augustine altar. So she is looking towards the imperial family as the kind of style gurus of the time. And almost certainly modeling herself on Livia and members of the Imperial family.…So then that's not a trivial thing, it's not just like the stuff you find in magazines. It is important that her influence is broader than just being contained within one household because she's got that kind of power.”

But Livia isn’t just showing up in public spaces in marble form. She is funding public buildings too, both religious and otherwise. She restores a temple of the Bona Dea, that mysterious female goddess we met in previous episodes. She builds the Macellum Liviae, a public market. But perhaps the most impressive in the Porticus Liviae, which turns into one of Rome’s top places to see and be seen.

Dr. EVANS: “Livia...she paid for, presumably, a portico right in the center of Rome, right beside one of the most important theaters of Rome. So a lot of people would have been congregating there and that's got her name on it.”

This isn’t a trivial detail: having your name on coins and buildings, in such a public space, means that people will recognize her and talk about her. They’ll say that she’s provided something for the public good. This kind of name recognition makes Livia an influential figure, and it reflects well on her husband. She’s playing smoothly into his myth-making game.

By this point, Augustus is doing some great things for the Empire. His slow and steady consolidation of power is going well. But the Julio-Claudians have a problem: they don’t have any kids together. Livia does deliver a baby, but sadly it’s born too early for ancient medicine to save. Every time Octavian gets ill, which is often, this issue weighs heavily on his shoulders: when he’s gone, who is going to carry on his legacy? What will happen to Rome if he’s no longer there to be its steward?

Rest assured he’s not going to pass his title down to his daughter Julia.

A section of the Ara Pacis, or Altar of Peace.

Courtesy of the Museo dell'Ara Pacis, Rome

AUGUSTUS: “A woman in charge? Please. Don’t be INSANE.”

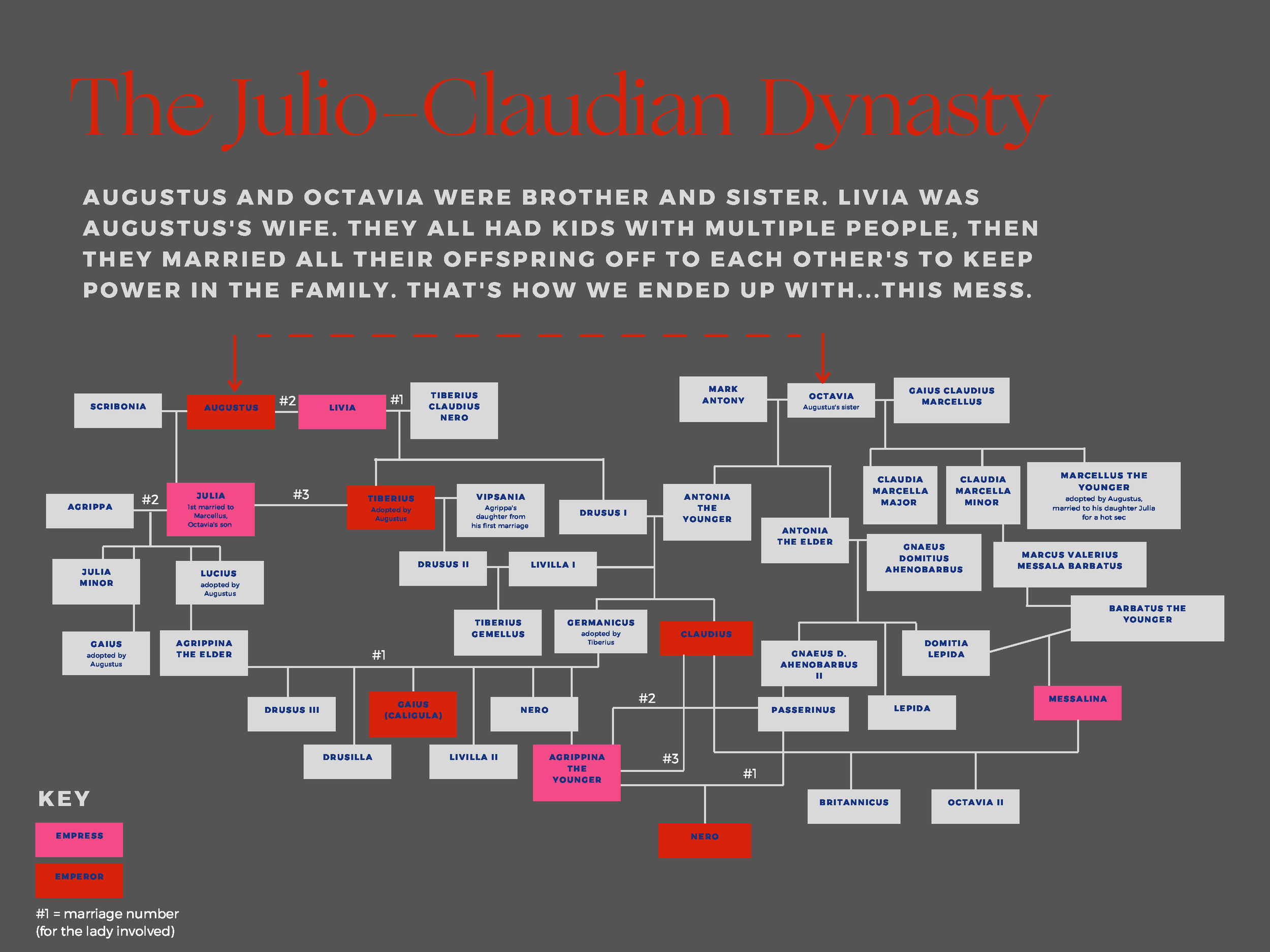

This is a good place to pause real quick and talk about the Julio-Claudian family tree, because it’s about to start getting confusing. I find that visuals help, so I’ve made a graphic for you and posted it in the show notes, but let’s try to boil it down audio style. It all starts with Augustus and Octavia: they form the tree’s two main branches. Augustus has one daughter, who we’ve already met. Octavia, meanwhile, has kids with several husbands. Livia has two sons, Tiberius and Drusus, with her first husband, and so they’re in the mix as well. To keep all the money and the power in the family, they swiftly start marrying their children off to each other’s. Throw in the fact that many have the same names and it’s easy to get lost, but I’ll do my best to guide you through it.

So who’re our candidates? There’s Tiberius Claudius Nero, Livia’s eldest son with her first husband. Livia’s lobbying pretty hard for that one. But there is also Marcus Claudius Marcellus, Octavia’s eldest son. The boys are about the same age; both were chosen to ride beside Augustus in his chariot during the triumphs after his return from Actium. But while Marcellus is cheerful of mind and disposition, Tiberius is pale and sullen. There’s also the awkward fact that Tiberius isn’t related to Augustus by blood. An adopted son, yes, and in Rome that matters, but so does biological family ties. So more and more, he leans toward Marcellus. In 25 BCE Augustus is like, “Hey, let’s marry Marcellus to my 14-year-old daughter Julia. They’re cousins, but that’s fine. Let’s keep it in the family!” Augustus is out of town when the wedding happens, so his studly buddy Agrippa steps in to give the bride away. A few years from now this is going to be…a little awkward. But before we get there, let’s meet Julia properly.

Talking ‘bout that tangled family tree! This is simplified - it doesn’t include every spouse, but the important ones in regards to the emperors’ succession.

daughter of augustus

We know very little about her childhood, but from what we’ll learn about her later, it’s clear she grows up outspoken, full of passion, wit, and fire. Macrobius tells us that she has a “love of letters and a considerable store of learning.” Given that the leading lights of the day are coming and going from her fancy house on the Palatine, it’s not all that hard to believe. She probably doesn’t mind all that public attention, though she can’t always love the judgement that comes with it. And having Rome’s first emperor as your father is constricting in the worst kind of way. He’s both incredibly controlling and, it seems, incredibly absent. “He brought up his daughters and granddaughters so that they even became accustomed to weaving and spinning and forbade them to speak or do anything except publicly that was not fit to be entered in the imperial diary,” says Suetonius. “He kept them from contact with strangers, to the point that he wrote to Lucius Vinicius, a noble and distinguished young man, that he had ‘behaved badly when I went to visit my daughter at Baiae.’”

Does she want to marry her cousin? Who knows, but when he says she’s to marry to her cousin, she has nothing to do but grin and bear it. He’s her paterfamilias - in some ways the father of Rome as well. At least she can count on it being a pretty lavish party. The first official imperial wedding makes Marcellus the heir apparent, Octavia the mother to the future emperor, and Julia its potential next empress. But it isn’t long before tragedy strikes. Just two years later, 20-year-old Marcellus dies. Augustus is devastated, but Octavia takes mourning to a whole other level. She will mourn her son for the rest of her life. She refuses to see anyone except her friend, the poet Virgil. In his poem Aeneid, there’s a scene where Marcellus’ ghost walks by as part of a parade of heroes. Apparently, Octavia is so overcome when she hears it that she swoons in Augustus’ lap.

Meanwhile, ugly rumors are swirling about Marcellus’ untimely demise. Angry that her son Tiberius was passed over, they say, Livia had him POISONED. A jealous woman behaving badly on emotional impulse? What a refreshing new storyline! The ancient world has never heard this one before! These rumors tap into a dark vein of the Roman psyche: the idea that because women keep the keys to the kitchen, they have the power to rip the family apart from within. We see it in the mythical stories of Circe and Medea, and we see it in the work of a Roman satirist, writing to sons to beware of their mothers: “…I warn you—watch out for your lives and don’t trust a single dish. Those pastries steam darkly with maternal poison.” A lot of people don’t believe the whispers, but a later writer, Seneca, makes it seem like Octavia does. She and Livia fall out badly after Marcellus’s death. Is it because she thinks Livia killed her boy? Because Livia thinks Octavia’s being totally extra with her grieving process? Or because they just don’t see eye to eye on things? Political or personal, we just don’t know.

We don’t know how Julia feels about her cousin-husband’s passing, either, but you know she ain’t gonna stay single for long. You’d think Augustus might give her hand to one of Livia’s sons, Tiberius or Drusus, but he decides to go in a whole other direction. Remember the strapping Marcus Agrippa who walked her down the aisle as a substitute dad? Yup: that guy.

Augustus loves Agrippa. He knows his best friend is the only man who can maintain the loyalty of the army. And he’s become so powerful at this point, his advisors warn him, that he’s either got to kill him or tie him to the Julio-Claudian line. So in 21 BCE, Julia marries him. Never mind that he’s 42 and already married to Octavia’s eldest daughter, Claudia Marcella Major. We can fix that. Apparently the ever-obliging Octavia gives her blessing to the match.

There must be something between the pair, as in their nine years together Agrippa and Julia have five children, turning them into the keepers of the Julio-Claudian dynasty’s future. They have two sons – an heir and a spare, if you will – Gaius in 20 BCE and Lucius in 17. Augustus once again skips over Livia’s sons in favor of setting his grandsons up as his successors, officially adopting them both just like Caesar adopted him. He’s clearly taken with the idea of grooming them. He puts their faces on coins when they’re just seven and four, with their mom Julia pictured beside them. Julia’s now the First Daughter he always wanted, being groomed as the future First Mother.

There’ll be another son and two daughters, Julia Minor and Agrippina Major. Don’t forget that last, because she’s going to feature prominently later. Julia often goes with her husband on his public tours, where she is much praised for her fertility and brood of cute, shiny children. Her life is looking pretty sweet…for now.

LAW AND ORDER

So: Augustus clearly has some strong and influential women in his family circle. So it’s interesting that, when it comes to women’s roles, he seems to want them as constrained as possible. Take his stance on women at gladiatorial games. “While formerly women had been used to attend gladiatorial shows together with men,” Suetonius tells us, “[the emperor Augustus] ordered that they could attend only if they were accompanied and if they sat in the highest rows.” So basically, Augustus sticks women in the nosebleed section. Thanks, bro! He gives Vestal Virgins special seats, but otherwise seems uncomfortable with the idea of women taking in the violent spectacle. Suetonius says: “He kept women away from athletic displays. Indeed, during the Pontifical Games he postponed till the following morning a boxing match that had been called for and issued an edict to the effect that women should come to the theater before the fifth hour.”

He’s all about promoting more conservative family values. So it’s no surprise when, starting in 18 BCE, he decides to turn that stance into a legal reality. The marriage rate in Rome is dwindling; people aren’t having babies like they used to; they’re spending too much time with their side pieces. In sum, there’s a sense that the Empire’s aristocracy is falling into moral decay.

Dr. EVANS: “…women are sort of blamed for what has gone wrong with the Republic. All right. So the Republic had fallen apart, had seen an extremely bloody succession of civil wars, lots of families just torn apart. And, you know, so much conflict. And the Romans really struggled to think about why when they were so powerful, they kind of imploded. And it's not just women, but certainly a big part of that. That narrative that the Romans told themselves of a state that has had everything and has fallen into luxury and become disaffected, is women's behavior. That women were acting in this very dissolute way.”

So he introduces a series of controversial laws, collectively called the Leges Juliae, or the Julian laws, meant to solidify the social hierarchy and preserve Rome’s class system.

Dr. EVANS: “…the two that were brought in the first time around are about, from my point of view, I think they're about constraining women and what they can do. So this is an attempt to...it's part of a kind of concerted effort by Augustus to show that he's doing something about this perceived problem…And he's completely effective with the spin.”

They are given some powerful incentives to have children, but if they break the law, they also bear the brunt of its most brutal punishments. Let’s break these laws down. To try and up the morality bar, they work to encourage legal marriage. Specifically, they make it mandatory for Romans to get hitched: Men between 25 and 60 and women between 20 and 50. If not, they have to pay higher taxes. Here’s a snippet from a charming speech Augustus makes about it in 17 BCE: “If we could survive without a wife, citizens of Rome, all of us would do without that nuisance; but since nature has so decreed that we cannot manage comfortably with them, nor live in any way without them, we must plan for our lasting preservation rather than for our temporary pleasure.” To which I imagine Livia muttering sotto voce: “Thanks, I guess?”

Under these new laws, all women under 50 are obligated to be married to someone. Imagine, for a moment, that you were required BY LAW to be married. In the first round of the law, those who get divorced have six months to remarry. Widowers have a year, and if a lady happens to turn down a proposal, they have exactly 18 months to find someone else. No pressure! Suddenly everyone’s on the hunt for young brides. Men aren’t allowed to marry underage girls, by which I mean girls under the legal age of 12 – yikes – but they can get engaged to one as young as 10, and often do to avoid paying these taxes.

Remember how we talked about a woman becoming sui iuris: independent of male control under the law? When Livia’s father died, her life was no longer run by a paterfamilias, but her husband has a certain amount of control over her life. But Augustus makes it so that if a woman has three children, she’s able to become legally emancipated, even if her husband is living. A baby bonus, if you will.

Dr. EVANS: “…so that's kind of a goal to go for, is if you've had three legitimate children, because his marriage laws were very much about trying to enshrine that model of the family, stop people committing adultery...This is what was wrong with Roman society, he thought. So clearly people wanted this. They wanted to attain this position of legal freedom. And that meant she could conduct business under her own name. You know, she had and the Romans are obsessed with legal business. They're obsessed with wills. She could do all of that and buy and sell, which Roman women, if they had property, they could kind of do anyway. But technically, it was always under guardianship…”

That means she doesn’t need a tutela, or male signatory, to conduct business, and that’s pretty powerful. Is Augustus doing women a favor here, giving them a path to greater freedom, or are these laws actually holding them back?

Dr. Evans: “It's very difficult for me to see the August marriage laws as giving women more freedom. I guess if you were in that space, if you were in that special position where you had had three children and they got you to that status, I mean, it's still very much dependent upon playing the Augustan game, as it were.”

Playing that game means having three children, in a time when having babies is a dangerous proposition, when you might be married to someone you don’t much care for, and many children die in their first few years of life, which isn’t counted. For women of lower classes, the rule is FOUR children. And just like in our time, there are women who can’t have children, or struggle to.

Dr. EVANS: “…even though the potential of this law is that women can achieve a degree of legal freedom if they've had the three children, I still think these laws are very restrictive on women. And I think they're mainly aimed at women's behavior.”

And there’s an even darker side to the law. Are you ready?

Dr. EVANS: “…if a woman is caught in adultery, and it is pretty much how it's thought of, then her husband has to divorce her. If he doesn't divorce her, then he can be prosecuted as a pimp because clearly if he doesn't care enough to divorce her, then that's what he's doing, he is pimping her out. He should divorce her and he will get most of her property or certainly she will lose at least two thirds of her property. And she and her lover are exiled to different islands.”

Two interesting side notes: you may remember from our When In Rome episodes that we talk about sexual relationships between men being totally fine in the Roman world view, except when those men are of different social classes, and the one perceived as the passive partner is looked down upon. This law makes it that “Anyone who has sexual relations with a free male without his consent shall be punished with death.” So that’s good, though you should note that it stipulates any FREE male. There is no punishment for having sex with a slave, male or female. So as per usual, they don’t make out very well…

It gets worse. If a father catches his daughter cheating on her husband under his roof, then he’s allowed to kill her and her lover. A husband, by contrast, can kill his wife’s side piece, but not his wife if he catches them. This makes sense when you remember that the father is the paterfamilias, or head of the family. But don’t worry: as the law states, “a husband who kills his wife when caught with an adulterer should be punished more leniently, for the reason that he committed the act through impatience caused by just suffering.” THE HARLOT MADE ME DO IT! Super compelling defense.

Not everyone is down with these harsh legal changes. Ovid, for one, spends years mocking Augustus. In response to the laws, he writes up tongue-in-cheek tips and tricks for women on how to secretly flirt with men at dinner parties without your husband catching you. There are also public demonstrations from those who want the law repealed. One includes a woman named Vistilia, who very publicly registers herself as a prostitute, she says, so she can avoid any of his adultery charges. And it seems that most people don’t actually dob people in or take advantage of the law’s harshest punishments. Most strive to keep their private business private, not wanting their family business called out in court.

Dr. EVANS: “In fact, we don't know of this ever being implemented at all apart from in two cases, which are Augustus's own daughter, and Augustus's own granddaughter, both of whom were called Julia. They were both exiled to islands and died there, in probably really awful circumstances.”