A Flapper Walks Into a Bar: The Iconic (and Fabulous) Woman of the 1920s

You lean over the speakeasy bar, beaded dress shimmering in the shifting light. It’s illegal to drink these days, but you wouldn’t know it from the merriment of the crowd around you. You wave to the barkeep and ask him for a Hanky Panky. He asks if you mean the cocktail, or…you know. Something else. You tip your head back and laugh, loud, not caring if it’s deemed unladylike. No one in this place minds a brazen woman; they love you. You wink at your date, who’s sitting beside you, and watch as your friends do the Charleston to the excellent jazz band. Their bobbed hair’s combed back in fetching waves, calves bared, dimpled knees flashing. Anyone who looks at you all will know you’re those girls they call “flappers.” The wild, uninhibited fashionistas setting America on fire.

Usually, we kick off our first episode of a new season by waking up in a new time and place and spending the day there. But this is the Roaring 20s: an era full of glamor and shimmer, petting parties and transgression, secret passwords and wild nights on the town. So we’re going to start by spending time with the most iconic lady of her age: the flapper. Bold, fun loving, independent, daring, shocking, the flapper might just be the most enduring icon of the 1920s. A woman who loomed large in the public’s imagination, capturing the spirit of the times. But who is she, exactly? Let’s have her introduce us to the 20s, and start to show us what life was like for ladies there.

Find out more about my debut novel, Nightbirds, at my author website.

If you like The Exploress, you’re going to love my magical girls.

Before we go traveling, I want to tell you that my novel, NIGHTBIRDS, is coming out extremely soon. NIGHTBIRDS is a 1920s-tinted YA Fantasy about a world with a Prohibition on magic instead of alcohol. In this world, there’s a group of girls called Nightbirds, who will gift you their rare magic with a kiss - for a price. It’s full of flapper-inspired dresses, magical cocktails, illicit speakeasies, nods to women’s history, and of course, a group of girls punching the patriarchy and getting into all sorts of mischief. It comes out February 28, and I would love it if you’d pre-order a copy. Pre-orders mean so much to authors: they signal enthusiasm to book buyers and publishers, and they all count towards a book’s first week sales, which can get books onto bestseller lists. You can also request it from your local library OR preorder the audiobook - I’ll be sharing an exclusive sneak peek with you soon. Find out more about NIGHTBIRDS on my other podcast, Pub Dates, which takes reader behind the scenes on the road to publication, at my author website, Kate j Armstrong dot com. Thank you for supporting my work.

Now: Pull on a beaded dress, bob your hair, and get ready to cause some scandal. Let’s go traveling.

Russell Patterson’s flapper illustrations in the 1920s were often featured in magazines like Vogue, The Saturday Evening Post, and Life. His illustrations contributed to the popular conception of the flapper.

My sources

Books/Academic Journals

Catherine Gourley, Flappers and the New American Woman: Perceptions of Women from 1928 through the 1920s, Minneapolis: Twenty-First Century Books, 2007.

Angela J. Latham, Posing a Threat: Flappers, Chorus Girls, and Other Brazen Performers of the American 1920s, Middletown: Wesleyan University Press, 2000.

Lucy Moore, Anything Goes: A Biography of the Roaring Twenties, New York: Abrams Books, 2010.

Judith Mackrell, Flappers: Six Women of a Dangerous Generation, New York: Sarah Crichton Books, 2014.

Emmanuelle Dirix, Dressing the Decades: Twentieth-Century Vintage Style, New Haven: Yale University Press, 2016.

Joshua Zeitz, Flapper: A Madcap Story of Sex, Style, Celebrity and the Women Who Made America Modern, New York: Crown Publishing Group, 2006.

Charlotte Fiell (Introduction by Emmanuelle Dirix). 1920s Fashion: The Definitive Sourcebook, London: Welbeck, 2021.

Lydia Edwards, How to Read a Dress: A Guide to Changing Fashion from the 16th to the 21st Century, New York: Bloomsbury Academic, 2017.

Ann Beth Presley, “Fifty Years of Change: Societal Attitudes and Women’s Fashions, 1900-1950,” The Historian 60, no. 2 (Winter, 1998): 307-324. https://www.jstor.org/stable/24451728

Ya’ara Notea, “The Mad Flapper: Socialization in Fitzgerald’s ‘Bernice Bobs Her Hair,’” The F. Scott Fitzgerald Review 16, no. 1 (2018): 18-37. https://doi.org/10.5325/fscotfitzrevi.16.1.0018

Megan Brady, “Feminism and Flapperdom: Sexual Liberation, Ownership of Body and Sexuality, & Constructions of Femininity in the Roaring 20’s,” SUNY Oneonta Academic Research (SOAR): A Journal of Undergraduate Social Science, 2019. http://hdl.handle.net/20.500.12648/1473

Annemarie Strassel, “Designing Women: Feminist Methodologies in American Fashion,” Women’s Studies Quarterly 41, no. ½ (Spring/Summer 2012): 35-59. https://www.jstor.org/stable/23611770

Joseph Collins, “Social Relevance of Speakeasies: Prohibition, Flappers, Harlem, and Change,” Senior Independent Study Thesis, The College of Wooster, Spring 2012. https://openworks.wooster.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?referer=&httpsredir=1&article=4819&context=independentstudy

Soo Hyun Park, “Flapper Fashion in the Context of Cultural Changes of America in the 1920s,” City University of New York Master’s Thesis, June 2014, accessed January 5, 2023. https://academicworks.cuny.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1262&context=gc_etds

Online Sources

Emily Spivack, “The History of the Flapper, Part 1: A Call for Freedom,” Smithsonian Magazine, February 5, 2013, accessed 12/21/2022. https://www.smithsonianmag.com/arts-culture/the-history-of-the-flapper-part-1-a-call-for-freedom-11957978/

Elizabeth Sholtis, “Shaking Things Up: The Influence of Women on the American Cocktail,” Virginia Tech Undergraduate Historical Review, July 23, 2020, accessed 12/21/2022. https://vtuhr.org/articles/10.21061/vtuhr.v9i0.4/

Lib Tietjen, “Let’s Get Drunk and Make Love”: Lois Long and the Speakeasy,” The Tenement Museum, accessed 12/21/2022. https://www.tenement.org/blog/lets-get-drunk-and-make-love-lois-long-and-the-speakeasy/

Heather Thomas, “Women’s Fashion History Through Newspapers: 1921-1940,” Library of Congress, July 20, 2021, accessed 12/21/2022. https://blogs.loc.gov/headlinesandheroes/2021/07/womens-fashion-history-through-newspapers-1921-1940/

Barry Samaha, “Shop the Looks from the 1920s That Continue to Inspire Today,” Harper’s Bazaar, November 29, 2022, accessed 12/21/2022. https://www.harpersbazaar.com/fashion/trends/g35335543/1920s-fashion-photos/

Marta Franceschini, “Flapper Style,” Europeana, December 11, 2020, accessed 12/20/2022. https://www.europeana.eu/en/blog/flapper-style

Ellin Mackay, “Why We Go to Cabarets: A Post-Debutante Explains,” The New Yorker, November 20, 1925, accessed 12/20/2022. https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/1925/11/28/why-we-go-to-cabarets-a-post-debutante-explains

Karina Reddy, “1920-1929,” Fashion History Timeline, May 11, 2018, accessed 12/20/2022. https://fashionhistory.fitnyc.edu/1920-1929/

“Prohibition Sparked a Woman’s Fashion Revolution,” The Mob Museum: Prohibition- An Interactive History, accessed 12/21/2022. https://prohibition.themobmuseum.org/the-history/how-prohibition-changed-american-culture/prohibition-fashion/

“Flapper,” Online Etymology Dictionary, August 18, 2020, accessed 12/21/2022. https://www.etymonline.com/word/flapper

Jonathan Walford, “What is a Flapper?” Fashion History Museum, August 30, 2021, accessed 12/20/2022. https://www.fashionhistorymuseum.com/post/what-is-a-flapper#:~:text=In%20%E2%80%9CEulogy%20on%20the%20Flapper,and%20went%20into%20the%20battle

“Flapper,” Green’s Dictionary of Slang, accessed 12/21/2022. https://greensdictofslang.com/entry/5mxnh3y

“History of Fashion 1900-1970,” Victoria & Albert Museum, accessed 12/20/2022. http://www.vam.ac.uk/content/articles/h/history-of-fashion-1900-1970/

Jen Doll, “How to Sound Like the Bee’s Knees: A Dictionary of 1920s Slang,” The Atlantic, October 19, 2012, accessed 12/21/2022. https://www.theatlantic.com/culture/archive/2012/10/how-sound-bees-knees-dictionary-1920s-slang/322320/

Moni Omotoso, “Haute Couture Designers Through the Ages: The 1920’s,” Fashion Insiders, July 20, 2018, accessed 12/21/2022. https://fashioninsiders.co/features/inspiration/haute-couture-designers-though-the-ages-the-1920s/

Katie Rudolph, “Historic Hair: ‘Bobbing’ and ‘Waving’ in the 1920s,” Denver Public Library, November 24, 2014, accessed 12/24/2022. https://history.denverlibrary.org/news/historic-hair-%E2%80%9Cbobbing%E2%80%9D-and-%E2%80%9Cwaving%E2%80%9D-1920s-1#:~:text=In%20general%2C%20women's%20hairstyles%20in,lie%20as%20flat%20as%20possible.

Emily Spivack, “The History of the Flapper, Part 4: Emboldened by the Bob,” Smithsonian Magazine, February 26, 2013, accessed 12/24/2022. https://www.smithsonianmag.com/arts-culture/the-history-of-the-flapper-part-4-emboldened-by-the-bob-27361862/

“1920s Makeup Trends,” Wardrobe Shop, August 7, 2019, accessed 12/24/2022. https://www.wardrobeshop.com/blogs/flapper-era/1920s-makeup-trends

“Party Patellas: The Knee Makeup Fad of the ‘20s and ‘60s,” Makeup Museum, August 21, 2020, accessed 12/24/2022. https://www.makeupmuseum.org/home/2020/08/knee-makeup-history.html

Jennifer Rosenberg, “What Is the Charleston and Why Was It a Craze?” ThoughtCo., July 27, 2019, accessed January 4, 2023. https://www.thoughtco.com/the-charleston-dance-1779257

Emily Spivack, “The History of the Flapper, Part 2: Makeup Makes a Bold Entrance,” Smithsonian Magazine, February 7, 2013, accessed January 4, 2023. https://www.smithsonianmag.com/arts-culture/the-history-of-the-flapper-part-2-makeup-makes-a-bold-entrance-13098323/

“Poiret: King of Fashion,” The Met Metropolitan Museum of Art, accessed January 5, 2023. https://www.metmuseum.org/exhibitions/listings/2007/poiret

“Brassiere: Flapper Style, 1920s Fashion,” Kent State University Museum, accessed January 4, 2023. https://flapperstyle.wordpress.com/black-silhouettes/brassieres/

Emily Spivack, “The History of the Flapper, Part 3: The Rectangular Silhouette,” Smithsonian Magazine, February 19, 2013, accessedJanuary 5, 2023. https://www.smithsonianmag.com/arts-culture/the-history-of-the-flapper-part-3-the-rectangular-silhouette-20328818/

Let’s paint our knees. Might as well, if we’re flashing them.

Citation: “Woman Paints Her Knees,” Messy Nessy, accessed February 12, 2023.

Transcript

Keep in mind that there might be typos in here: this is written for audio, and I don’t always catch them.

DEFINING THE FLAPPER

Let’s start here: where did the term “flapper” come from? It originated in the United Kingdom and can be traced all the way back to the 1570s. Back then, a “flapper” referred to a young bird or duck flapping its wings as it awkwardly learned to fly. It was sometimes applied to a young girl in jest to describe her flappy awkwardness. Some sources suggest there’s a connection to the dialectical term “flap”, aka, “a young woman of loose character.” By the 1890s, it had become a term to describe a flighty, emotional, or particularly wild young woman. A flattering etymological transition? Maybe not. This was the widely used definition that Wright’s English Dialect Dictionary published in 1900, when the word “flapper” made its way across the pond. Unsurprisingly, many Americans were confused by this odd British-ism, so much so that a 1909 New York Times article felt it necessary to define it. They said a flapper was “a young lady of debutante age (16-18) who, ‘has not yet been promoted to long frocks and the wearing of her hair up.’ In the early 1900s, it was still scandalous for anyone other than your husband to see you with your hair down, and only very young girls were supposed to do it in polite society. The flapper would soon burn this tiresome tradition to the ground.

The term “flapper” really came into its own after the First World War. A 1920s fashion writer described a “flapper” as a teenage girl whose awkward frame and posture required a long, loose type of dress to flatter her. But others, like the New York Timesdescribed her as something much more glamorous. A flapper was “the social butterfly type…the frivolous, scantily-clad, jazzing flapper, irresponsible and undisciplined, to whom a dance, a new hat, or a man with a car were of more importance than the fate of nations.” The flapper, and the heavy dose of judgment that seems to follow her, has officially arrived.

THE MAKING OF THE FLAPPER

But who IS the flapper? Where did she come from? She didn’t spring from the ether fully formed, chain smoking and swearing in scandalous fashion. Her existence was predicated on a number of social and cultural changes that took place leading up to the Twenties. Let’s talk about the forces that pressed us into the sparkling diamonds we’ve become.

As we shimmy into the 1920s, we have to remember that America has only recently emerged from an unprecedented and devastating war. World War I, or the Great War, as we call it, ended in 1918, and it was like nothing we’d seen before. It decimated much of Europe, shattered the optimism of the early century, and left millions of soldiers dead. There’s nothing like war to remind people how precious life is and to shake up old rules and ways of being. In the years before the war, women were discouraged from taking up professions. Many women had to work, of course, to make ends meet, but most people really wanted them to stay at home. But when the war came on, the government NEEDED them, and thus pulled a 180 and started encouraging them to do their part. Many seized the opportunity to take men’s places in factories and offices, working as nurses and ambulance drivers. When it ended, many hoped they’d sashay on back into the kitchen, but we ladies weren’t of a mind to give up the freedom that came with making and controlling our own funds. The war years, and the changes they brought, had transformed us. By the end of the 1920s, more than a third of American women were employed, including half the single female population. It’s quite a new thing to have so many women out of home, making their own money, and able to fill their leisure time as they choose to. In America’s big cities, there is ever so much to do.

Americans had been migrating increasingly from country to city for decades. Between 1860 and 1920, cities with populations of at least 8,000 saw their populace jump from 6.2 million to 54.3 million. Before the war, America was mostly a nation of farmers; by 1920, for the first time in the country’s history, more Americans lived in cities than the countryside. Women flocked to cities. A government-conducted survey from 1920 discovered that “the farmer’s daughter is more likely to leave the farm and go to the city than is the farmer’s son.” Why? Opportunity and independence. When asked why she left home for the big smoke, one flapper said that she “wanted more money for clothes than my mother would give me.…We were always fighting over my pay check. Then I wanted to be out late and they wouldn’t stand for that. So I finally left home.”

Many were their own mistresses, more or less, for the first time: some quarter to a third of adult female workers in cities were living solo in apartments or boardinghouses. This was a radical change from the Victorian and Edwardian eras, when girls tended to live with their families until they married. Now, suddenly, they had a way to get out from under the close and constant surveillance of their parents without having to tie the knot. A generation of young women had their own identity independent of their family, and they were going to make the most of it.

At the turn of the century, there was little in the way of nightlife in America. One had house parties or went to the theater, but after dark the streets became a scary place. George Foster, a writer for the New-York Tribune, cautioned his Victorian-era readers of “the fearful mysteries of darkness in the metropolis—the festivities of prostitution, the orgies of pauperism, the haunts of theft and murder, the scenes of drunkenness and beastly debauch …” Even big cities were dimly-lit places, with gas lamps that offered only a feeble, short-lived glow. In 1907, less than 10% of American households had electricity. By 1930, that’s going to jump to 68%. Electricity lights up streets and laneways, completely changing the rhythms of our evenings. For the girl in want of a little adventure, nothing glows more brightly than those New York City lights. Plus, electrical appliances in our houses mean domestic life requires less manual grind, which means more time for pleasure. We have more places to go, and a faster way to get there. The fairly newfangled automobile is more accessible than ever, and offers gals even more freedom. We have more access to travel, employment, and university education, and we’re finally voting. The New Woman has officially arrived[1] .

What is the New Woman (capital N, capital W)? She is someone who isn’t afraid to roll up her sleeves and get her hands dirty in the war effort. She is modern and educated, with a desire to get involved in public life and a career. She is unshackled from her mother’s laced-up Victorian ideals and ready to experiment with looser, even transgressive ways of living. No longer will she sit on the porch and let her parents guide all her life’s choices. She is going to make her own way. As famed anthropologist Margaret Mead wrote, “We belong to a generation of young women who felt extraordinarily free- free from the demand to marry unless we chose to do so, free to postpone marriage while we did other things, free from the need to bargain and hedge that had burdened and restricted women of earlier generations.”

But the 1920s made way for a new, more radical kind of New Woman: one who really took the whole notion and ran with it. Let’s meet the shocking, scandalous, and sexy bad girl of the Twenties. Watch out, world: here comes the flapper.

Joan Crawford as a flapper in her 1929 silent film, “Our Modern Maidens.”

WHO IS THE FLAPPER?

But what exactly IS a flapper? Let’s ask Zelda Fitzgerald, one of the women upon whom her imagine was crafted. Her literary husband, F. Scott Fitzgerald, wrote his debut novel, This Side of Paradise, largely based on his wild life with Zelda. It was dubbed “a novel about flappers, written for philosophers,” and it launched the couples’ celebrity status. Scott soon became known as the expert on flappers, despite the fact that his novel never specifically used the word. He spent years writing stories about the same image of youth, full of fast rides in cars and heavy petting sessions, of girls who smoked and drank and cut her hair short. The heroines featured in Scott’s stories were “uninhibited, freedom-loving, playful, and sexually responsive (but never promiscuous).” All were undeniably based on Zelda, one of the era’s most fabulous flapper poster children.

She feels that flapperdom is really about pushing against boundaries, refusing to settle into the mold that society sets for the ladies. She wrote in an article written in 1922: “The Flapper awoke from her lethargy… bobbed her hair, put on her choicest pair of earrings and a great deal of audacity and rouge and went into the battle. She flirted because it was fun to flirt and wore a one-piece bathing suit because she had a good figure, she covered her face with powder and paint because she didn’t need it and she refused to be bored chiefly because she wasn’t boring. She was conscious that the things she did were the things she had always wanted to do.”

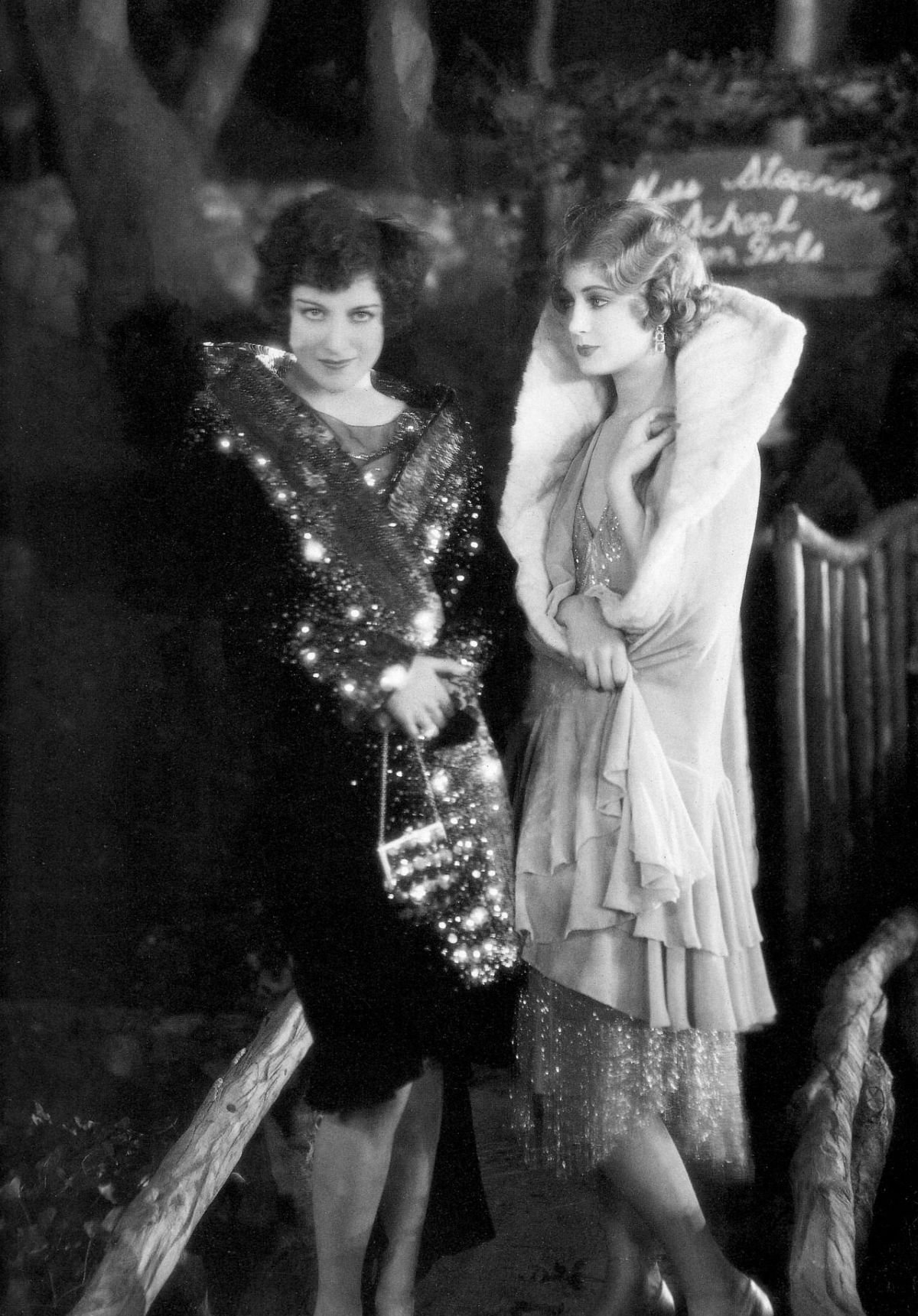

Magazines like Vanity Fair and Life took note, publishing endless articles about flappers, while Vogue and Ladies’ Home Journal obsessively cataloged their latest trends, which could be seen in New York boutiques and Iowa department stores. Advertisements, too, capitalized on the popularity of the flapper to sell everything from cigarettes to automobiles as savvy businessmen shaped her into something that could be branded and sold. The flapper would also become a staple of Hollywood. Meanwhile, the rising influence of silent films is giving the flapper an even more glamorous and tangible face. Films like the 1923 Flaming Youth, in which Colleen Moore captures the flapper in all her risqué glory, underscored the image of the flapper. Actresses like Clara Bow and Louise Brooks really glamorized the image of a girl with bobbed hair out with the fellas, drinking and laughing it up without care. “Joan Crawford is doubtless the best example of the flapper,” wrote F. Scott of the famous silent movie star. “The girl you see at smart night clubs, gowned to the apex of sophistication, toying iced glasses with a remote, faintly bitter expression, dancing deliciously, laughing a great deal, with wide, hurt eyes. Young things with a talent for living.”

We’re talking about an attitude here, more vibe than woman: an idea as much as a tangible girl. The flapper is an idealized vision concocted by the rising ad industry, makeup companies, Hollywood, and the popular press of the ‘20s. She’s the embodiment of the desire for freedom and fun that so many women feel in this age. Flapperdom was a lifestyle for people to fear, or to aspire to, but she was also very real. We’re going to talk a lot more about women’s work, home lives, rights, fashions, courtship – all the everyday life tidbits your hearts desire - in future episodes. But for now, let’s deconstruct the flapper and find out what it takes to be one.

The first thing to know about a flapper is that she likes to do the unexpected. “Of all the things flappers don’t like,” wrote one self-proclaimed flapper in a New York Times Magazine article, “it is the commonplace.” And she isn’t afraid to do things in public that most men have never seen a woman do before.

For one thing, she smokes cigarettes. Before the Great War, women weren’t supposed to put cigarettes to their “pure” mouths, and a gentleman wasn’t supposed to smoke in the presence of a lady without first asking her permission. But when they became a cheap commodity to send to the troops, many U.S. soldiers got addicted, despite the fact that people were already calling cigarettes the “devil’s toothpicks.” Henry Ford and Thomas Edison sent letters to their employees warning them about their harmful health effects, and they refused to employ smokers altogether. But we flappers don’t care about Henry Ford’s opinion on the matter, and we’ve taken up smoking as a form of social rebellion. All of our favorite movie stars smoke on screen: it’s considered a cool, glamorous habit. Tobacco advertisers like Lucky Strike intentionally target women, marketing cigarettes as an appetite suppressant: “Reach for a Lucky Instead of a Sweet.” Campaigns like this are, unfortunately, super successful, thus you shouldn’t be alarmed if you’re out for the evening and one of your friends asks you to “butt me.” (Butt me: hand me a cigarette).

A bad girl’s habit if ever there was one.

Citation: “Flappers Smoking,” The Smithsonian Magazine, accessed February 12, 2023.

For another, flappers go out driving in cars. It wasn’t that long ago that courtship was conducted mostly at home on front porches, under the constant and watchful eye of parents. But when the bicycle hit the scene in the 1890s, women and men had a new way to meet up and spend some time alone. Take Illinois couple Otto Follin and Laura Grant. “We rode till half past nine,” Otto wrote, “and then we sat down to rest by the lake and were alone and I knew that I could touch her if I wanted to and I did, just a little.…” The automobile takes this sort of travel to a whole new level. It’s both a mode of transport AND a cozy, private space for couples to hang out in. Flappers are hitting the open road with their beaus and making out in the backseats of cars with their cuddle cootie. Cuddle cootie: a young man who takes a girl for a ride in an automobile. “You can be so nice and all alone in a machine,” one flapper wrote. “Just a little one that you can go on crazy roads in and be miles away from anyone but each other.” And boy do they. In one year in Muncie, Indiana, some 30 girls were brought into the courthouse charged with “sex crimes” - and half of them were found in parked cars. Many parents hate the independence “the devil’s wagon” gives their charges. One father warned his daughter of the perils of “going out motoring for the evening with a young blade in a rakish car waiting at the curb.” To which she replied, “What on earth do you want me to do? Just sit around home all evening!”

Driving down Mischief Lane.

“Flapper Posing with her Car,” Vintage Everyday, accessed February 12, 2023.

Why should they? They have the vote, they have a job, they have their own money. There are things to do, people to see, fun to be had, and envy to inspire. Flappers have big carpe diem energy. As Zelda wrote, “The best flapper is reticent emotionally and courageous morally. You always know what she thinks, but she does all her feeling alone…she has a right to experiment with herself as a transient, poignant figure who will be dead tomorrow.” This fiercely independent and carefree attitude drove the flapper’s “bad girl” behavior, and earns her a nasty reputation among the old fogies (noun: old fashioned, conservative grumps) amongst us. But at least we’re having a lot of fun.

“If one judges by appearances, I suppose I am a flapper,” writes Ellen Welles Page in 1922. “I am within the age limit. I wear bobbed hair, the badge of flapperhood. (And, oh, what a comfort it is!), I powder my nose…I adore to dance. I spend a large amount of time in automobiles. I attend hops, and proms, and ball-games, and crew races, and other affairs at men’s colleges... Attainment of flapperhood is a big and serious undertaking!”

Flapper fashion was bold, beautiful, and columnar.

A 1920s fashion plate, accessed from the University of Vermont collection on February 21, 2023.

THE FLAPPER UNIFORM

But to truly be a proper flapper, a gal has got to dress the part. In the years before the Great War, the Gibson Girl was considered the bee's knees (Bee’s Knees: the best), the height of ideal feminine beauty. She cinched herself into a restrictive S-bend corset that emphasized a large bust, a tiny waist, and large hips. She wore simple high necked blouses with close fitting long sleeves and long flared skirts that skimmed the floor. Their faces were devoid of makeup, and they kept their long hair in pompadour updos.

By the 1910s, some daring ladies were already testing out styles that would later come to be associated with flappers, but it wasn’t until World War I broke out that women’s fashion started taking a drastic turn. Scores of women took on jobs formerly filled by men, many of which required uniforms. Thus women began wearing men’s clothes, and the military look crept into women’s fashion. Fabric shortages meant that skirts became shorter, and lighter materials like silk and jersey were favored, as heavier materials like wool were diverted to the troops. Simple looks were far more practical, and a simpler, some would say boyish silhouette started to become a la mode. By the time the fighting stopped, gender dictated dress codes had relaxed considerably, and clothing choices that had once been considered scandalous were more acceptable. The flapper has arrived, and damn is she stylish.

We’re going to go into way more detail on everything we’d wear on the day to day in the 20s in another episode, so I’m not going to take us through our outfit step by step, but I AM going to talk about the fashion statements that mark us out as flappers. Let’s bust a few myths about our attire.

Actually, let’s start with our bodies, and the idea that we need to be thin to rock these fabulous outfits. You’d think the magazines and style guides of the era would be encouraging us to diet, given the whole “boyish silhouette” so synonymous with the flapper. And while we do see SOME of that sort, and oft-muttered words like ‘slender’, ‘svelte’, and ‘sleek’ aren’t exactly encouraging to our modern ears, the 1920s ideal isn’t about being thin. It’s about being squat, compact, and curveless. For many, creating this look isn’t about changing our bodies. It’s about wearing things that shape them into the outline we desire.

Another myth we hear about flappers is that they didn’t wear a corset: never ever. Plenty of ladies are reaching for shapewear to get the tubelike silhouette we’re going for. But it’s a lot more lightweight than what our mothers are wearing, with very little boning, lots of elastic, and MUCH less structure. And there’s the even newer girdle: it’s like a corset, but it starts at the waist. With all that shimmying we’re about to be doing, I’d wager few of us are going out without a LITTLE bit of shapewear under there. That said, the flapper becomes rather infamous for going corsetless. Of the 1,300 working girls interviewed in Milwaukee in 1927, only 70 of them admitted to wearing a corset. After all, they’re not the easiest thing to work or work out in, they’re symbolic of Victorian-era oppression, AND it’s bad for her social life. “The men won't dance with you if you wear a corset,” a collective of flappers explained to The New York Times in 1920. It means he can’t cop a proper feel! More importantly, corsets are hard to dance and move freely in, and that just won’t do at all.

We are still wearing stockings, though. Although our mothers are probably still wearing traditional black, ours are skin-colored, thanks to the low price of a newly invented fabric called “rayon.” Skin colored stockings are hot because they give the appearance of bare legs (scandalous), and we want to draw as much attention to our gams (Gams: legs) as possible.

Our evening dress, too, is very different from what our mothers wore in their heyday. The typical flapper is going for the “la Garçonne” look (French for boy). “Women no longer exist,” one grumpy fashion critic wrote. “All that’s left are the boys created by Chanel.” In other words, the hourglass is out, ladies: we flappers are going for an androgynous, with dresses that deal mostly in long, straight lines and contain a lot less fabric than before. It’s likely to be some form of rectangular sheath, somewhat loose fitting, skimming rather than hugging your frame. It will have what’s called a dropped waistline that falls at the area around your hips. Flapper dresses are less restrictive, perfect for dancing, and made in moveable fabrics like artificial silk, cotton, or rayon. They’re fairly simple in construction, but they’re usually ornately decorated with bows, silk flowers, frills, or clever drapery to reflect the exuberance and decadence of the period.

These dresses are much less structured than the ones from before the war: so much simpler. But the thing that really shocks society is how much skin they show. As one disgruntled chap writes: “This year’s styles have gone quite a long step toward genuine nudity.” And while these styles don’t look all that racy to our eyes, they’re quite a shock to many in the era. Our evening dress will probably lack sleeves – something we haven’t seen women doing in most Western countries in public since, say, ancient Greece - and while it’s not going to bare even one ounce of cleavage, it’s going to show a shocking amount of leg. If we’re in the early 1920s, it’s longer than you’re probably thinking: skimming a few inches above our ankles. If it’s the latter half of the decade, though, they’re likely to hit just below our knees, though the truly brave flapper might hike it up a little higher. Before the 1920s, it was blasphemy to even show your ankle in public, so knee-length flapper dresses are seen by some as a sign of our wanton ways. One parent complains, “Girls aren’t so modest nowadays; they dress differently. We can’t keep our boys decent when girls dress that way.” The “she asked for it by dressing like a hussy” excuse: my favorite. Laws about skirt length are very common, because apparently lawmakers have nothing better to do. Twenty-one state legislatures discuss or pass bills regarding skirt length in the 20s, and in Utah, a woman could be thrown into prison for wearing a skirt three inches above her ankle. One newspaper commented, “It would seem that, were these to become laws, the dress with its four-inch-high skirt which would be moral in Virginia would be immodest in Utah, while both the Utah and Virginia skirts would be wicked enough in Ohio to make their wearers subject to fine or imprisonment.” With this much confusion, a girl might as well flash a little knee if it pleases her. Some of us are even giving them a makeover! Knee rouging is definitely a thing for flappers, to draw attention to what is seen as thoroughly erotic body part. By the later 1920s, this trend escalates to full-on knee painting. One 1925 poem read, "And, my, here comes a beauty; I watch as it walks by - a painting like that always seems to catch my eye. As one sees a comely miss with both knee-caps ablaze, studying art becomes a treat to all of us these days.”

In criticizing this new kind of woman, skirt length seems to be the easiest point of entry. It’s hard to overstate how scandalous many people find the flapper uniform. While some critics hate on flappers for their lack of modesty, others hate them for their lack of shame. One Hugh A. Studdert Kennedy had so much to say about women’s fashion that he wrote a whole essay called “Short Skirts,” in which he complains, “the lack of morality is not in the nakedness but in the shame, and the shame grows less day by day.” How dare women stop being ashamed of their bodies! Even some women hate flappers, for their *checks notes* lack of “taste. One Mrs. John B. Henderson, a huge proponent of dress reform and someone who really needs a hobby, claims that “society women” from all over the U.S. were coming together to “condemn such vulgar fashions of women’s apparel that do not tend to cultivate innate modesty, good taste, or morals.” It’s a woman’s moral obligation to look pleasing for men, and the flappers’ loose dresses and heavy makeup are unattractive. Mrs. Henderson was probably super fun at parties.

On to our hair. Let’s talk about the signature flapper haircut: the bob. In the 1910s, virtually every woman still had long hair, except for Irene Castle, a glamorous ballroom dancer well known for her fashion taste. Castle was one of the first women to rock the bobbed look way back in 1915, after cutting her hair for convenience before a surgery. She liked it so much that she kept it that way, and others began to copy her look: she is largely credited with popularizing the bob in the United States. Many flappers will walk into the salon and simply ask for the “Castle” bob. By the mid 1920s, film stars like Gloria Swanson, Clara Bow, and Louise Brooks also had them, as did famous cabaret dancer Josephine Baker and tastemaking designer Coco Chanel.

Of course, not everyone has a bob – there are lots of ways for those of us with long tresses to get the bob look without breaking out the scissors – but it becomes intrinsically linked to the bold, scandalous flapper. In a story by F. Scott Fitzgerald called “Bernice Bobs Her Hair,” published in the May 1920 issue of The Saturday Evening Post, he tells us how Bernice’s short locks cause a veritable scandal in her family, and how she is ostracized by her friends by it. Historically, long hair had always been symbolic of a woman’s femininity, so to chop it off in favor of a more masculine hairstyle is considered a serious transgression…which is exactly why many flappers did it. The look’s so shocking that many hairdressers flat out refuse to do it. So instead of heading to the hen coop (Hen coop: beauty parlor) to get our haircuts, we’re more likely to go to a barbershop.

In our mothers’ day, the only women who wore visible makeup were ladies of the evening and actresses. But any flapper worthy of the name is also wearing makeup. Especially at night, when the looks get MUCH bolder. The flapper’s makeup is a LOOK, heavily influenced by the big film stars of the day. The eyebrows are long, arched, and super thin, and we’ll be using an eye pencil or mascara to make them darker. The more hardcore amongst us will shave their eyebrows off only to draw them on again with two super thin lines. We’ll be reaching for a darker eyeshadow palette and using eyeliner quite liberally, thanks to the Egyptomania of the 1920s, and the revival of the classic Cleopatra. We will wear power, and take a pressed powder compact with us, or some loose powder in a metal tin. Flappers also like a flushed look, and what we now call blush is referred to as “rouge” in the 20s. Now, on to that other very distinctive flapper hallmark: our “cupid’s bow” lips. The look is created by Hollywood makeup artist Max Factor, and it’s the gold standard for flappers. The cupid’s bow is a heart-shaped lipstick look, designed to exaggerate the lips to make them smaller and more feminine. Heart-shaped lip stencils were sold to help draw the perfect cupid’s bow, and dark red is the lip color of choice for most flappers. Thanks to a retractable metal tube invented in 1915, lipstick is easy to apply on the go.

Cover illustration, Life magazine, February 18, 1926, showing a well dressed old man dancing with a flapper. Accessed from the Library of Congress on February 21, 2023.

OUT ON A TOOT

If there’s one thing a flapper loves, it’s going out in the evening. 1920s leisure culture gives men and women more chances to have fun together unchaperoned. Popular rides at amusement parks rated the intensity of a couple’s kisses, while roller coaster rides advertised their thrills with slogans like “Will she throw her arms around your neck and yell?” One of our favorite things is to go out dancing. Our mothers lament our trips to the cabaret, speaking of the wonderful, stately balls of their youths. But, as one high society flapper argues in The New Yorker, the debutante balls of the 1920s are restrictive, tedious, and filled with boring men:

“If our Elders want to know why we go to cabarets, let them go to the best of these, our present-day exclusive parties, and look at the stag lines. There they will see extremely unalluring specimens…There is the partner who is inspired by alcohol to do a wholly original Charleston, a dance that necessarily becomes a solo, as you can’t possibly join in, and can only hope for sufficient dexterity to prevent permanent injury to your feet. There are hundreds of specimens, each poisonous in his own individual way. And there are hundreds of pale-faced youths, exactly alike, who have forced the debutante to acquire a line of patter that will apply with equal appropriateness to all the numberless, colorless young men whom she once had the misfortune to meet, and with whom, if they so choose, she must continue to dance at every party. At last… tired of vainly trying to avoid unwelcome dances, tired of crowds, we go to a cabaret… We have privacy in a cabaret. We go with people whom we find attractive…We are with people whose conversation we find amusing… Yes, we go to cabarets, but we resent the criticism of our good taste in so doing. We go because, like our Elders, we are fastidious. We go because we prefer rubbing elbows in a cabaret to dancing at an exclusive party with all sorts and kinds of people.”

Gone are the chaste waltzes and two-steps of the before times: flappers love doing the Charleston and dancing spiritedly to jazz. Many old fogies believe that jazz, with its fast-paced and uninhibited beats, can be harmful to one’s health. They also believe the Charleston is sinful, and many places outright ban it. In Cleveland, a city ordinance also prohibited “flirting, spooning and rowdy conduct of any kind” in dance halls, and in Oshkosh, Wisconsin, couples were barred from “looking into each other’s eyes while dancing.” Nightclubs and cabarets are the lifeblood of the flapper. And of course, we love our speakeasies. Prohibition and flapperdom go hand in hand.

Alcohol consumption was one of the most strictly gendered activities in America. Before the war, saloons were a man’s domain, and often single men at that. At the turn of the century, it was illegal in some states for women to even enter one. Many sold women alcohol only to shoo them away and encourage them to drink at home. But when Prohibition made drinking illegal, it inadvertently changed things. The Volstead Act policed the manufacture, sale, and distribution of liquor, but it didn’t punish its purchase or consumption. Thus speakeasies abounded, and they were more than happy to accept female patrons. Many of the new cocktails they serve are favored by women, who prefer them to the straight beer and whiskey most saloons served. They introduce table service, powder rooms, and jazz bands to make the environment more appealing to women. Such spaces give them license to drink, dance, and—horrors!—swear.

Speaking of, let’s pause to practice a few flapper phrases, courtesy of the July 1922 edition of Flapper magazine. While out on the town, someone’s likely to call us a “biscuit” (a pettable flapper), and that’s a good thing. We’ll listen to some good whangdoodle (Jazz-band music), drink “foot juice” (cheap wine) or “jag juice” (hard liquor), and get a bit “zozzled” (drunk) with our “jelly beans” (boyfriends). Just make sure to watch out for wind suckers (people who boast too freely), mustard plasters (men who dance too close), and lallygaggers (young men addicted to attempts at hallway spooning).

The speakeasy is the flapper’s natural habitat, and drinking is another form of social rebellion. Good girls aren’t supposed to drink in public. Prohibition only seems to tip us into excess. After it’s made into law, the percentage of women arrested for public drunkenness soars. According to the infamous flapper Lois Long: “If you could make it to the ladies’ room before throwing up, you were thought to be good at holding liquor… It was customary to give $2 to the cab driver if you threw up in his cab.”

Lois was great at two things: writing and shocking people.

A posed parody shot in The New Yorker offices of writer Lois Long (right) and a scandalized 1890s woman.

Lois Long is a 20-something writer who embodies the flapper lifestyle better than anybody. Writing under the pseudonym Lipstick in her wildly popular column, “Tables for Two,” she spends her nights reviewing nightclubs for The New Yorker. Her humorous descriptions of her speakeasy exploits earn her fame and a large paycheck, putting her in the top 15% of 1920s female earners[3] . "I shall write about drinking,” she wrote in 1926. “Because it is high time that somebody approached this subject in a scientific, constructive way. The answer, my friends, lies with the Youth of America. It lies in the nursery and the schoolroom. From the brawling brats of today come the good eggs of tomorrow. We will teach the young to drink."

Besides all of this driving, drinking, dancing, and general merrymaking, the flapper is also having sex. She’s going to petting parties and necking in the backs of automobiles. “We do these things because we honestly enjoy the attendant physical sensations.…” one collegiate gal at Ohio State wrote. “The girl with sport in her blood … ‘gets by.’ She kisses the boys, she smokes with them, drinks with them, and why? Because the feeling of comradeship is running rampant.” Louise Brooks, one of the film stars that made the flapper life seem so glamorous on and off the screen, is incredibly open about her sex life. She would tell friends that she slept with an average of 10 men a year. Some estimates have it that some third of girls in the ‘20s lose their virginity before marriage, and that surveys from the time report that more and more men didn’t see virginity as something a gal needed to be ideal wife material. We’ll talk more about dating and sex in future episodes, but plenty of flappers are doing it, as well as using contraception. As Lois Long wrote, “You never knew what you were drinking or who you’d wake up with.”

That doesn’t mean that most flappers won’t eventually marry. Their views of liberated independence only extend so far. Even The Flapper magazine wasn’t willing to imagine a world in which a woman rebelled so much that she rejected marriage entirely. It published a poem describing the flapper:

She’s independent, full of grace, a pleasing form, a pretty face,

is often saucy, also pert, and doesn’t think it wrong to flirt;...

but she is true as true can be, her will’s unchained, her soul is free;

she charms the young, she jars the old, within her beats a heart of gold;

she furnishes the spice of life – and makes some boob a darn good wife!

CRITICISMS

So, how is society reacting to these young women with painted lips and exposed knees? In a word… not well. In his 1923 bestseller, Flaming Youth, Samuel Hopkins Adams writes that the flapper is, “restless and seductive, greedy, discontented, unrestrained, a little morbid, and more than a little selfish,” and one concerned university dean complains that flappers exalt, “personal liberties and individual rights to the point that they are beginning to spell lack of self-control and total irresponsibility in the matters of moral obligation to society.”

Flappers alarm many men, who watch in horror as they do all the activities that were previously only for them. In drinking, smoking, and flirting, they are rejecting the social status previously assigned to them. They needn’t worry. Flappers may be voting and sleeping around, but they still aren’t seen as men’s equals: not by a long shot. Their bodies are still subject to intense scrutiny and control, and their worth is still largely based on the degree to which they adhere to the standards of behavior and appearance that men create for them. Some seem fixated on the perceived relationship between the flapper’s fashion choices and the so-called unprecedented depravity of a whole generation of young women. After all, they’re supposed to be the ones concerned for the morality of society. Flappers are ruining the good name of women everywhere by *gasp* showing their knees.

But the flapper’s harshest critic is the staunch women’s rights activists. Many flappers are accused by that crowd of being apolitical, of reaping the benefits of women’s rights without furthering the cause. As Mary Herton Vorse complained, “the flappers are wasting their time flaunting their youthfulness, wearing make-up and dancing.” Flappers view suffragettes as old fashioned, dowdy, and lame, and the word “feminist” as uncool, while the activists pushing for the Equal Rights Amendment feel that flappers are undermining their cause by dressing for the male gaze. While some view flapper fashion as a liberated expression of open sexuality, others see it as submitting to a narrow ideal that positions them as a kind of possession. Even Zelda Fitzgerald recognizes this aspect of the lifestyle, writing, “I believe in the flapper as an artist in her particular field, the art of being—being young, being lovely, being an object.” Flappers are criticized by Zelda herself in the late 1920s, when she complained about those who jumped on the bandwagon without fully embracing the rebellious nature of flapperdom. “Flapperdom has become a game; it is no longer a philosophy… Three or four years ago, girls of her type were pioneers. They did what they wanted to, were unconventional, perhaps, just because they wanted to for self-expression. Now they do it because it’s the thing everyone does.”

Based on the number of critics decrying them, you’d think that every single woman in America is tucking a flask into her sleeveless dress. But of course, not every young woman in the 20s is a flapper. They aren’t as pervasive as popular culture has made them out to be. The hard-core Lois Longs and Zelda Fitzgeralds are the minority. Flappers are largely made up of young, single, upper and middle-class white women living in cities. Poor women, older women, and many women of color did not have the freedom or opportunity to embrace the flapper lifestyle. And many didn’t want to. That’s partly why the flapper causes so much uproar: she defies all of those still mostly conforming to established gender norms. And yet, these “good girls” aren’t the ones making front pages: flappers are. No one wants to read about what Mrs. Henderson cooked for dinner on Tuesday when they could pore over an account of Zelda Fitzgerald jumping into the Union Square fountain. Thus they leave a massive mark on the public imagination. Books, newspapers, magazines, films, songs, paintings, and advertisements all worship the flapper, both during the 20s and long after it.

These bright young things with a talent for living were loved, and they were hated, and some of the criticisms lobbed at them were certainly warranted. In their wild pursuit of pleasure and autonomy, they never paused to ask why their lifestyle was only available to white women with money, or actively try to leverage their power to advance women’s rights. But while the flapper may not be campaigning for equal rights like her elder feminists might like her to, she IS actively demanding her right to make her own choices. As historian Judith Mackrell wrote, “they weren’t the first generation in history to seek a life beyond marriage and motherhood; they were, however, the first significant group to claim it as a right.”

The flapper stood for liberation and autonomy, and the right to express herself. Above all, the thing that defined the flapper was her desire for choice. One magazine editor summed the mood up perfectly in his 1925 article, “Flapper Jane,” “Women have highly resolved that they are just as good as men, and intend to be treated so. They don’t mean to have any more unwanted children. They do not intend to be barred from any profession or occupation which they choose to enter… If they want to wear their heads shaven, as a symbol of defiance against the former fate which for three millennia forced them to dress their heavy locks according to male decrees, they will have their way. If they should elect to go naked nothing is more certain than that naked they will go, while from the sidelines to which he has been relegated mere man is vouchsafed permission only to pipe a feeble Hurrah! Hurrah!!”

Hurrah, then, for the flappers!