Lady Killers: The Women of Chicago’s Murderess Row

A woman walks down the echoing hall of a prison. Girls grip the bars, some looking resigned, others desperate. But she doesn’t stop until she gets to a particular cell. The woman inside it bats her wide, beautiful eyes, her auburn hair shining out against the prison’s dark walls. Bulbs flash as journalists take her picture. They all learn toward the woman like moths to a flame. But the new arrival hangs back, jaded and wary. It is clear to Maurine Watkins that this woman is guilty. So why are these men hanging on her every word? Maurine isn’t about to let this woman charm her. She is going to show the world what she is. But in reporting on her trial, Maurine will immortalize Beula Annan, and the accused murderesses in the cells around her. She will turn them into some of the 1920s biggest stars.

Settle in for a tale of passion, jealousy, corruption, and the lady killers who entranced 1920s America. Grab your gun, your best fur coat, and a flask of bootleg gin. Let’s go traveling.

beulah and belva have come to slay (quite literally).

Beulah (left) and Belva (right) dressed up for their day in court. “Beulah Annan and Belva Gaertner,” The Chicago Tribune, March 9, 2023, accessed September 29, 2023.

resources

Douglas Perry, The Girls of Murder City: Fame, Lust, and the Beautiful Killers Who Inspired Chicago, New York: Viking, 2010.

“Helen M. Cirese,” DePaul University, accessed September 29, 2023.

Rachel Goldsmith, “Murderess Row: Selling Morals to 1920s,” Schultz-Werth Award Papers, South Dakota State University, July 24, 2022, accessed September 29, 2023.

Beth Fantaskey Kaszuba, “‘Mob Sisters’: Women Reporting on Crime in Prohibition-Era Chicago,” Graduate Dissertation, Pennsylvania State University, December 2013, accessed September 29, 2023.

Rae Nudson, “In the 1920s, a Makeover Saved this Woman from the Death Penalty,” Racked, January 26, 2018, accessed September 29, 2023.

Ford, Anne. “The Real Roxie Hart Was Too Beautiful to Execute.” Chicago Magazine online, November 18, 2019, accessed September 29, 2023.

this mob sister is pulling no punches.

“Maurine Dallas Watkins,” from History Matters: Celebrating Women’s Plays of the Past, accessed September 29, 2023.

episode transcript

this may not match the audio exactly, as i often edit as i record. to that end, please ignore any typos (there are sure ot be a few of them).

WRITING CRIME

So here we are, in 1920s Chicago. Maurine Watkins has just arrived and is looking for a job. Maurine isn’t from here: she was raised in a quiet town by her minister father, and grew up loving her Bible study. She wanted to study Greek, the language of the New Testament. But she enjoyed writing, too. In a playwriting workshop, a professor told her that if she wanted to be a great at it, she needed to go and do some living. So she packed up and moved to the debauched, violent, exciting city of Chicago.

Maurine snags a job at the Tribune, the city’s biggest paper. The Tribune is big news; by the early 1920s, its daily circulation was over 500,000, and 800,000 on Sunday. It is also one of the only newspapers of note during the Prohibition era that gives women the same opportunities as men. While the Associated Press and New York managing editors are turning down female applicants, the Tribune is boasting about its female staff. The paper is keen to attract female readers, and the advertisers who want to sell them things. As one ad notes, “countless Mrs. Smiths . . . get a particular enjoyment” from news stories written by women, “as seen with a woman’s eyes and with a woman’s super-sensitiveness to truth.” Almost all women in newsrooms write for the society pages. “They give advice to the lovelorn,” said one New York Times reporter. “They edit household departments. Clubs, cooking, and clothes are recognized as subjects particularly fitting to their intelligence.” Others write stories of personal tragedy. These so-called “sob sisters” are sent to cover trials in ways meant to elicit emotion, rather than sticking strictly to the facts. Although they often covered violent crime – or, more precisely, its courtroom aftermath – the sob sisters’ work reinforces prevailing newsroom notions about women’s inability to write factually and without undue sentiment. “On the big story her vision is apt to be [too] close and her factual grasp inadequate…” one New York Herald Tribune reporter said. “They can’t depend on the variable feminine mechanism.”

But somebody has to cover the female crime phenomenon sweeping Chicago. Murder, it seems, is in the air. The number of killings committed by women has jumped 400% in just forty years, making up 10% of the total murder count. Husbands and lovers are turning up dead in droves. Male journalists resent having to cover girl bandits and murderesses, but female journalists are happy to step into the fray. These “mob sisters,” are the antithesis of “sob sisters.” They report on violence, corrupt government officials, and mobsters in ways that are cynical, witty, bemused, scornful, even jaded. But as exciting as the job can be, it’s also confronting. “I would rather see my daughter starve,” one editor said, “than that she should ever had heard or seen what the women on my staff have been compelled to hear and see.”

“I would rather see my daughter starve than that she should ever had heard or seen what the women on my staff have been compelled to hear and see.”

The Tribune’s first mob sister collapsed in the newsroom after interviewing a woman whose son attempted to kill her. A week spent in morals court listening to prostitution crimes made her sick. By the time she called it quits, she weighed just 98 pounds. Enter Maurine Watkins: small, unassuming, beautiful, respectable, pragmatic. Maurine did not bob her hair or display her knees. She also wasn’t easily shaken; she liked her new city’s dangerous edge. “Gunmen are just divine,” Maurine took to saying. “They have such lovely, quaint, old-fashioned ideas about women being on pedestals. My idea of something pleasant is to be surrounded by gunmen.” Their matter-of-fact attitude toward violence was awful, and she knew it, but there was something in Maurine that found them immensely thrilling. She was hungry to cover some of the city’s worst crimes. As she told readers, “Being a conscientious person, I never prayed for a murder, but hoped that if there was one, I’d be assigned to it.”

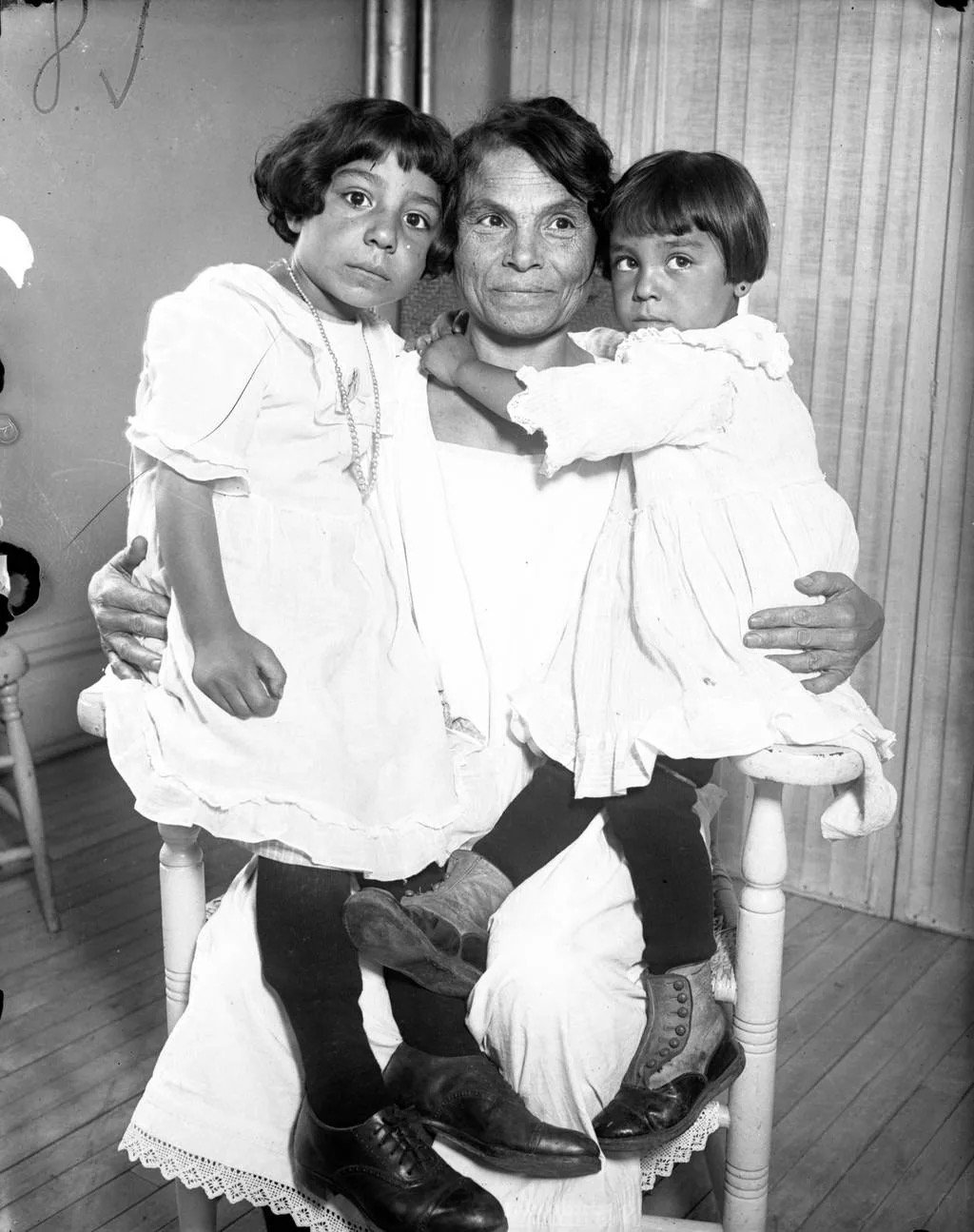

“Sabella Nitti with Belva Gaertner and Kitty Malm,” The Chicago Tribune, March 9, 2023, accessed September 29, 2023.

MURDER SHE WROTE

She’d been working at the Tribune for just over a month when a new and intriguing report came in. In the wee hours of March 12, 1924, two policemen were walking their beat in the streets of Chicago when they passed a woman getting out of an idling car. They didn’t think much of it until they heard a shot ring out through the darkness. When they ran back to the car, they found a bottle of gin, a used pistol, and a dead man.

An hour later, police knocked on the door of one Mrs. Belva Gaertner. The cabaret singer was in her robe, looking shaken. Nearby were her expensive fur coat, now blood-soaked, and a broken watch, which stopped at 1:15am. A man has been found dead, they said, and in your car, Mrs. Gaertner. What did she have to say about it? “I don’t know,” she replied. “I was drunk.”

Belva was still drunk when they set out for the police station. She told officers that she and Walter Law had been seeing each other for a couple of months. She said that around midnight, they were saying goodbye when a gunshot came from somewhere. She thought it might have been a stick-up man. She got scared, she said, and so she ran. But Belva did admit that she and Walter had been fighting. She’d danced with another man that night, you see. “I was frightened. Last Sunday night when he took me home he wouldn’t talk to me all the way home, just sneered and said, ‘I ever see you with anybody else I’ll wring your neck.”

Maurine listened to a tearful Belva working a crowd of policemen and reporters. “Did you shoot Law?” the Assistant State’s Attorney asked. “I don’t see how I could,” Belva replied. “I thought so much of him.” At last, one of the journalists recognizes her: isn’t she Belle Gaertner, the popular cabaret dancer whose violent divorce caused such a stir? Back in 1911, she married William Gaertner, a wealthy and respected businessman. But her drinking, cheating, and general wildness soon had William wondering if he’d made a mistake. Things got so bad he called the cops, saying he would file for divorce, citing cruelty. Things got so dramatic that they ended up in the papers. And here the woman is again, accused of murder. But when Freda Law, William’s wife, shows up, she refuses to believe it. “I do not believe she killed him. The bullet that caused his death came from the outside, and probably never was meant for him. Walter was devoted to me. I never suspected him of doing anything that might give me cause to be jealous, and I don’t suspect him now.”

The morning after the arrest, sober and rested, Belva starts pushing herself out of the frame more forcefully. “I tell you I can’t recall what happened,” she repeated for reporters and police. “Somebody must have shot him, but I can’t remember how it was done.” There is something about her: a gravitas, a charm, that makes her an entrancing subject. It helps that she smokes and powders her nose for her admirers. She even drops quippy, perfect pull quotes like, “I think I can get my coat cleaned so it will look all right again.”

Belva, looking forlorn (and rather stylish) in her prison stripes.

Citation: “Cabaret singer and divorcée, Belva Gaertner spends time in Cook County Jail awaiting trial for the murder of Walter Law, 29, on March 12, 1924. (Chicago Herald and Examiner).” from The Chicago Tribune, March 9, 2023, accessed September 29, 2023.

At Belva’s inquest, police testimony built a damning picture. The manager of the Gingham Inn testifies that Walter and Belva had been there together, drinking. The coroner testifies that Walter had gotten a bullet through his right cheek, which exited through the left ear. One shot had been fired from the pistol left in the vehicle. It looks like murder, pure and simple. And Belva is sitting pretty in the frame. A co-worker of Walter’s goes on to say that, “Walter told me Monday that he planned to take out more life insurance because Mrs. Gaertner threatened to kill him. In a joking way he said he was afraid Mrs. Gaertner might shoot him. Three weeks before, he told me she locked him in her flat with her and threatened to stab him with a knife unless he stayed there.”

The coroner’s jury pronounces Belva guilty of murder. Her case will be moving to grand jury and trial. After the inquest, Belva and Freda answer questions just a few feet from one another. Freda says: “At first, I felt rather sorry for that other woman because she was guilty of killing and everything. But did you see her come in? She was almost giggling. Oh, I never knew I could hate anyone so much.”

Belva is moved to Cook County jail to await trial. William Gaertner, apparently a sucker for punishment, hired the best defence attorney in Chicago and brings her stylish clothes to wear. But Maurine isn’t impressed; this deeply cynical mob sister writes stories with a tongue in cheek tone and oozing sarcasm, which aim to reveal her murderess subject in the worst possible light.

“The latest alleged lady murderess of Cook County, in whose car young Law was found shot to death as a finale to three months of wild gin parties with Belva while his wife sat at home unsuspecting, isn’t a bit worried over the case. ‘Why it’s silly to say I murdered Walter,’ she said during a lengthy discourse on love, gin, guns, sweeties, wives, and husbands. ‘I liked him and he loved me– but no woman can love a man enough to kill him. They aren’t worth it, because there are always plenty more. Walter was just a kid– 29 and I’m 38. Why should I have worried whether he loved me or whether he left me?’”

Maurine details what she thinks will condemn the woman in the public’s mind: her laughter, her frivolity, her utter lack of concern as Mrs. Law planned her husband’s funeral. She printed every one of her outrageous quips. “Now that coroner’s jury that held me for murder. That was bum. They were narrow minded old birds– but they never heard a jazz band in their lives. Now, if I’m tried, I want worldly men, broad-minded men, men who know what it is to get out a bit. Why, no one like that would convict me.”

Belva’s story is big news: everyone wants to hear all about this accused murderess. But soon another, more glamorous woman will join Belva on what’s called “Murderess Row.” And she is going to steal the spotlight.

ENTER BEULAh of the soulful eyes

Beulah Annan was from Louisville, Kentucky. Married in her teens, with a son on her hip, she soon chased against the constraints of the domestic life. She started having affairs, and her husband wasn’t pleased about it. “You have never showed that you are capable of resisting temptation,” he wrote, and told her to leave town for the sake of their child. Soon Beulah married again and moved with her man to Chicago. “She was all that I thought a woman could be…” her second husband said. “I gave her every cent I made.” Beulah worked at Tennant’s Laundry, mostly because she got bored at home, with Al out working so much. He never wanted to take her out dancing. But she wasn’t afraid to find someone else who would.

Who could condemn those wide, innocent eyes?

Beulah Annan posing for a cameraman after admitting she killed her lover, Harry Kalstedt. Image from the Chicago Herald and Examiner. “Chicago's Murderess Row in 1924 — and all that jazz,” published Mar 09, 2023, accessed Dec. 2, 2023.

At 5pm on April 3, 1924, Beulah called her husband at work in a panic. “Come home, I’ve shot a man. He’s been trying to make love to me.” When Al got home, he found his wife drunk, a jazz record playing, and a bloody body of a man on the floor. When the police came, he tried to tell them he did it, but Beulah confessed.“I told him I would shoot. He kept coming toward me anyway, so there was nothing else for me to do but shoot him.” “In the back?” the officer asked, clearly dubious about her story. Beulah chose that moment to faint.

They took her to the station, where they continued to press her over the incident. No one believed it was self-defence. But everyone was intrigued by this beautiful girl with blue eyes and auburn curls, wearing a deliciously low-cut nightdress. How could such a delicate, pretty thing kill a man? Eventually, they took her back to the apartment to change clothes, hoping the sight of the blood on her carpet would shake the truth from her. Why were there wine bottles and empty glasses if you didn’t invite the man in? they asked her. Why was he shot in the back if he rushed at you? It’s clear the man was dead for hours before you called us: why is it that you waited so long? “You are right,” she said at last. “I haven’t been telling the truth. I’d been fooling around with Harry for two months.”

It turns out that Harry Kalstedt was her co-worker, and her lover. She told police he’d come by her place around lunchtime, and they’d gotten drunk together as they listened to her favorite record, “Hula Lou.” But soon they started fighting. She accused Harry of lying about having money to spend, and of seeing other women. She told him she was seeing another man too, hoping to spur on a jealous rage. It worked – things heated up. There was a moment when she and Harry both looked toward the bedroom, where Al’s gun was stored.

“Then you say he jumped up?” the police pressed.

Beulah: “I was ahead of him. I grabbed for the gun.”

Police: “And what did he grab for?”

Beulah: “For what was left–nothing.”

Police: “Did he get his coat and hat?”

Beulah: “No, he didn’t get that far.”

Police: “Why didn’t he get that far?”

Beulah: “Darned good reason.”

Police: “What was it?”

Beulah: “I shot him.”

Beulah Annan looking cute as she answers policemen’s questions. Image from the Chicago Herald and Examiner. “Chicago's Murderess Row in 1924 — and all that jazz,” published Mar 09, 2023, accessed Dec. 2, 2023.

This so-called Midnight Confession is soon all anyone can talk about. And Beulah keeps talking from her cell, saying things like, “I didn’t love Harry so much-but he brought me wine and made a fuss over me and thought I was pretty. I don’t think I ever loved anybody very much. You know how it is- you keep looking and looking all the time for someone you can really love.” Her husband Al was only steps away when she said this. He told reporters, “I’ve been a sucker, that’s all! Simply a meal ticket! I guess I was too slow for her… I don’t get any kick out of cabarets, dancing, and rotten liquor. I like quiet home life. Beulah wanted excitement all the time.” Still, he tried to come up with the money for lawyers to defend his her. “I haven’t much money, but I’ll spend my last dime in helping Beulah. I’ll stick to the finish.”

At the inquest, a new, more scandalous picture emerges. We find out that Beulah called Tennant’s Laundry at 4:10 that day, asking for Harry, even though he was clearly already dead in her flat. When the coroner arrived at 6:20, Harry had only been dead for about 30 minutes. She had hours in which she could have called for help, and didn’t. Instead, she danced along to Hula Lou as Harry lay dying. “She danced to the tune of jazz records a passionate death dance with the body of the man she had shot and killed,” one paper wrote. Maurine wrote, “Hula Lou was the death song of Harry Kolstedt, 29 years old, of 808 East 49th street, whom Mrs. Annan shot because he had terminated their little wine party by announcing that he was through with her.”

It’s decided that Beulah’s case will go to trial. When she arrives at Murderess Row, the seriousness of her predicament seems to finally hit home. But the woman in the cell next door doesn’t understand what she’s so worried over. “You pretty-pretty,” Sabella Nitti tells her. “You speak English. They won’t kill you– why you cry?”

NICE FACE, SWELL CLOTHES, SHOOT MAN, GO HOME

Beulah and Belva aren’t the only women on Murderess Row: far from it. Almost a year before they arrive there, Sabella Nitti was sentenced to hang for supposedly killing her husband. That’s when this 40-something Italian immigrant reported her husband, Frank Nitti, missing, along with their family’s $300 in savings. With so many children to tend, she couldn’t wait for him to return to her. Sabella married again, a man named Peter Crudelle. Two months after that, police found a badly decomposing body in a sewer catch basin. It was identified as Frank Nitti. Sabella and her 15-year-old son, Charlie, were brought in for questioning. Under heavy interrogation, Charlie finally cracked: Peter Crudelle murdered his father on Sabella’s order, and then he and Crudelle disposed of the body together. Speaking almost no English, Sabella understood none of what her son told policemen. She just nodded along, trusting it was the truth.

The trial and its coverage was hugely unfair to Sabella. Her lawyer, Eugene Moran, was so grossly incompetent that the judge warned him several times that he was harming his client. He would later be declared mentally ill. Even if he’d been fit, he didn’t speak Sabella’s language: he had no way of communicating with her about anything. Imagine sitting through your trial, unable to follow any of the proceedings, watching as a bunch of men decide your fate. The press was merciless and cruel, calling her greasy, dirty, even animalistic. “A horrible looking creature she was,” one wrote, “with skin like elephant hide, nails split to the quick, and the dirt ingrained deep in the cracks of her hands.” The coverage of her trial shocked her fellow inmates, who wrote to the papers to say that she was, “one of the cleanest women in the department, in her cell and her personal appearance.” But their words fell on deaf ears. On May 25, 1923, the state indicted Sabella, Peter, and Charlie for murder.

102 “husband killers” were tried in Cook County between 1875 and 1920. 16 were convicted; none had gotten the death penalty. And after seeing some 29-girl gunner acquittals in a row, the state’s lawmen were starting to get itchy. They were embarrassed that 90% of women tried for murder were walking free in their state. Why not make an example of Sabella, an immigrant who cannot speak for herself?

Sabella’s death sentence made her a national celebrity. The LA Times wrote, “For the first time in the history of Illinois, a woman has been given the death penalty for murder.” No one wrote the kinds of things about her that they would go on to say about Beula and Belva. She was no glamorous, tragic, seductive beauty. She was an immigrant, older, and poor. One of the Tribune’s articles about her sums up the frankly horrifying, zenophobic attitude of the time: “Twelve jurors branded Mrs. Sabelle Nitti ‘husband killer’ and established a precedent for the state of Illinois at 3 o’clock yesterday afternoon by giving the death penalty to the dumb, crouching, animal-like Italian peasant…a cruel, dirty, repulsive woman.”

Thankfully Helen Cirese was on the case. She and five other young Italian lawyers decided to take on Sabella Nitti’s appeal pro bono. Born to Italian immigrants herself, Helen became the youngest woman to pass the Illinois Bar exam, 10 months before her 21st birthday. But no one would hire her. “Women make good law students…” one male attorney said. “They can pass the examinations, including the Bar examinations, with honors and flying colors. But conditions are such that they do not seem to me equipped for the actual knock-down and drag-out fight required in the actual trial of lawsuits.” Helen begged to differ, and she was sure of Sabella’s innocence. She appealed her case, and the court agreed to hear a motion to set aside the verdict. Sabella’s defence team planned to argue that Sabella’s attorney had been incompetent, that Sabella could not understand him, that the evidence was suspect, that Charlie’s testimony was coerced, and that the motive was shoddy. Her conviction was clearly about ethnic and class biases, not justice. And when Belva and Beulah swanned into their jail, clearly guilty, but also glamorous, they highlighted an uncomfortable truth: pretty women could get away with anything, including murder. As Sabella herself: “Nice face–swell clothes–shoot man–go home.”

“Belva Gaertner, 38, center, listens during the coroner's inquest for the death of Walter Law, 29, held at the South Wabash Avenue station on March 12, 1924, in Chicago. (Chicago Herald and Examiner).” Accessed September 29, 2023.

Another of the less fortunate inmates on Murderess’ Row was 19-year-old Kitty Malm. In the weeks before Belva and Beulah were arrested, she was sentenced to life in prison for her crime. As a teen, she quit school to become a factory girl. At some point, she married a man named Max and had a daughter with him. But both married life AND her meager paycheck didn’t work out for her. In November 1923, she and her boyfriend Otto tried to rob a factory and ended up killing a security guard. Otto confessed: after all, he had a rap sheet as long as his arm. Otto said he was the one who killed the guard and accidentally shot Kitty. To show her devotion, Kitty tried to commit suicide in her cell. “You can now tell them that I done the shooting so they will let you go to take care of baby forever,” she wrote to him in her final note. “But please quit the racket and raise Tootsie in an honest way for your departing mama’s sake.” Days later, Otto changed his story. Now Kitty had shot the guard. She was confident, at first, that she wouldn’t be hung for it. All male juries were averse to punishing women. “Hang me?” she told reporters. “That’s a joke. Say, nobody in the world would hang a girl for being in an alley with a guy who pulls a gun and shoots.”

Kitty Malm’s best mug shot.

Citation: “Katherine "Kitty Malm" Baluk after turning herself in to police and confessing her involvement in the death of Edward Lehmann, circa 1923. (Chicago Herald and Examiner).” Accessed September 20, 2023.

But Kitty wasn’t like the white lady gunmen who had been acquitted before her. They’d been society ladies, and all pretty. Kitty was poor and uneducated. She’d stare right into a man’s eyes, her language was vulgar; the reporters didn’t like her at all. So when an ex-friend of hers outright lied, claiming Kitty kept two guns strapped to her hips at all times, the papers were all over it. They wrote that Kitty “carried a gun where most girls hide their love letters.” It caused a sensation, and let the state frame Kitty as a “hard” woman. Reporters called her the “dangerous Wolf Woman” and the “ferocious Tiger Girl.” In February 1924, the jury found her guilty of murder. To add insult to injury, Kitty received a divorce summons from her legal husband. He even claimed their 2-year-old daughter, Tootsie, wasn’t his. Kitty and Belva bonded over men while playing cards in prison. “Men are quitters,” Kitty told Belva. “They’re long on talk, but Lord, when it comes to the showdown, they’re yellow.”

Citation: Katherine "Kitty Malm" Baluk took the stand in her own defense during the murder trial, saying she had never carried a gun. Judge Steffens is on the bench. (Chicago Tribune historical photo).” Accessed September 29, 2023.

Belva and Beula are starting to get a little nervous about their court cases. Sabella’s conviction may have broken the streak of acquittals against lady killers, but Kitty’s drove home the fact that men were no longer scared of convicting them. And that wasn’t all. On May 7, a jury convicted Elizabeth Unkafer of killing her lover and sentenced her to life in prison. Before that, Mary Wezenak was convicted of manslaughter for serving poisonous whiskey. It was worrying, certainly, but one thing was clear to them: beauty, glamor, a good lawyer, and the press core were the keys to getting free.

“ Men are quitters. They’re long on talk, but Lord, when it comes to the showdown, they’re yellow!”

Beulah’s defence team decided they would present her as a virtuous working girl caught up in a rage and lean hard on the fact that Harry had a criminal record: turns out he had spent 5 years in a Minnesota prison for assaulting a woman. Way to pick a winner, Beulah! Her story changed, too, as did her attitude toward her cuckolded husband. It “must have been a blow for him to discover what had been going on behind his back,” she said, her large eyes filled with tears. She told them what they wanted to hear: that she was ashamed. “I suppose it is true that a man may drift into any woman’s life at some time and overpower one with his personality. Before you know it, without any intention to misstep, you find yourself completely engulfed. That was the way it was with Harry… That’s largely the trouble that brings most of the women in here. They fall in love with the wrong man.”

Many papers made Beulah’s story into an epic tragedy, a heartrending modern love story. Beulah had been lured into the world of jazz and booze and had broken her marriage vows. She was fallen, but she could still be saved. Her story was bigger than Belva’s or Kitty’s or Sabella’s. Newspapers sold out on Friday and Saturday when her face was on the front page. She posed for photographers in her jail cell, received food and roses from anonymous admirers, and got love letters from men across the country. And then, a day after Unkafer’s conviction, Beulah gathered the press and told them she was pregnant. Harry had attacked her after she told him she was carrying her husband’s child. The press loved the twist. Maurine alone was suspicious about this sudden revelation. “Will a jury give death–will a jury send to prison– a mother-to-be?”

“Will a jury give death–will a jury send to prison– a mother-to-be?”

Belva knew she couldn’t compete with Beulah’s beauty, so she schemed to get their pictures taken together as often as possible. She uses her husband’s money to become the Row’s most stylish occupant, and even opens a contraband cosmetics racket. “A jury isn’t blind, and a pretty woman’s never been convicted in Cook County,” one of the inmates told Maurine. The inmates cut each other’s hair and gave each other manicures. Friends and lawyers brought in outfits, and they conducted fashion shows. “When the girl in cell No. 4 was informed that her trial would be the following Tuesday, Belva gave her some really good ideas on costuming, coiffure and general chic. It helped the girl in No. 4 and it whiled away otherwise lonely hours for Belva, with the clothes sense.” Getting free was a beauty contest as much as it was anything else.

Lawyer Helen Cirese knew it too. She set about giving her client, Sabella, a complete and total makeover. “We simply reconditioned her,” she said later. “I got a hairdresser to fix her up every day. We bought her a blue suit and a flesh-colored blouse. We taught her to speak English, and when she walked into that courtroom she was beautiful–beautiful and innocent. I’ll never forget how she looked. You wouldn’t have known her.” In April 1924, Helen got Sabella’s verdict reversed. In June she was released on bail, and returned home to await retrial. But it never happened. In December, the state dropped the charges against her. Her cellmates watched with rapt attention and a building sense of hope.

HE SAID, SHE SAID

Beulah’s trial took place in late May. She was first called to the stand without the jury, to determine if the Midnight Confessions were even legal. Her lawyers argued they were worthless, since she had been drunk. The judge agreed. Beulah, meanwhile, looked as fetching as ever. “The courtroom was full of appreciative smiles directed toward the lovely girl beside the prisoner’s table…” a reporter said. “The pretty bob-haired maid assuredly was the fairest thing that had ever graced a murder trial in Chicago.” Others wrote of her tailored suit, black stain slippers, and lace collar. “With her flaming red hair showing at its best with a fresh trim and marcel, she made a picture which would rival paintings of the famous Titian.”

When Beulah took the stand on the second day of the trial, crowds had gathered. The nation was obsessed with the case. Movie cameras were rolled into the back of the courtroom, for theatrical newsreels, and fans rushed to make it inside.

Beulah, once again, told her version of the story. They drank, they danced, and then she told him she was pregnant. “But he refused to believe me– and boasted that another woman had fooled him that way, and that he had done time in the penitentiary for her. I said you’ll go back to the penitentiary if you don’t leave me alone. He said you’ll never send me back there. And I said, I’ll call my husband! And he’ll shoot us both! There’s a gun in there. And I pointed to the bedroom. ‘Where’s the gun,’ he asked, ‘let’s see it.’ Then we both started for the gun. He reached it first she said but I wrenched it out of his hand. Then he came for me, brandishing his arms. I seized him by the shoulder and spun him around. Then I shot.

That state tried to trip Beulah up in cross examination.

Lawyer: “Had Kalstedt ever been to your home before this day?”

Beulah: “No.”

Lawyer: “Had you been to any parties with him, or to any places of amusement?”

Beulah: “No sir.”

Lawyer: “How many drinks did you have Mrs. Annan?”

Beulah: “Three or four.”

Lawyer: “Had you been in the bedroom with him?”

Beulah: “No.”

Lawyer: “Was the gun in plain sight on the bed?”

Beulah: “Yes.”

Lawyer: “What time was it when you shot Harry Kalstedt?”

Beulah: “About 2:30 or 3:00 I think.”

Lawyer: “What time was it when you called your husband?”

Beulah: “I don’t know.”

Make it stand out

Beulah Annan with her third husband, looking cheekily, and prettily, innocent. She was acquitted earlier of killing her lover. Credit: from “The Real Roxie Hart Was Too Beautiful to Execute, And other tidbits from a new book on the real-life women who inspired Chicago” by Anne Ford. Chicago Tribune Historical. Accessed Dec. 2, 2023.

“The witness made a favorable impression, controlling her emotions, except during the dramatic crises of her recital,” The Evening Post wrote. Beulah was a married woman who shot her boyfriend. And yet, somehow, she appeared as a timid girl and a victim – one who claimed the moral high ground. But the State did its best to shatter that image. “a woman who didn’t want him there would have run out of the apartment and yelled for help,” they said in their closing arguments. “You have seen that face, gentlemen. The defendant is not the kind of woman men would tell to go to hell. She probably had never heard that before and it angered her…The verdict is in your hands, and you must decide whether you will permit a woman to commit a crime and let her go just because she is good looking. You must decide whether you want to let another pretty woman go out and say, ‘I got away with it!’” Her defense’s closing arguments reiterated that her confessions had been bullied out of her by the police when she was drunk. They painted a picture of a loving virtuous wife that had been slandered by the state and a drunken brute. Beulah began to sob prettily.

The jury came back with a verdict after only 2 hours: Not Guilty. Beulah went on pose for a photo with them. Maurine couldn’t believe it. “Men on a jury generously make allowance for a woman’s weakness, both physical and moral; she is unduly influenced, led astray by some man, really not responsible– poor little woman!” Beula, however, was free, and happy to play the lady who had learned her lesson. “ ‘I’m going to be a devoted wife from now on,’ she declared. ‘The most intense longing which I have is that I prove myself to be a good mother and a true wife. I want to show the whole world what kind of woman I really am.’”

An article on Bella’s tragic end. “Maurine Dallas Watkins: Sob Sisters, Pretty Demons, and All That Jazz,” from The Indiana History Blog, accessed Dec. 2, 2023.

Just a few days later, she announced that she was leaving her husband. “He doesn’t want me to have a good time. He never wants to go out anywhere and he doesn’t know how to dance… I want lights, music and good times. I love to dance. I love good food–and I’m going to have them.” It rather tarnished who image with the papers, but it was Al who had the hardest time, alone and saddled with Beulah’s legal bills. “I cannot make myself realize that Beulah has given me up,” he told reporters. “When we married we took solemn vows that it was for better or for worse, and that it was to exist until death parted us…Beulah is no different than any other woman. She is naturally weak and needs protection. She will come back to me.” She didn’t, but don’t feel too bad for him. 10 years after Beulah’s acquittal, Al was convicted of manslaughter for beating a woman to death during a drunken argument in their shared apartment. He didn’t call the police until 3 hours later.

“He doesn’t want me to have a good time. He never wants to go out anywhere and he doesn’t know how to dance… I want lights, music and good times. I love to dance. I love good food–and I’m going to have them.”

In June of 1924, it was Belva’s turn. She made sure to look gorgeous. Shops sent her dresses to consider wearing to the courtroom, knowing the papers would describe them in detail. “Class– that was Belva,” Maurine wrote later. “For she lived up to her reputation as ‘the most stylish’ of murderess’ row: a blue twill suit bound with black braid, and white lacy frill down the front; patent leather slippers with shimmering French heels, chiffon gun metal hose. And a hat–ah, that hat! Helmet shaped, with a silver buckle and cockade of ribbon, with one streamer tied jauntily– coquettishly–bewitchingly– under her chin.”

Belva’s lawyer didn’t try to make an argument. He simply poked holes in the state’s, which worked. Maurine was irritated by Belva’s calm throughout the proceedings. She wrote, “Her sultry eyes never lost their dreaminess as policemen described the dead body slumped over the wheel of her Nash sedan– the matted hair around the wound, the blood that dripped in pools– and her revolver and “fifth” of gin lying on the floor. Her sensuous mouth kept its soft curves as they told of finding her in her apartment– 4809 Forrestville avenue– with blood on coat, blood on her dress of green velvet and silver cloth, and blood on the silver slippers.” Maurine worried that she hadn’t been hard enough on Beulah in her coverage. She worried she had underestimated the woman, and thus helped her walk free. So when it came to covering Belva’s trial, she pulled no punches. And yet the trial moved quickly, over just two days. This time the jury took 7 hours to deliberate. When they pronounced the verdict, “Not Guilty,” Belva “laughed and cried in one breath.”

Maurine couldn’t believe another murderess was walking free. “Belva Gaertner, another of those women who messed things up by adding a gun to her fondness for gin and men, was acquitted last night at 12:10 o’clock of the murder of Walter Law. ‘So drunk she didn’t remember’ whether she shot the man found dead in her sedan at Forrestville avenue and 50th street March 12– But after six and one half hours and eight ballots the jury said she didn’t.”

Belva remarried William in May 1925, but they weren’t going to get their happily ever after. She got drunk every night and embarked on more affairs. When William confronted her, she hit him over the head with a mirror. In 1926, when William discovered a strange man in his bedroom, Belva screamed that she would kill him. He escaped and, once again, filed for divorce. Belva claimed William had “an extreme and abnormal sex passion,” but the press could not be swayed this time. One paper called William, “the most patient soul” since Job. After the divorce, she moved away to California. And yet, when William died decades, he still left most of his estate to Belva. Oh, William.

What about Kitty Malm, you wonder? She didn’t get free, like the others. She served the rest of her short life in prison. She was cheerful and helpful and worked as a clerk in the prison’s main office. And yet when Kitty tried for early release in 1930 and 1931 and failed both times. She fell ill with pneumonia in 1932, and died in late December. She was just 28 years old. Why did Belva and Beula get off, and Kitty didn’t? One reporter sums it up for us: “Her mistake was in being ‘hard boiled’ and none too good looking.” A sad indictment of the times.

ALL THAT JAZZ

Eventually, Maurine grew tired of police reporting. She turned to film criticism and light features instead. Eventually, she went back to her theater professor and her playwriting workshop. She already had an ambitious comedy mapped out, inspired by her time in crime reporting. She titled her play The Brave Little Woman. By the time she finished writing, it was simply called Chicago.

Maurine wanted her work to explore the criminal justice system, the problems with sensational journalism, and the stupidity of letting pretty, well-dressed murderers walk free. Maurine told the New York World that she “was portraying conditions as I actually found [them] during my newspaper work. For while the play may sound like burlesque or travesty in New York, it would pass for realism in its hometown.”

This is a time when plays are being fined for their morality, or lack thereof. Police raid productions for “corrupting the youth” and drag whole casts off to the clink. So when Chicago opens in the Music Box Theatre on December 30, 1926, it ruffles more than a few feathers. One reporter calls it “a shocker unfit for human consumption.” John Archer of the Yale Divinity School agrees, saying it is “entirely too vile for public performance.” And yet Chicago is a smash hit with audiences in New York, and is chosen as one of the best plays of the year. Soon enough, it opens in its namesake town. Belva Gaertner AND her lawyer show up for the premiere, obviously. And instead of being embarrassed at seeing her dirty laundry turned into theatre, Belva has this to say about it: “Gee, this play’s got our number, ain’t it.”

The silent movie version opens two days before Christmas in 1927. Years later, in 1942, Chicago will be remade as a talkie starring Ginger Rogers as Roxie, though the Hays Code means that it has to be cleaned up. Horrified, Maurine quits screenwriting and moves to Florida. She stops writing and spent the rest of her life rejecting entreaties to turn Chicagointo a musical. But when she dies in 1969, her family sells the rights, which is how we end up with a musical version of the drama by choreographer Bob Fosse. At least the man stayed true to Maurine’s cynicism, which I think she would appreciate. The musical will run for 936 performances, then return 20 years later to take the Tony for best revival of a musical. In 2002, Chicago the musical will hit theaters and win the Academy Award for Best Picture.

Beautiful, deadly, treacherous: for a while, the women of Murderess’s Row enthralled America. They enchant us still, with their tales of passion, violence, and of getting away with murder. Until next time.