Armed and Dangerous: Amazons and the Real Warrior Women Who Intimidated Ancient Greece

You’re battling your way through a sea of grasses.

You are a good fighter, trained from a young age, but the barbarian riding fast toward you is better. He is on horseback, riding without saddle or stirrup, clad in the clothes of his tribe: pants, long sleeves, and a pointed cap. No: it’s not a he. You see that now, but the sight is so strange to you that it takes a moment to understand: the warrior heading toward you is a woman. She and her horse are both decked out in gold, moving together as one fearsome creature. You watch her twist around and shoot a man behind her clean through with her bow and arrow, swift and brutal. It doesn’t even slow her down. Terror fills you, because she’s turning now, and her eyes have locked on you.

Even in your fear, you can’t help but marvel at her. Strong, wild, and merciless, so different from the good Greek women you grew up with. More than willing to bring her blade down. And just before she does, you gasp, waking up in your bed back in Athens. It isn’t the first time you’ve dreamt of the Amazons. It isn’t likely to be the last.

The ancient Greeks told lots of stories about the Amazons: the mythic bands of warrior women that Hellanikos of Lesbos described as “a host of golden-shielded, silver-axed, man-loving, boy-killing females.” They made up fantastic stories about both loving and subduing these women who were bold, violent, promiscuous, and independent: everything a good Greek wife wasn’t supposed to be. To many they were a fantasy, equal parts exciting and terrifying. And for a long time, scholars thought that was all they were: a figment of the Greek imagination.

But now we understand that the ancient world saw its fair share of warrior women, living on the move, hunting and fighting, living and dying on their own terms. It turns out the Amazons were real. Who were these women the Greeks saw in their pleasant dreams and worst nightmares? Let’s go hunting, beyond the myths and legends, and try to join them.

Grab a bow and arrow, some gold bangles, and your best leather chaps. Let’s go traveling.

Battle ready.

Marble statue of a wounded Amazon, courtesy of the MET.

My resources

books

Women Warriors: An Unexpected History by Pamela Toler, Beacon Press, Feb. 2019.

The Amazons: Lives and Legends of Warrior Women by Adriene Mayor, Princeton University Press, Sept. 2014.

Amazons: The Real Warrior Women of the Ancient World by John Man. Pegasus Books, Feb. 2018.

podcasts

Ancient History Fangirl’s three-part episode on Amazon women and the real-life warriors behind them. Find it wherever you listen to podcasts!

online

“How Horses Got Their Hooves.” By Steph Yin, The New York Times, Aug. 2017.

“The Real Amazons.” By Joshua Rothman, The New Yorker, Oct. 2014.

“Fu Hao, China’s first female general.” by Geni Raitisoja, GB Times, Oct. 2016.

and then stabbing ensued.

A pitcher (oinochoe) featuring a battle between the Greeks and some Amazons. Courtesy of the Museum of Fine Arts Boston.

THE AMAZON MYTH

Before we part the Greek’s mythological curtain, let’s set the scene with some of their legends about the Amazons to try and understand how they saw them. They’re clearly fascinated by them. And threatened, and lusty…sometimes it’s a fine line between the two.

Though the Amazons are considered “barbarians”—women from outside the bounds of Greek culture—they also have a legend about one of their own. Once upon a time, King Iasos of Arcadia crossed his fingers that his newborn child wouldn’t be a daughter. When he found himself handed one, he decided it was best to leave her on a mountainside to fend for herself. Thanks, dad! Luckily a mother bear happened by and adopted her, bringing her up in her wild, dangerous world. When some hunters came upon her years later, she was a wild and feral thing: a natural predator who needed no one. She could hunt better than any man around, and wasn’t afraid to do it topless. “With naked breasts she carried her weapons,” wrote one guy, “and did not blush.”

Like Artemis, the Olympian virgin huntress we met in our latest bonus episode over on Patreon, Atalanta loved nothing more than to go roaming alone in the woods with her bow and arrow. She wasn’t about to let any man threaten her independence of either body or spirit. So when a couple of centaurs try to assault her, she does what Artemis would have: she shoots first and asks questions later. See ya, Centaurs! She is so famous for her ferocity that a guy named Meleager invites her to come on an expedition to hunt down the terrible Caledonian Boar. This isn’t just any boar: it’s a beast sent by an angry goddess to ravage the land, and Meleager is rounding up the burliest and bravest heroes to try and kill it, including Jason and his Argonauts and Theseus, the king of Athens. Many of these heroes are not best pleased about having a woman in their party. But Meleager, who has the mad hots for our starring lady, tells them to get stuffed and get over it, because she’s coming along.

Meleager thinking about how beautiful Atalanta looked while spearing the Caledonian Boar.

A fresco from Pompeii, on view at the National Archaeological Museum of Naples.

Off they march, and things get tragic quickly: the boar slices open several members of the party, and then in the confusion some of the hunters accidentally kill each other. But Atalanta keeps her cool. Turns out that she is braver and more skillful with a spear than any of them—and so she’s the one who hits the boar first. Later, a besotted and very impressed Meleager presents her with the boar’s head as a trophy—apparently in ancient Greek art, presenting someone with an animal’s carcass or a severed head is a highly erotic gesture. Sexy.

Meleager and Atalanta by Jacob Jordaens (1620-1650).

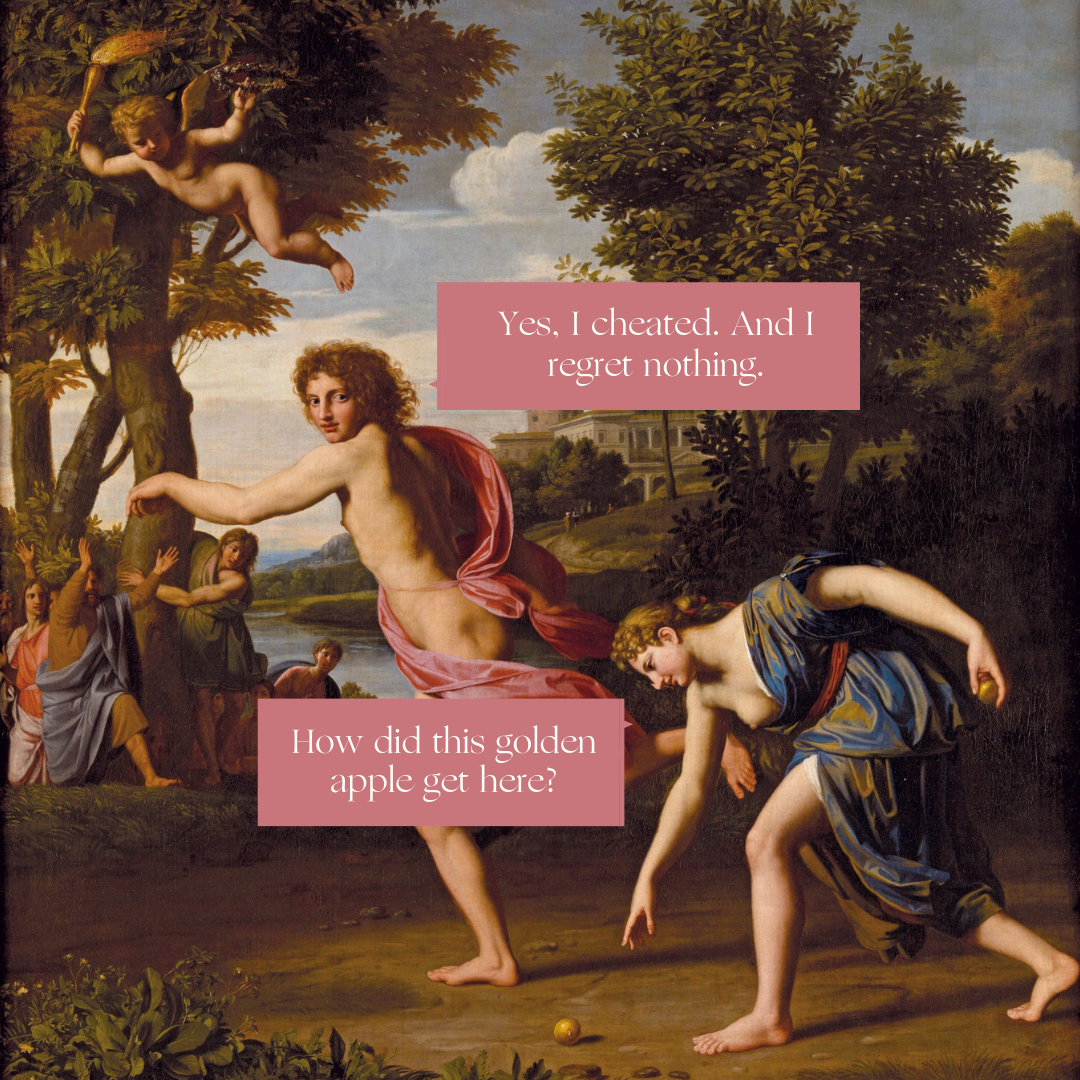

But the other hunters are NOT happy. It’s a disgrace, they say, for a woman to take home the top prize. Jealous much? So Meleager gets frustrated and kills some of them, and later on some of them kill him, and it’s all just…well. Very messy. When Jason and his Argonauts go sailing to look for the Golden Fleece, Atalanta offers to come with them. And though they could badly use her expertise, Jason says no, fearing his men’s reactions. So Atalanta says, “Whatever, losers,” and goes home to her long-lost father and mother. They’re very proud to have her back, despite the whole leaving-her-in-the-woods-to-die business. But this in ancient Greece, so they aren’t keen on her staying single. Atalanta values her freedom, though, so she sets conditions: she’ll marry someone, sure, but only after they best her in a footrace—she’ll even give them a head start! Isn’t that nice? If they win, she’ll walk down the aisle with them. If she wins, then it’s off with his head. Head chopping notwithstanding, MANY men step in to try and win this wily, beautiful huntress, but no one can do it: she’s just too fast. So when amorous hopeful Hippomenes steps up to the plate, he knows he’s going to need some divine intervention. He gets the goddess Aphrodite to give him three golden, magically irresistible apples, which he drops along the trail in hopes that Atalanta will feel compelled to stop for a bite. That she does several times, but even so, he barely beats her—but beat her he does, and she isn’t too mad about it.

Atalanta and Hipponemes racing each other. “Atalanta and Hippomenes” (c. 1699) by Nicolas Colombel.

So far, we’ve seen some familiar ancient themes at play in this story: Atalanta is an object of desire, attractive particularly because she’s a wild thing—but in the end, we see her tamed. But here’s the thing about her union with Hippomenes: it falls well outside of ancient Greek norms. It’s fitting that the name Atalanta means “balance, equal,” because she and her husband ARE equals: they hunt together, scheme together, and have many wild rolls in the hay on their travels. Until one day when they decide to get amorous in a sacred grove, and an angry god turns them both into lions. Because we can’t let her be strong, sexy AND independent! Scholars from medieval times see her fate as some kind of divine punishment for being too free, both sexually and in general, because lions never mate with their own kind. Wrong again, medieval scholars! Perhaps her fate is meant more as a gift than a punishment: a chance to be the wild, free thing she always wanted, hunting with her equal for eternity.

In a society where women are supposed to stay at home and dedicate themselves to the domestic sphere, there’s no room for a real-life Atalanta. And yet she’s very popular, depicted over and over again on vases and the sides of men’s favorite wine amphorae. She’s also a popular subject on women’s perfume bottles and vases designed as wedding gifts. The racetrack she’s famous for beating so many suitors on is actually a tourist attraction, as is the altar at her birthplace, where people pay homage by leaving boar tusks on the altar.

Atalanta’s often depicted wearing next to nothing: a loin cloth and the ancient version of a sports bra. And she’s often wearing clothing associated with the nomadic tribes that the Greeks describe as Scythians: horse-riding peoples who roam the great grass seas of the Eurasian Steppes. The Greeks fetishize such women. They’re fond of wearing tiny cameo rings, set with jewels carved with intricate scenes, meant to be enjoyed by the wearer and their friends. Many of them show Amazons being subjugated by heroes, dresses falling off to reveal their more personal attributes. Some art clearly meant for private consumption shows nude Amazons in suggestive positions. We’ve found a few alabaster vases that show a Greek youth courting an Amazon maiden, one with the inscription o pais kalos, or “the boy is hot.” One of Atalanta “pleasuring Meleager with her lips” was last seen hanging suggestively over the bed of Roman Emperor Tiberius. Later, Emperor Nero develops a fondness for a bronze Amazon statue called “Lovely Legs” that he carts around with him everywhere.

We’ve also found Amazon women made into children’s dolls, suggesting they’re a source of girl inspiration. These dolls have moveable arms and legs and often come with a weapon—Amazon Barbie, minus the plastic heels. We aren’t sure whether they’re meant as toys, or if they’re sacrificed to the goddess Artemis when a girl gets old enough to marry, placed on her altar in a mysterious ritual called the Arkteia (or “She-Bear”). During it, girls run around pretending to be wild bear cubs, just like Atalanta, then sacrifice their dolls to show they’re ready to leave childish things behind.

But maybe, much like the Amazonian Wonder Woman is for us today, the Amazons are hero figures to ancient Greek women—a reminder that the ladies have a deep well of strength to draw from, even if they can’t do it holding a spear. At the very least, they are a subject of general fascination—a window into the life they might have had, if they’d only been born a thousand miles to the east or to the north.

Amazons from outside Greece show up a lot in stories: they tend to ride in from foreign lands to tangle with the mighty heroes of myth. Some accounts of the Trojan War say that the mighty warrior Achilles fell in love with the Amazon Penthesilea right in the midst of battle…while in the act of killing her. “Achilles removed the brilliant helmet from the lifeless Amazon queen,” says Quintus of Smyrna in The Fall of Troy. “Penthesilea had fought like a raging leopard…Her valor and beauty were undimmed by dust and blood. Achilles’ heart lurched with remorse and desire…All the Greeks on the battlefield crowed around and marveled, wishing with all their hearts that their wives at home could be just like her.” Of course, it’s easy to wish your wife was like a raging leopard when she’s no longer capable of brandishing a spear.

There’s also the story of Theseus, king of Athens, who murders the great Amazon warrior Melanippe and kidnaps Antiope from the southern Black Sea coast, bringing her home with him to walk down the aisle. Which Herodotus thinks is fine. “In my opinion, abducting young women is wrong, but it is stupid to make a fuss about it after the event. It is obvious that no young woman allows herself to be abducted if she does not wish to be.” Come on, man!

This outrage prompts the Amazons to get together and march on Athens, surrounding them so no one can get in or out. For months the battle rages around the city. Where is Antiope, you wonder? Some versions say that, well and truly suffering from Stockholm Syndrome, she fights dutifully along her stabworthy husband. But others say she dumps that ass hat and joins up with her Amazon friends.

These stories the Greeks concocted about foreign warrior women tell us a lot about how they feel about them. They tend to involve a great man slaying them, putting these man-killers from the edges of civilization in their place. But they’re not depicted as monsters—ancient Greek myth has plenty of those. In fact, they’re described as heroic. We’ve found over 500 vases with Amazons on them, and almost none of them show one begging for her life. They’re even shown as desirable—a kind of hero, despite the fact that they have lady parts. In the myths, they often have to die in the end.

But they show up in other civilization’s myths, too, often with more satisfactorily amorous endings. They crop up in North Africa, China, Eurasia, Persia, India, and Egypt, suggesting that warrior women are a favorite theme across cultures.

In Iranian tradition, we have a Saka warrior women by the name of Zarina, which means “Golden”, who supposedly lived during the time of the Median Empire. This leader of warrior women is more beautiful and daring than any of them, and considered a hero for how many enemies she slays. The Parthians and the Saka team up when they break away from the Median Empire, and Zarina marries their king, named Mermerus, to seal the deal. In a bloody battle against the Median warrior Stryangaeus, he knocks her off her horse. He then either a) is so struck by her beauty that he lets her remount and gallop away, or b) injures her, and she runs away. Later, when Mermerus captures Stryangaeus. Zarina begs him to be kind, since he let her go earlier, but he’s not having it. So she helps the captive escape, who promptly turns around with some disgruntled Medians and kills the king. RIP, Mermerus. Once all this madness has died down, Stryangaeus goes to visit her in a beautiful city called Rhoxanake. She kisses him openly and rides in his chariot, which causes him to burn with desire. Once he finally confesses his feelings, she’s like, “Um, that’s nice, but you have a very pretty wife, and a whole lot of concubines. I mean, what would THEY say?” So he goes away sulking, about ready to kill himself over the humiliation. But he makes sure to write Zarina a mean letter before he goes: classy. We don’t actually know the end of the story, but we do know that Zarina for sure had the upper hand.

In Egypt, we have the story of Amazon queen Serpot and Egyptian prince Pedikhons which takes place around the 7th century BCE. Apparently this prince invades her all-woman territory of Khor, or Assyria, and they settle down uneasily to camp near each other. Serpot, whose name in Egyptian means “Blue Lotus” and who’s referred to as a pharaoh, calls her ladies into her tent and is like, “we need to pray to our girl Isis” and sends one of her best lady scouts, Ashteshyt, to go a-spying. Dressed as a man, she works her way into their camp without incident, and her intel helps Serpot devise a plan. They attack on horseback and in chariots, all with scary-looking breastplates, and they “call out curses and taunts in the language of warriors.” Finding himself being roundly embarrassed, Pedikhons challenges Serpot to a one-on-one fight. They go at it all day, until the sun starts to set and she’s like, “Listen, we can fight again tomorrow.” And he says, panting furiously, “yeah, okay. I mean, no one likes fighting in the dark.” They start to take off their armor, and they’re both like “ummm, helllllo sexy,” then spend a few hours getting to know each other. Nothing says “I’m into you” like trying and failing to stab each other in the heart. The next day they fight again, and eventually make peace with each other. And when some OTHER army shows up, they fight it together. We don’t have the ending of this one, either, but it seems like some steamy time under a tree somewhere is likely.

And then there’s the Chinese legend of Mulan. When her father is conscripted, she decides he’s too old for the soldiering life, chops off her hair and rides off in his place. For ten to twelve years she fights bravely in her manly disguise, only to eventually meet with the emperor. She tells him she doesn’t want any of his fancy titles or court appointments: in one later version of the story, he discovers she’s a gal and says he’d be totally glad to make her his concubine, an offer she emphatically declines. She just wants just a fast horse to spirit her back home, where she puts on her old clothes and goes about life as a lady.

These tales give us not only strong women, but ones capable of being lovers AND fighters. Take this passage from the Nart Saga from the Caucasus—stories that form part of an oral tradition that comes from ancient Scythia: “In olden times, the earth thundered with the pounding of horses hooves. In that long ago age, women would saddle their horses, grab their lances, and ride forth with their men folk to meet the enemy in battle on the steppes. The women of that time could cut out an enemy’s heart with their swift, sharp swords. Yet they also comforted their men and harbored great love in their hearts…”

Kyz Saikal, a Kalmyk fictional warrior woman heroine of Central Asia.

Image from a postage stamp. Wikicommons.

AMAZONS IN LIFE

Most of what we’ve covered so far are fictional stories, though most Greek writers treat the Battle of Athens as historical fact. They fully believed that some long-ago Amazons attacked them. But they hint at two things: that the ancients are quite fascinated by warrior women, and that there are enough real, flesh-and-blood women who help inspire the tales. We know now that there were women who lived just like the Amazons, hunting and riding, fighting and living on par with the men in their midst. The Greeks call them Scythians: a loose, shifting term for the many different nomadic tribes that live around the Black Sea and to the west, north and east. These fierce nomads live on the Eurasian steppes, extending over thousands of miles through Thrace, Anatolia, Syria and Media, across the Caucasus Mountain to the Caspian Sea and extending all the way into China. In today’s geography, we’re talking Iran, Armenia, India, Russia, Siberia, all of the “stans” – Kazakhstan, Uzbekistan, etc.—Russia and Mongolia. The Persians and Chinese have their own names for them—Saka and Xiongnu. Their way of life on the steppes goes strong from the 6th century BCE to about 500 CE.

Archaeological studies on the Eurasian steppes have uncovered, quite literally, a whole bunch of ancient mounds or graves, called ‘kurgans,’ many dating back to the time of the Greeks. Archeologists have found more than 1,000 tombs across ancient Scythia and the Eurasian Steppes. And while scholars once peeked into them, saw swords, and were like, “yup, this guy was definitely a dude,” DNA allows us to be a little less sexist. One of every three or four of these nomad women were buried with weapons: warriors in life, and honored as such in death. Based on what we’ve found so far, lady warriors represent some 37% of warrior burials.

Analyzing their bodies tell us a lot about how they lived and died: many had wounds that must have been given by some kind of weapon. Unless the ladies regularly took spears to each other in the cooking tent, it’s pretty clear they died in battle. In 2004, we even found two Scythian woman buried in Roman Britain, buried with their horses, bits of ivory and their swords. Which suggests that Amazon-like women were allowed to join the Roman army, which is kind of mind-blowing.

This map gives you at least some idea where the so-called Amazons lived, though their territory was very wide-ranging and stretched very, VERY far outside the average Greek’s world. If you like this map, check out the Exploress Etsy shop: you’ll find the map for sale, and it makes a great conversation piece hanging up in your office or a nice gift for the ancient lady-loving history enthusiast in your life.

AMAZONS VIA ANCIENT GREEK TELEPHONE

But who were these women, and what did their lives actually look like? Most of these tribes didn’t leave any written evidence of their cultures, so piecing it together involves sifting through stories and rumors, legends, poems, and some of the practices that have survived out on the Eurasian steppes.

In our hunt for Amazon women, it’s important to remember that the Greeks aren’t always the most reliable sources. Remember when you used to play telephone? How you’d whisper something from ear to ear that started out as something like “I like bananas,” and always turned into some version of “somebody farted”? The ancient Greek stories about Amazons are kind of like that.

Very few scholars spent time amongst them, so we have very little eyewitness reports from them on these nomadic cultures. Their stories come from people traveling down to Greece from the northeast: traders, explorers—even slaves bought and brought home from these faraway lands.

And the so-called Scythians aren’t just one people, but a whole bunch of tribes that probably speak different languages and have different cultural practices. Since most people in Greece don’t speak those languages, their stories come to us through many layers of twisted whispers. Though we do have a friend in HERODOTUS, the fifth-century writer from Halicarnassus tucked into the Persian Empire near the coast of modern-day Turkey. He actually observes and writes about Scythians, giving us what are some of the only up-close-and-personal accounts of their lives.

Luckily there are plenty of ancient Greeks ready to jump in and sensationalize the Amazon story. Their fanciful facts about warrior women still confuse our view of them today. For example, Diodorus of Sicily writes in the 60s BCE about how Scythian bands are often ruled by women who “train for war just like the men and in acts of manly courage they are in no way inferior to the men.” But he takes it a step further, saying that one Amazon queen near Pontus on the Black Sea coast enacted laws forming a gynocracy, where women would always rule. Women went to war, he tells us, and the men stayed home and sat behind the spindle. Baby girls had one breast seared off to prep them for using a bow and arrow, while baby boys had their legs maimed. Mmk.

Such writers give us the Wonder Woman version of the Amazon story: they live in all-female bands, loyal only to each other and vicious to outsiders, particularly if they happen to have man parts. They roam vast, endless grasslands, almost never getting off their horses, honing their incredible aim by shooting at gemstones and coating their arrows with steppe viper venom, just itching for some man to happen by. They either hate men, or they use them for their own sensual purposes. AND they use the skulls of their enemies as goblets.

Even the term “Amazon” has a confused and foggy history. We’re not sure where the word even comes from. It’s definitely not Greek, but a loanword from another language. The Greeks could have taken the word from several languages – the Circassian name a-mez-a-ne, meaning Forest (or Moon) Mother, the ancient Iranian ha-mazon, meaning “warriors,” while another linguist thinks it might mean “husbandless.” It first appears in the Iliadas Amazones antianeirai, and we aren’t sure what it actually means. It doesn’t have a feminine ending, which dashes the idea that they’re a female-only club. The Greeks tend to highlight whatever is most unique about a particular group of people, which is why we have that second word, “antianeirai.” Taken together, we think it might mean “Amazons, the tribe whose women are equals,” or “Amazons, the equals.” And the Greeks call that out because it’s so outside their norm.

But enough of legend. Let’s leave these old Greek writers behind and step into the grasslands, waking up into the life of a Scythian.

greeks vs. amazons. good luck, boys.

Battle of Greeks and Amazons on a marble sarcophagus, courtesy of the Vatican Museums

A DAY IN THE LIFE

Much of what we know about our lives as Amazon-like warrior women comes from stories written down by people outside their cultures and from examinations of their burial mounds. We have tons of information to sift through, though—enough to piece together what life for an ancient Scythian woman might look like. Though it’s hard for us to spend a comprehensive day as an Amazon because we’re talking about a whole bunch of individual tribes, all with different languages, customs, and beliefs. They go by many names: Sarmations, Massagetae, Cimmerians, Parthians, Saka.

But there are a few things the ancients agree on: all of these groups are nomadic, roaming with their horses over vast, open grasslands. “Lured on by pastures,” says Roman geographer Pomponius Mela, they “live in camps and carry all their possessions and wealth with them. Archery, horseback riding, and hunting are a girl’s pursuits.”

We Scythians don’t tend to stay in one place for long. One ancient historian said that these “warlike tribes have no cities, no fixed abodes; they live free and unconquered, so savage that even the women take part in war.” We’re always roaming, hunting, herding, raising horses, coming together for festivals and funerals, and yes, sometimes to stab a man or two. And that’s the key to a Scythian woman’s freedom, compared to Greek women: their way of life demands equality, and makes room for women to step up and take an active role.

The steppes are made up mostly of grasses stretching for thousands of miles, exposed and lacking much vegetation. If the graves of ancient steppe people have anything to tell us, it’s that this nomadic life is hard. Analysis shows skeletons with many broken bones and dislocations, probably from falling off horses, and hurts clearly made by a sharp blade or arrow. For those who live to a ripe old age, they probably go to the grave with a limp. This challenging nomadic lifestyle means that everyone has to contribute and be flexible about their roles. Men and the women both are buried with spindle-whorls, baking supplies, bows and arrows, suggesting they share the load in terms of who’s hunting down dinner and who’s cleaning the tent. The Greeks are shocked by how much time Scythian women spend out and about. “they keep no watch over maidens,” Herodotus tells us. “And leave them altogether free.”

But the true key to our freedom and equality has to do with the light of our lives: our horses.

ALL THE WILD HORSES

We don’t know exactly when we first domesticated horses, but we think it happened around 3500 BCE in Kazakhstan and the Ukraine. In other words, the places where we so-called Scythians live. The importance of the bond between us and our horses can’t be understated. In a time before cars or engines, they pull our wagons and chariots—they enable us to travel long distances; they ride with us into raids and wars. They give us sustenance and supplies: horsehair, which is as strong a rope as you’re likely to find, hooves, meat, and milk, sometimes fermented to make an alcoholic concoction called koumiss.

In short, we worship our horses and are often buried with them. Our kurgans are full of riding equipment, harnesses, bridles, and many pieces of art in which horses play a central role. They have their own legends, too, and riders are often known by their horse’s name rather than their own. Amazon names reflect how much we love them: Hippolyte, which means “Releases the Horses”, Hipponike, which means “Victory Steed,” and Xanthippe, which means “Palomino.” And as a modern-day horse lover from way back, this is a feature of Scythian life I can get on board with.

While we’re speaking of names, can we pause to enjoy a few others? Many are Greek, preserved on their vases and paintings, but they’re evocative and fairly badass. Lykopis or “Wolf Eyes,” Antianeira or “Man’s Match,” Aella or “Whirlwind”, Charope or “Fierce Gaze.” But some of the names found on ancient Greek vases have turned out to be in their original language, and I am sure to butcher them, but I’ll do my best: Pkpupes, or “Worthy of Armor,” Khasa, or “One Who Heads a Council,” and, gloriously, Kepes, or “Hot Flanks/Eager Sex.” You tell ‘em, sister: loud and proud.

But back to horses. There’s a highly coveted breed of horses, called Akhal Teke, that bear a striking resemblance to the Scythian horses painted onto the sides of clay pots. They first appear in Central Asia, known for shiny coats, small hooves, and an elegant build. The Scythians take great care breeding and caring for their noble steeds. Big deal kings and emperors wage wars to try and win themselves these famous horses. In 339 BCE, ancient writer Justin tells us, Alexander the Great’s dad Philip is so keen that he kidnaps 20,000 of them, plus 20,000 women and children. Not smart, Philly. On the way back to Macedon he’s attacked by another Thracian-Scythian tribe, getting his leg skewered by a spear and his horse killed for his trouble. The great man loses every one of his captives, horses included. I mean, mess with a Scythian and that’s what you get!

Like a baby caribou in the Canadian tundra, ALL Scythians have to learn how to ride as soon as they’re physically able. Otherwise they’ll never keep up with the herd. And unlike, say, carrying giant bags of grain or wielding a very heavy axe, horseback riding is a truly great equalizer. Being good at it isn’t about what biological parts you have, which means that women aren’t at a disadvantage in terms of brute strength. And so women are valued as much as men, and equal with them. And that never fails to get the Greeks all hot and bothered.

The equality seems to extend to our trusty steeds, as well. Some writers say that Scythians prefer riding female horses into battle because, as Pliny tells us: “they can urinate while galloping.” I have NEVER seen a female horse do this, but…we’re going to have to take his word for it.

If you’re a little nervous about all of this galloping off into the sunset, here’s a tip for you. The key to the relationship between horse and rider is touch. Research about the relationship between us and our equine friends shows that we use a delicate and complex language to communicate, turning physical connection into emotional understanding. Horses feel our bodies move and understand how we’re feeling, and vice versa. We Amazons know this to be true because we don’t use stirrups OR a saddle. We’ll either sit on a simple felt blanket or ride bareback. If you’ve never done this, I can tell you with confidence that it requires skill, nerves of steel, a healthy dose of confidence, and a good relationship with your horse. Those are the only things keeping you from faceplanting into those long, spiky grasses. Luckily, we’ve taught our horses to kneel on command. That means they can get down low so we can mount even if we’re injured. Especially helpful when you have no stirrups to hoist yourself up on.

But before we ride, we’ll need to get dressed.

WEARING THE PANTS (AND THE GOLDEN BELT BUCKLE)

While we’re at it, let’s talk about breasts—when it comes to Amazons, we kind of have to. A rumor has been floating around since antiquity that Amazon women chop off one of their lady orbs so as to make shooting a bow and arrow easier. The ancients even say that the name Amazon is bound up in breasts: look at the word Amazones. Because a- means ‘without’ and mazos is similar to the Greek word mastos, the theory goes, the name actually means something like “breastless.”

Some ancient writers even say that Amazon mothers burn young girls’ right breasts off with an iron tool in order to make them, as Pomponius Mela has it, “ready for action, able to withstand blows to the chest like men.” Others suggest that the young, budding breast is just pinched right off. Hate to tell you, boys, but that theory makes you seem like you’re not overly familiar with the mechanics of a lady’s Christmas ornaments.

Think about this theory for, say, 5 seconds, and you’ll see how little sense it makes.

Particularly if you’ve ever shot a bow and arrow. If you have, you’ll know that you have to turn sideways to shoot and pull the string back to around your chin, which means that breasts don’t get in the way of good marksmanship. Sure, if you’ve got a whole lot of breast to deal with, you might have to adjust your style a little, but they’re never going to keep you from being an expert shot. And yet the Greeks and Romans all repeat this single-breasted idea, sinking their heels in for all of time.

It could be that the Greeks misunderstood Amazon outfits. There’s evidence to suggest that some ladies from the Steppe wear leather armor in their youth to bind down their breasts, making riding and shooting easier. I mean, YOU try riding a trotting horse without strapping those ladies down! In Greek vase paintings, Amazons tend to be shown wearing men’s armor, which doesn’t exactly show off womanly curves. Do the Greeks see Steppe women wearing leather armor and get confused about what they have going on underneath?

Here’s another thing about boobs and armor. In modern culture, we often show women warriors like Wonder Woman and Xena wearing “boob armor” – you know, those things that show off a lady’s assets by creating an iron cup for them to rest in. Those make it very clear that breasts are at play, but they make zero sense from a practical standpoint. Most armor comes to a slight point facing out over the chest, as that means any weapon that strikes it is likely to slide off to either side, keeping it away from vital organs. Boob armor is like an open invitation to an eager sword to get familiar with your sternum. It would serve as a little well for pointy things to fall into, and no serious warrior would ever be caught dead wearing that!

While we’re still in the buff, let’s talk about another contentious feature of our bodies: tattoos. Herodotus says the tribes of Thrace, to the northeast of Greece, feel strongly about body art—they think that not having any speaks to a lack of identity. Philosopher Sextus Empiricus tells us that most get their first tattoo when they’re young. Clearchus of Soli, who travels widely through Thrace, says they decorate themselves “all over their bodies, using the tongues of their belt buckles (or pins of brooches) as needles.” Ouch.

As you look down at the horse twisting artfully across your ribs, you remember it: how the design was traced on with a leather stencil, then someone bundled together a bunch of tiny needles and turned us into a human pincushion. After that, they rubbed in some ash-based pigment mixed with tallow, berry juice, or indigo for color, along with some sap of ox bile to make it set. Yummy.

The Greeks are weirded out by such permanent decoration. But to us Scythians, they’re a mark of beauty and social standing. Animals are a favorite: horses, antlered deer, tigers, imaginary beasts like griffins, all twisted and contorted into incredible shapes and artful angles. And though we have accounts of men having tattoos, they seem particularly tied to the ladies. Archeologists have unearthed tattoo-covered female forms made of clay on the Steppe and Neolithic horse bones carved to look like a woman’s torso, also covered in swirling designs.

And then there’s the mummy we call the Ice Princess. In 1993, on the Ukok Plateau in Russia, researchers will find a tomb left untouched for 2,500 years. It will contain a larch-wood coffin decorated all over with large deer, and inside, a perfectly frozen warrior woman with a prominent blue tattoo. In 2003, we’ll discover other mummified Scythian bodies with tattoos still worked into their skin, revealed by that modern wonder called infrared.

Before we pull on clothes, we might oil up with the juice of a plant called halinda, which is said to help protect us from the elements. Life on the Steppe can get mighty cold. Its analgesic qualities may also help with our arthritis, common to a people who spend most of their lives on, and falling off, horseback. As we dress, we might put on a range of jewelry, depending on our purpose. We roam far, we Scythians, trading with cultures far and wide, and our art reflects this. We might wear gold rings or earrings, bits of jade, or even bracelets made of fox teeth, and then gaze at ourselves in bronze mirrors to make sure we’re looking our best. The Ice Princess was buried with a silk wrap, a huge headdress, and thigh-high embroidered boots. Killin’ it in the afterlife!

Reports vary on what exactly we’ll be wearing. Herodotus says the Thracians wear fox-skin caps, tunics, colorful cloaks and fawn-skin boots. Guys like Plutarch suggest that much of our clothes are made out of animal skin, while Roman historian Ammianus Marcellinus says we wear a hemp tunic and leggings made of rodent and goatskin. Rat leggings, anyone? Those’ll go over great in your Sunday morning yoga class!

It’s likely we’ll wear leather to protect us from the cold and for riding. In Greek art, a common feature of our outfits are our pointy felt caps and long-sleeved tunics, along with a belt and some splashes of gold. If our grave goods are anything to go by, we like to deck our horses and ourselves out in things that are shiny.

It’s likely that, much to the ancients Greeks’ consternation, we’ll be wearing pants. It makes sense that Scythian girls and boys alike grow up in them, as they help protect our skin from the wear and tear of riding, and they’re practical for a life where everyone’s expected to hunt and work.

We don’t know when pants first appeared on the scene: the earliest trousers we know of were dug up in the Tarim Basin, dating to 1200 to 900 CE. But the Greeks give Amazon women credit for their invention—which may be one of the reasons they find these women so upsetting. A lost history by Hellanikos says that a great Persian queen named Atossa is the first to wear them. “Disguising her feminine nature, Atossa ruled over many tribes and was most warlike and brave in every deed.” Semiramis, whose legend dates to around the ninth century BCE, is also said to tell all her subjects to wear them in an attempt to blur any distinctions between men and women. Pants: a great liberator, and practical for a life on the move. This is a huge deal to the Greeks. First, because they make it hard to tell who’s male and who isn’t. Second, and most interesting of all, because the Greeks consider pants effeminate.

Even Alexander the Great, huge fan of adopting styles of dress from other cultures, refuses to wear them. Yes, because that Grecian minidress and no underwear situation you’re riding around in makes SO much more sense.

Our pants are made of all sorts of materials: leather, wool, flax, hemp, even silk. Hugh Hefner would no doubt approve! Though the silk is probably worn under other, hardier layers. Which is good, because if our promiscuous rep is anything to go by, we’ll be peeling those layers off for someone later.

Pants on and shiny ponies ready, we’ll leave our Amazon day for now. Next week, we’ll dive into some other aspects of our lives as Scythian women, from hunting and battle to what we do for fun, including open-air nude frolicking and marijuana saunas. And we’ll meet some of the historical women who fueled the Amazon myth and gave women warriors such a fearsome reputation.

Scythians shooting with bows, as they do.

4th century BCE. Wikicommons

PART 2

When we left off last episode, we were pulling on our silk underthings, strapping on some leather, and getting ready to go about our Scythian day. If you haven’t listened to part 1, I’d go and do that before listening to this one. Otherwise, let’s hop onto our horses and ride. While we’re trotting along, let’s talk about a controversial and convoluted subject: our sex lives.

SEXY TIMES

The Greeks have a lot of contradicting views about them, we need to return to the Amazon myths. If we’re known for two things, it’s sex and violence. Amazon sexual appetite is described in one of two ways, at least in Greek literature. Some guys like Aeschylus call them “maidens fearless in battle,” so some scholars purport they’re staunch and militant virgins. We tend to think ‘maiden’ as meaning virgin, but in ancient Greece it actually just means ‘unmarried.’ There are several Greek goddesses who shun sex and kill men who try to steal away their V card—Artemis and Athena, both hunters. Perhaps one of the Amazons’ nicknames, “androktones” or “man-killers,” stems from that.

Some paint them as hating sex and everything associated with it. Jordanes says that “among the Amazons childbearing was detested although everywhere else it is desired.” Go jump off a cliff, Jordanes. And there’s the rumor that Amazon women hate men so much that they kill baby boys when they’re born, exposing them to the elements, or maiming them. Others say the boys are handed off to be raised by fathers in separate settlements, supposedly because they value them less.

So are the Amazons all battle-scarred bands of women warriors who sleep with men only for procreation and kill them directly afterwards? Unlikely. It is likely that some of these semi-nomadic tribes see their menfolk ride away to raid for long periods, Dothraki-like, and thus often have to fend for themselves. If an ancient Greek stumbles upon us in this state, it would be easy to see why he’d think we are an all-lady tribe. Some ancient writers make it seem as if Scythian men and women live separately, only coming together a few times a year to make babies and, if they’re boys, hand them over to their fathers, but we don’t have any reason to believe this is so. It’s also possible that some groups practice “fosterage”: exchanging kids between clans to form alliances between them. But it’s unlikely any Scythian woman are throwing boys out the proverbial window.

Other writers offer up a different version of the Amazon sexscape. Several describe them as “man-loving,” not man-hating, painting them as wanton swingers who bed down in the grass with whomsoever they please.

Herodotus gives us the following story: long ago, before his time, a tribe of female Amazons were taken prisoner by Greeks and put onto their ship. The Amazons, knowing they’d be turned into slaves, rose up, grabbed their spears and killed them all, because obviously, then landed the ship in Kremnoi on the Sea of Azov. They promptly found some horses and stole them, then went about pillaging all and sundry. The local Scythians, called the Royal Scythians, once lived a nomadic life, but had long since bedded down in semi-permanent settlements. And they were not best pleased with this band of feral foreign ladies. So they sent one of their young men on over to negotiate.

But since they couldn’t speak each other’s language, progress was slow. Eventually, the Amazon woman made enough obscene hand gestures that the Scythian understood what she was throwing down: that she was down for some connubial communion if he was. So they made love instead of war, right there in the grass. Afterward, she used her skills with sign language to intimate that he should come back the next day and bring a friend, which of course he did. More friendly boinking ensued.

For a while, the Amazons and these Royal Scythians were happy just laying and playing together. The men never bothered to learn their language, but the women learned to speak some of theirs. Eventually that first guy said, “hey, babe, this whole nude orgy in the grass situation is super fun, but maybe you ladies could come on over to our place and settle down to make babies and bake bread and stuff?” Or, as Herodotus puts it: “We have parents and property…We promise to keep you as our wives and we will not take up with any other women.” Really selling it, Romeo! The Amazon replied: “Impossible! We live to shoot arrows, throw javelins, and ride horses…Your women never leave home to hunt or explore or for any other reason. We would never be able to live like that.” Fair enough, I say.

The ladies proposed the men give up their settled lives of luxury and gallop away into the sunset with them. And the guys were like, “Yeah, cool. Sounds hot.” And together they formed a merry band called the Sarmatians, which were still roaming around in ancient Greek times.

But how many casual carnal encounters are we really having? It’s hard to say. We migrate a lot, moving with the seasons, but tribes do come together in spring to bury the preserved remains of our loved ones and take nice, long, purifying saunas. We also mingle for trading purposes and compete in riding and shooting contests: all great opportunities to knock Scythian boots with someone new. And why limit yourself to just one, anyway? Strabo tells us that the women of the mountain tribes of Medea in modern-day Iran “believe it honorable to have as many men as possible, and consider less than five a calamity.” Herodotus tells us that the Agathyrsi mate with whoever they feel like to help “foster sibling-like relationships and to eliminate jealousy and hatred.” The clan who gets nude together stays together! And, of course, they may also see the wisdom in mixing up the gene pool a little, though they wouldn’t think of it along those lines.

Amongst the Massagetae, whose queen we’ll meet a little later, open marriage is a definite option if done discreetly. Instead of a sock on the door, the sign for “busy please go away” is a quiver sitting outside a lady’s wagon. Slay girl, slay!

Herodotus tells us that Amazons do indeed get married, and consider that a sign of a life well lived, but not before they prove themselves in battle. Pomponius Mela says that “to kill the enemy is a woman’s military duty and virginity was the punishment for those who fail.” The historian Aelian says that amongst the Massagetae, courtship itself is a battle. “If a man wants to marry a maiden, he must fight a duel with her. They fight to win but not to the death. If the girl wins, she carries him off as captive and has power and control over him, but if she is defeated then she is under his control.” This control is probably symbolic: much like Atalanta, we women of the Steppe are interested in finding a partner who is our equal. Nothing says “you get me” like a guy who isn’t afraid to go against you in a savage wrestle. Couples are often buried together, equals even in the afterlife.

All we can really be sure of is that Scythians are enjoying the pleasures of the flesh, either with one or several someones, and they’re probably doing it way more on their own terms than any ancient Greek wife. And unlike them, Scythians can expect to be treated as their companion’s equal. This barbarian life is looking better by the minute!

AMAZONS IN BATTLE

Now. Let’s get into some violence, shall we?

Though we tend to think of Scythians midbattle, much of what we use our weapons for is hunting. In a life when we don’t stop much to farm, meat features prominently in our diets. All sorts of hunting trophies have been found in Scythian graves, from boar’s tusks to lion claws, which shows how very far we can roam.

We often take dogs along when we go hunting. We use eagles, too, which ride on our arms clutching thick leather mits. Dog, horse, body art, pants, eagle…are you excited to be a Scythian yet?

We often skirmish with other tribes. As Lucian of Samosata from Syria tells us: “Scythians live in a state of perpetual warfare, now invading, now receding, now contending for pasturage or booty.” We are sure to carry a lot of pointy objects, always ready to take aim and fire. According to the Greeks, we Scythians are the first to make iron weapons: one of the many reasons we slay so hard. But our weapon of choice is the bow and arrow: we are famous for our accuracy and range. Shooting an arrow far and fast isn’t all about strength, either, but skill. And we’re using recurve bows, which are compact and energy efficient, smaller, lighter, and more powerful: perfect for a fast-moving horsewoman. They look a bit like the Greek letter Sigma. Imagine a bow whose ends curve away from the archer when it’s left unstrung.

They take years to make: first you have to coat a wood frame with layers of horn wrapped with horsehair or bark and glue, then you have to leave it to season. Every Steppe nomad has one, and it’s precious: not something you’d leave lying around. Our quiver is two feet long, decorated with gold plates worked with special designs, and hangs from our hip, ready to supply us with arrows.

We think they are probably firing some 15 to 20 arrows a minute with crazy accuracy up to, say, 200 feet. Though a fourth-century inscription praises a woman warrior for shooting an arrow some 1,700 feet. That’s longer than the Empire State Building!

A terracotta lekythos (oil flask), ca. 440 BCE, showing an Amazon using a slingshot. Seriously: this is not a toy, okay? It’s all fun and games until someone loses an eye.

Attributed to the Klügmann Painter. Courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

A big part of our success as warriors is our ability to shoot a bow and arrow while galloping. Our horses are bred for both speed and endurance, and after a lifetime of practicing shooting at speed, we’re quite a formidable duo. Particularly terrifying is a move called the “Parthian shot” where we turn backward on our horse as we race away, pretending to be fleeing, then turn and shoot at whoever’s behind us. Imagine that: you, on a horse galloping at many miles an hour, twisting 180 degrees and shooting someone through the heart with the wind ripping your hair out of its braid.

We also carry battle axes, sometimes with a bronze head: not the kind of thing you want flying toward your cranium. Swords, daggers, spears, knives in bronze and iron – we never leave home without them. There’s even evidence that we might lasso our victims, a la Wonder Woman and her shiny Lasso of Truth. Herodotus tells us that, with only daggers and these lassos, Scythians go about breezily “killing the victim entangled in the coils of the noose.” Indiana Jones meets Xena, Warrior Princess: You can see why the Greeks find us enthralling and terrifying.

We also use ancient slings. Think the slingshots you may have grown up playing around with, with long-distance range and the power to take out an eye, and maybe some brains, with chilling efficiency.

We carry shields, usually a half-moon or oval made of wicker, leather, wood or bronze. We’re also fond of huge, fancy war belts. These are such a magnificent and regular feature that they may have inspired the Greek myth about Heracles going after an Amazon’s fancy belt, called the Belt of Ares, and ending up in a bloody skirmish for it. I mean, just because we’re going to battle, doesn’t mean we can’t look fabulous doing it.

Herodotus says that they often keep gold cups dangling from them: we don’t know why they’re there, but we have some ideas. Maybe they were there in case we need to make a binding pact, called a blood oath, where we cut ourselves and drink some blood. Or maybe they hold the poison we’re rumored to dip our arrows in. Either way: pretty hardcore.

RELAXATION TIME

When it comes to our relaxation time, apparently Scythians are quite fond of a sauna. Herodotus tells us that while not on the move, we often take a kind of vapor bath, which happens inside felt tipis full of large, hot stones. I once spent an afternoon in a sweat lodge that sounds a whole lot like this, and so I can say with confidence that if you don’t like confined spaces and aren’t down with being trapped in temperatures about the same level of intensity as the planet Mercury, this may not be for you.

After that giant sweat fest, we might enjoy some recreational herbs.

Let’s set up a little felt teepee and have some herb-sponsored fun, shall we?

The six sticks of a smoking tent frame and a brazier, Pazyryk 2, late 4th-early 3rd century BCE. From the State Hermitage Museum, St Petersburg, courtesy of the British Museum.

The drugs of choice around the fire are fermented mare’s milk, called koumiss today, and still drunk in places like Kazakhstan, and cannabis. Like ancient beer, koumiss is great for we ancient ladies because it’s full of lots of vitamins and easy calories, and we’re working out enough that we need lots of those. But it’s also good for stirring up the party. A traveler who spends time on the Steppe around 1250 CE, says it “makes the inner man MOST joyful!”

We use herbs, too, to find our jollies. Saka-Scythian tribes use plants called haoma and soma: we’re not sure what they are, but they’re probably not far off from ancient marijuana or magic mushrooms. Pliny tells us that around Pontus, tribes collect a neurotoxic honey from the poisonous rhododendron and turn it into a kind of mead. Which sounds like something we time travelers might want to drink very slowly. Hemp originated in Central Asia and was one of the first plants to be domesticated, so it’s probably easy enough for us to come by. “A plant called kannabis grows in Scythia,” Herodotus tells us, and we “weave garments from it that are just like linen.” He’s not clear on the details in terms of which part of the plant we get high with, but he feels pretty confident we let it burn over the fire and then inhale the fumes. “They keep adding more fruit to the fire and become even more intoxicated—they get so drunk on the smoke that they jump up and dance and sing around the fire.” Sometimes we even do this in the felt sauna tents we’re so fond of, hot boxing ourselves until, as Herodotus puts it, we “howl with joy, awed and elated by their vapor-bath.” Some of us are even buried with a little hemp kit, just to make sure we’re prepared to party in the afterlife. So it may have just been about recreation, or it could have some religious significance, too.

There’s bound to be dancing and singing of an evening, too—jubilation and communion. A celebration that we’ve made through another day as independent, hard-riding free spirits, free under a big sky full of stars. And then, when we’re ready for bed, we might go through a few of our favorite beauty regimens. We’ll mix up a mask of cedar, cypress, and frankincense and apply it all over before hitting the sack. How we’re keeping said mixture from seeping into our sheets is unclear, but apparently when we wake up our “bodies are steeped in the sweet fragrance and their skin is clean and glossy.” Smile, Scythian lady: it’s been a pretty good day.

It’s easy to see why Scythian women make such fierce and frightening figures; why they populate so many stories and myth. But the truth is that, outside of Greece, warrior women really aren’t all that uncommon. So let’s meet some of the REAL Amazon women who make the ancients tremble.

THE REAL DEAL

To start, let’s meet a warrior named Fue Hao. Over in China, at the same time Achilles and Penthesilea are going at it at the battle for Troy, a warrior woman named Fu Hao is born. This queen of the battlefield, whose name means “Lady Good,” arrives in the world during China’s Bronze Age, the daughter of a chieftain of a northwestern tribe. When she turns 15, he sends her to the king of the Shang Dynasty, We Ding, as a present for his growing harem. Amongst a sea of some 60 different wives, Fu Hao uses her charm and quick mind to swiftly become his favorite lady, then uses her forceful personality to become her era’s most powerful military general. With thousands fighting under her banner, she leads a huge army and enjoys even huger victories. He’s so impressed by her skill that he gives her a fiefdom on the borders of the kingdom to both protect. When she died, her tomb was stuffed full of jade pieces, huge bronze vessels, 27 knives, and 16 sacrificed war captives. Which tells you something about the woman she was.

Let’s move over to the northeast a bit and meet a warrior queen named Tomyris. She leads the Massagetae, a free-loving, horse riding people who are big on equality. They sacrifice their horses to the sun and wear helmets and glittering belts in brass and gold. And they aren’t afraid to battle for what they consider theirs, even when it means she has to go up against Cyrus the Great of Persia.

Here to help tell her story is Pamela Toler, author of the fantastic book Women Warriors: An Unexpected History.

At about 530 BCE, Cyrus the Great controlled the largest land empire to date. And the next obvious place for him to take was the area that Tomyris controlled.…And at the point that Cyrus the Great was ready to expand into Tomyris's territory, she ruled alone. And she’s squatting on prime real estate, so it’s the perfect time for this powerful man to move in. He decides the best thing to do with a powerful woman is try to make her marry him so that he can take her land without chopping any heads off. Seeing this move for the power play it is, she declines, writing him a note that goes something like this: “Listen, you’re cute and all, but how about you just go ahead and run your country and leave me here to run mine.” But of course, he doesn’t.

He brings his army up to the river that divides their territory and his men began to build bridges across the river with obviously something other than peace in mind. And Tomyris reaches out and suggests that she and Cyrus meet one-on-one, that he call off the bridge building, and that either her people could retreat by a distance of several miles so that he could come over safely to talk to her or she would come to him. To his credit, he actually took that suggestion to his war council. But they knock it right down: it would be way too shameful for him to capitulate to a woman. They’re going to regret that opinion later.

drink it, B*tch.

Tomyris Plunges the Head of the Dead Cyrus Into a Vessel of Blood by Rubens, Wikicommons.

And so the war between them begins. And at first it's purely a defensive war on her part. She's trying to keep control of her territory, to keep the Persians out. That was fine...until her son died. Cyrus sets a trap for Tomyris’s warriors, setting out a feast complete with wine and then abandoning it. His hope is that these barbarians will stop, as they’re big fans of plunder, and since they aren’t familiar with wine, they’ll get properly drunk, making them ripe for the plucking. Once they’ve fully sunk into their cups, Tomyris’ son and his war band are ambushed.

Now he may have been easily trapped by a banquet, but he had a clear sense of the power politics involved. So he convinced Cyrus to let him be unbound and then he killed himself so he couldn't be used as a bargaining chip. And at that point, it got personal. Tomyris sends him a scathing note letting him know that she’s going to destroy him. “Glutton for blood! … Leave my land now, or I swear by the Sun I will give you more blood than you can drink.”

There is a mighty battle: Herodotus, who is our main source for this, describes it as "the most violent battle of all time." In his innocence, he couldn't imagine some of the violence that would come later. And they didn't take any prisoners. They just killed everyone, including Cyrus.

After the battle’s over, Tomyris walks out into the fields looking for her old friend Cyrus. When she finds him, she makes sure he’s decapitated. Then she dips his head in blood that’s supposedly been drained from Persian soldiers and tells his severed head that, just as she promised, he's now had more blood than he could drink.

Rumor is she later uses his skull as a drinking goblet. That is so SERIOUS Game of Thrones action.

In 480 BCE, a Carian queen named Artemisia I is ruling from the coastal city of Halicarnassus. And though technically Greek, she takes to the high seas in the name of a Persian king. This queen of Caria supposedly wears male-style Persian dress and carries around a dagger and sword, already ready for action. And she knows how to use those weapons, too. The Persian king, Xerxes, is still mad at Greece for a battle he lost, so he rounds up his supporters and sets about invading them. This is the same guy with the scary nose ring who fought the Spartans at Thermopylae: not someone you’d want to face down, if you can avoid it.

Artemisia sails five ships to his banner. And though she has a grown son who could have done it, she’s the one who goes, because as Herodotus puts it, “her own spirit of adventure and her manly courage were her only incentives.” She is Xerxes’ only female admiral, and when he convenes his war council, she tells him it isn’t smart to attack the Greeks at sea. But much like a man who refuses to ask for directions, he chooses not to heed her advice. And so he loses, but not before Artemisia has the chance to fight bravely in battle. Trapped on one side by Greek ships with shiny battering rams, she decides to run into one of Persia’s own ships to try and break a path through to safety, sinking it. Convinced she’s switched sides, the Greeks leave her alone, and thus she escapes. Boys, bye! When Xerxes sees her, thinking she’s just rammed one of the Greeks’ ships, he throws up his hands and says: “My men have turned into women, my women into men.” So dangerous is she that the Greeks offer ten thousand drachmas for her capture. Good luck chasing this badass down.

This is kind of like where’s waldo, exCePt better: where’s artemisiA I?

The Battle of Salamis by Wilhelm von Kaulbach, Wikicommons

Though not a nomadic wanderer, per se, the Greeks consider women like Artemisia II a kind of Amazon: a warrior woman who isn’t afraid to march off into war. Around 350 BCE this queen ruled over Caria, a semi-independent area in the Persian Achaemenid Empire, from the powerful city of Halicarnassus. She’s known primarily for how hard she grieved her brother-husband Mausolus: she’s said to have missed him so much that she mixed some of his ashes into her daily drink. She also built him the world’s most gigantic mausoleum – it’s where we get that word from – which became one of the seven wonders of the world. She even decorates the thing with etchings of Amazons!

But while she’s crying into her ash-filled cup, she also does a bit of Amazonian warring. When she becomes queen after Mausolus dies, the island city of Rhodes decides they’re not down with having a woman ruler, so they send a fleet against her. No matter: she quickly gets archers up on the city’s walls and hides her own ships full of soldiers in a secret harbor. She then gets the citizens to hail the arriving heroes, singing their praises for liberating them from the wicked witch. Once they’re in the city, she raises a hand and has her archers destroy them. But she doesn’t stop there. Artemisia puts her men onto the Rhodian ships and sails them right back to Rhodes, draping the vessels in laurel wreaths, the universal sign for victory. The people of Rhodes, thinking they’re waving at the men returning home victorious, welcome them in, and she has their leaders killed. Do not mess with a warrior woman in mourning.

So who were these warrior women, really? These so-called barbarian women who weren’t afraid to fight for their lives and their lands? Were they blood-drinking, venomous man-haters? Virginal Amazons on a quest to raid the world? The Scythians were neither: they were women living life as they had always lived it, riding with the wind at their backs. But the Greeks told many outrageous stories about them, probably because they were trying to make sense of them. They couldn’t quite fathom the idea of a woman riding into battle: all these years later, many of us still struggle with it. But when you walk through ancient history, women are always there in war, even if they aren’t fighting: their towns sacked, their freedom stolen, taken as slaves against their will. And so I like knowing that some of them grew up knowing how to fight and weren’t afraid to. That they grew up not knowing what it was like to be ordered back into the cooking tent.

I wonder: how many women in Athens daydreamed about Amazons, filled with thrill and wonder? How many of them looked at their images on the sides of their wedding vases and felt a little bit more powerful: just a little more wild? And there were plenty of real-life examples of warrior women for them to feel inspired by: this may be the first time we’ve run into them this season, but it’s far from the last.

Until next time.

music

To hear the amazing music featured on this episode (“The Sack of Troy,” “Ancient Lyre Strings,” and “Procession of the Olympians),” all composed on recreated lyres of antiquity, check out Michael Levy.

voices

Kaitlin Seifert

Avery Downing

Philip Chevalier. To hear his lovely voice in a more musical context, check out his music at The Ellis Temper.

John Armstrong

Shawn from Stories of Yore and Yours

Nathan and Katy from Queens Podcast

Jenny from Ancient History Fangirl