When In Rome: A Lady's Life in the Ancient Roman Empire

You weave our way down a dusty street, trying to get your bearings.

You move past shops full of customers and bright stalls full of produce, past public baths and the shouts from the Coliseum. You skirt past a shrine and a slave market, too. It is loud, busy, bustling, humming with industry and ambition. Everyone here wants to rise to some kind of greatness—to grasp what power they can. And though you’re a woman, you aren’t exempt from dreams of glory. Your path toward it might look different than the men around you, but that doesn’t mean you can’t make a name for yourself here. After all, this is your city. This is ancient Rome.

In this chapter of Season 2, we’ll meet the women who lived amid this ancient-world juggernaut. Many are Roman citizens: the wives and daughters and sisters of influential men who use every tool at their disposal to leave a lasting mark on their fast-changing world—and to survive its cutthroat rules about what women were allowed to do and be. Others are foreigners who refuse to bow to the ever-expanding Empire, fighting against it with both cunning and spears. We will explore the events and laws they had to navigate, the intrigues and wars in which they had a hand. And as always, we’ll try to understand what life was like in ancient Rome for women: what did it look like through their eyes? Lucky for us, we have some expert time traveling companions:

THE PARTIAL HISTORIANS: Hi. I'm Dr. Rad. I'm a specialist in all things Spartacus and historical films. And I am Dr. G. I'm an expert on ancient Rome, particularly ancient priestesses. And then even more particularly, the Vestal Virgins. And together we host a podcast called The Partial Historians.

DR. EVANS: I'm Dr. Rhiannon Evans, I'm the associate professor of Classics and Ancient History at La Trobe University, and I'm the main guest on the podcast Emperors of Rome.

Grab a really long sheet and a few vials of poison…just in case. Let’s go traveling.

This map shows how the Roman Empire grew over the years and highlights some of the women who fought against that expansion. You can buy a copy of this poster at my Exploress shop! Just go to the Store page.

MY SOURCES

BOOKS, MAGAZINES AND SCHOLARLY ARTICLES

A Day in the Life of Ancient Rome. Alberto Angela, translated from Italian by Gregory Conti. Europa Editions, 2015.

30-Second Ancient Rome. Edited by Matthew Nicholls. Ivy Press, 2014 (and the awesomely illustrated kids version…) Ancient Rome in 30 Seconds. Simon Holland. Ivy Kids, 2016.

Maenads, Martyrs, Matrons, Monastics: a sourcebook on women's religions in the Greco-Roman world. Ross Shepard Kraemer, Fortress Press, 1988.

Dress and the Roman Woman. Kelly Olson, Routledge, 2008.

Rise and Fall of the Roman Empire. National Geographic Special Edition, 2014. I believe they’re reprinting this very soon, so keep an eye out at your local newsagent or grocery store!

Atlas of the Roman World. National Geographic Special Edition, 2020. The cool thing about being a nonfiction editor is that I often get to see these gems before you do: sorry not sorry. This one’s great. Keep an eye out for it at your local newsagent or grocery store!

Women’s Life in Greece & Rome. A source book in translation. Mary R. Lefkowitz and Maureen B. Fantasias, 2nd Edition. Duckworth, 1992.

“More Than Matrons: A New Age for Roman Women” by Maris Isabel Nuñez, National Geographic History Magazine, 2018.

“Cosmetics in Roman Antiquity: Substance, Remedy, Poison.” Kelly Olson. The Classical World, Vol. 102, No. 3 (SPRING 2009), pp. 291-310. The Johns Hopkins University Press.

“Virginity and the Place of Virgins in Greco-Roman and Early Christian Society.” A thesis by Kelsi Dynes, Utah Valley University, Dec. 2018. THANKS, KELSI!

PODCASTS

If you want podcasts about the ancient Roman world, you’re living in the right time period. These are all really excellent, and below I’ll tell you why.

The History of Rome by Mike Duncan. If you don’t know Mike, you must not listen to history podcasts…he was one of the first and the greatest, telling the story of the Roman empire in a super engaging narrative that unfolds over many episodes. He doesn’t talk a LOT about the ladies, but that’s fine: I have that covered. Listen to us both and you’ll be pretty well versed.

Emperors of Rome by our special time-traveling companions for this episode, Dr. Rhiannon Evans, and her host Matt. What DOESN’T Rhiannon know about ancient Rome?! Between Matt’s thoughtful questions and her thoughtful answers (and ones from the occasional guest), you’ll get an academic, but very engaging deep dive into ancient Rome and its many facets of life and interesting characters.

The Partial Historians by our special time-traveling companions for this episode, Dr. Rad and Dr. G. These ladies are fun to listen to – very engaging, and clearly so passionate about the subject matter – as they tell the story of the Roman Empire and delve into specific topics with a variety of guests. They are very fastidious and lovely. They even provided this list of resources for the chat we had:

[All available at Lacus Curtius: see entry under ONLINE below]:

Appian, Civil Wars

Plutarch, Life of Tiberius Gracchus

Plutarch, Life of Gaius Gracchus

Plutarch, Life of Antony

Other sources:

Bauman, R. A. 1992. Women and Politics in Ancient Rome.

Bonfante, L.; Sebesta, J. L. 1994. The world of Roman costume.

DiLuzio, M. J. 2016. A Place at the Altar: Priestesses in Republican Rome

Freisenbruch, A. 2001. The First Ladies of Rome: The Women Behind the Caesars.

Greenfield, P. N. 2012. Virgin Territory: The Vestals from Republic to Principate. Dissertation, University of Sydney

Fagan, G. G. 1999. Bathing in Public in the Roman World

Killgrove, K.; Bond, S. 2015. ‘Caesar Undressing: Ancient Romans Wore Leather Panties and Loincloths’ Forbes Magazine.

Murdarasi, K. 2019. ‘The Woman Who Would Be King’ History Today.

Nielsen, I. ‘Thermae’ Brill New Pauly - accessed 2/11/2019

Olson, K. 2008. Dress and the Roman Woman: Self-presentation and society

Ward, R. B. 1992. ‘Women in Roman Baths’ Harvard Theological Review 85.2: 125-47

ONLINE

LacusCurtius is a great place to find detailed information about all sorts of Roman-related business.

Perseus Digital Library, Tufts University. This site is an amazing resource if you’re looking to access translations of ancient source material. It offers access to a huge database, and I sourced and checked all of my ancient sources through it!

Ancient.eu is always a great place to start with ancient online research. Here’s a link to an article about everyday life in Rome.

“Caesar Undressing: Ancient Romans Wore Leather Panties And Loincloths” by Kristina Killgrove, Forbes.com, 2015.

“Clothing for Women and Girls.” Classics Unveiled.

“Aqueducts: Quenching Rome’s Thirst” by Isabel Roda, National Geographic Magazine, 2016. I think it’s pretty great that they let you access so many of their print articles online!

“Roman Plumbing: Overrated. Ancient Rome’s toilets, sewers, and bathhouses may have been innovative, but they didn’t do much to improve public health.” Julie Beck, The Atlantic, Jan. 2016.

“True Colors: Archaeologist Vinzenz Brinkmann insists his eye-popping reproductions of ancient Greek sculptures are right on target.” Matthew Gurewitsch, Smithsonian Magazine, July 2008.

“Vestal Virgins: Rome’s Most Powerful Priestesses.” By Elda Biggi, National Geographic History, Dec. 2018. This article has some wonderful accompanying images and graphics that I couldn’t get the rights to show you below, and it’s a great read.

“Women’s Fashion in Imperial Rome.” Women In Antiquity blog, posted on April 15, 2018 by cmcgowan4

who says that the ladies aren’t meant for the gym?

Bikini girls mosaic, Villa del Casale, Piazza Armerina, Sicily, Italy, Wikicommons

TRANSCRIPT

I CHOP AND CHANGE AS I RECORD, SO THE audio WON’T BE A PERFECT MATCH FOR THE TEXT BELOW. IT’S VERY LIKELY THERE ARE TYPOS, too - I DO MY BEST, BUT when it comes to getting an episode up something has to give, ya know? also, the quotes in bold are ones I’ve made up for the drama, so please don’t quote them in your high school history paper as fact!

Though we have plenty of marble busts of ancient Roman women to stare at, what we know about their lives and times is far from cast in stone. Our sources for how they conducted themselves day to day rely on ancient writers, pretty much all of whom are men, and whose attitudes and agenda are not always female-positive. When they’re not shoving women to the sidelines of their histories, they’re either demonizing them for their wanton ways or putting them up on a glittering pedestal, presenting us with what a woman SHOULD be. We have other sources to draw from: there’s archeology, tombs and ancient art, though even these give us a specific, and not always generally applicable window. So while we walk through the Roman world, trying to see it through the eyes of a woman, keep in mind that the ground beneath our feet is often more sand than sandstone. Take everything with a healthy dash or two of ancient salt.

THE SHAPE OF YOU (ANCIENT ROME)

As with all the ancient empires we’ve traveled to so far, we need to define what we mean by “ancient Rome.” We’re covering a lot of ground here: the Western Roman Empire starts to take shape around 753 BCE and continues on until 476 CE. And the Eastern Roman Empire continues on for quite a while after that: around another thousand years. That’s some two thousand years of Roman goodness to cover, and of course our lives are going to change depending on where we land within it. So let’s take a hop-skipping tour down ancient Rome’s timeline, getting a lady bird’s-eye view of the civilization we’ll soon be walking through.

Ancient Rome starts out as a kingdom around 753 BCE. How the city was founded is a matter of much debate. Let’s linger over this for a minute, as it sets the scene for our understanding of the Roman psyche, and particularly how it views its women. Unsurprisingly, the Romans have a pretty dramatic legend about their founding. The story goes that long ago, a man named Aeneas and some of his friends escaped from the tire fire that was the Trojan War, went to Italy and becomes king of a land called Alba Longa. Some legends say that Rome would eventually be named after Roma, a woman who traveled with Aeneas. Upon landing on the Tiber, Roma and her ladies weren’t best pleased about moving on from what seemed like a perfectly good place to found a city. So her posse burned the Trojan’s ships, purposefully stranding them in the place that would become Rome. Much better!

A few generations later, two brothers had a fight over who had the right to rule it. The victorious brother, Amulius, killed his bro Numitor’s sons and exiled his daughter, Rhea Silvia. He made her become a Vestal Virgin, a priestess position we will talk about a lot more later, to ensure that she wouldn’t give birth to future rivals.

Maybe it’s just me, but this she-wolf looks like she might be regretting her life choices.

Romulus and Remus suckled by a long-suffering she-wolf.

But the gods sure love to stir the pot. So Mars, the god of war, comes down and rapes Rhea Silvia, and nine months later she gives birth to twins: Romulus and Remus. A warrior taking a woman against her will: not an origin story I’d be super excited about, but we’re going to see the whole thing play out again and again.

Feeling threatened by these teeny babes, but not wanting to piss off the god of war, Amulius imprisons Rhea Silvia and has the babies abandoned by the Tiber River. I mean, it’s not murder when you abandon kids and let the Fates decide if they live, is it? The twins are rescued by a she-wolf, who feeds and takes care of them until a shepherd named Faustulus finds and adopts them, raising them on what will one day become Rome’s Palatine Hill.

When they got older, they decided they didn’t want to rule old Alba Longa, anyway – boring – but found a city of their own. As twins will do, they fought over exactly where they should found it. Much shoving and petty insults later, Romulus killed Remus and named the new city after himself. Mmk.

To get his Roman party started, Romulus invited a colorful cast of characters to come and live in his new city: cutthroats, runaway slaves, former prisoners. Come on down! But there was a problem. None of them were going to produce any progeny without a lady or two in the mix. Where my ladies at? So he called up his neighbors, the Sabines:

ROMULUS: “Hey, guys, Rome here. Wanna send us over some of your women so we can fill our new city with strapping Roman youths?”

SABINES: “Nah, we’re good.”

ROMULUS: “Well screw you and your goat, then.”

ONE WEEK LATER…

ROMULUS: “Hey, guys, Rome again. Sorry about insulting your goat and all that. Want to come on over to this festival we’re throwing? We’re TOTALLY not interested in stealing your women during it. But we are very interested in getting you toasted.”

They get the Sabines drunk as skunks, then proceed to kidnap their wives and daughters. It’s kind of like the musical Seven Brides for Seven Brothers, but with a whole lot less singing.

Romulus then pressures these women to marry his men. Livy tells us that he gives a rousing speech promising: “…they should be joined in lawful wedlock, participate in all their possessions and civil privileges, and, than which nothing can be dearer to the human heart, in their common children.” Tempting, Romulus. Very tempting… But when the Sabine menfolk come back in a rage to battle the Romans for their women, they intervene, showcasing some serious Stockholm syndrome. “If you are dissatisfied with the affinity between you,” the ladies say, “if with our marriages, turn your resentment against us, we are the cause of war, we of wounds and of bloodshed to our husbands and parents. It were better that we perish than live widowed or fatherless without one or other of you.” In other words, please don’t fight. We’d rather die than cause trouble! Does this sound like a myth written by a man or what? But it does show us what matters to Romans: respect for the father and the gods, for one. For the other, the role women have to play as bridge builders: the link that holds society’s chain together and create peace between men. Even when it comes at their expense.

This is fine!

The Intervention of the Sabine Women, David, 1799, courtesy of the Louvre Museum

Wife-napping complete, Rome started to grow in earnest. For a while it was ruled by kings, all elected by the people, and the city developed into an up-and-coming urban center, quickly outpacing many of its rivals in the region. But by 509, the populace was growing tired of answering to royal overlords. And then a woman named Lucretia pushed them over the edge.

The story goes that she was sexually assaulted by a guy named Sextus Tarquinius, the son of the current king. Apparently one evening he had some friends over for drinks, one of whom was Lucretia’s husband Collatinus. A few bottles deep, they started debating whose wife was the best, and Collatinus insists that Lucretia would put them all to shame. So they rode around to each man’s house to see what their wives were doing. They found them all getting ready for a night on the town, but not Lucretia: she was weaving dutifully with her maids. Prince Sextus was so impressed by her modesty that he returned several nights later, when Collatinus was conveniently out of town, and asked if he could stay over. Being a good hostess, Lucretia said sure, here’s some food and a guest room, while probably also sighing internally with a “I wish he’d stop checking out my boobs already.” Later that night, Sextus crept past her sleeping servants into her bedroom and declared his passionate love for her. Yikes. But she refused to submit, until he said that if she didn’t he would kill her and lie her naked body next to one of her slaves so that everyone would think she died in the midst of adultery. Post assault, she bravely wrote to her husband and father to come at once, and told them all about it. She asked them to win vengeance for her. And though they tried to tell her that it wasn’t her fault, Livy tells us, she tells them:

“…though I acquit myself of the sin, I do not absolve myself from punishment; not in time to come shall ever unchaste woman live through the example of Lucretia.”

She grabs a knife and commits suicide rather than live with her honor tainted. Her raging male relatives carried her body into the street, stirring up the public’s anger, and they went after Sextus with everything they had. In doing so, they effectively killed Rome’s monarchy. One of the guys who accomplished this was named Lucius Junius Brutus: we’ll return to that name in a minute.

While she’s in era-inappropriate clothing, the action behind this painting still captures Lucretia’s horrible end.

Lucretia by Rembrandt van Rijn, 1664. Courtesy of the National Gallery of Art.

Though it’s entirely likely that she’s mythical, you could say that a woman helped birth the Roman Republic. Are we sensing a disturbingly violent trend here? Again, we learn a lot about how Romans think about women. First, that though everyone agreed the assault was not her fault, the shame and dishonor of it still stand squarely on her shoulders. Second, that a good woman is both fierce, demanding vengeance, and brave, able to take her own life, which she has to do because she can’t ever be that honorable woman again. Yikes. We also see how a woman’s fate has the power to change the course of history. Though often she’s not doing it by fighting, but by dying. Which is a somewhat depressing thought.

And so Rome is now a Republic, set up by a group of ancient aristocratic families known as the patricians. Never again will they suffer a king, they swear, and their aversion to royalty works its way down the generations. The people get to elect their own magistrates: men who make decisions on everyone’s behalf. They’re advised by the rich guys who make up the Senate, a government body that is chosen by the city’s wealthy and are made up of patricians. A senate position is for life, so they’re powerful, but they’re kept in check by two consuls. These guys are probably the most powerful in Rome, but they can only be consul for a year at a time. This system of checks and balances is a far cry from Greece’s absolute democracy, but it means that no one man has absolute power...for now. And women have little power at all.

The Republic kicks along for quite a while fairly happily, but unrest and inner strife start to break things apart. There are growing resentments between patricians and plebeians, the working class, that erupt into strikes and other trouble. And as the territory expands, we see great generals emerge who become very rich, very famous, and develop massively inflated egos, often with big and loyal armies at their backs. We see these generals start to change things. A guy named Marius ends up consul an unprecedented seven times; another guy named Sulla goes against him, sparking Rome’s first civil war, and eventually, with Rome in the middle of a war emergency, Sulla steps in and names himself a temporary dictator. Many heads are hung up in the Forum; things are getting ugly. But then they settle down again, and people assume the Republic will go on as before.

But no dice, because there were plenty of young men who looked up to Marius and Sulla and were like, “hey, they did it. Maybe I can too!” And so, along comes a guy named Julius Caesar. This fallen rich boy and military star does many fascinating things, some of which we’ll talk about when we explore the women who pass through his orbit: he recites poetry for pirates, he leads many military campaigns to surprising victories, he sleeps with many people’s wives. But one of the most bizarre and impressive things he did, with help from his fellow triumvirates Pompey and Crassus, was kick down the final straws of the Roman Republic and send it careening toward an empire with…not a KING, exactly…but a system where one man – and sometimes the woman next to him – ruled.

Caesar declares himself dictator…not just for now, but for LIFE. And then he starts acting a little too kingly a little too loudly, and the Senate starts sharpening their knives. One of those guys was a fellow named Brutus – remember that name? – who feels it’s his personal mission to make sure no king ever rules Rome again. And so in 44 BCE they stab him an outlandish number of times in the middle of the Forum. Look, everybody! No more kinging! But the people aren’t grateful: they are pissed.

The assassins run, and some new ambitious young men step in to chase them: Octavian, Caesar’s adopted son, his bro Marc Antony, and another guy named Lepidus. After battling the assassins, and then battling each other for who would be the champion of Rome, Octavian emerges victorious. And after almost 200 years of continual war and severed heads hung up around the city, everyone’s tired and just wants things to calm down.

Marc Antony's Oration at Caesar's Funeral by George Edward Robertson, 1864, Wikicommons

And that’s how Octavian takes the name Augustus and become Rome’s first emperor. Though he spends his whole life insisting that he ISN’T REALLY an emperor: “Don’t worry, guys, we’re still a Republic. Like, I’m not an absolute ruler. No: I’m just its Princeps (First Citizen), and the Senate still has lots of power. I just happen to be really smart and so everyone agrees with my decisions.” And everyone went yeah, fine, OK, let’s all pretend.

After he dies, we see many more emperors who are…less shy about claiming their power. Some are great, some just okay, some who are too busy cross-dressing and throwing giant ragers to govern effectively, and some who are just downright crazy. We’ll meet a few of them later, but if you want a full and very pretty-looking graphic that gives you a rundown, check out the Timeline of Roman Emperors that author Pamela Toler and I made just for you. You can peruse it on the show notes, or you can buy yourself the poster-sized version in my Etsy shop. It’s full of the influential women around the emperors, too, and some of the ones who oppose them. Naturally.

This timeline is a collaboration between Mr. Exploress, Pamela Toler and myself, and I’m loving it! It is now available to buy in my Etsy shop if you’d like it to hang up on your wall at A2 poster size. That’s really when it’s at its best.

Back to the Empire. Its real heyday stretches from 29 BCE to about 180 CE. Thanks to ambitious rulers and a truly killer military, at its peak the Empire has control of everything the Mediterranean touches: it gets so big that the empire has to split into two because it’s just too vast to be ruled from one city. But eventually, things start falling apart. Bad and short-lived emperors, plague, invasion, so much stabbing. By 476, the Western Empire has fallen. The Eastern Empire, and its capital city of Constantinople, will keep on thriving for quite a long time.

So now we know: there’s a period of kings, then the Republic, then the Empire, which eventually splits into two. I’ve obviously left out a whole lot of detail here; we’ll get a glimpse at several of these periods in much more detail as we move from one interesting lady to the next in our series. But since we’ve got to settle somewhere, let’s explore life as fairly fancy patrician matroni, or married women, at the height of the Empire, in the year 110 CE.

UP AND AT ‘EM

But before we roll out of bed and get going, we’ve got to sort out who exactly we are. What a lady’s average day looks like in Rome depends very much on their socio-economic status and, importantly, whether they are slave or free. If you’re foreign, even if you are free born, you have limited rights within the Empire. But if you’re a citizen of any station, you have some coveted rights: suffragium, or the right to vote; commercium, or the right to enter into legal contracts, and connubium, or the right to marry. We lady citizens, of course, most certainly aren’t entitled to all three.

If there are two things we Romans are obsessed with, it’s family and status. Our gens, or family clan, is everything: it dictates our name, our status, our place, our rights. It’s one of the most important things about us. Remember that. At the top of the power pyramid sits those ancient patrician families who started the Republic, including the emperor and his family. These wealthy upper classes are well connected and tend to hold most of the high political and religious positions. Then there are the equestrians, or knights, one rung below: you could say they’re the business class of ancient Rome. To be an eques, a man has to prove he holds property valued at 400,000 sesterces, while a senator has to prove he’s worth 1,000,000, so that paints a picture of the difference. Then there are the common folk, called plebeians, or plebs. Below that are freedmen and women: those who were once enslaved, but have found their way to freedom. Though considered low class, some freedmen become wealthy and influential. And then, below that, there are a whole lot of slaves.

It’s tough to move up the Roman power ladder, given that it’s based on your family name, but not impossible. Rome’s a city full of clients and patrons: people making deals and alliances, always seeking to improve their lot. Let’s say our family is fairly well to do, from good patrician stock. That being the case, our house, or domus, is likely to be on one of Rome’s seven hills: the higher up we are, the better off. It’s cleaner up on the hill, the view is better, and the smells from the teeming city below are less troublesome. We wake early – with the sun, as no electricity means to tend to work in time with the sun’s rise and fall. Roll over on what’s probably a mattress stuffed with straw, wool or even leaves, and let’s get going.

We’ll be waking on the second floor: the domain of women and servants. Enjoy the solitude, if you happen to have it, because in our very full house, privacy is going to be a hard thing to come by. The room we sleep in is called a cubiculum – yes, that sounds like “cubicle” for a reason, and that’s just about how small they are. Dark and cell-like, with no windows, it has room for sleeping and not much else. Our house is rather like a fortress: pretty from the outside, but built to block out the noisy, sometimes stinky world outside. So though you’re likely to have some pretty frescos on your walls, you can only admire them once your eyes have adjusted or if you’ve lit the lantern near your bed. The house is prone to drafts, too, so if it’s winter there might also be a brazier on the floor to keep you warm, so try not to trip over that.

Our first stop might just be the latrina, which is our at-home toilet. Most well-to-do houses will have them. Emperor Hadrian’s villa will feature 35 toilets, though the average home probably only has a few. It’s likely to be upstairs, or down near the kitchen, or out in the courtyard to try and deal with the smell. It’s likely to be a single-seat toilet, unlike in the public restrooms we’ll visit later, built into the wall and hopefully with a door to close behind us. Its seat is made of either wood or marble, and the hole is shaped something like a keyhole, just like our modern toilets. It’s likely to either be a cesspit toilet, or have a terra cotta drainpipe leading to a discreet downstairs location or perhaps even the street. To wipe, we might be using a sponge on a stick, which we will share with the other members of the household…no thank you! Or we might be using a hanky, or perhaps even just our hands, which we can always just wash off in a minute. That method sound gross to us, but is certainly the most environmentally effective. Who uses what toilet is probably tied to your status in the household; given our obsession with status, I can’t imagine we matrona are sharing a bathroom with the slave who does our hair, but I could certainly be wrong.

snuggle up, bathroom buddy!

Some ancient Roman toilets in modern-day France, courtesy of Jens Vermeersch on Flickr

Feel like hitting the shower? Well, that’s not happening. Though we Romans are fairly famous for our cleanliness, full bathing doesn’t often happen inside our homes. Bathtubs do exist in some rich houses, but they’re a rarity. At most, you might fill a basin with water and give your hands and face a rinse.

Is the water clean? Where does it come from? In this respect, we’re in luck, because we’ve perfected the art of water transport. Rome built its first mighty aqueduct back in 312 BCE, setting a precedent for water purity, control and extensive plumbing that won’t be matched again for millennia. You can see these structures from far outside the city, as iconic a sight as New York City’s skyline, carrying water from far afield into our streets and alleys. Though much of the 250-mile system is actually built underground. They are a really big ancient world deal. “All the abundant supply of water…” Pliny tells us, “…for public buildings, baths and gardens…coming from such a distance, tunneling through mountain, and levelling the route through deep valleys must make this the most remarkable achievement anywhere in the world.”

Relying on gravity to keep things moving, they usher water down waterproofed beds made of concrete, which is actually a Roman invention, though it’s not quite like the stuff we pour into sidewalks in our era. It’s created with volcanic ash, lime and seawater mixed in with volcanic rock. It’s more durable than the stuff we make: it even gets stronger over time. Specialized workers known as aquarii keep it clean, along with special tanks called piscinae limariae where impurities can be decanted. By the time the water collects at the end in a reservoir, where it is stored and then released into lead pipes that make it to most street corners, it’s shockingly clean for an era well before water purification plants.

Color me impressed.

The above-ground portion of an aqueduct in modern-day Spain, courtesy of seriykotik1970 on Flickr.

They’re carrying a lot of water: we’re talking 200 million gallons into the city every day, used for everything from drinking and cleaning to powering industrial water mills. Some industrious city residents even build their own illicit pipes, tapping into the public system to bring water directly into their homes and gardens.

And of course, it feeds our voracious love of public bathing. But going to the bath is an afternoon activity, and one we’ll need to leave the house for. So for now, let’s go ahead and get dressed.

TOGA PARTY

Rome is a place where what you wear can say a LOT about who you are and how people should treat you. Downstairs in his bedroom, your son will be stretching, rolling out of bed in the loin cloth and tunic he probably slept in, then having a slave help him get into his toga. This is the standard outfit for adult male citizens. He’ll have to think carefully about what that toga looks like, though, as our sumptuary laws dictate quite strictly who can wear what. Togas trimmed with purple are only for boys under sixteen, called a toga praetexta. But once he is initiated into the world of men, his toga will be white.

You will be sporting what is in some ways quite a similar outfit, though you wouldn’t be caught dead wearing a toga. You COULD, but then people might think you’re either a prostitute or an adulteress, which is probably not the look you’re going for. Another important thing to note: the more skin you’re showing, the less respectable people are going to find you, and the lower status they’ll assume you are. Only slave girls and women of the evening bear their ankles in public! Such things might cause public unrest.

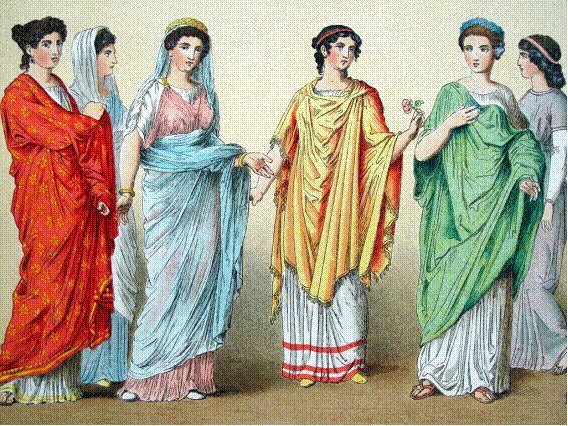

Let’s pause in the nude. Keep in mind that a lot of our knowledge about what women are wearing comes from statues and funeral reliefs, all carved by men. They serve as something akin to an Instagram feed: an artful idealization of what we want people to think we looked like, but not necessarily the best evidence for our actual day-to-day. Luckily, Dr. Rad and Dr. G are here to help.

So, first, let’s deal with our undies. Are we wearing any? The answer seems to be….maybe.

DR. RAD: “…it seems that there's not a lot of underwear like we would recognize it going on. There are images of people wearing what looks like modern underwear to us, but that's probably because they were people...who were engaged in some sort of physical activity, which meant that they couldn't wear what a Roman would normally wear….” Whatever underthings we’re wearing are called subligaculum, or “a little something underneath.”

While our son is probably wearing either nothing under all of his layers or something akin to a loincloth, it’s possible that our underwear is a bit more elegant, probably made of linen imported from Egypt. But here’s as fun fact: we might ALSO be wearing the equivalent of some leather bikini briefs.

DR. RAD: “There is potentially some evidence that women might have worn at some point some sort of like leather bikini. Like maybe when they had their period or something or if they were working out, but it's very speculative on that.” They seem to be made out of goatskin: not very breathable, I would imagine, but definitely waterproof. So if it’s your time of the month, make sure to keep an eye out.

We’ll have a bra too, called a strophium, which is there to bind and lift up our lady orbs.

DR. G and DR. RAD: …women would wear like a sort of breast-band. And it seems like a respectable woman would keep that on even when she was having sex. And this could be used for like a number of reasons.

Our friend Ovid, who seems keen to give ladies advice about how to look their sexiest, tells us that if our breasts aren’t quite the right shape, we can always stuff these bras. Dr. Rad and Dr. G concur: it’s versatile.

DR. G and DR. RAD: …it seems that this could be worn a number of different ways, kind of like there are different kinds of bras, in that women could potentially wear them to pad themselves out like a padded bra. So if you wanted to make yourself look bigger than you actually were, you could potentially wrap around more fabric so that your boobs appeared bigger than they were. Or you could potentially wrap in a certain way to maybe provide a bit more emphasis or, you know, a bit more of a cleavagy look potentially. It also goes the other way, in that you could potentially wear your breastband so that your boobs are minimized or strapped down essentially.

But are all women wearing these wraparound bras? We matroni probably are: in fact, we have written evidence that we don’t take them off during sex, much to the frustration of our husbands. Because

Dr. RAD: ...it would be tricky to take off quickly. We do have sources that say that prostitutes could suddenly flash passerbys and show their breasts. So that would imply that they're not wearing it. But having said that, again, we do have images in art in places like Pompeii, for example, where women are shown having sex and some of them are wearing it and some of them aren't. It's a bit unclear exactly who was wearing it, but presumably respectable women would be wearing one, and we do have references to like slave girls wearing one. So it seems that, yeah, a lot of women probably would've been wearing like a breastband of some kind.

The body ideal we’re shooting for is thin, but with hips wide enough to suggest our potential success at childbearing. But we respectable matronai are not wandering the streets showing off skin or cleavage. Layers are most definitely the name of the game.

See the following video to get a good visual sense of Roman dress conventions for men and women:

We’re probably putting on some kind of slip.

DR. RAD: …something called a supurus, like an under tunic. So it's something that was maybe like a short...I guess kind of like we might think like a short nightie, or a short little dress or something like that that you would potentially wear. Again, it's not really clear how many women would have been wearing one of these. And there's some suggestion that maybe it was something that just young girls wore, but then we do have these references to adult women wearing them, too.

And this is just one layer of several, which if Roman poet Martial has anything to say about it, is going to cause us some distress: “Your unhappy garments, Lesbia, treat you indecently. When you attempt with your right hand, attempt with your left, to pluck them away, you wrench them out with tears and groans, they are so gripped by the straights of your mighty rump.” So, yes: once we’re fully dressed, picking that wedgie is going to be a laborious process.

One thing we will definitely all be wearing is a tunic.

DR. RAD AND DR. G: So the tunic is like your staple garment that everyone would have worn. And the main differences as far as women were concerned probably would have come from like what status you were….So you, basically if you were an elite woman, you probably would have been wearing a tunic that would go all the way down to your feet and provide basically coverage because you're a respectable Roman woman. How stifling! Exactly. No showing off those ankles!

After that, since we are fancy ladies, we will pull on our stola, which goes all the way down to our feet. In fact, it might be longer, so we’ll need to pull it up around the belt we will soon be wearing, kind of like you would a loosely tucked-in t-shirt.

DR. RAD: This is basically like the female equivalent of the toga in that it's something you would wear to show off your status as a citizen: a Roman married woman.

Despite what you’ve seen in period films, your arms and cleavage are not likely to be on display here: the top edges of your stola will probably cover your upper arms, either stitched at the shoulders or pinned all along to show only teeny peeps of skin. That might change if we’re of a lower station: slave women usually have their tunic fall just above their knees, as it’s more practical for their duties. And as a helpful bonus, this helps us know at a glance who is who and how we should treat them. When it comes to our clothes, class is everything.

Dr. RAD and Dr. G: …this is something that the Romans are sort of constantly wrestling with. They have what seems to be a fairly clear dress code so that you can tell who someone is in terms of their social standing just by looking at them. But that starts to get muddy very quickly, because, of course, if you're an upper-class person, do you want your attendants who are slaves to be walking around in rags? Probably not. You probably want them to be dressed reasonably nicely, too. And we do have records of this. And there's definitely always anxiety about can you really tell who's who? Like what if a slave girl got dressed up in upper class clothing: could you tell that she was actually a slave?...Oh, the horror of it all! You couldn't tell on site exactly who somebody was. You couldn't tell if they are a lower class. Bleh!

We might belt our stola under our breasts to create artful folds, then cinch it in with a thicker belt at our waist. The look we’re going for is svelte, but with hips that suggest superior childbearing. Though it’s likely we’re going to be so wrapped up in our next garment that I’m not sure how many admiring men on the street might notice. It’s worth noting here that by the era we’re walking in, there’s evidence to suggest women are no longer wearing this iconic piece of clothing, but just a tunic. Which makes sense, given the weather conditions.

Dr. G: You think about the Italian summer. It's hot, it's sweaty. You're thinking about having a drink, but instead you're wrapped up in a whole bundle of fabric like some sort of weird cocoon.

Later, when we go out of the house, we’ll wrap ourselves in our palla: a two-meter wide, six-meter long scarf and cloak combo that will hang in heavy folds and cover up much of our bodies. There are tons of ways to put it on, but we might need some help from a servant to do it.

DR. RAD: …as Dr. G and I can both attest because we've tried this at ourselves, it's a huge amount of fabric.

DR. G: Yes. The palla is gigantic.

DR. RAD: It's really hard to actually do anything while you're wearing it.

DR. G: It's quite constrictive.

all wrapped up. it’s hot in here!

Roman matrons and the colorful garments, Wikicommons

Sometimes the end will be thrown over our left shoulders, with the end dangling down in front, and the other end drawn around the back and brought around. Likely you’ll need to carry at least one end in your arms, don’t plan on dancing a jig or doing any calisthenics.

DR. RAD: I think that's part of the important thing about the stola and the palla is that they are uncomfortable and unwieldy garments. So in a way, they become a real visual signifier for the upper class. Because who can afford to not have a fully functioning body when they're out in public? And it's really only the elites who, one had the capacity to show off that they can possess such fabric. But also to just be so uncomfortable and do not really have to do much, just sort of parade around and have a particular appearance in the public space.

It’s so big that we can even cover our heads with it: some sources say that married women ALWAYS cover their heads in public, but we don’t know if that’s actually true. So I’ll leave that decision up to you.

Our clothing is probably made of either linen or wool, though they could be cotton. If we’re feeling fancy and have the money to afford it they might also be silk brought all the way from Asia. You’ll want to be careful, though, because Romans have some serious anxieties about seeming either too loose or too excessive when it comes to our outfits.

DR. RAD: …there's always this sort of a moral conversation in the Roman texts about what people in general are wearing, but particularly women. There's always a fine line between appearing, you know, refined and civilized and showing off your status and going too far and being too luxurious. The Romans lose their minds over this kind of stuff all the time with both men and women, but particularly women.

Our pallas are likely to be colorful, too. While statues of old probably have you picturing our getups as all white and sheet-like, we Roman ladies LOVE color. In fact, ancient world Greek and Roman statues weren’t originally white at all, but painted quite brightly: that whole minimalist chic thing we associate with this time period is just a product of paint fading over time. Our dyes are made from plant-based material, and it’s expensive, so most people are wearing black, brown, grey, and cream. Hot tip: do not wrap yourself head to toe in purple, as that’s the emperor’s color and you’re going to get in trouble if you choose to flounce around in it. Anyway, it’s royally hard to come by: Pliny the Elder says it’s made from the murex mollusk and that it takes 10,000 of the shellfish to make just one gram of dye. A pound of nice purple silk will run you 100,000 denarii, which will also buy you half a dozen slaves or a pet lion. So… Red is also considered a power color, made from crushed roots or bugs, whereas white is used for ceremonies and holidays. How do we keep our woolen whites so white, you wonder? We have people called fullers to launder them for us. They use uric acid to keep our woolen garments looking good. There’s nothing quite like the smell of pee-starched tunics in the morning.

Though these decisions may seem trivial, they’re anything but. In a world where women can’t vote, and in fact only have so much power in the public sphere, what they wear really matters, both as an expression of their social situation and status. It can tell viewers how important they are and if they’re married. It’s one of the clearest modes of expression women have. And we aren’t about to give it up. Back in 215 BCE, the city’s rulers passed a wartime austerity measure called the Lex Oppia: a sumptuary law aimed at curbing what women could wear and do in public. After the wars end and there are noises about keeping this law in place, women from inside and outside the city storm the Forum, taking the streets and intimidating voting men into submission. We’ll dive into this moment more in a future episode, but suffice it to say that dress matters.

Now that we’re dressed, it’s time for hair and makeup. Downstairs in his chambers, your husband is probably going through a series of his own beauty rituals: since Alexander the Great set the trend for going beardless, he has to get the dreaded beard shave, done by a servant or slave, and then have that servant pluck his eyebrows and any stray neck hairs. So we can comfort ourselves that we aren’t the only ones suffering for beauty. Suetonius tells us that Augustus, Rome’s first emperor, was known to depilate his leg-hairs by rubbing them with scalding-hot walnut shells. Dang, Augustus! Not that we’re exempt from this torturous plucking game. The poet Ovid, in his book The Art of Love, mentions how important it is to deal with our “underarm goat and bristling, hairy legs” if we want to be considered fine ladies. Thanks, Ovid! We’ll get RIGHT onto that, but first let’s deal with skincare. Hang on tight, because this might take a while. It’s worth noting here that this beauty regime is probably only enjoyed by the very upper classes, as they’re the ones with the time and money to afford them. It’s also worth keeping in mind that a lot of our information about said beauty rituals comes from the writings of men, some of which are meant to be satirical and are often meant to be judgmental.

i find the graphics a little creepy on this one, but it’s a great visual overview of the kinds of our ancient Roman beauty rituals:

In terms of skincare, we feel quite strongly about it. Roman women feel a lot of pressure to have smooth, unblemished skin: a sign of health, of good living, and of general sexiness. In the ancient world, which is full of barely-treatable diseases, this has got to be a difficult thing to achieve. Pliny the Elder mentions a whole host of potential skin problems we might have to deal with: pimples, freckles, spots, facial itching, eruptive skin diseases, leprous sores, and scars, to name a few. Luckily we have a wide array of both mundane and bizarre skin concoctions for treating them.

Some of the ingredients we’re slathering on are ones the modern-day lady will have no problem getting down with: olive and almond oil, honey, fruit juice, seeds, mushrooms, poppy seeds, rosewater, and many forms of fat, both plant and animal. Others are…a little more adventurous. For example, cow placenta is supposed to be great for curing skin ulcers. Bull bile stains the face a pleasing hue. For wrinkles there is swan's fat, asses' milk, or axle-grease. For freckles there is ash of snails. Overnight, we may even have slept in a face mask made of grease derived from unwashed sheep’s wool, which Ovid complains will “offend all noses.” And this is only a partial list.

One of our primary objectives is to look as pale as possible. Tan skin is a sign of the working class, and as patrician ladies we wouldn’t want to be confused with one of them. We have many lotions and creams to help us with this. Narcissus bulb, cantaloupe root and cumin are all handy whiteners, and probably aren’t going to corrupt our organs. Archeologists have found evidence of facial creams containing animal fat, starch and lead or tin oxide, which when rubbed on will leave a smooth, powdery texture and make the skin appear paler. Lead is GREAT for luminous skin: just ask Elizabeth the First! Too bad it builds up in your system, doing all sorts of nefarious things. We might also use white marl, a type of clay, or chalk dust to achieve this aim. Later we might even bathe in asses milk—rumor has it that Cleopatra was a fan, and it’s supposed to help make us pasty as hell. And then of course there’s that old Egyptian staple, crocodile dung. Galen says that it is highly prized. “…it is not enough that there are countless other cosmetics by which their faces are made smooth and shiny,” he says. “No, they also include the dung of crocodiles.” Pliny the Elder assures us that it comes from crocs who live on sweet-smelling flowers, so it actually smells quite pleasant. Spoken like a man who’s never smeared feces onto his face. It’s quite possible that men like Pliny were exaggerating on this point, saying that we slather ourselves in excrement as a kind of pot shot at women who go to extreme measures to be beautiful. Or it could be that we are actually willing to go to such lengths because of the age we live in: it’s unclear.

For those moments where face creams and makeup just won’t do it, we have other means of covering up our skin’s imperfections. Namely, little patches called alutae or splenia. These teeny leather scraps are sometimes treated with alum, then pasted directly on the skin as a kind of artful beauty mark. We might even cut them into cute little shapes and turn them into a fashion statement, much like we’ll see again in 16th-century France.

We also want our teeth looking pearly. Black teeth are something we see frequently amongst slaves and the lower classes. As Ovid tells us, if you’ve got discolored teeth you’ll have to laugh with your lips firmly closed. “You can do yourself untold damage when you laugh if your teeth are black, too long or irregular.” We’ll use things like natron, a kind of bicarb soda like the Egyptians use, and rinses to try and keep them looking bright. We might also give them a little rinse with urine. I tell you, it’s so versatile!

When it comes to body hair, Ovid’s right: we want to keep everything below our eyebrows to a minimum. Several ancient writers suggest that we take much of our body hair off. Much like the Greeks, we’ll be shaving, plucking, ripping it out with resin paste, or scraping it off with a pumice stone. Though we have graffiti from Pompeii that suggests some men advocate for a bushy below-stairs carpet [“It is much better to fuck a hairy cunt than a smooth one: it both retains the warmth and stimulates the organ” (oh my)] – some women are removing some or all of their feminine shag rug, as we discussed in our episode on pubic hair removal through the ages. That should be fun, but nothing the time traveling woman hasn’t had a run-in with before. Also like the ancient Greeks, Roman ladies are said to strive for a fuller eyebrow. A writer named Claudian praises a woman’s beauty by saying: "[W]ith how fine a space between do your delicate eyebrows meet on your forehead." We’ll be darkening and extending them with makeup to make sure they’re as close to a unibrow as possible.

And now our slaves are pulling jars and bottles out of a wooden beauty case, getting ready to make us up in ways we’re very familiar with today: we’re having our eyelashes tinted with ash to make them look fuller. Unmarried daughters especially want to ensure their eyelashes are present and accounted for because, as Pliny the Elder writes, “the eye-lashes fall off with those persons who are too much given to venereal pleasures.” Eyelashes accentuate your chastity, ladies!

To further enhance our eyes, there is kohl, like the Egyptians use, which we will mix with some oil or fat and paint on with a brush. But we can also avail ourselves of squid ink, antimony, and something called lamp-black, sometimes mixed with saffron to help mitigate the smell. Eyeshadow might contain charred, ground rose petals, roasted date stones, or a paste made from toasted ants. Sticky! We’ll also paint on some rouge to give our cheeks a healthy glow. We have several to choose from: made of red ochre, rose and poppy petals, or red chalk.

Some of these ingredients aren’t the best smelling, so we are very keen on perfumes. And while we Romans certainly didn’t invent personal fragrance, we did inspire the word perfume, which comes from the Latin per fumum (which means ‘through smoke’). Remember that we haven’t learned yet how to distill alcohol, so to make them we take olive oil and add in some nice-smelling plants and woods to steep. We’re big fans of many of the same scents as the Egyptians; one rough guesstimate says that by 100 CE we’re using some 2,800 tons of frankincense a year. We sprinkle it on bathroom walls, put it on the soles of our feet, add it to baths, anoint military standards. Some sources whisper that Emperor Nero, who we’ll meet in a later episode, loved the smell of roses so much that had had silver pipes installed so his guests could mist themselves with rosewater. Pliny tells us that we even put perfume in our drinks. He also says that Romans waste “…a hundred million secterces every year; that is the sum which our luxuries and our women cost us …” Blaming it on the ladies, as always, Pliny. I’ll bet that guy is a barrel of laughs at a party.

It always pays to smell one’s best.

Roman perfume bottles (unguentari) on display at Villa Boscoreale, Wikicommons

This seems like a lot. But if we’re in the privileged position to afford such beauty rituals, we can’t really afford to ignore them. Our makeup, we believe, makes us look healthier, younger, more attractive. The word for such things, medicamen or medicamentum, can mean cosmetic, poison, and remedy: these products aren’t used solely for the purpose of looking glam. But remember: restraint is key. We don’t want to be too heavy-handed. Wearing too much makeup can give others the impression that we’re cheap, vain, or a woman for hire. And so we see an age-old contradiction: men want you to look pretty and healthy, darling, but they don’t want you to look like you tried too hard. And they certainly don’t want to see how you do it. As the ever-lovely Ovid says: “…women should keep, till the work’s perfected, out of sight. Do I have to know why your complexion’s white? Shut the boudoir door—why show a half-finished painting? Men don’t need to know too much; most of what you do would shock us if it weren’t concealed from view.” Here comes another piece of advice from Lucretius, who says we ought to be “at greater pains to hide all that is behind the scenes of life.” If that doesn’t define the Roman woman’s lived experience, then I don’t know what does.

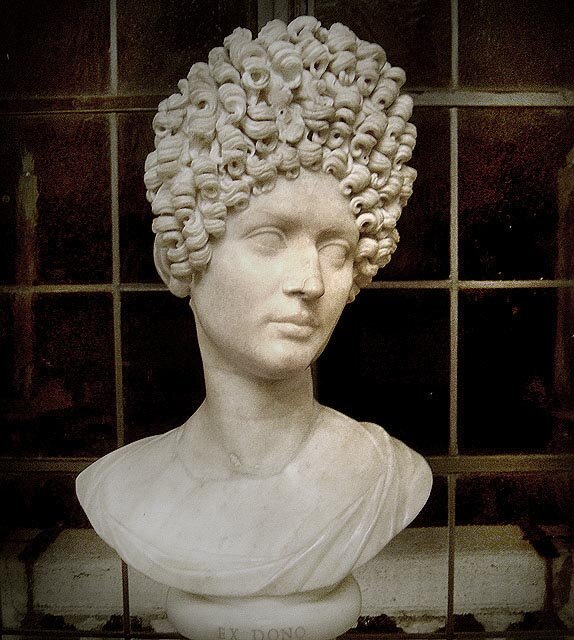

Now for hair. Tell us, Dr. Rad.

DR. RAD: Ancient Roman women don't seem to have been big on hats. What they do seem to have been big on is hairdos: really complicated hairdos, piled as high as the sky, sometimes: it's just curls as far as the eye can see…there's definitely certain kinds of hair styles that are on trend at any one given time, but they're all fairly complicated and probably would not have taken the weight of a hat. And they would often be built up with like various false pieces as well to extend the height of them. Yeah, extensions are not a new thing.

What style you’re sporting changes depending on who the empress is: she and her visible public statues are usually the ones that set the fashionable trend. Earlier, under Augustus’s wife Livia, we have a deceptively simple-looking style: wavy hair around the temples, a curl near the forehead and a bun low at the back, called a nodus. But by our current period, our Empress is a lively lady named Pompeia Plotina, and she’s totally a fan of vertically-inclined confections like the women of Flavian Dynasty that came before her. If you look at statues of our current empress, you’ll see that she’s a big fan of the 80’s-style poof of hair in the front, as well as a fetching headband which probably helps the style hold together. I wonder if she’s got some kind of Bump-it situation going on under there? We want our coiffure with many layers. Think of a wedding cake, but made of hair. As Juvenal has it, “So important is the business of beautification; so numerous are the tiers and storeys piled one upon another on her head!”

It’s likely we’ve got curls galore. Our servants will create them with a calamistrum, or curling iron, which is placed in the fire before being applied to our tresses. We’re placing a whole lot of trust in our female slaves. Hair dressing is considered so important that we even have a designated hairdresser, called an ornatrix, whose job it is to become an updo expert.

We might also dye our natural hair. Different kinds of animal fat, antimony, ashes, henna, or special soap balls to dye your hair black, red, or even blonde, if you’re feeling particularly bold. It seems to be quite a popular color, giving its wearer and exotic air, but I’ve read suggestions that the color is one that prostitutes often wear to distinguish them from fine ladies. There’s evidence that some women even dye their hair blue, but this is also apparently a sex worker’s color. Some women get to have all the fun…

It’s likely that you will also attach mountains of fake hair that’s going to piss everyone off at the theater. In fact, later this evening, we might wear a wig: around this time they’re very fashionable. I wonder if the Egyptians helped inspire this trend? We might have several to choose from: black, blond, or red, all made from natural hair. If it’s from a nation or people that Rome has conquered, all the better! Sigh.

Now for jewelry. It’s very likely we’ll be wearing some: fibula, or a kind of pin that keeps our clothing in place and which can act as quite a beautiful piece of jewelry in itself, necklaces, earrings, bracelets. We’ll see gold and silver, gemstones and exquisite detailing. Of course, much like with everything about our outfits, we’ll be very conscious not to overdo it. We respectable matrons have to think carefully about how garish our outfits are, as most Romans are suspicious of excess, and seeing it displayed by a woman makes them especially uncomfortable. What we wear and how we wear it matters, from the rogue on our cheeks to the shoes on our feet, because they say a lot about us and define how others see us. As a woman, this is an especially potent signifier.

What shoes we wear will depend on who we are and what we’re doing. While inside, we’re probably wearing a slipper or your iconic strappy leather sandals. But for outdoor use, we’ve got an array of others to choose from: we’ve got more slippers; we also might have close-toe shoes and half boots made of rawhide. Some of these are quite beautiful. I have a picture of an old Roman shoe in the show notes that has exquisite cutout designs on it that make it into something that most of us would be happy to wear in our century:

great design lasts the ages.

A Roman shoes, courtesy of Mictlantecuhtli via reddit

PART 2

Last episode, we learned a bit about our empire’s history, went to the ladies room, got ourselves dressed, done up, and ready for the day.

Now let’s descend the stairs and explore our house, or domus. The vast majority of Romans live in apartment blocks called insulae, which we’ll walk by a little later, but we’re lucky to live in something a little more luxe. Our house is fashioned like a Greek home, built around a central, rectangular atrium that is open to the sky. This pretty, open space lets light in, but also rain that filters through a bunch of terracotta pots and figures along the funnel-like roofline and tumbles down into a central pool. When it pours, it’s going to be hard to hear yourself think. The water goes down into a cistern, which will be your water source for most of your daily needs. It’s smart design and it looks pretty, too.

Our house is quite sparse in terms of decoration: as a rule, no lavish furniture here. The walls and floors, though, give us plenty to look at. They are covered in colorful murals and frescoes; we Romans do not approve of fresh white walls.

I hope you aren’t yearning for quiet time alone in your new home, because Roman domestic life is most certainly shared. You’ll be dealing with your kids, guests, probably extended family members. And like it or not, as a wealthy matrona, you are assuredly going to be dealing with slaves. They are a prevalent feature of life here and are, alas, something we cannot avoid. Slavery here isn’t race-based: life here is defined by social status rather than ethnicity or skin color, and if you’re a slave you’re at the absolute bottom of the totem pole. Many come from places Rome has conquered, sold into slavery after their side lost. Some are stolen and sold by pirates. Others come from within Rome itself, forced to sell themselves into slavery because they can’t pay their debts. Most are born free, and we Romans are very aware that it is an unfortunate state that can befall almost anyone. That doesn’t always mean they are treated kindly.

There are a LOT of slaves in Rome. By the first century BCE, they make up about 20 percent of Italy’s population. The good news is that they can be very influential in their households if they earn their family’s faith and trust. Some are eventually freed, and for those whose family or sponsors who are citizens, they can adopt the same status. Others are less fortunate, sold into hard labor, prostitution, to fight as gladiators, or are shipped out to large country estates where the work is pretty grueling. When it comes to how they’re treated, it’s a family affair: the law doesn’t much intervene. Your husband gets to decide how to treat those subjugated under their roof, and so do you. This is an ugly reality, but in a pre-industrial age slaves are quite literally keeping this Empire running. So make sure you’re extra nice to the women cleaning and cooking around you…and tell your son he’s not allowed to sleep with any.

KEEPING IT IN THE PATERFAMILIAS

As the materfamilias, or head woman of the family, you are in charge of managing the household. We will oversee the education of our children, plan dinners, preserve our house’s honor, and generally share whatever respect our husband has. You have power within these walls, make no mistake. But your paterfamilias has more power than you ever will.

In ancient Rome, our paterfamilias is very much in charge of us. Here’s Dr. Evans to tell us why.

Dr. EVANS: The paterfamilias is really...he's almost a God in the household. So something that I tell my students often is that Rome is the most patriarchal society I can think of, not because it's the most heavy handed against women, but because patriarchal literally means "the rule of the father." And for the Romans, the father was the leading figure in any household.” And that household isn’t confined to some nuclear family. “… he will usually be the oldest man of a maybe quite extended family. And there might be adopted children, there might be nieces and nephews whose father have died. So it might be more than just his children and his wife that he is literally the ruler of.

He's also the priest of the household, which means he carries out any rituals that need to be done at home. He’ll just pull up the hood of his toga and boom: instant priest!

He manages the money, strikes deals, and decides whom his children should marry. Rome’s first real legal code, the Law of the Twelve Tables from 450 BCE, puts women directly under the control of their paterfamilias. Because really, we’re too feeble minded to stand legally on our own! “Women, even though they are of full age, because of their levity of mind shall be under [male] guardianship.” That’s our problem, ladies: levity, which Merriam Webster defines as “excessive or unseemly frivolity” or “a lack of steadiness.” Thanks a lot, ancient men friends. Of course, not everyone agrees. A guy named Gaius said that “There seems…to have been no very worthwhile reason why women who have reached the age of maturity should be in guardianship. For the argument which is commonly believed, that because they are scatterbrained they are frequently subject to deception and that it was proper for them to be under guardians’ authority, seems to be specious rather than true.” Someone get that gentleman a drink!

The truth is that any of his children, either male or female, are under his authority, and technically need his permission to do pretty much anything. And that control means our father can do what he wants: whip, starve or exile us, if he so chooses, and while social expectation might intervene, the law isn’t going to. Who runs the world? Dad…sigh.

There is no worse crime in Rome than killing your father. The punishment is that you’ll be thrown into a sack with a dog, a cock, a viper and an ape, beaten and then thrown into the Tiber. A very unhappy sack indeed.

But wait…what about our husband? What’s his role in all this? There was a time, early on in Rome’s history, when our father transferred power over us to our husbands.

Here’s Dr. Evans again: It seems to have still existed maybe in the mid Republic, so we might be talking third century BCE, and then it might have existed in exceptional circumstances. And what the manus marriage means is that basically her husband becomes like her father to her. And the manus part of it, which means “hand,” is that she's given over to the kind of symbolic power of the hand of her husband.

But by the mid to late Republic, and definitely by the time we get into Empire, that sort of marriage seems really rare. So it’s dad who runs the show, and this remains true for as long as he lives. If you want a divorce – a thing that isn’t hard to come by in ancient Rome, with very few religious or social repercussions – you’re going to have to ask dad for permission. Doesn’t matter if you’re thirty and an independent woman, dammit.

This has its potential pros and cons, and a lot of them will depend on what kind of father we happen to have. For instance, if your marriage isn’t going well, you have a place to go: a financial and filial security blanket.

DR. EVANS: …I think that's probably better for women because I…and maybe I just think that fathers would be kinder to daughters, which is certainly not always the case… but if a marriage is bad, the father could drag her back into his family, as it were; maybe not drag, but accept her back into his household and he could then arrange a better marriage for her.

But it can also be bad, as dad can yank us out of our marriage anytime he pleases and launch us at another man if he thinks it’ll be more advantageous.

Dr. EVANS: Certainly the father...he still has the right over her dowry. So, for example, divorce is very common in Roman society, especially amongst Roman elites. So you're quite right that a father from an elite family might well decide, I need to make an alliance with that family now, my daughter is to get divorced and I'm going to marry her off to one of those sons. And as we'll see, technically, she has to give acquiescence to any marriage. But again, you know, how much freedom she actually had in that will depend on individual families and there could be a lot of pressure put on her. Similarly, the husband can just decide that he wants to divorce her and then she will go back to her father's household, probably. So it's like she never completely breaks away from her father's household.

Alternatively, if you’re widowed and want to marry again, dad has the power to prevent you. Famously, a tired and lonely Agrippina the Elder has to ask her much-loathed paterfamilias, the emperor Tiberius, if she can marry again. And because he sees her as a threat to his power, he says no, and there’s nothing she can do about it. But here’s a potential plus.

DR. EVANS: So if the paterfamilias, who might well be their father, dies, they might possibly be under their own law, as it's called: sui uris. So they might not be under the authority of their husband or their husband's father or the man in that family. So it is more complicated than just women are transferred around, although they are, and that the paterfamilias rules everybody in the household. Women are in a way in a sort of anomalous position in the household.

And there’s a series of laws that come into play during the reign of our first emperor, Augustus, that says that women who have at least three surviving children (and, if you’re of a lower class, four), you can be legally emancipated from father or husband. A baby bonus, as it were.

As Dr. Evans says: …that meant she could conduct business under her own name. And the Romans are obsessed with legal business. They're obsessed with wills…she could do all of that and buy and sell, which Roman women, if they had property, they could kind of do anyway. But technically, it was always under guardianship. So they had somebody called a tutaila, a guardian, who technically had to kind of approve any exchange of property. It might be another one of those categories whereby (pretty unlikely the tutaila would step in) but if you have obtained your legal freedom, you don't have to worry about it.

We’ll talk about that law and what it meant for women a lot more in another episode. For now, suffice it to say that while there are avenues to legal emancipation for women, the paterfamilias has the power to make it tough for us to operate independently. Though as we’ll see, these rules are probably somewhat subjective, and very much dependent on the kind of tutaila you have.

Here’s Dr. G: So if you've got a good tutor on your side, that you should get anything done. So everything about your potential to do business as an elite Roman woman is constructed through the lens of the male relationship. Yes. And if you happen to have a good setup, "good" in inverted commas, you have as much freedom as just about anybody else.

MEETING MARIUS

But all this talk of the patriarchy is wearying. Let’s fortify ourselves with some food. Our breakfast, or inetaculum, will feature certain staples: bread, buns, honey and milk. There might be some fruit, cheese, even meat, but no coffee or tea I’m afraid. If you’re anything like me, that caffeine headache you’re certain to get is something you’ll just have to suffer through. This isn’t a major meal, and will be eaten swiftly, as business starts early.

Speaking of business, let’s join another of the most important men in our lives: our husband Marius. Now that he’s had his leg hairs rubbed into submission, he’s ready to start conducting what’s called the morning salutatio.

Friendship in Rome is complex. Favors are the main social currency, and it’s all a complex game of who owes who. Later on, Marius might spend some of his morning going around visiting other people’s houses—his patrons, so to speak—offering support and asking for favors. But since he’s quite a big deal, most of the morning you’ll see his clients will show up at yours looking for an in with your husband, to ask his advice, strike deals or maybe kiss up. Rome is a world where who you know matters, and these webs of patronage are the oil that keeps the Roman machine grinding along. In short, husband dear is looking to grease wheels and keep himself well connected. His, and your, prosperity might depend on it.

The first thing guests will see when they walk into your house is the vestibulum, a kind of mud room. In a really nice home it’ll be a greeting space as well, laid out with fine mosaics that say things like ‘Greetings’ and ‘Beware of Dog.’ Marius may even have some death masks of his forebears hung up in this space, as we’re obsessed with our lineage, and maybe because nothing intimidates a visitor like a mask of a dead relative’s face?

As we watch Marius strut around in his toga, let’s reminisce a bit about our Roman childhood and what led us here in the first place. We’re lucky we made it to adulthood at all. The ancient world is rough on infants and mothers, and we think that something like 50 percent of Romans die by the age of five. As a girl, we were probably educated alongside our brothers, learning how to read and write. As fancy ladies, we may even have had a private tutor to teach us some Greek—which is, in our eyes, the height of sophistication. This is the great news about being an ancient Roman woman: education isn’t considered unattractive. Quite the opposite. In his Dissertations, first-century BCE philosopher and jurist Gaius Musonius Rufus said there’s no reason why women shouldn’t receive the same education as men: “Trainers of horses and of dogs make no distinction between male and female in their training.” Not the analogy I would have gone for, Gaius, but I’m feeling your point nonetheless. When asked whether women should study philosophy, he said, “Women have received from the gods the same ability to reason as men…It is not men alone who possess eagerness and a natural inclination towards virtue, but women…Women are pleased no less than men by noble and just deeds.” Preach, Gaius! Families with a reputation for an academic bent may even encourage their daughters to become intellectuals. But all this education isn’t to help us get a job or anything. It’s to make sure we can effectively manage our household, and because we play a major role in our children’s education. As Dr. Evans says, “They might not get exactly the same kind of education as men. They're not being trained for the courts and in the republic for political life. So they're probably not as trained in oratory. But we do know that there were female orators. We know their names. So they were able to do it. Some of them engaged in philosophy.” Though some men think that TOO much education might make us pretentious, or even worse, look sexually promiscuous. Are we just well read or a woman of the evening? It really is SUCH a fine line.

WIFING UP

You and your brothers would have played games together, with dolls, marbles, and perhaps with wooden horses on wheels. You would have worn clothes that clearly marked you out as children, including big amulets around your necks meant to protect you from evil and let other people know that, legally and otherwise, you aren’t yet legal. Romans might be marrying young by our standards, but they draw a distinct line between child and adult.

You weren’t left to this childhood for long. Growing up, one thing you knew for sure is that you were ALWAYS destined to get married. Marriage is considered a citizen’s right: it doesn’t apply to slaves, actors, or gladiators. And it’s crucial, because our primary role as Roman women is to have children and raise them up to be good citizens. Nothing matters more than that. Anyway, it’s not like you could have just moved out and become a career girl instead—not really an option for someone of our status—or hang around dad’s house being a drain on his financial resources. Not when we’re the glue that can adhere families together so nicely. In the Roman game of patrons and palm greasing, we ladies are one of our father’s most powerful bargaining chips.

For Roman elites particularly, who are the people we know the most about, marriage is NOT about love or a woman’s choice. It’s about creating alliances. As the paterfamilias, your father had the right to give you away to ANY man he saw as an advantageous match for the family. And given how young we are when we marry, it’s quite possible that we’ll have to marry several men during our lifetimes, and not always of our choosing. So get ready for some serious emotional whiplash.

You would have been married quite young, by our modern standards: probably in your teens, as young as 12 to 14, though your average marriage probably happened closer to 17 or 18. What is an ideal wife supposed to look like, you wonder? What was Marius looking out for? Well, loyalty is important. As is restraint, obedience, childbearing hips, and virginity.

All our young lives, our mother would have hammered home the importance of holding onto our chastity – or pudicitia– which is THE most important quality you can bring with you into the marriage market. Your husband is extremely unlikely to be able to say the same.

DR. EVANS: Pudicitia, chastity, is very important, reputation wise for an elite woman. It's kind of everything. So she's either a virgin or she's been married before and maintained chastity within that marriage, at least as far as anyone knows.

The great ancient writers, as we’ve already discovered, also love a woman who is ready to sacrifice herself for the greater good. Take the story of Aria. When her husband is ordered to commit suicide by the emperor, he hesitates…as one might. So she takes the knife from his hand and plunges it into her own chest, telling him, “It doesn’t hurt, Titus.”

DR. EVANS: And she's held up as this great exemplar. Can you imagine living in that kind of society where that's the woman you're meant to aspire to?

Good question, Dr. Evans. There’s also a famous tombstone that describes an ideal woman for us. It says, in sum:

Dr. EVANS: …this is a not beautiful monument, but it's for a beautiful woman, tells you a little bit about her and ends with the famous statement of "she kept her home, she made wool, that's all. Goodbye.” That kinda sums up what a woman should do, apparently. This is a very affectionate tombstone…

Here’s another one from third-century Rome, in which a man named Paternus calls his wife Urbana: “my sweetest, chastest, and rarest wife…she lived every day of her life with me with the greatest kindness and greatest simplicity, both in conjugal love and the industry typical of her character.” I have so many questions: what’s he mean by simplicity? Is he saying they had sweetly boring sex, or what? Either way, what’s being highlighted here is that she wasn’t a complicated woman, or a wild one, and that made her all that much easier to love.

What do these kinds of expectations do to the Roman woman’s psyche? Are these simply the ravings of men that we can roll our eyes at, or are they bars that we feel pressured to rise to? It’s pretty hard to say.