Havens in a Heartless World: Civil War Nurses

season 1, episode 3

Lady nurses were all up in the American Civil War.

But while we might be very familiar with medical practitioners now, they were quite the rare sight back in 19th-century America. Women were often in charge of the medical treatment of their family members, but outside the home medicine was still very much a man's occupation. When the Civil War came, women wanted to use their skills and enthusiasm to take care of the nation's wounded. And there were a whole lot of wounded to care for, in the face of medical knowledge that was not at all prepared for the maladies they would endure.

Women nurses changed the face of Civil War medical care. And in doing so, they experienced things most of them never had before. We're talking cleaning strange men's bodies, aggressive treatments, PTSD, blatant come ons, incoming fire, and a steaming pile of blatant sexism.

Grab some chloroform, some laundry soap, and a pair of rubber gloves.

Let's go traveling.

“If she had requested me to shave them all, or dance a hornpipe on the stove funnel, I should have been less staggered; but to scrub some dozen lords of creation at a moment’s notice was really—really—. However, there was no time for nonsense…I drowned my scruples in my wash-bowl, clutched my soap manfully, and, assuming a business-like air, made a dab at the first dirty specimen I saw…

”

suggested media

PBS's show Mercy Street. Beautifully produced and very well done, this show is based on Alexandria's Mansion House Hospital (a real place) during the Civil War and the many doctors, nurses, and civilians that worked in and around it, from all walks of life. It's a really delightful show, and incredibly well researched. I'm pretty devastated there are only two seasons. If I was a very wealthy woman, I'd fork over a whole lot of it to get this show up and running again.

The National Museum of Civil War Medicine. All you'll ever want to know (and not know) about medicine during the Civil War.

The Clara Barton Missing Soldiers Office Museum. Check out their blog, and you'll find the stories of MANY fascinating ladies, with images and lots of lovely links. A one-stop-shop for lady greatness.

my sources

books

A Diary from Dixie by Mary Boykin Chesnut.

Harriet Tubman: The Road to Freedom by Catherine Clinton, Back Bay Books, 2005.

Historical Encyclopedia of Nursing by Mary Ellen Snodgrass, Diane Publishing Company, 2004.

Living Hell: The Dark Side of the Civil War by Michael C.C. Adams, Johns Hopkins University Press, 2014.

Medicine Women, Curanderas, and Women Doctors by Bobette Perrone, H. Henrietta Stockel, Victoria Krueger. University of Oklahoma Press, 1989.

Personal Memoirs of John H. Brinton: Civil War Surgeon, 1861-1865 by John Hill Brinton.

The Mysterious Private Thompson by Laura Leedy Gansler, retrieved from Archive.org.

The American Civil War: An Anthology of Essential Writing by Ian Frederick Finseth, Routledge, 2006.

This Republic of Suffering: Death and the American Civil War by Drew Gilpin Faust, Vintage Civil War Library, 2009.

online

"The Medical Practitioner Who Paved the Way for Women Doctors in America." Jackie Mansky, Smithsonian.com, November 2017.

"Dec. 14, 1799: The excruciating final hours of President George Washington." Howard Markel, PBS Newshour.

"Ann Bradford Stokes." Robert Slawson, Blackpast.org.

"The Pain of What Might Have Been." Chris Scott, Chapter 16, October 2011.

Joint Committee on the Status of Women. Harvard University.

"Dangerous Liaisons: Working Women and Sexual Justice in the American Civil War." E. Susan Barber and Charles F. Ritter, European Journal of American Studies Special Issue: Women in the USA.

"Ms. Dix Comes to Washington." The New York Times Opinionator blog.

"Diaries of Civil War Women," "Civil War Women Doctors," and "Emma Green." Civil War Women blog.

"5 Pioneering Women Doctors and Nurses of the Civil War." Jocelyn Green's website, 2015.

"The United States Sanitary and Christian Commissions and the Union War Effort." National Museum of the Civil War, May 2017.

"'Senses Were Benumbed:' How a Civil War Nurse Handled Trauma." Melissa DeVelvis, The Clara Barton Museum, March 2018.

"Medical and surgical care during the American Civil War, 1861–1865." Robert F. Reilly, Baylor University Medical Center Journal, April 2016. Retrieved from US National Library of Medicine (NIH).

"Annie Wittenmyer." Sarah Wesson, Richardson-Sloane Special Collections Center, Davenport Library.

"Annie Wittenmyer and Nineteenth-Century Women's Usefulness." Lisa Guinn, Bethany College, State Historical Society of Iowa Volume 74/Number 4, Fall 2015.

"Civil War Nurses." Historynet.

"Love Is a Battlefield: Courtship and Marriage in the Civil War." Tara Laver, LSU Libraries Special Editions, February 2014.

"How Civil War Soldiers Gave Themselves Syphilis While Trying to Avoid Smallpox." Mariana Zapata, Atlas Obscura, 2016.

"Women Prisoners of War in Castle Thunder." Rebecca Beatrice Brooks, August 2012.

"Mary E. Walker." Congressional Medal of Honor Society.

Ladies raised millions of dollars for care of the soldiers at sanitary fairs like this one. And just look at that bonnet!

Courtesy of The Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Division of Art, Prints and Photographs: Print Collection, The New York Public Library. "'The metropolitan sanitary fair.'--Mrs. McClellan's table in the department of arms and trophies--sale of Frank Leslie's sketches" The New York Public Library Digital Collections. 1861 - 1864.

episode transcript

Keep in mind this is a draft: I edit as i record, and throw in all sorts of random funnies.

Before we dive headlong into our new lives as Civil War nurses, let’s talk about where we’re at with medicine in the year 1861. I warn you: you’re not going to like how many years we are away from understanding how disease works.

Mid-century America is just starting to poke its head up out of the ‘heroic’ age of medicine, where we believed that making people better was all about ‘balancing their humors’. The main ways of achieving this aim are explosive and painful: phlebotomy (aka bloodletting); purging (aka inducing vomiting or diarrhea); and giving someone the good old-fashioned sweats. The idea is to let out the bad, restoring the body’s equilibrium. Let’s SHOCK the body back into wellness!

Hey, it worked for ex-president George Washington. After catching a cold via an ill-advised horseback ride through snow, he was freed of several pints of blood, given mercurous chloride, a tartar emetic to make him puke, an enema because...why not, and blistered with cantharidin (the stuff you use to take off warts). And it worked! Oh, wait...he died. Just kidding.

Of course, these treatments are making a lot of people worse.

We’re also operating under the centuries-strong miasmatic theory of disease - the idea that ‘bad air’, or miasma, from decomposing organic matter like sewage is what actually makes us sick. It makes sense, if you think about it. Diseases like malaria are always worst in the South in summer, when it’s hot and sticky, and it seems to move in clouds; it must be the air. People with money leave cities like Washington and New Orleans in the summer for that very reason.

But some people are starting to propose other theories. In 1854 an upstart named, amazingly, John Snow, created an illuminating map that charted an outbreak of cholera in his London neighborhood. He was able to trace the outbreak back to a single water well, suggesting that perhaps the disease was waterborne, not airborne. It was kind of a big deal, this theory. So by the time the Civil War comes around less than a decade later, we understand how disease spreads, right?

Nope. Most people in 1854 just looked at that map and said: YOU KNOW NOTHING, JOHN SNOW!

We won’t really understand how germs work until the 1880s. It will also be a while before we understand that cleanliness isn’t just next to godliness, but also vital when it comes to saving lives. So in the 1860s, surgeons don’t often change the sheets between surgeries - I mean, why bother? - referring with pride to that "good old surgical stink." Joseph Lister will go on to theorize that cleanliness saves lives in hospitals, but not until 1867. Penicillin, saver of many lives, won’t come around until the 1920s. Are we sensing a trend here? In sum, as Civil War nurses, we’re about to see a lot of lives lost that could have been saved had we known a touch more.

On top of that, medical training isn’t what it will be in later centuries. Men only undergo about two years of training, plus some time as an assistant to another doctor, before they’re free to blister and give people enemas. They performed very little surgery, at least before the war.

These trained men were called ‘regulars’. But there are still plenty of ‘irregulars’ out there trying to make a buck with little knowledge or experience, and peddling a whole lot of terrible quackery.

Shall we pause to talk about the treatments you might enjoy from a regular? When our intrepid Union lady spy Elizabeth Van Lew, who we’ll meet properly in another episode, found herself tending to a dying soldier in her home, the doctors she summoned applied the following: cold water anal injections, iodide of potassium, laudanum, and, for good measure, more enemas that involved both egg yolks and turpentine. In the end, the man died...I know. It’s very shocking.

One of the most common medicines is mercury. Unless you’re a woman and suffering from menstrual pains, childbirth problems, headaches, crying, or opinions: then probably it’s laudanum, which is basically opium. There there...that will keep you nice and quiet. At any rate, a lot of it is pretty toxic. In 1860, doctor Oliver Wendell Holmes said this about the contents of America’s medical cabinets:

“I firmly believe that if the whole materia medica, as now used, could be sunk to the bottom of the sea, it would be all the better for mankind—and all the worse for the fishes.”

It makes sense, with all this violent purging and toxic enemas, that homeopathy is becoming popular. Introduced to America in the 1820s, this form of natural medicine had been around for many a century. It posits that ‘like combats like’: a substance that might cause a symptom can, in small doses, be used to treat it. And it seems to work, too, even though our future selves will say it doesn’t. Why? Probably because homeopathists tend to have long consultations with their patients, taking what we now call a holistic approach to medicine. They rely heavily on herbal remedies, good diet, and plenty of rest instead of chemical enemas, thus giving the body a chance to heal itself.

Let’s be clear: men know extremely little about how women’s bodies work. Though they do think that most of your problems emanate from your evil uterus. So women often rely on female midwives during childbirth and their own herbal home remedies to deal with feminine aches and pains, as well as those of the rest of the family. After the Civil War, a gal named Lydia Pinkham will become quite famous for a natural remedy for female pains that you can buy through the mail (you still can buy it in our century). So really, most day-to-day medical care was taken care of at home by women. But as ‘regulars’ became more established, they found ways of elbowing women out of the frame.

Women, of course, have been on the medical scene forever. Take Metrodora, the ancient Greek doctor who was writing about gynecology way back in the 2nd century C.E, or Dorotea Bucca, 14th-century chair of medicine at the University of Bologna. By the time we get to the mid-19th century, women are practicing medicine all over the place, especially out on the frontier. But as irregulars, without a license. Doctoring is in the public sphere, and men don’t think that’s the place for you. So almost all doctors and nurses are men. I say ‘almost’, because there are a few brave ladies who’ve battled their way through.

Take Harriot Keziah Hunt. In the 1830s, after watching doctors treat her very sick sister with blistering and leeches, she turned to homeopathist Elizabeth Mott. She was so impressed by her work that Harriot studied with Elizabeth, eventually opening her own homeopathic practice. She applied to Harvard Medical School in the 1840s, and again in the 1850s, after 15 years of unofficially practicing medicine; the second time, the student body wrote a petition expressing outrage at the prospect of a woman in their midst. “...no woman of true delicacy would be willing in the presence of men to listen to the discussions of the subjects that necessarily come under consideration of the student of medicine,” it said. They “object to having the company of any female forced upon us, who is disposed to unsex herself, and to sacrifice her modesty by appearing with men in the lecture room.”

Harriot wasn’t surprised. But she did say, “The facts are on record - when civilization is further advanced, and the great doctrine of human rights is acknowledged, this act will be recalled, and wondering eyes will stare, and wondering ears will be opened, at the semi-barbarism of the middle of the nineteenth century."

Harvard won’t let a woman study medicine there until the 1940s. But anyway.

Susan Anne Edson was one of the first women to get a medical degree, from Cleveland Homeopathic College in 1854. She will go on to become President James Garfield’s personal physician. But it is Elizabeth Blackwell who’s credited as America’s first female doctor. After being rejected from dozens of premier schools, she got into Geneva Medical College. But only because the faculty let the students vote, and they thought letting her in would be very funny. Susan had to battle from start to finish to be taken seriously. Like when a teacher asked her to leave a lecture on reproduction because he felt it would be too much for her delicate ears. The joke was on them, though: she graduated in 1849 and went on to specialize in gynecology and pediatrics. I’m sure that professor is rolling over in his grave.

When the Civil War comes around, the nation is woefully, tragi-comically unprepared for the carnage. They don’t have many army hospitals, and they don’t yet have a central relief body: Civil War nurse Clara Barton will bring the Red Cross over to America eventually, but she hasn’t done it yet. Before the war, the Union army had 113 doctors. Some of those defected, going South, leaving about 87. Compare that to the number of soldiers Lincoln called up at the beginning of the war: 75,000. That’s one doctor for every 860 Union soldiers. And they only have 20 thermometers to go around.

Given that ratio, you’d think they would be welcoming us lady nurses into the fold with open arms. But hospital nursing is squarely in the public sphere, and thus not everyone is keen to have us. Especially with our annoying habit of getting in the way and trying to change things.

But women nurses aren’t an entirely new concept. Florence Nightingale became quite the sensation in the Crimean War of the 1850s; the ‘lady with the lamp’ who roamed between soldier’s beds through the long nights, effective in her ability to soothe and treat. She paved the way for us Civil War nurses. But in the end, it’s the army’s utter disorganization that will help us burst onto the nursing scene.

From the very beginning of the hostilities, women did what they could to support the war effort. They got together to roll bandages, can food, knit socks, and raise money. The Union government denied that they needed supplies: all is well, ladies, thank you. But the war’s early volunteer nurses knew better. Some soldiers were attacked by a mob in Baltimore, Maryland in April 1861, even before the war’s first big battle, and the injured were taken to Washington to be looked after. The army had nowhere to put them, so they were laid up in places like the Capitol Building. There volunteer nurse Clara Barton found hungry soldiers with no beds, no changes of clothes, and no supplies to tend them with. Afterward, she said:

“Our army cannot afford that our ladies lay down their needles and fold their hands.”

And so they didn’t.

It quickly became clear that the many separate women’s groups needed organizing. So the Women's Central Association of Relief in New York, spearheaded by our lady doctor friend Elizabeth Blackwell and 24-year-old activist Louisa Lee Schuyler, called together a conference to talk about the need for one central body. Some 4,000 women showed up.

Of course, the government wasn’t all that interested in this brilliant idea forwarded by women. So they turned to their male counterparts for help. Once they had some men on board to press their case, old Honest Abe was a little more amenable.

And that is why, when the federal government created the United States Sanitary Commission in June 1861, most of its high-ranking officers were men, while most of its volunteers (you know, the actual workers) were women. Sigh. The United States Christian Commission came later that year. The overarching goal of both of these organizations was to try and improve conditions at field and army hospitals, including in the realm of bad hygiene. A big part of that effort meant sending efficient women out to nurse.

So let’s say we’re Union ladies who’ve asked the Sanitary Commission for a placement. We might first spend some time with Dr. Blackwell and some of her male doctor associates, who are offering a one-month nursing crash course. Yes, you head that right: one month of training, if you get any training at all. Then we’ll be sent to the Commission’s superintendent, the intense and inexhaustible Dorothea Dix. If you’ve watched PBS’s show Mercy Street - if you haven’t, you really must - she’s the one they call Dragon Dix. What they actually call her is “General Dix”...though never to her face.

She was the first woman to serve in a federal-level position, appointed by Lincoln himself in 1861 after much harassing on her part - though, I have to say, he’s lukewarm on the whole lady nurse thing. Like many men of the time, he’s concerned that women don’t have what it takes to be wartime nurses. They would faint, pulling focus and the attention of the doctors. They’d get hysterical every time they saw blood. In the early days, even the Women's Central Association had to admit that “women working in army hospitals are objects of continual evil speaking among coarse subordinates, are looked at with a doubtful eye by all but the most enlightened surgeons, and have a very uncertain, semi-legal position, with poor wages and little sympathy.” To be fair, some nursing women earn a bad opinion. They swoop in of a morning to dab some brows and bring the boys pastries only to end up fainting in the middle of the ward. Though given what we know about Civil War stink, fair enough.

This heavy dose of sexism is there from the beginning, and will continue in some quarters no matter how good you are. Georgianna Woolsey was one of the first women nurses to volunteer in Washington, where she said that surgeons made the lady volunteers scrub floors or assist in amputations to try and horrify them into leaving. When that didn’t work, they tried to force them into unseemly accommodations. If anything, this only made her more determined. When she personally delivered a letter to the White House to ask Abe Lincoln to send some chaplains to the hospital, he did.

Secretary of War Simon Cameron told Dorothea in no uncertain terms that he doesn’t want ladies taking up residence in army camps, and that their applications have to come with excellent references regarding their moral standing. And so General Dix crafted some very intense guidelines for who she would accept into her corps of nurses. Her nurses must be “past 30 years of age, healthy, plain almost to repulsion in dress and devoid of personal attractions.” That means no jewelry, no frills, no fashion: only black and brown dresses will do. Nurses are there to serve, not flirt or distract. If you’re hoping to find yourself a husband amidst those foul-smelling invalids, Ms. Dix would have you go home post haste.

Obviously, she hates the hoop skirt. Those things could knock out a patient or start a fire. But Ms. Dix is not a fan of the bloomer either: you know, the 19th-century version of a full-length skort. She bans them in 1861, but as the war goes on, many nurses are going to wear it anyway. It’s cleaner, and much less likely to get caught in anything disgusting...like weeping sores.

Let’s say we’ve made the cut with Dix. Hooray: we are repugnant! Will we be paid for our work? If we’re with the USCC, then yes. We’ll get a whole $12 a month: that’s equivalent, in today’s money, to $336. A MONTH. But it does include rations, housing, and transportation, so count your blessings. There are many female nurses, particularly in the South, who won’t see any pay at all, particularly those that aren’t attached to an organization. Susie King Taylor followed her husband and the 33rd United States Colored Troops as nurse, teacher and laundress. For several years, this formerly enslaved woman took care of these soldiers, teaching many how to read and write in their down time. She was never paid for her work. Same goes for Anne Bradford Stokes, who was a contraband, or an escaped, African American woman who found her way to freedom and volunteered as a nurse on the Union ship the Red Rover. She later married a man she met on board, and when he died, tried to get a pension based on his service record. It was denied, but she applied again for a pension based on her OWN service. She got it - some 25 years after it was due. Thanks, I guess.

In the South, Confederate women are also stepping up to become nurses. Like Ms. Dix, Southern matrons like Louisa Cheves McCord are not interested in entertaining nurses of fashion. As Southern diarist and very occasional nurse, Mary Boykin Chesnut, said:

“When [McCord] saw them coming in angel sleeves displaying all of their white arms, and in their muslin showing all of their beautiful white shoulders and throats, she felt disposed to order them off the premises. That was no proper costume for a nurse. ”

Mary, it must be admitted, did not always hold up well under the pressure of her nursing visits.

She also recorded a scene she witnessed in Richmond, VA, in which a pretty Southern belle got upset because the men at Miss Sally Tompkins’ hospital wouldn’t stop looking at her. Miss Tompkins suggested she should try and leave her pretty at home. “If you would leave your beauty at the door,” she lamented, “and bring in only your goodness and your energy.”

This may seem harsh, but these women are right to look for no-nonsense nurses. The job you’re about to take up is not for the faint hearted. It’s going to take a lot of energy, a strong stomach, and an indomitable will. You’re almost bound to end up in danger, either from disease or from actual fighting. So why go?

Because women don’t want to sit at home and do nothing. But they also see an opportunity to step out of the private sphere and towards new, exciting horizons. They can’t actually fight (at least not as women), so nursing is as close as they can get. As Louisa May Alcott, author of Little Women and Civil War nurse, put it:

“That way the fighting lies, and I long to follow.”

OK, so it’s your first day: life-saving nurse, reporting for duty! What is it you’re about to encounter? Well...nothing nice, I’ll tell you that. Despite the romantic image of the lady nurse as ‘ministering angel’, your life is going to be gross, tedious, and sometimes horrifying.

From the moment they’re wounded, soldiers are on the clock in terms of chances of survival. First, they sit in the field, then in a makeshift field hospital, and then by train car or wagon to a more established one. The longer that takes, the worse their chances. Even before the soldiers are injured, they’re in a less-than-fresh situation. And because ambulances aren’t amazing in this era, the wounded often sit out in the field and in the sun for hours, spoiling like an overripe peach.

So when a battle happens, you’d better be ready for the stinky flood that’s coming your way. All is chaos and confusion, the wounded lying on every available floor and hall space, all filthy, and all in desperate need of your attention. Often, you’ll be one of the first people to give their ailments any serious attention. Nurse Mary Phinney, stationed at Alexandria’s Mansion House Hospital, said: “Such a sorrowful sight...some of them had been lying three or four days almost without clothing, their wounds never dressed, so dirty and wretched. Someone gave me my charges as to what I was to do; it seemed such a hopeless task to do anything to help them that I wanted to throw myself down and give it up...”

They’re dirty, covered in chiggers and fleas, and don’t really have time to take personal hygiene seriously. Some of them rarely change their underwear or take off their boots….at all.

Clara Barton was horrified when she peeled off one man's socks to find that 'his toes were matted and grown together and are now dropping off at the joint.' TMI, Clara.

And there are surgeons, especially early on in the war, who’ve never amputated anything. Sarah Emma Edmonds, Union nurse and secret lady soldier, compared one surgeon’s work to watching someone tuck into a Thanksgiving turkey. “It was his first attempt at carving, and the way in which he disjointed those limbs I shall never forget.” Watching incompetent doctors, made callous by the sheer number of patients they have to get through, is going to seriously try your patience. While helping with an amputation, Louisa May Alcott was less than impressed with a surgeon’s bedside manner. When he commanded her to hold the patient down, she “…obeyed, cherishing the while a strong desire to insinuate a few of his own disagreeable knives and scissors into him, and see how he liked it.”

Poor Richard D. Dunphy. He served aboard the USS Hartford and was wounded in the Battle of Mobile Bay. At least he was awarded the Congressional Medal of Honor. That's kind of cool.

Richard D. Dunphy, formerly Coal Heaver of U.S. Navy in uniform] / S. Masury, photographic artist, 289 Washington St., Boston. Courtesy of the Library of Congress.

To be fair, these surgeons were often working on days without sleep, very few supplies, and a constant sea of patients. He has to try and fix them up as fast as he can. So as nurse, will you be asked to take up a bone saw? Of course not: ladies aren’t surgeons, dammit. BUT WAIT! One of them is!

Dr. Mary E. Walker was an assistant surgeon for the Union army. A graduate of Syracuse Medical College, and the second woman in America to get a medical degree, she volunteered her services at the U.S. Patent Office. She was rejected when she applied for an official position in the army, but in 1862 she went to Virginia anyway wearing men’s pants, boots, cloak, and broad-brimmed beaver hat. At Fredericksburg, she gave orders so loudly and with such confidence that the guys around her just did what she said. But she got a lot of flak from the doctors: they refused to work with her, and they spread rumors that she was - you guessed it - a HARLOT. By the time she was officially appointed assistant surgeon in 1864, she’d seen her fair share of bone saw action. She also crossed over the lines between armies to tend to women needing a midwife, helping soldiers and civilians suffering from typhoid and, you know, doing a touch of spying here and there.

But twice as many patients are dying of disease than battle wounds. There were some 75,000 cases of typhoid fever in the Union army alone. Things like dysentery, pneumonia, mumps, measles and tuberculosis spread like wildfire through dirty hospitals with understocked medical cabinets and undernourished bodies. And disease can strike down anyone, from the lowliest recruit to a top-ranking commander, particularly in the swampy South. “There is hopeless desperation when one is engaged in a contest with disease…” one officer, stationed in the South, said. “The evening dews fall only to rise again with fever in their breath.”

Doctors are forever running out of medicine, especially when the enemy messes with railroad supply lines, so about two-thirds of the medicine used in the war is botanical. Harriet Tubman, Underground Railroad conductor and all-around badass, who we’ll talk about more later, used her knowledge of local plants to tend to the ever-growing number of sick. She did so well with her ministrations that she was called to a Union outpost in Florida, where many men were dying of dysentery, and nursed both contrabands (escaped enslaved people) and soldiers. Somehow, she managed not to get sick herself. Which is pretty incredible.

You’re spending a lot of time with very sick people, and probably working long hours without enough food or rest. You’ll be tempted to keep going through night and day, as the flow of needy soldiers is never ending. But nurse Emily Parsons knew how important it was that she rest, no matter how many soldiers there were to tend to: “...now if I get my strength back, I shall keep where I can use it, and not, by getting sick, become of no use or comfort to anybody. We must have our bodies in good order, if we want to do for others.”

Confederate nurse Carrie Cutter was the first girl to become a nurse for the south, serving alongside her surgeon father. She died, age 18, of typhoid fever. Disease is what ended Louisa May Alcott’s nursing career: she got so sick that her father had to come and get her. This is truly the biggest enemy you’ll face.

It’s worth noting, too, that women nurses aren’t just tending to soldiers in hospitals. They’re going to horrifically terrible army prisons, offering aid and comfort to the soldiers rotting away in there. Sometimes they even tend to enemy soldiers, which obviously causes much consternation. When Union lady spy Elizabeth Van Lew and her mother went to tend to Union soldiers in Richmond, the hotbed of the Confederacy, the press had an absolute field day. “These two women have been expending their opulent means in aiding and giving comfort to the miscreants who have invaded our sacred soil, bent on raping and murder, the desolation of our homes and sacred places, and the ruin and dishonor of our families.” But women can get away with it because, in large part, of their role as society’s pillars of humanity. ‘It’s the Christian thing to do!’ They cry. And thus they help save and comfort many soldiers on both sides of the line.

Almost inevitably, you’re going to find yourself woefully short on supplies of all kinds. Dix-approved nurse Lucy L. Campbell Kaiser complained:

“The fact was I could not get enough food: butter out, sugar out, no crackers, poor bread, tough beef. No vegetables, no candles; in fact, the commissary was bare, and the officers in town on a drunk. ”

And this is where aid societies like the USSC come in, supplying everything from bandages and medicines to canned fruit and candy. Here’s a mere sampling of what the Women’s Central Association of Relief was able to collect and distribute from 1861 to 1863: 91,000 socks; 28,000 pillowcases; 4.5 thousand pounds of pickles; more than 16,000 jars of jelly. But some lady nurses found ingenious ways to get supplies to their boys quickly. They held huge fundraising fairs and bazaars: at one of the biggest, Abe Lincoln put up 10 signed copies of the Emancipation Proclamation for sale at $10 a pop. These fairs raised millions of dollars for soldier care and aid. But individual women also found ingenious ways to collect supplies. Mary Ann Bickerdyke, a nursing dynamo we’ll hear more about later, found every opportunity to collect supplies from other ladies. At a speaking engagement at a church, while explaining how she bound up amputee stumps when she ran out of bandages, she told the audience members to stand up and drop a petticoat. She then collected them, filling up three trunks, and took them to Andersonville prison to bind up wounds with.

You’ll have to improvise, learning quickly from experience. Like Katharine Wormely, who tied flasks of brandy and broth over her shoulders with ribbon so that her hands would always be free. And you’ll need your hands free, because you will be stepping in to help overtired and overworked surgeons. Hannah Ropes, who supervised Louisa May Alcott and would, sadly, lose her life to typhoid fever, said that her acting surgeon spent most of his day completely drunk. Women nurses step in to dress wounds, splint bones, and staunch bleeding. And they often do it with a gentler touch.

With so much disorganization and chaos, there’s a lot of room for women nurses and matrons to take the initiative, particularly when it comes to proper nutrition. In 1863, the Senate refused to spend more than 10 cents a day on food for a wounded soldier, and the House put down a bill to provide any trained cooks. There were points at which wounded soldiers were quite literally starving. But Emily Mason, the superintendent at a Richmond hospital, was damned if she wouldn’t scare up a Christmas meal for her soldiers: she found a way to supply 15 turkeys, 150 chickens and ducks, oysters, custard, pudding, and more.

The issue isn’t just that there isn’t enough food. It’s that most of it is fatty dried meat and hard tack, and much of it is spoiled. Soldiers are suffering almost constantly from serious gastrointestinal wobblies - we’re talking some 711 cases per every 1,000 soldiers, and there is no Pepto Bismol to soothe it. Annie Wittenmyer was horrified when she found her brother David, sick with dysentery and typhoid, with only rotten food to get by on. She asked the U.S. Christian Commission to give her the funds to set up special diet kitchens. These were revolutionary: special meals were made for specific patients with the aim of trying to heal him through nutrition...a very novel idea. Annie set up several of them, all run by women superintendents. She even published a recipe book with the Christian Commission, filled with the kinds of recipes that the wounded could eat.

Despite this innovation, Annie was continually battling haters accusing her of fund and supply mismanagement. It didn’t help that by 1862, this single mother was making $100 a month for her war work: a huge sum for a woman, and enough to make her the subject of suspicion and wrath. A convention held in Iowa in 1863 that was supposed to be about organization and funds ended up being an unofficial trial for Annie. They accused her of a range of things, including, OF COURSE, accusations of harlotry. The list of accusations included “...waste of goods, embezzlement of stores, & reveling & carousing with the officers & drinking the wines & eating the delicacies” entrusted to her care. It got so bad she had to resign.

Whatever supplies you have, you’ll have to guard them: people will steal them if they get a chance. Mother Bickerdyke was particularly annoyed when she suspected that hospital workers were filching food she’d set aside for the wounded. She stewed some peaches, laced with some kind of purgative, and left them out to cool while she went about her business. Soon enough, she heard unhappy calls from the kitchen, but she was unrepentant: she told them next time they stole some of her peaches they might find themselves with a belly full of rat poison. Are you in love with Mary yet? I am.

Armed with turkeys and stewed peaches or not, there will be times when you have to watch a lot of suffering, and won’t be able to do ANYTHING to stop it. But your job isn’t just to tend to a soldier’s physical needs. There are his social and psychological needs, as well.

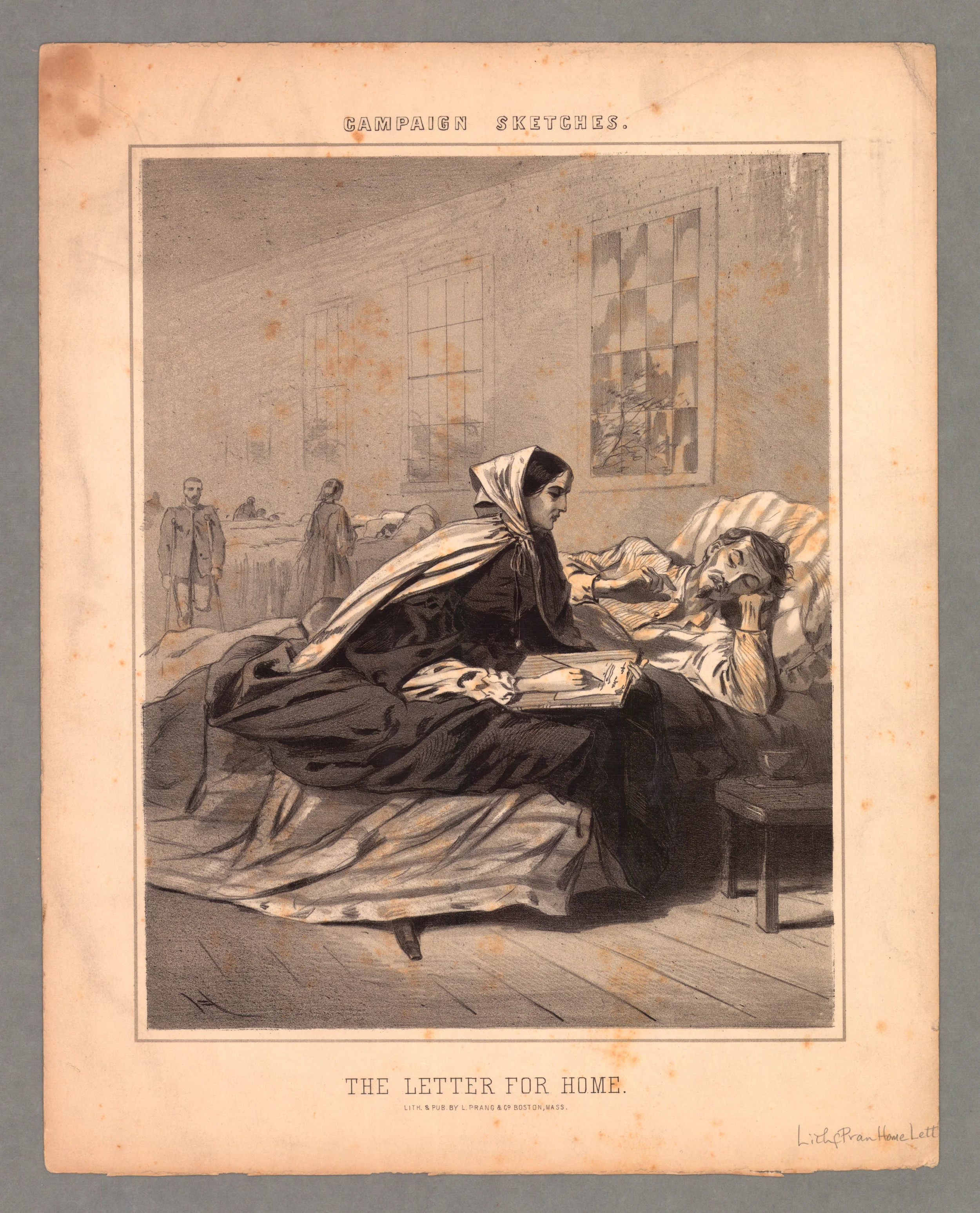

Most soldiers have never been this far away from home, and have never, ever known a life without the attentions of a mother, a wife, a sister, or some other female family member. Before the war, the vast majority of people died at home. Hospitals are only for the indigent or hapless. Women are an important part of the notion of the Good Death: a way of dying Victorian society holds very dear. Usually, this ritual involves being in bed surrounded by loved ones, to whom you make your last confessions and explain your willingness to go to God. Last words are hugely important in this era: if your loved ones don’t hear them, they won’t know whether or not they will see you in heaven. To die far from home, without this ritual, is a horrifying prospect, and these soldiers are very scared of it. Helping with this ritual is something only a female nurse can truly do.

So they’ll often ask you to write letters home for them, composing some last words that you think their female family members might appreciate. You might wash their bodies, as their relatives would, and get them ready for a proper burial or to be shipped home. In dire circumstances, you might even stand in as substitute kin.

Clara Barton was called to the bedside of a boy who was dying and calling out for his sister Mary. In his delirium, he thought she was Mary and though she couldn’t quite bring herself to call him ‘brother’, she did pretend so as to bring him some comfort. You’ll probably have to deal with what they call ‘soldier’s heart’ - what we, in our century, might call PTSD. One night, Louisa May Alcott found herself alone in a ward after a recent battle, next to a man who spent his night reliving it. He cheered or cried out to friends who’s fallen, ducked incoming shots - he even tried to pull Louisa away from imaginary bursting shells. Meanwhile, another one kept shambling through the ward and crashing into beds, telling her that he was dancing his way home. Things got so bad that the 12 year old drummer boy burst into tears in the corner, weeping for the man who’d died saving his life. There is no worse night for a nurse.

There’s a popular Civil War song that captures this scene exactly. It’s called “Be My Mother Till I Die”:

Let me kiss him for his mother,

or perchance a sister dear:

Farewell, dear stranger brother,

Our requiem, our tears.

Many nurses are looking after soldiers who are emotionally shattered: having nightmares and hallucinations, crying out for people that aren’t there. You look at these poor, wounded soldiers almost like your children, and they’re looking to you to provide the comforts they’ve been denied. At least 10% of women nurses will break down under the emotional strain of those burdens. With such heavy baggage to bear, you’ll have to find time to hunker down now and then and have a cry. Or you’ll find a way to numb out completely. As Amanda Akin wrote to her sister, “It seemed to me...that I had forgotten how to feel...it seemed as if I were entirely separated from the world I had left behind.” Amanda wasn’t the only one. Young Cornelia Hancock felt increasingly numbed by her experiences of horror, and more and more detached from the life she’d left behind at home. After the battle of Gettysburg, she wrote home that “I could stand by and see a man’s head taken off” and not feel much of anything at all.

And then, of course, nursing comes with many difficult and emotional decisions. What about when you find an enemy soldier under your care? What do you do then? We haven’t yet seen the Geneva Convention, which will dictate that wounded soldiers should be cared for no matter what their politics are. For nurses like Clara Barton, this idea seemed clear and simple enough. For others, it’s harder. Confederate nurse Kate Cumming said of dealing with some wounded Yankees:

“Before I went in, I thought I would be polite... but when I saw them laughing and apparently indifferent to the woe which they had been instrumental in bringing upon us, I could not help being indignant. [But] seeing an enemy wounded and helpless is a different thing from seeing him in health and power.”

Tending to soldiers from both sides of the line does allow some specific advantages. Some women are able to move back and forth across the lines in this way, like our beaver hat wearing friend Dr. Mary Walker. That’s also how Mary Kate Patterson Davies smuggled medicine to Confederates under her hoop skirt, and Virginia Bethel Moon snuck away with opiates in her parasol.

One of the things that makes women crucial to the nursing effort is how so many of them roll up their sleeves and say: “this place is gross. I’ll go get the mop.” The doctors are so busy chopping off limbs and being important that they don’t often have time for housekeeping. Which is more important, saving a young man from gangrene or scrubbing a floor? I ask you. But as keepers of the home and guardians of the family’s health, women understand that cleanliness matters. And if there’s one thing we know how to do in this era, ladies, it’s clean!

Sally Louisa Tompkins converted her Richmond home into a 22-bed hospital early on in the war. Though she couldn’t offer any real medical training, she did offer soldiers a well-kept place to rest: her main ingredients for success were clean air, light, whiskey and prayers. This treatment seemed to work: of 1,333 patients under her care, she had only 73 of them die: a much better batting average than others. Jefferson Davis, Confederate President, made her a captain in the cavalry, making her one of the only, if not THE only, official female officer.

Before long, you might get sick of being stuck in a hospital far from where the action is.

Harriet Eaton from Maine certainly did. “I am more than ever dissatisfied with this way of working. I reach the suffering and destitute so indirectly. I don't want to sit here and do the polite for a mess table, but would much prefer to live on hard tack and a cup of tea untrammeled.”

Most nurses, especially those working for organizations like the Sanitary Commission, stayed in hospitals well behind the front lines. But women like Clara Barton saw that there was a clear need for help and supplies up at the front, at field hospitals close to the actual fighting, but also at the battle as it was happening. It’s one thing to dab brows and read the Bible aloud in a proper hospital. To go out to the field...oh my. Prostitute central. Most of the men in charge out in the field do NOT want you there. I can’t stress enough how unseemly they think this is. But women like Clara Barton and Mary Anne Bickerdyke saw clearly how many men lost their lives because of how long it took them to get to hospitals. They needed more help at the front, and they were determined to give it.

Field hospitals are makeshift, intense, crowded, and dangerous. Let’s have our poet friend Walt Whitman describe the scene at the battle of Fredericksburg. “Outdoors, at the foot of a tree, within ten yards of the front of the house, I notice a heap of amputated feet, legs, arms, hands, and a full load for a one-horse cart”. He said the makeshift hospital was “quite crowded, upstairs and down, everything impromptu, no system, all bad enough, but I have no doubt the best that can be done; all the wounds pretty bad, some frightful, the men in their old clothes, unclean and bloody.” Cornelia Hancock had this to say about battlefield perfume: “A sickening, overpowering, awful stench announced the presence of the unburied dead ...at every step the air grew heavier and fouler until it seemed to possess a palpable horrible density that could be seen and felt and cut with a knife …”

Nursing at the front isn’t going to be pretty. You’re bound to see some fighting, and it’s going to be a hard sight to forget. Sarah Emma Edmonds, lady soldier, nurse AND spy, saw the devastation at many a battlefield. “Men tossing their arms wildly calling for help; there they lie bleeding, torn and mangled; legs, arms and bodies are crushed and broken as if smitten by thunderbolts; the ground is crimson with blood.” Cornelia Hancock was there through the Battle of Gettysburg, where she was often the only women around. “There are no words in the English language to express the suffering I witnessed today,” she said:

“ ...I gave to every man that had a leg or arm off a gill of wine, to every wounded in Third Division, one glass of lemonade, some bread and preserves and tobacco...I would get on first rate if they would not ask me to write to their wives; that I cannot do without crying.”

These places are gross and upsetting, but also dangerous. There is no guarantee that a stray bullet won’t find its way into a hospital camp. But some woman decided to go anyway, because they thought they could be of the most service out where the action was actually happening. Clara Barton never nursed for a particular agency: she would just collect supplies and head out to the front to distribute them. Eventually, she took wagon loads of supplies and some women helpers out to the battlefield. A handful of women, a wagon, and 3,000 soldiers: now that’s some pretty daunting math.

Often the Army’s medical supplies are held back until the battle is over to ensure they aren’t taken by the enemy. That means when Clara Barton arrived on the scene at Antietam, she often found doctors who’d run out of everything. When she arrived at Antietam, the war’s bloodiest battle, they had no chloroform, no bandages, no liquor: nothing. They were wrapping up wounds with corn leaves.

Unsurprisingly, the soldiers LOVE lady nurses at the battlefields. Many, when they see you coming, will weep. Lizzie from Illinois was affectionately nicknamed ‘Aunt Lizzie’ and given credit by the surgeon she supported for saving hundreds of lives. Arabella Barlow was at the battles of Antietam and Gettysburg, where she dashed across the lines several times while being shot at to attend to the wounded. Inventor of the special diet kitchen, Annie Wittenmeyer, dodged bullets and shells to distribute supplies. For that, big deal Union General Ulysses S. Grant said that “No soldier on the firing line gave more heroic service than she rendered.”

Mother Bickerdyke was a particularly effective and hardcore field nurse. When she marched herself over to a field hospital in Cairo, Illinois, armed with nothing but a wicker basket full of foodstuffs to offer relief aid, she found three tents in a muddy field, sweaty patients lying on dirty straw, and barely any edible food. She personally stripped every patient, washed them with hot water and brown laundry soap, then shaved them to get rid of lice. She got them fresh linens and bribed people nearby for better food. She also did a LOT of laundry: she washed almost 4,000 pieces of clothing, rinsed them in a stream, and dried them out on branches in the woods nearby. In ONE DAY.

Using a woodstove, she made cookies and home remedies; she taught cooks in the field, often men who don’t know what they’re doing, how to make the most of limited rations. She handed out panada, a gruel of brown sugar and bits of hardtack stirred into whiskey and hot water. All without pay, of course. She moved where the army did, prowling battlefields at night to try and find wounded soldiers. She served in 19 battles, often under active fire. Whew.

Much like Clara, Mother Bickerdyke was not always beloved by surgeons. When she dobbed in one for wrongdoing, General Ulysses S. Grant responded:

“My God, man, Mother Bickerdyke outranks everybody, even Lincoln. If you have run amok of her, I advise you to get out quickly before she has you under arrest.”

If you think that men are confused by your presence in hospitals, things get even more confused out on the battlefield. The women who follow the army around fall into certain categories: Camp followers are often soldier’s family members, there to help with laundry and cooking. Others are peddlers; others are harlots; still others are spies. So nurses who spend time around military camps have to deal with people accusing them of being all of these.

African American lady nurses - much like black soldiers and civilians - suffer under these charged conditions more than anyone. In the South, enslaved women are sometimes forced to nurse Confederate wounded and wash their clothes. When black men were finally allowed to enlist in the Union army, they often didn’t get the support they needed, and so many black women stepped up to try and help. Activist and writer Sojourner Truth collected food and supplies specifically for under-served black regiments, then moved to Washington in 1863 so she could nurse them and help teach freed slaves. Charlotte Forten Grimke went down South to teach freed people in the Sea Islands, where Harriet Tubman did her nursing. She became friends with Robert Gould Shaw, the leader of the all-black 54th Massachusetts Regiment, and was there when they stormed Fort Wagner - a very bloody business. Shaw was killed, but she volunteered to nurse the surviving soldiers back to health.

Even if you aren’t nursing up at the front, hospital life doesn't guarantee you won’t see military action. If the enemy draws near, you’ll need to evacuate. That's what Emily Mason did during the burning of Richmond in 1865: “We led the way through the fire and smoke, our sleeves singed and our faces begrimed with sweat and dirt. My driver had become so unaccountably drunk that I could hardly hold him upon his seat.”

And then, there’s the risk that you might be thrown in jail. Our surgeon friend Mary E. Walker was caught by Confederates in Georgia, mid-amputation, wearing her delightfully conspicuous fancy man outfit, and arrested under suspicion of being a Union spy. The Richmond press had this to say about her: “She was consigned to the female ward of Castle Thunder, there being no accommodations at the Libby for prisoners of her sex. We must not omit to add that she is ugly and skinny, and apparently above thirty years of age.” She spent a horrible six months at Castle Thunder, which was dirty, disease ridden, with few supplies and harsh treatment. Mary had to deal with bugs, rats, rumors that she slept with guards, and a guard shooting at her through her doorway. When questioned about her sex by reporters, she said:

“I am a lady, gentlemen, and I dare any man to insult me.”

She stroked a small knife in her lap for emphasis. It’s worth noting, too, the following nugget: she was awarded the Congressional Medal of Honor for her service, and it was then TAKEN AWAY FROM HER in 1917. Don’t worry: she refused to give it back. And it was restored years later, in 1977. She’s the only woman who has been given that honor as of 2018.

Alright. So are we tired of dressing festering sores? Well, good: the war is ending: whew! We made it. So what effect has this experience had on us? How might this change out lot in this world?

We’ve had - and will continue to have - a huge impact on the lives of soldiers and their families. Women nurses stay very busy helping soldiers and their families: setting up orphanages for veterans’ children; raising money for everything from spousal support for widowed wives of soldiers to providing amputees with prosthetic legs. Clara Barton spent years locating thousands of missing soldiers. As head of the Missing Soldiers Office, she was able to locate around 22,000 men: some of them still alive, after all. Many women opened up schools in the North and South to support and educate newly liberated people. Our swearing, horse riding nurse friend Cornelia Hancock helped found such a school in South Carolina, where she taught for a decade.

They will go on to create organizations like the Women’s Christian Temperance Union, the Women’s Educational and Industrial Union, and the American Red Cross. They create welfare programs for veterans, fallen women, widows. But very few of them will continue working as nurses. Still, their wartime work has paved the way for things to come. In 1868, the American Medical Association will say that they think there should be some schools opened up to train nurses. By 1880, there will be 15 of them; by 1900, 432. These schools open up a whole new and respectable profession for women; a way to make a living and serve the greater good.

More than that, their experiences in the war gave women industry and self-confidence. They’d experienced the world in a new way - one there was no forgetting. As diarist Lucy Buck said, “We shall never any of us be the same as we have been.” And that was true for women. They could go out into the world and do things. It was this spirit, and this realization, that helped fan the flames of the women’s rights movement and pushed ladies to venture into all new territory.

Until next time.

Voices

John Armstrong = Oliver Wendell Holmes

Phil Chevalier = Richmond newspaper

Steven Reichel = disgruntled medical students

Edie Chevalier = Dorothea Dix

Joan Chevalier = Harriot Keziah Hunt

Louisa Matthew = Mary E. Walker

Andrew Goldman = Ulysses S. Grant

Billy Kaplan = Walt Whitman

Claire Burke = Sarah Emma Edmonds

Kath Brandwood = Louisa May Alcott

Nancy Wassner = Clara Barton

Melissa Fisanich = Mary Phinney

Beth Ferracone = Cornelia Hancock

All others by Kate Armstrong (aka me)

Music

All of the royalty-free music featured in this episode comes from Audioblocks.